Reporting on Juvenile Crime: Balancing Privacy, Defamation, and Juvenile Law Article 61 (Japan Supreme Court, 2003)

Introduction

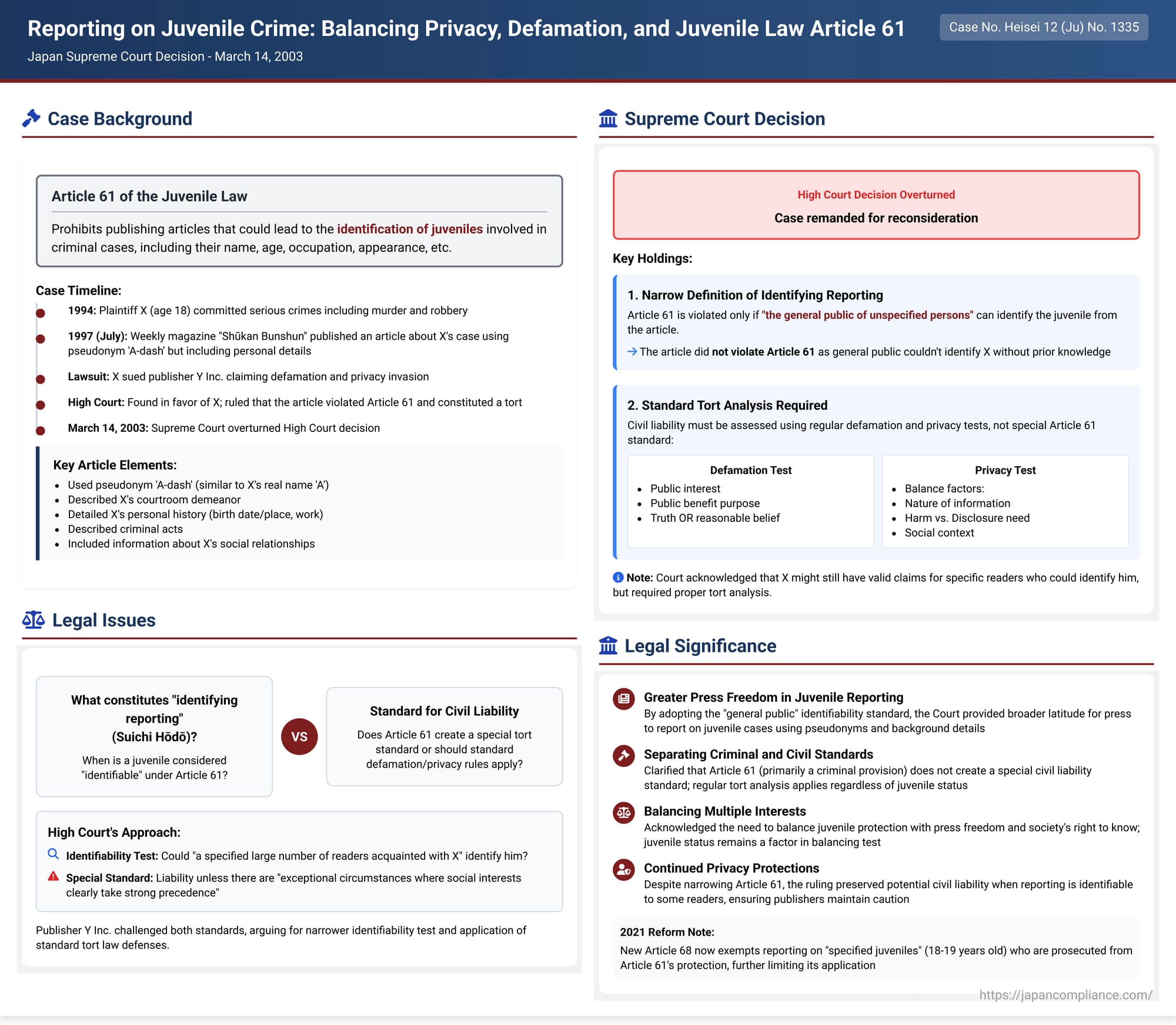

On March 14, 2003, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan rendered a significant judgment in Case No. Heisei 12 (Ju) No. 1335, a civil damages lawsuit involving the publication of an article concerning a former juvenile offender. The plaintiff, anonymized as X, who had committed serious crimes as a juvenile, sued the publisher of a prominent weekly magazine ("Shūkan Bunshun," published by Y Inc.), alleging defamation and invasion of privacy. The case required the Supreme Court to address the complex interplay between freedom of the press, the protection of individual reputation and privacy, and the specific prohibition found in Japan's Juvenile Law Article 61 against media reporting that could lead to the identification of a juvenile involved in a case.

The Supreme Court's decision clarified two crucial points: first, it established a specific standard for determining what constitutes prohibited "identifying reporting" (suichi hōdō) under Article 61; second, it mandated that even when reporting involves juvenile offenders (or former juvenile offenders), civil liability for defamation or privacy invasion must be assessed using standard tort law principles and justification tests, rather than a unique standard derived solely from the Juvenile Law. The judgment overturned a lower court decision that had found the publisher liable based on a broader interpretation of Article 61.

Background: Juvenile Law Article 61 and Media Reporting

Japan's Juvenile Law aims to promote the sound upbringing of juveniles, emphasizing rehabilitation and protection over punishment. A key provision reflecting this philosophy is Article 61, which prohibits publishing articles or photographs in newspapers or other publications that state the name, age, occupation, residence, appearance, etc., of a juvenile referred to the Family Court or a juvenile prosecuted for a crime, if these details would allow the inference that the individual is the juvenile involved in the specific case. This prohibition on identifying reporting (suichi hōdō) aims to:

- Protect Juveniles from Stigma: Prevent the lifelong labeling and social ostracization that can result from public identification with a crime committed during youth.

- Facilitate Rehabilitation and Reintegration: Allow juveniles a better chance to reintegrate into society without the constant burden of past offenses being known publicly.

- Protect Developing Rights (Potential View): Some interpretations also link Article 61 to a broader concept of protecting the juvenile's right to healthy growth and development, arguing that public exposure can be particularly damaging during formative years.

This protection contrasts with the generally broader scope allowed for reporting on crimes committed by adults, where public interest and the right to know often weigh more heavily against individual privacy concerns. However, the precise scope and legal effect of Article 61, particularly its interaction with civil liability for defamation and invasion of privacy, had been subject to debate.

Facts of the Case

- Plaintiff X: Born in October 1975. In September-October 1994 (when X was 18 years old), X committed a series of extremely serious crimes, including murder and robbery resulting in death, in conspiracy with adults and other juveniles. X was subsequently prosecuted and stood trial in the Nagoya District Court.

- Defendant Y Inc.: A publishing company responsible for the weekly magazine "Shūkan Bunshun."

- The Article: On July 31, 1997, while X's criminal trial was still pending but after X had turned 21 (and thus was legally an adult), Y Inc. published an article in "Shūkan Bunshun." The article bore titles such as "'Juvenile Offender' Cruelty" and "Exclusive Release of Courtroom Notes." It primarily focused on the feelings of the victims' parents and included observations from the courtroom proceedings.

- Reference to X: The article referred to Plaintiff X using a pseudonym, 'A-dash'. However, it also included numerous details about X, such as:

- Observations of X's demeanor in court.

- Descriptions of parts of the criminal acts.

- X's personal history (including birth date/place, delinquency record, work history).

- Information about X's social relationships.

- The Lawsuit: X sued Y Inc., claiming the article defamed him and invaded his privacy, seeking monetary damages based on tort law (Civil Code Article 709).

The High Court's Decision

The Nagoya High Court found partially in favor of Plaintiff X, holding Y Inc. liable for damages. Its reasoning included several key points:

- Identifiability: The High Court concluded that X could be identified from the article. It found the pseudonym 'A-dash' was similar to X's actual name at the time ('A'). More importantly, the detailed personal and background information provided matched X's history so closely that "a specified large number of readers acquainted with [X]" and "an unspecified large number of readers in the community where [X] had his base of life" could easily infer that 'A-dash' referred to X.

- Violation of Juvenile Law Article 61: The High Court interpreted Article 61 broadly, stating its purpose was to protect not only a juvenile's right to healthy development but also their honor and privacy. It ruled that publishing identifying information in violation of this article constitutes a human rights violation and gives rise to tort liability.

- Special Standard for Justification: Crucially, the High Court held that the standard defenses applicable in adult defamation cases (truth, public interest, public benefit) do not automatically excuse a violation of Article 61. It proposed a stricter standard: liability for violating Article 61 could only be avoided if there were "exceptional circumstances where the need to advocate for social interests clearly takes strong precedence over the rights or legal interests of the juvenile that should be protected."

- Application to the Case: The High Court deemed the article to be prohibited identifying reporting (suichi hōdō) under its interpretation of Article 61. Finding no such "exceptional circumstances" to justify the publication, it concluded that Y Inc. was liable in tort.

Y Inc. appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's 2003 Decision and Reasoning

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's finding of liability against Y Inc. and remanded the case back to the High Court for reconsideration. While acknowledging the article could potentially constitute defamation and privacy invasion for certain readers, the Supreme Court found fundamental errors in the High Court's legal analysis, particularly concerning Article 61.

- Defining Suichi Hōdō (Violation of Article 61): The Supreme Court explicitly rejected the High Court's standard for identifying reporting. It established a narrower test:

- The Standard: Whether reporting violates Article 61 depends on whether "the general public of unspecified persons" (futokutei tasū no ippanjin) can infer from the article that the individual mentioned is the juvenile involved in the specific case.

- Application: The Court found that while Y Inc.'s article used a similar pseudonym and provided background details, it lacked information sufficient to specifically identify X (like a full name or photograph). Therefore, the general public, those without prior acquaintance or specific knowledge of X, could not reasonably infer his identity from the article alone.

- Conclusion on Art. 61: Consequently, the Supreme Court held that the article did not violate Juvenile Law Article 61.

- Potential Liability Despite No Art. 61 Violation: Importantly, the Supreme Court clarified that the finding of no Art. 61 violation did not automatically absolve Y Inc. of all potential liability.

- The Court acknowledged that the information published (details of heinous crimes, personal history) was indeed potentially defamatory and private.

- It also acknowledged the possibility that some readers – specifically those acquainted with X or possessing prior knowledge of his background or the crime details – could potentially identify him from the combination of the pseudonym and the specific details provided.

- Therefore, the publication could still constitute defamation and/or invasion of privacy towards those readers who could make the identification, even if it wasn't suichi hōdō violating Article 61 in the strict sense (i.e., identifiable by the general public).

- Error in Liability Analysis (Justification Standards): The Supreme Court identified the High Court's primary error as its failure to apply the correct legal standards for determining whether tort liability arose from the potential defamation and privacy invasion.

- The High Court had wrongly presumed an Article 61 violation and then applied a special, heightened justification standard ("clearly outweighing social interest").

- The Supreme Court mandated that liability must be assessed separately for defamation and invasion of privacy, using the well-established tests for each:

- Defamation Test: Liability is precluded if (a) the statements concern matters of public interest, (b) the publication's main purpose is to serve the public benefit, AND (c) the facts stated are proven true in essential aspects, OR, if not proven true, the publisher had reasonable grounds to believe they were true (citing 1966 precedent).

- Privacy Invasion Test: Liability arises only if the individual's legal interest in not having the private facts disclosed prevails over the reasons for disclosure. This requires a comparative balancing of various factors: the plaintiff's age and status at publication, the nature of the private information, the scope of dissemination and potential harm, the purpose and significance of the publication, the social context, the necessity of publishing the specific private details, etc. (citing 1994 precedent).

- Remand: Because the High Court had skipped these necessary, specific analyses by relying on its incorrect Art. 61 finding and applying the wrong justification standard, the Supreme Court found its decision resulted from insufficient deliberation (shinri fujin) and constituted a legal error requiring remand for proper consideration under the standard tort law frameworks.

Discussion: Implications of the Ruling

The 2003 Supreme Court decision significantly impacted the legal landscape surrounding media reporting on juvenile crime in Japan:

- Narrowing Article 61's Scope: By defining suichi hōdō based on identifiability by the "general public," the ruling considerably narrowed the practical scope of Article 61's prohibition. It essentially means that unless a report uses a juvenile's real name, photograph, or other directly identifying information readily understandable by anyone, it is unlikely to violate Article 61. This offers greater clarity and protection for media outlets reporting on sensitive cases, allowing them to publish significant details (using pseudonyms) without necessarily falling afoul of the Juvenile Law itself.

- Debate on Protection Level: This narrow standard sparked debate. Critics argued it insufficiently protects juveniles, particularly their ability to reintegrate into their home communities, where acquaintances can often piece together identities from detailed reports even with pseudonyms. They contended the High Court's broader standard (identifiability by community/acquaintances) better served the rehabilitative goals of the Juvenile Law and potential "developmental rights." Proponents of the Supreme Court's standard countered that it appropriately balances press freedom with juvenile protection, arguing that Article 61's core purpose is to prevent widespread, national stigmatization by the general public, not necessarily shield individuals from recognition by those who already know them. Preventing identification by the general public is seen as crucial for allowing a fresh start elsewhere if needed.

- Separate Analysis Remains Crucial: The judgment strongly reaffirms that Article 61 does not create an independent tort or replace standard tort law analysis. Even if a publication avoids violating Article 61 (due to the narrow "general public" test), publishers remain vulnerable to defamation and privacy invasion claims if the content is harmful and identifiable to some segment of the readership. Publishers must still carefully consider the standard justification defenses for both torts.

- Role of Article 61 in Balancing: While not a direct source of liability or a unique justification standard, the spirit of Article 61 – the societal emphasis on protecting juvenile rehabilitation – could still be a relevant factor considered within the balancing test used for privacy invasion claims. The fact that information relates to acts committed as a juvenile might weigh in favor of non-disclosure when balanced against the reasons for publication.

- Impact of 2021 Juvenile Law Reform (Article 68): It's crucial to note that legislative changes in 2021 introduced Article 68 to the Juvenile Law. This new provision explicitly exempts reporting on "specified juveniles" (those aged 18 or 19 at the time of the offense) from the prohibition in Article 61 if they have been prosecuted. This means that for individuals like X in this case (who committed offenses at 18 and was prosecuted), Article 61 would no longer apply today. The rationale reflects a societal shift towards treating 18 and 19-year-olds prosecuted in open court more like adults regarding public identification. This reform significantly limits the applicability of the Article 61 debate laid out in the 2003 judgment to the 18-19 age group in similar circumstances.

Conclusion

The 2003 Supreme Court decision remains a landmark ruling in Japan concerning media reporting on juvenile offenders. It established a narrow, "general public" standard for identifying prohibited reporting under Juvenile Law Article 61, offering greater leeway to the press compared to the lower court's interpretation. Simultaneously, it firmly separated Article 61 analysis from standard tort law, requiring courts to apply the established justification tests for defamation and invasion of privacy independently, even when the subject matter involves juvenile crime. While the practical impact concerning 18 and 19-year-olds has been altered by subsequent legislation, the case provides critical insights into the judicial balancing act between protecting vulnerable youth, upholding freedom of the press, and ensuring accountability for harmful publications under Japanese civil law.