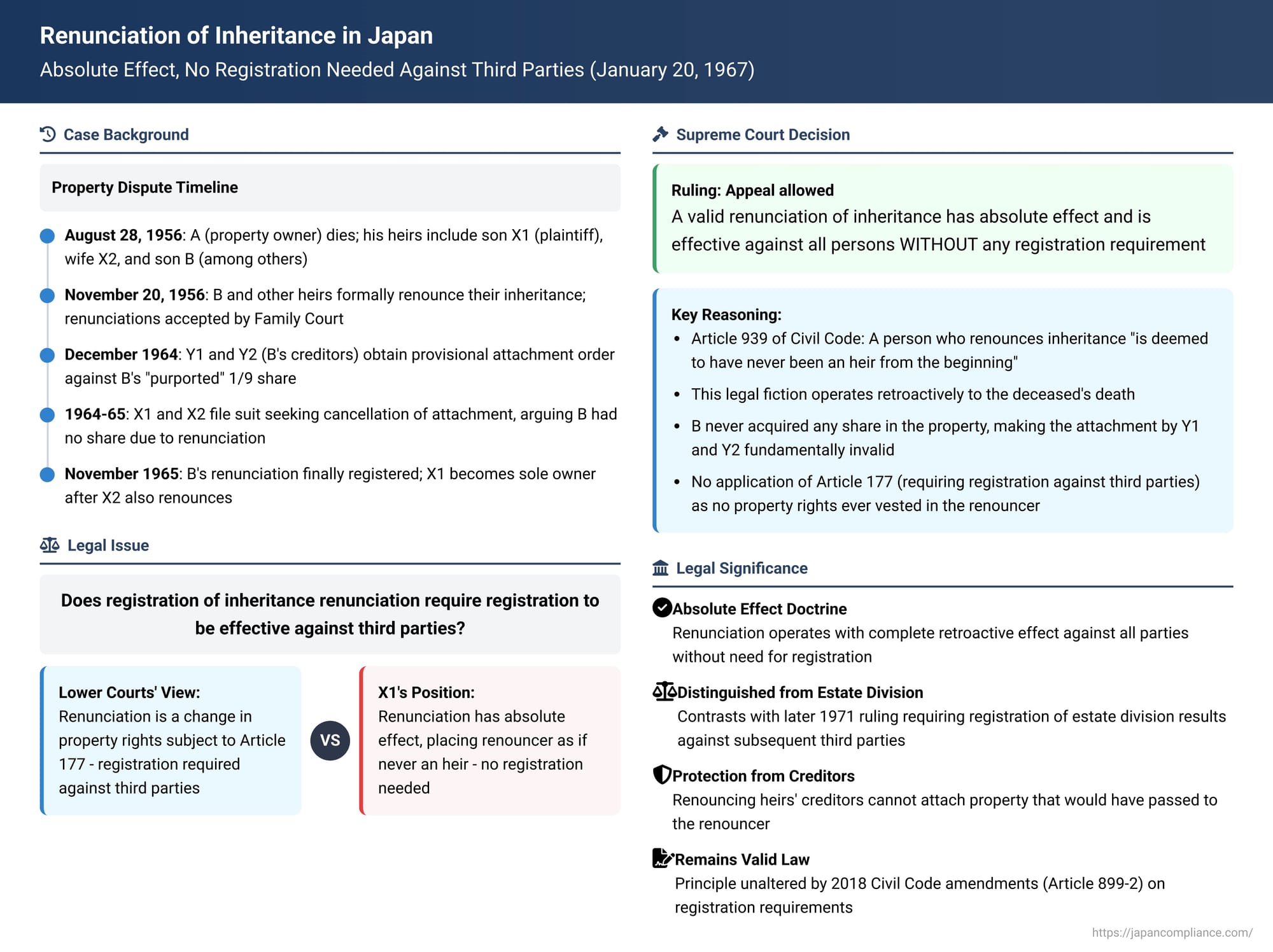

Renunciation of Inheritance in Japan: Absolute Effect, No Registration Needed Against Third Parties

Date of Judgment: January 20, 1967 (Showa 42)

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. Showa 41 (o) No. 457 (Third-Party Objection Suit)

When an individual inherits property, Japanese law provides a mechanism for them to "renounce" the inheritance (相続の放棄 - sōzoku no hōki) if they choose not to accept the assets and liabilities of the deceased. A critical question that arises is: what is the effect of such a renunciation on third parties, particularly creditors of the heir who has renounced? If an heir renounces their share, do the remaining heirs who consequently receive a larger portion of the estate need to register this change to protect their increased shares against those creditors? The Supreme Court of Japan delivered a definitive judgment on this issue on January 20, 1967, establishing the absolute nature of inheritance renunciation.

Facts of the Case: A Renounced Inheritance and a Creditor's Attachment

The case involved real property ("the Property") owned by A, who passed away on August 28, 1956.

- The Heirs and Renunciations: A had seven legal heirs. Among them were his eldest son, X1 (the plaintiff/appellant in the Supreme Court), and A's wife, X2 (an original plaintiff). All other heirs, including A's third son, B, lawfully renounced their inheritance by filing formal declarations with the Family Court. These renunciations were officially accepted by the court on November 20, 1956. However, at that time, no entries were made in the property register to reflect these renunciations or the consequently altered shares of the remaining heirs (X1 and X2).

- Creditors' Action Against the Renouncing Heir: Years later, in December 1964, Y1 and Y2 (creditors of B, the son who had renounced his inheritance) obtained a provisional attachment order (仮差押 - karisashiosae) against what they believed to be B's 1/9 statutory co-ownership share in the Property. To effect this attachment, Y1 and Y2, acting by way of subrogation on B's behalf, first procured an ownership preservation registration (所有権保存登記 - shoyūken hozon tōki) for the Property. This initial registration was made incorrectly, listing all seven original heirs, including B, as co-owners according to their original statutory shares (as if no renunciations had occurred). Immediately after this, Y1 and Y2 registered their provisional attachment against B's purported 1/9 share as shown in this faulty registration.

- Lawsuit by the Remaining Heirs: X1 and X2 (who, as a result of the other heirs' renunciations, became the sole effective heirs of A) filed a "third-party objection lawsuit" (第三者異議の訴え - daisansha igi no uttae). They argued that B, having validly renounced his inheritance, owned no part of the Property. Therefore, the attachment by Y1 and Y2 against his supposed share was invalid. They asserted that the Property belonged entirely to them (X1 and X2).

- Developments During Litigation: While the case was ongoing, in November 1965, the renunciations by B and the other heirs were finally registered. On the same day, X2 (A's wife) also formally renounced her share in the Property (presumably this was a renunciation of her inherited share from A, effectively consolidating ownership in X1, or a disposition of her share to X1; the judgment details confirm this ultimately left X1 as sole owner). This action by X2 was also registered shortly thereafter. The lawsuit's objective was subsequently focused on seeking the cancellation of the attachment registration.

- Lower Court Rulings: Both the Nagoya District Court (first instance) and the Nagoya High Court (on appeal) ruled against X1 (and X2). The lower courts held that a renunciation of inheritance constitutes a change in real property rights, thereby falling under Article 177 of the Civil Code, which generally requires registration to assert such changes against third parties. Since B's renunciation had not been registered at the time Y1 and Y2 (B's creditors) attached B's apparent statutory share, the lower courts concluded that X1 and X2 could not assert the legal effect of B's renunciation (and their consequently increased ownership of the Property) against these creditors.

- Appeal by X1: X1 appealed this adverse decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Renunciation's Effect is Absolute

The Supreme Court overturned the decisions of the lower courts and ruled decisively in favor of X1. It ordered the cancellation of the provisional attachment registration that Y1 and Y2 had placed on B's purported share.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Interpretation of Article 939 of the Civil Code (Effect of Renunciation): The Court examined Article 939, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code. It noted that both the pre-1962 amendment version (which stated that renunciation "is retroactive to the time of the commencement of inheritance") and the then-current (post-1962 amendment) version (which states that "a person who has renounced inheritance is deemed, with respect to that inheritance, to have never been an heir from the beginning") should be understood as having the same fundamental legal effect concerning the renouncer's status.

- Purpose of Renunciation Provisions: The Civil Code provides a specific period (the "deliberation period" under Article 915) during which an heir can choose to accept or renounce an inheritance. The Court emphasized that the purpose of this system is to protect the interests of heirs by not compelling them to unconditionally succeed to the deceased's rights and obligations.

- Absolute and Retroactive Effect of Renunciation: When an heir duly renounces their inheritance by filing a formal declaration with the Family Court (as required by Article 938) within the prescribed period, that heir is, by operation of law, placed in the same legal position as if the inheritance had never occurred for them. This effect is retroactive to the moment of the deceased's death.

- No Registration Required Against Third Parties: Crucially, the Supreme Court declared that this effect of renunciation is absolute and is effective against all persons, without the need for registration or any other formality to perfect it against third parties.

Application to the Case:

- Since B had validly renounced his inheritance from A in 1956, he was legally deemed never to have been an heir to A from the moment of A's death.

- Consequently, B never acquired any share or interest in the Property.

- The ownership preservation registration procured by Y1 and Y2 in 1964, which listed B as a co-owner holding a 1/9 share, was contrary to the true legal state of affairs and was therefore invalid with respect to B's purported share.

- It followed that the provisional attachment levied by Y1 and Y2 against B's non-existent share was also invalid, and its registration had no legal basis. X1, as the rightful sole owner (after X2's subsequent renunciation), was entitled to have this invalid attachment registration cancelled.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1967 Supreme Court judgment is a cornerstone of Japanese inheritance law, firmly establishing the nature and effect of inheritance renunciation:

- Renunciation's Effect is Absolute and Unconditional Against Third Parties: The most significant principle from this case is that a valid renunciation of inheritance operates absolutely. The renouncing heir is treated as if they were never an heir from the beginning, and this legal fiction is effective against everyone, including third parties like creditors of the renouncer. The remaining heirs (or those next in line of succession) acquire their increased shares automatically and do not need to register the renunciation to assert their full rights against such third parties. Article 177 of the Civil Code (requiring registration to perfect real rights against third parties) does not apply to the shift in ownership interests among heirs resulting from a renunciation.

- Rationale for the "Absolute Effect" and No Registration Requirement:

- "Never an Heir" Status: The core of this doctrine is the statutory effect of renunciation: the individual is legally erased from the line of succession for that particular inheritance. This means no property rights from that inheritance ever vest in them. Since no rights vested, there's no subsequent "transfer" or "loss" of rights by the renouncer that would typically engage Article 177 concerning transactions with third parties. The property simply passes to those who would have inherited had the renouncer not been in the picture from the start.

- Protecting the Heir's Freedom to Renounce: The system allowing heirs to renounce an inheritance is primarily for their protection, enabling them to avoid unwanted debts or responsibilities. If the effectiveness of this personal decision against third parties depended on registration, it could undermine the heir's ability to cleanly detach from the inheritance.

- Limited Timeframe for Renunciation: As noted in legal commentary and contrasted with estate division in later Supreme Court cases (e.g., the Showa 46.1.26 decision), renunciation usually must occur within a relatively short period (typically three months) after the heir becomes aware of the inheritance. Furthermore, if an heir engages in acts that imply acceptance of the inheritance (e.g., disposing of estate assets), they generally lose the right to renounce. This relatively confined timeframe and the conditions for renunciation reduce the likelihood of third parties being extensively misled by an heir's apparent status before a renunciation becomes effective.

- Clear Distinction from Estate Division (遺産分割 - Isan Bunkatsu): This ruling is often contrasted with the Supreme Court's different approach to estate division. In the case of an estate division agreement, if heirs decide to allocate property in shares that differ from their initial statutory shares, they do need to register this outcome to protect their specific entitlements against third parties who might acquire interests after the division agreement but before its registration. The Supreme Court (in the Showa 46.1.26 judgment) differentiated the two situations by pointing to factors like the explicit statutory limitation on the retroactivity of estate division against certain third parties (Article 909 proviso, Civil Code)—a limitation not found for renunciation—and the greater practical likelihood of third parties forming interests based on pre-division appearances over the often longer period it takes to finalize an estate division.

- Consequences for Creditors of a Renouncing Heir: This decision makes it clear that creditors of an individual who validly renounces an inheritance cannot look to the assets that would have passed to that individual had they not renounced. The renunciation effectively prevents those assets from ever becoming part of the renouncer's patrimony for that specific inheritance, thus placing them beyond the reach of that renouncer's personal creditors in that context.

- Consistency with Modern Legislative Reforms (Article 899-2 of the Civil Code): The PDF commentary accompanying this case discusses the 2018 amendments to the Civil Code, particularly the introduction of Article 899-2. This new article generally requires registration for an heir to assert inherited rights that exceed their statutory inheritance share against third parties. However, the commentary clarifies that Article 899-2 was not intended to alter the established case law concerning the absolute effect of inheritance renunciation. The principle from this 1967 judgment remains good law. This is typically reconciled by understanding that when an heir renounces, the remaining heirs do not acquire shares "exceeding" their own statutory portion in a way that triggers Article 899-2; rather, their statutory shares are recalculated based on a new pool of heirs (excluding the renouncer), and they inherit these recalculated statutory shares directly and absolutely. The renouncer is treated as a "non-owner" (無権利者 - mukenrisha) from the start regarding that inheritance, so creditors attaching the "renouncer's share" are attaching a nullity.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1967 judgment on inheritance renunciation is a fundamental decision in Japanese succession law. It firmly establishes that a valid renunciation has an absolute and retroactive effect, deeming the renouncer to have never been an heir for that specific inheritance. Consequently, the remaining heirs (or those next in line) acquire their enhanced shares automatically, and they do not need to register the effects of the renunciation to assert their full ownership against third parties, including creditors of the renouncing individual. This principle, which prioritizes the heir's freedom to refuse an unwanted inheritance and the definitive legal consequences of that choice, remains a cornerstone of Japanese inheritance practice, undisturbed by more recent legislative reforms concerning the registration of other types of inherited property rights.