Rent from Inherited Property: How is it Divided Before Estate Settlement? A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: September 8, 2005

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Case No. Heisei 16 (Ju) No. 1222 (Claim for Return of Deposited Money)

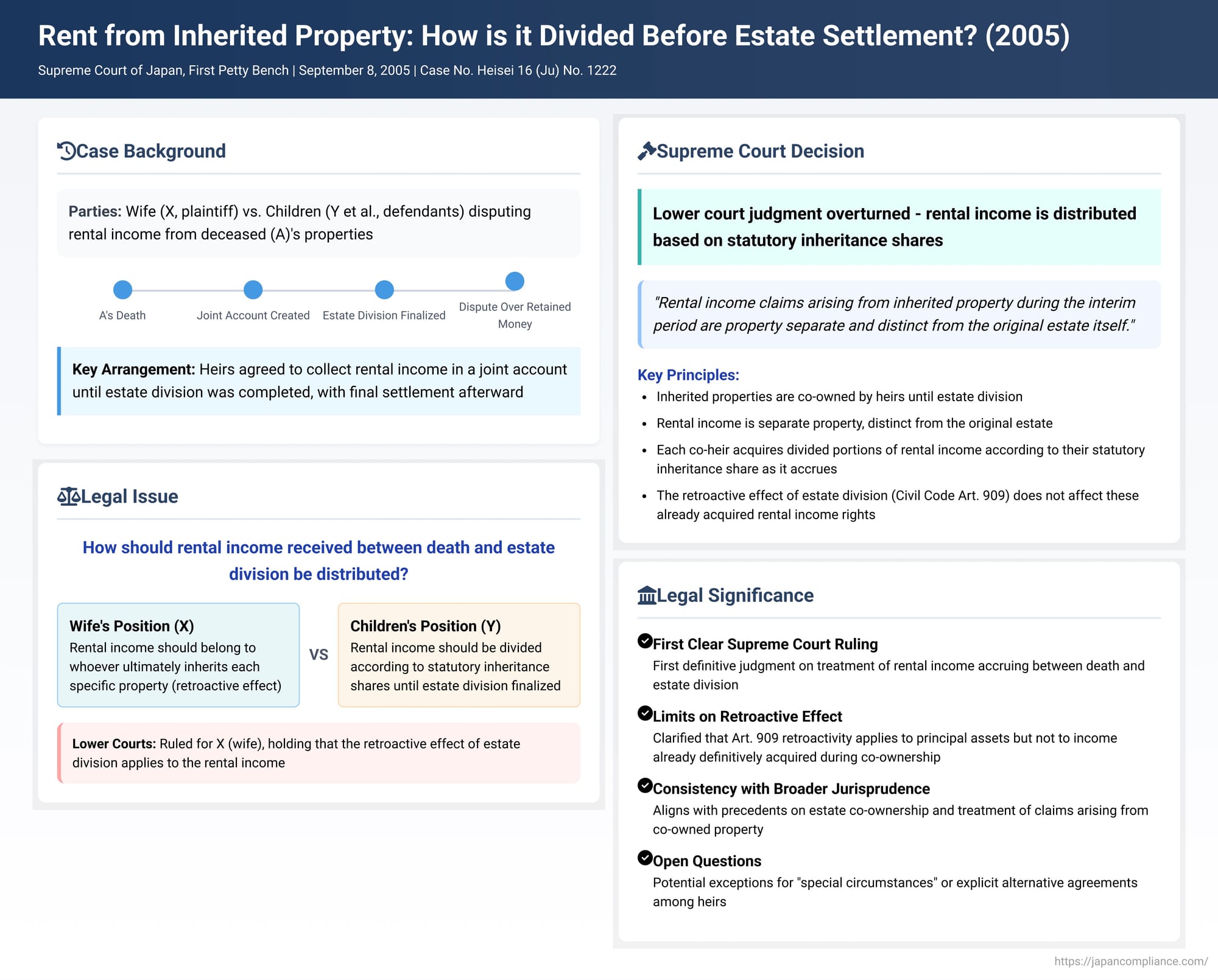

When an individual passes away leaving behind rental properties, a common question arises: how should the rental income generated after their death but before the estate is formally divided be distributed among the co-heirs? Does this income retroactively belong to the heir who eventually inherits the specific property, or is it divided among all co-heirs based on their statutory inheritance shares as it accrues? The Supreme Court of Japan provided a clear answer to this long-debated issue in its decision on September 8, 2005.

Facts of the Case

The dispute involved the family of the deceased, A, and the rental income from properties in A's estate.

- The Heirs and the Estate: A passed away, leaving his wife, X (the plaintiff), and their children, Y (the specific defendant representing the children's group), B, C, and D, as legal heirs. A's estate included several real estate properties that were generating rental income (referred to as the "Properties").

- Agreement on Rental Income Management: The heirs (X and Y et al.) mutually agreed that rental income and management expenses arising from the Properties would be handled through a specially opened joint bank account (the "Joint Account"). They also agreed that a final settlement of these accumulated funds would occur once the ownership of the Properties themselves was determined through formal estate division. Tenants were instructed to pay rent into this Joint Account, and property management expenses were paid from it.

- Estate Division Finalized: The division of A's estate, including the allocation of the Properties, was eventually finalized by a court decision (the "Estate Division Decision".

- Dispute Over Accumulated Rental Income: Following the Estate Division Decision, a dispute arose between X and Y et al. regarding the method of distributing the remaining balance in the Joint Account (the "Retained Money").

- X's Position: X argued that the rental income generated from each specific property should retroactively belong to the heir who was ultimately awarded that particular property in the Estate Division Decision. This was based on the principle that estate division has a retroactive effect to the time of the deceased's death (Article 909 of the Civil Code).

- Y et al.'s Position: Y and the other children contended that the rental income generated up to the date the Estate Division Decision became final should be divided among all co-heirs according to their respective statutory inheritance shares. Only the rental income generated after the finalization of the Estate Division Decision should belong exclusively to the heir who received the specific income-generating property.

- The Lawsuit: The heirs distributed the undisputed portion of the funds from the Joint Account. They further agreed that Y would hold the disputed Retained Money, and its ultimate ownership would be determined by a court lawsuit. Consequently, X sued Y to claim the Retained Money, asserting that X's calculation method (based on retroactive ownership of the properties) was correct.

- Lower Court Rulings: Both the first instance court and the High Court ruled in favor of X. They held that legal fruits (like rental income) arising from an estate inherently belong to the person who owns the principal property. Since estate division has a retroactive effect, the heir who acquires a specific property through estate division is deemed to have acquired the legal fruits generated by that property from the time of the deceased's death. Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings based on a different interpretation of the law.

The Supreme Court laid out the following core principles:

- Inherited Property as Co-owned: From the commencement of inheritance (death of the deceased) until the completion of estate division, inherited property is held in co-ownership by the co-heirs.

- Rental Income as Separate Property: Rental income claims (which are monetary claims) arising from the use and management of inherited rental real estate during this interim period are considered property separate and distinct from the original estate itself.

- Definitive Acquisition by Co-heirs: Each co-heir definitively acquires a divided portion of these rental income claims as a sole and separate creditor, corresponding to their statutory inheritance share, as this income accrues. This is based on the general principle that divisible monetary claims are automatically divided among multiple creditors (a principle related to Article 427 of the Civil Code).

- Retroactivity of Estate Division Not Affecting Acquired Rent: While estate division does have a retroactive effect to the time of inheritance (Article 909 of the Civil Code), this retroactivity pertains primarily to the title of the principal inherited assets themselves. The Supreme Court held that the ownership of rental income claims, which have already been definitively and separately acquired by the co-heirs according to their inheritance shares during the co-ownership period, is not affected by a subsequent estate division.

Application to the Case:

Based on these principles, the Supreme Court concluded that the rental income generated from the Properties between A's death and the finalization of the Estate Division Decision was acquired by X and Y et al. as divided, sole claims according to their respective statutory inheritance shares. The Retained Money in the Joint Account, therefore, should be settled and distributed based on this understanding, not on the basis of who eventually inherited each specific property.

The Supreme Court found that the High Court's decision, which applied a different interpretation and awarded the Retained Money based on the retroactive ownership of the principal properties, constituted an error in the application of law that clearly affected the judgment.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 2005 Supreme Court decision was a landmark ruling, providing much-needed clarity on a frequently disputed issue in Japanese inheritance law.

- First Clear Supreme Court Stance: This was the first time the Supreme Court explicitly ruled on how rental income accruing from co-owned inherited real estate after the deceased's death but before formal estate division should be allocated.

- Nature of Post-Inheritance Rental Income Confirmed: The Court definitively characterized such rental income not as part of the original inheritable estate, but as new, separate property derived from the management of co-owned estate assets during the co-ownership period. This is crucial because it means these funds are not subject to the same rules of division as the original estate assets themselves.

- Application of Automatic Division for Divisible Claims: The ruling applies the principle of automatic division (as per Article 427 of the Civil Code for divisible claims) to these rental income claims. Each co-heir is deemed to become an independent creditor for their portion of the rent as it becomes due, based on their statutory inheritance share.

- Limitation on Retroactivity of Estate Division: A key takeaway is the Court's stance on the limits of Article 909's retroactive effect. While the ownership of the principal assets (the real estate) is determined retroactively, this does not extend to undoing the separate and definitive rights to income that accrued to the co-heirs during the period of co-ownership. The commentary suggests that overturning these established rights to accrued income would be detrimental to legal stability.

- Consistency with Broader Jurisprudence: Legal commentary indicates that this decision aligns with other Supreme Court precedents concerning the nature of estate co-ownership and the treatment of other types of claims arising from co-owned property, such as damages claims.

- Overruling Conflicting Lower Court Approaches: Prior to this judgment, lower courts and legal scholars held various views on this issue. Some treated such rental income as part of the estate itself, others as co-owned property requiring separate partition, and yet others (like the lower courts in this case) applied the retroactive effect of estate division. This Supreme Court decision provided a unifying and authoritative interpretation, effectively overriding approaches that suggested such rental income would retroactively belong to the eventual inheritor of the source property.

Scope, Context, and Further Considerations

The specific facts of this case, where rental income was meticulously collected into a separate account and an agreement existed for its eventual settlement, provided a clear context for the Supreme Court's chosen approach. However, legal commentary raises points about the decision's broader applicability:

- "Special Circumstances": It is questioned whether the same direct conclusion would apply in all scenarios, such as if rental income had already been consumed by one co-heir, or if a different explicit agreement existed among the heirs regarding the treatment of rental income (e.g., an agreement that all rent would indeed follow the property's ultimate inheritor). The Court did not explicitly rule on the effect of such alternative agreements.

- Different Types of "Fruits" from an Estate: The ruling specifically addresses rental income from real estate. The commentary suggests further consideration is needed for how its principles might apply to other types of "fruits" or income generated by an estate. Examples include:

- Interest from bank deposits (especially since a 2016 Supreme Court Grand Bench decision held that bank deposits themselves are generally part of the divisible estate, not automatically divided ).

- Income from an actively managed business or agricultural land within the estate, where an heir’s labor and investment might significantly contribute to the income generated.

- Relationship with the 2016 Bank Deposit Ruling: The 2016 Grand Bench decision (Heisei 28.12.19), which determined that bank deposits are generally subject to estate division, emphasized the utility of such liquid assets in facilitating adjustments during the division process. While the 2005 rental income case deals with income generated after death, the underlying rationale of making liquid assets available for equitable division in the 2016 ruling could potentially influence future thinking about how accumulated rental income (especially if held as deposits) is handled, particularly if there are strong equitable reasons or agreements to do so. However, the 2005 ruling on the accrual of rent as separate, divided claims remains distinct.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2005 judgment provides a clear and significant directive: rental income generated from inherited real estate between the deceased's death and the finalization of estate division is to be considered separate property, definitively acquired by each co-heir according to their statutory inheritance share as it accrues. The retroactive effect of the estate division concerning the principal properties does not alter this established ownership of the accrued rental income. This ruling prioritizes legal stability and the nature of divisible monetary claims, offering crucial guidance for co-heirs managing income-producing assets during the often-complex period of estate settlement.