Renovations, Bankrupt Tenants, and Enriched Landlords: A Japanese Supreme Court Case on 'Appropriated Benefit' Claims

Date of Judgment: September 19, 1995

Case Name: Claim for Return of Unjust Enrichment

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction

In the world of construction and services, a frustrating scenario can arise: a contractor performs work for a client, enhancing the value of an asset. However, the client then becomes insolvent and unable to pay. If that asset (say, a renovated building) is owned by a third party (like a landlord), who ultimately enjoys the benefit of the contractor's unpaid work, can the contractor directly sue that third-party owner for unjust enrichment? This complex legal question, known in Japanese jurisprudence as a "Tenyōbutsu So-ken" (転用物訴権 – roughly, a claim for an "appropriated object" or "appropriated benefit"), was addressed by the Japanese Supreme Court in a significant decision on September 19, 1995.

The Restaurant Renovation and Financial Fallout: The Facts

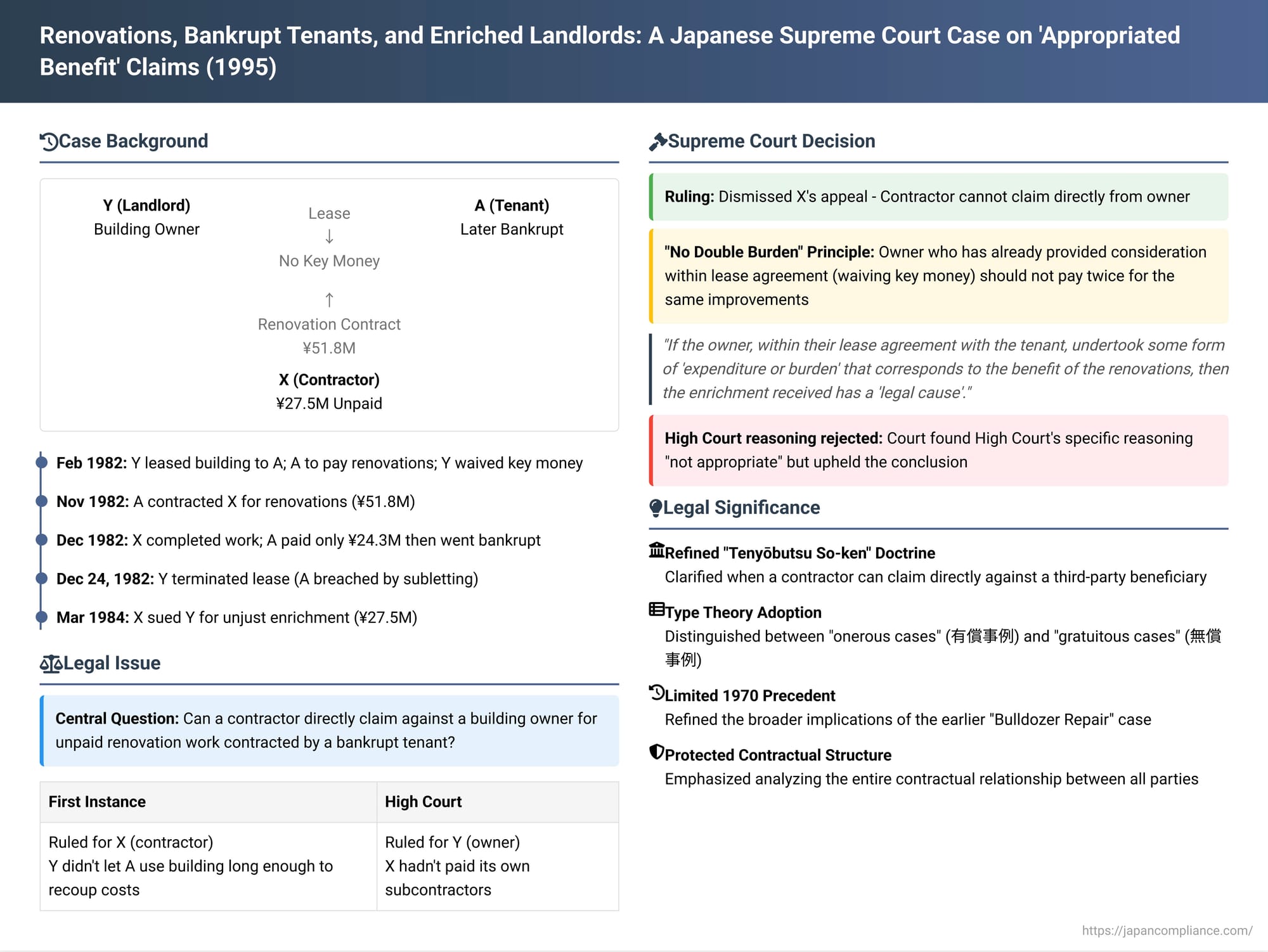

The case unfolded as follows:

- The Parties and Initial Lease:In February 1982, Y (the owner) leased Building Kō to A (the tenant) under a "Head Lease." This lease had a crucial term: A was to bear all costs for any repairs and renovations to Building Kō. In return for A taking on this financial responsibility for improvements, Y agreed to waive the "key money" or "premium" (権利金 - kenrikin) – a substantial upfront payment typically expected from a commercial tenant undertaking such a venture. The lease also prohibited A from sub-letting without Y's consent.

- Y: The owner of a building (let's call it "Building Kō").

- A: An individual who planned to renovate Building Kō into a multi-use commercial space with a restaurant, boutiques, etc.

- X (Tenpo Kōgyō K.K.): A construction contractor.

- The Renovation Contract and Work: In November 1982, A (the tenant) entered into a contract with X (the contractor) for X to carry out the planned renovations of Building Kō for a total price of approximately ¥51.8 million. X completed the renovation work, largely using its own sub-contractors, and handed over the improved Building Kō to A in early December 1982.

- Tenant's Default and Bankruptcy: A paid X about ¥24.3 million of the renovation cost but defaulted on the remaining balance of approximately ¥27.5 million. By the end of December 1982, A had effectively gone bankrupt, became unreachable, and had no discernible assets from which X could recover the outstanding payment.

- Landlord Terminates Lease: Meanwhile, A had also breached the Head Lease with Y, including by sub-letting parts of the renovated Building Kō to third parties without Y's consent. Consequently, on December 24, 1982, Y (the owner) terminated the Head Lease with A and subsequently regained possession of the (now renovated) Building Kō.

- Contractor Sues Owner for Unjust Enrichment: In March 1984, X (the unpaid contractor) sued Y (the building owner). X argued that Y had been unjustly enriched because Y now possessed a renovated, more valuable building due to X's labor and materials, for which X had not been fully paid. X claimed that Y had received this benefit without legal cause at X's expense and sought payment of the outstanding ~¥27.5 million.

- Lower Court Rulings:

- The first instance court ruled in favor of X (the contractor). It reasoned that although Y had not received key money from A, Y had not allowed A to use the building for a sufficient period for A to recoup the renovation investment. Thus, Y had obtained the increased value of the building "for free" and should compensate X for the existing benefit.

- The High Court, however, reversed this decision and ruled in favor of Y (the owner), dismissing X's claim. Its reasoning was somewhat different: it suggested X hadn't truly suffered a loss because X itself had not yet paid its own sub-contractors for their part of the work.

X appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court, on September 19, 1995, dismissed X's appeal. While it found the High Court's specific reasoning (about X not having paid its sub-contractors) to be "not appropriate," it ultimately upheld the High Court's conclusion that X's claim against Y should be dismissed. The Supreme Court provided its own distinct reasoning based on the principles of unjust enrichment in three-party situations.

Core Reasoning – The "No Double Burden" on the Owner Principle:

- General Condition for Owner's Liability to Contractor: The Court stated that if a contractor (X) renovates a building under a contract with a tenant (A), and the tenant subsequently becomes insolvent, making the contractor's claim against the tenant worthless, the building owner (Y) can be said to have been unjustly enriched at the contractor's (X's) expense only if, when looking at the entire lease agreement between the owner (Y) and the tenant (A), the owner (Y) received the benefit of those renovations without any corresponding counter-performance or burden on Y's part within that Y-A lease.

- The Effect of Owner's Consideration to Tenant: If the owner (Y), within the terms of their lease agreement with the tenant (A), undertook some form of "expenditure or burden" (出捐ないし負担 - shutsuden naishi futan) that corresponds to the benefit of the renovations, then the enrichment the owner (Y) received (the improved building) is deemed to have a "legal cause" (法律上の原因 - hōritsu-jō no gen'in) stemming from that Y-A lease agreement.

- Avoiding Double Burden: To allow the contractor (X) to claim unjust enrichment directly from the owner (Y) in such a situation – where Y has already effectively "paid for" or given consideration for the improvements through the terms of the Y-A lease – would result in imposing a "double burden" (二重負担 - nijū futan) on the owner. The owner would have effectively given value once to A (e.g., by forgoing key money in exchange for A bearing renovation costs) and would then be forced to pay again to X for the same improvements. The law of unjust enrichment does not typically permit such an outcome.

Application to the Facts of This Case:

- The Supreme Court found that the benefit Y (the owner) received from X's renovation work was directly offset by the burden Y had accepted in the Head Lease with A: Y waived the right to receive key money from A. This waiver of a substantial upfront payment was Y's consideration or "burden" undertaken in exchange for A being responsible for all renovation costs.

- Therefore, the enhanced value of Building Kō that Y ultimately retained was not a benefit received "without legal cause." Its legal cause was rooted in the terms of the Head Lease with A.

- The fact that the Head Lease between Y and A was later terminated due to A's own defaults (like unauthorized sub-letting) did not retroactively erase the original legal basis upon which Y was entitled to benefit from A-funded renovations.

Thus, Y was not unjustly enriched at X's expense without legal cause, and X's claim against Y failed.

Understanding "Tenyōbutsu So-ken" (Appropriated Benefit Claims)

This 1995 Supreme Court decision is a key case in the development of the "Tenyōbutsu So-ken" doctrine in Japanese unjust enrichment law. It significantly refines how these three-party benefit situations are analyzed.

The Earlier 1970 "Bulldozer Repair" Case:

A much-discussed prior Supreme Court case (July 16, 1970) had appeared to allow such claims more broadly. In that case, a contractor repaired a bulldozer for a lessee, who then went bankrupt. The owner of the bulldozer got it back in its repaired (more valuable) state. The Supreme Court indicated the contractor could have a direct unjust enrichment claim against the owner if the contractor's claim against the insolvent lessee was worthless, finding a "direct causal link" between the contractor's loss (unpaid repair work) and the owner's gain (a repaired bulldozer). This was suggested even if the owner-lessee lease stipulated that the lessee would bear repair costs in exchange for lower rent (an "onerous" or "with consideration" relationship for the benefit).

Academic Criticism and the "Type Theory":

Many legal scholars criticized the potentially overly broad implications of the 1970 ruling, particularly its application where the ultimate beneficiary (the owner) had, in their own separate contract with the intermediary (the lessee), already provided some form of consideration for the benefit received. This led to the development of "type theories" (類型論 - ruikeiron) which categorized these three-party situations:

- "Onerous Cases" (有償事例 - yūshō jirei): Where the ultimate beneficiary (Y) has provided consideration to the intermediary (A) for the benefit that originated from the claimant (X). Examples: Y leases property to A at a lower rent because A agrees to pay for repairs/improvements; or, as in the 1995 case, Y waives key money because A agrees to pay for renovations. In these "onerous cases," scholars argued that allowing X to claim directly from Y would unfairly make Y pay twice for the same benefit. Thus, X's claim against Y should generally be denied.

- "Gratuitous Cases" (無償事例 - mushō jirei): Where Y receives the benefit from A (originating from X's efforts) completely for free, without any corresponding burden or consideration given to A. In these "gratuitous cases," the argument for allowing X to claim directly from Y is stronger, as Y would otherwise be truly "unjustly" enriched at X's ultimate expense if A is insolvent.

- "Claim-Holding Cases" (債権保有事例 - saiken hoyū jirei): Situations where the intermediary (A) might actually have a valid claim against the ultimate beneficiary (Y) for the value of the improvements (e.g., under rules for reimbursement of necessary or beneficial expenses on leased property). In such cases, X's remedy should arguably be channeled through A (e.g., by X exercising A's claim against Y via subrogation, or A recovering from Y and then paying X), rather than a direct claim by X against Y that might bypass A's other creditors.

The 1995 Judgment's Alignment with "Onerous Case" Analysis:

The 1995 Supreme Court decision clearly adopts the logic applied to "onerous cases." By finding that Y (the owner) had provided consideration to A (the tenant) – in the form of waiving key money – in exchange for A undertaking the renovation costs, the Court established that Y's enrichment had a "legal cause." This directly addresses the concern about imposing a double burden on Y.

Relationship Between the 1995 and 1970 Judgments:

Legal commentary suggests that the 1995 judgment does not necessarily represent a complete overruling of the 1970 "bulldozer" case but rather a significant refinement and limitation of its perceived scope. The 1970 case's binding precedent might be limited to establishing that a "direct causal link" can exist between X's loss and Y's gain in such three-party situations. The factual details of the "onerous" nature of the owner-lessee lease in the 1970 case were reportedly fully established only on remand, meaning the Supreme Court in 1970 was not ruling on a clearly defined "onerous case" at its level. The broader pronouncements in the 1970 case about the contractor's right to claim from the owner if the intermediary is insolvent may have been more in the nature of guidance (obiter dictum) than strictly binding law for all future scenarios. The 1995 decision then clarifies that in clearly "onerous" situations, the owner is protected.

Conclusion

The 1995 Supreme Court decision significantly shaped the understanding of "Tenyōbutsu So-ken" or "appropriated benefit" unjust enrichment claims in Japanese law, particularly in common three-party scenarios involving landlords, tenants, and contractors. It established a crucial principle: when a property owner has already provided consideration or borne a burden within their own contractual relationship (e.g., with their tenant) in exchange for improvements to their property, a contractor who performed those improvements under a separate contract with the tenant (and who remains unpaid due to the tenant's insolvency) generally cannot succeed in a direct unjust enrichment claim against the property owner. This approach aims to prevent the owner from being unfairly subjected to a "double burden" and directs the contractor's primary risk of non-payment back to the party with whom they directly contracted – the tenant. The ruling emphasizes the importance of analyzing the entirety of the contractual relationships involved to determine if an ultimate beneficiary's gain truly lacks legal cause at the claimant's expense.