Remote Care, Tragic Outcome: Japan's Supreme Court on Psychiatrist's Liability in Outpatient Suicide

Date of Decision: March 12, 2019, Supreme Court of Japan (Third Petty Bench)

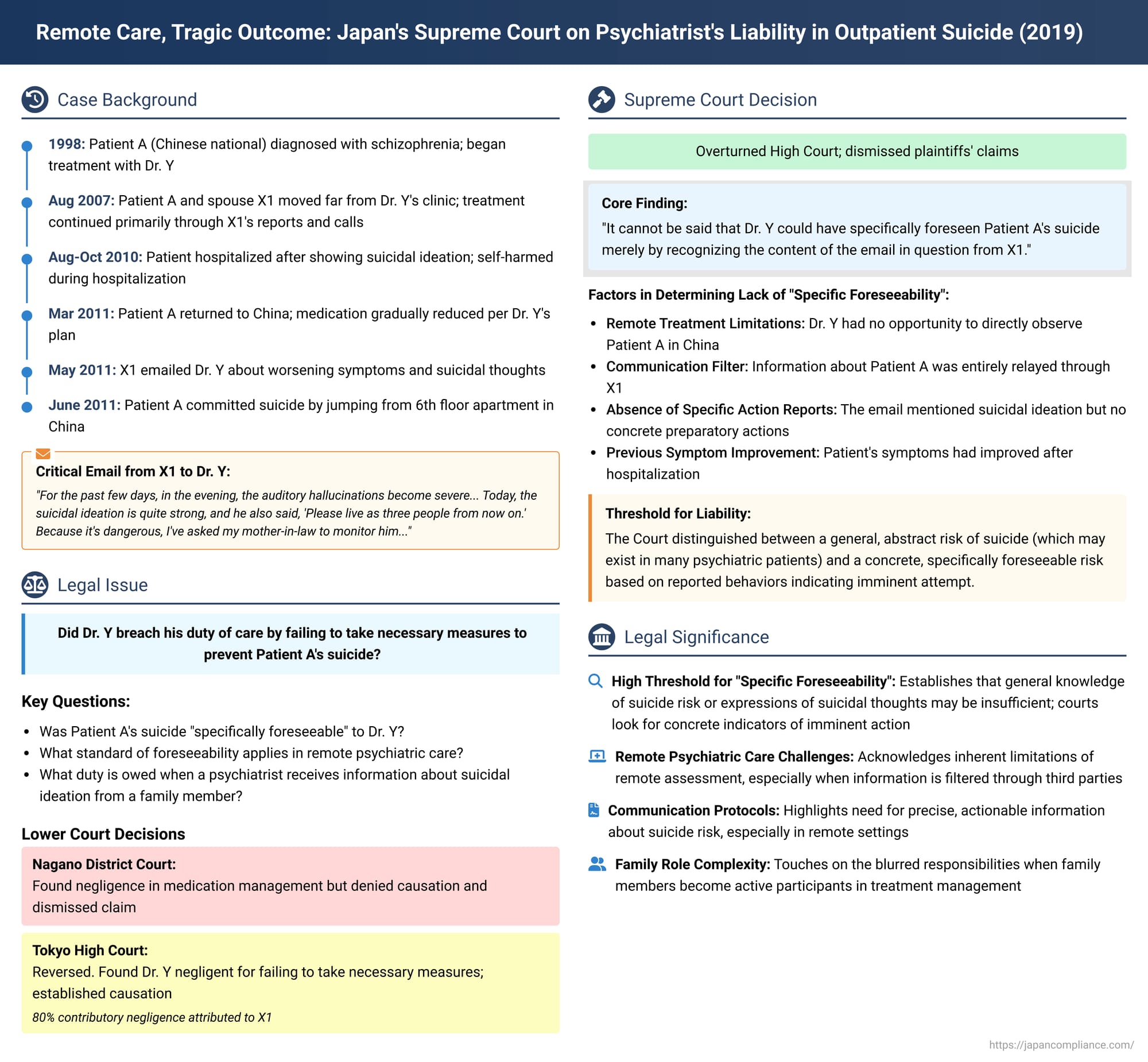

The duty of care for medical professionals, particularly psychiatrists, in preventing patient suicide is a profoundly challenging area of law and ethics. This responsibility becomes even more complex when treating outpatients, especially those managed remotely. A significant Japanese Supreme Court decision on March 12, 2019, addressed such a case, ruling on the liability of a psychiatrist after the suicide of a long-term schizophrenic patient who was primarily being treated through communications with his spouse while residing abroad. The judgment provides crucial insights into the legal standard of "foreseeability" required to establish a breach of duty in these difficult circumstances.

The Patient's History and Treatment Journey

The case involved Patient A, a Chinese national who married X1 in Japan in 1994. Patient A was diagnosed with schizophrenia in January 1998 and began receiving treatment from Dr. Y, initially at a hospital where Dr. Y worked, and later at Dr. Y's private clinic from June 2001.

A significant aspect of their long-term therapeutic relationship was the shift to remote management. Around August 2007, Patient A and X1 moved to Nagano Prefecture, a considerable distance from Dr. Y's clinic in Tokyo. Thereafter, Patient A himself rarely visited the clinic. Instead, X1 (Patient A's spouse) primarily communicated Patient A's symptoms to Dr. Y, either through clinic visits, phone calls, or emails, and Dr. Y would prescribe antipsychotic medications based on this information. Patient A was not fluent in Japanese, and Dr. Y largely relied on X1 for information regarding A's condition.

Deterioration and Hospitalization in 2010:

In March 2010, Patient A began experiencing auditory hallucinations. By August 2010, his condition worsened, and he exhibited suicidal ideation, including an instance of wandering with a belt. This led to his admission to B University Hospital's psychiatric ward under a medical protection order (a form of involuntary commitment for individuals at risk to themselves or others). He was placed in isolation due to the imminent risk of suicide or self-harm. During this hospitalization, in September 2010, Patient A engaged in a self-harm act, cutting his left wrist with a razor. By October 2010, his symptoms, including hallucinations and suicidal thoughts, reportedly decreased, and he was discharged.

Post-Discharge Care by Dr. Y (November 2010 - March 2011):

Following his discharge from B University Hospital, Patient A had in-person consultations with Dr. Y once a month from November 2010 to January 2011. Dr. Y noted that the antipsychotic medication prescribed by B University Hospital was of multiple types and in high dosages. Believing a reduction was necessary, Dr. Y explained this treatment strategy to both Patient A and X1. X1 had informed Dr. Y about Patient A's self-harm incident (the razor cut) at B University Hospital.

In February 2011, X1 emailed Dr. Y, providing an update on Patient A's medication adherence and reporting a reduced frequency of severe hallucinations. X1 also informed Dr. Y that Patient A was planning to return to his family home in China for a period.

On March (day unspecified), 2011, Patient A, accompanied by X1, had an in-person consultation with Dr. Y. Dr. Y advised that, due to the potential stress of environmental changes, Patient A should maintain his current medication dosage for one month after arriving in China. After that, a gradual reduction could be considered based on his condition. The following day, Patient A departed for China alone.

The Crisis and Tragic Outcome in China

From April 2011, Patient A's antipsychotic medication was gradually reduced as per Dr. Y's plan. However, during May 2011, his auditory hallucinations worsened, and suicidal ideation re-emerged. Patient A expressed to X1 an urge to jump from his family's 6th-floor apartment. X1 traveled to China to assess Patient A's condition and returned to Japan.

On May (day unspecified), 2011, X1 sent an email to Dr. Y (referred to as "the email in question" - 本件電子メール, honken denshi mēru). This email conveyed critical information:

"For the past few days, in the evening, the auditory hallucinations become severe, and it seems he's also experiencing oculogyric crises. Today, the suicidal ideation is quite strong, and he also said, 'Please live as three people [referring to X1 and their two children] from now on.' Because it's dangerous, I've asked my mother-in-law to monitor him, and I told him to return his Seroquel dosage to 11mg... Please show me the outlook for what lies beyond medication reduction."

Around May 30, 2011, Dr. Y replied to X1's email, stating, "If it becomes difficult, we may need to consider hospitalization for medication adjustment."

It was noted that after this crucial email exchange, X1 did not convey any further information to Dr. Y suggesting an imminent, acute suicidal crisis or specific preparatory actions by Patient A.

In June 2011, Patient A complained of hallucinations. Later that month, he committed suicide by jumping from his family's 6th-floor apartment in China.

The Legal Battle: From Negligence Finding to Reversal

Patient A's family (X1, and their children X2 and X3) filed a lawsuit against Dr. Y, alleging breach of his duty of care. They argued that Dr. Y was negligent in failing to take necessary emergency measures to prevent Patient A's suicide, seeking damages based on breach of contract or tort.

- Trial Court (Nagano District Court, Matsumoto Branch):

- The court denied that Dr. Y was negligent for failing to implement hospitalization measures.

- However, it found Dr. Y negligent in his medication management, concluding he should have halted the medication reduction and either reverted to the previous prescription or prescribed a different antipsychotic.

- Despite this finding of negligence, the trial court ultimately dismissed the claim. It denied causation, reasoning that even if Dr. Y had changed the medication, it would typically take 2-4 weeks for such changes to take effect, and therefore, a "high probability of avoiding the suicide" could not be established.

- High Court (Tokyo High Court):

- The High Court reversed the trial court's decision. It found Dr. Y negligent for "failing to take necessary measures such as specific instructions for medication increase, thorough monitoring, and hospitalization measures to prevent the said suicide."

- It also found a causal link between this negligence and Patient A's suicide.

- However, the High Court significantly reduced the damages, attributing 80% of the responsibility to X1 as contributory negligence. It reasoned that X1 also had a duty, based on good faith, to take measures to prevent the suicide, and that X1's active involvement in Patient A's care (including medication adjustments and symptom reporting) had rendered Dr. Y's own grasp of Patient A's condition insufficient.

Dr. Y appealed the High Court's finding of liability to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (March 12, 2019)

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision that had found Dr. Y liable. It ultimately dismissed the plaintiffs' claims, effectively reinstating the trial court's dismissal but on different grounds—namely, that Dr. Y had not breached his duty of care because Patient A's suicide was not specifically foreseeable to him.

Core Reasoning: Lack of Specific Foreseeability of Suicide

The Supreme Court meticulously analyzed the foreseeability aspect:

- Past History: The Court acknowledged Patient A's history of self-harm (the razor incident in September 2010 during his hospitalization at B University Hospital) and suicidal ideation. However, it also noted that his symptoms had improved, leading to his discharge, and that he had subsequently been under Dr. Y's care with a plan for gradual medication reduction.

- Remote Observation: A critical factor was that after Patient A returned to China in March 2011, Dr. Y had no opportunity to directly examine or observe him. His understanding of Patient A's condition was entirely dependent on information relayed by X1, primarily through phone calls and emails.

- Interpretation of "The Email in Question": The Supreme Court focused on the specific content of X1's email from May 2011. While the email did report that Patient A's "suicidal ideation is quite strong" and mentioned the "dangerous" situation, the Court highlighted that, in terms of Patient A's concrete words and actions, "it was merely conveyed that the patient had stated, 'Please live as three people from now on.'"

- No Indication of Concrete Suicidal Actions: The Court also noted that between Patient A's return to China in March 2011 and "the email in question" in late May 2011, "although he had expressed suicidal ideation, there was no indication of specific actions taken to attempt suicide."

Conclusion on Foreseeability: Based on this, the Supreme Court concluded:

"Even considering that Dr. Y was aware that reducing the dosage of antipsychotic medication could potentially worsen Patient A's symptoms, it cannot be said that Dr. Y could have specifically foreseen Patient A's suicide merely by recognizing the content of the email in question from X1."

Since the suicide was not deemed specifically foreseeable to Dr. Y based on the information he had, the Court held that "Dr. Y did not have a duty to take necessary measures to prevent Patient A's suicide."

Discussion: Foreseeability in Psychiatric Suicide Cases

This Supreme Court decision underscores the high threshold for establishing "specific foreseeability" of suicide, particularly for outpatients managed under challenging circumstances like remote care.

- Abstract vs. Concrete Risk: The ruling distinguishes between a general, abstract risk of suicide (which may be elevated in individuals with severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia, especially during medication changes) and a concrete, immediate, and specifically foreseeable risk of an actual suicide attempt.

- Importance of Behavioral Indicators: The Court appeared to place significant weight on the presence or absence of reported concrete actions or specific preparatory behaviors indicative of an imminent suicide attempt, as opposed to expressions of suicidal ideation alone, however strong those expressions might seem to a family member. The patient's reported statement, "Please live as three people from now on," while alarming, was not, in the Court's view, sufficient in itself to make the subsequent suicide specifically foreseeable to the remote physician.

- Challenges of Remote Assessment: The decision implicitly acknowledges the inherent limitations faced by psychiatrists in accurately assessing suicide risk when direct patient contact is absent and information is mediated by a third party (in this case, the spouse X1). The quality, detail, and interpretation of information conveyed by family members become critical, yet potentially fraught with subjective elements.

The Complexities of Remote Psychiatric Care

The facts of this case highlight several intricate issues in modern psychiatric practice:

- The Principle of In-Person Consultation: Japanese medical law (Physicians Act, Article 20) generally mandates in-person consultations. Dr. Y's reliance on X1 for information and prescription management for Patient A in China appears to diverge from this principle. However, legal and medical commentary notes that this rule is not always rigidly applied, and in certain psychiatric contexts—particularly involving long-term therapeutic relationships, geographical barriers, or specific patient needs (like language difficulties, as Patient A was not fluent in Japanese)—some flexibility has historically occurred, though not without legal risk.

- Role of Intermediaries and Family Caregivers: When family members become the primary conduits of information and active participants in medication management (as X1 was, even adjusting dosages based on her own assessment), the lines of responsibility between the physician and the caregiver can become blurred. This can impact the physician's ability to make independent, direct assessments of the patient's mental state and any acute changes. The High Court's finding of significant contributory negligence on X1's part, though ultimately rendered moot by the Supreme Court's decision on Dr. Y's primary liability, reflects this complexity.

Broader Implications for Psychiatric Practice

The Supreme Court's 2019 ruling may have several implications:

- Emphasis on Specific, Actionable Information: It underscores the legal importance for liability that any information conveyed to a psychiatrist about suicide risk, especially in remote settings, be highly specific, indicative of concrete actions or plans, and suggestive of immediacy for it to cross the threshold of "specific foreseeability."

- Judicial Caution in Outpatient Suicide Liability: The decision could reinforce a generally cautious approach by Japanese courts when assigning liability to psychiatrists for outpatient suicides, unless there is clear evidence that the physician possessed unambiguous information about an impending and preventable suicide attempt.

- Need for Protocols in Remote Care: The case highlights the critical need for robust protocols and clear communication strategies in the provision of remote psychiatric care, particularly concerning risk assessment, emergency contact procedures, and the delineation of responsibilities when family members are heavily involved.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 12, 2019, decision in the case of Patient A and Dr. Y clarifies that for a psychiatrist to be held legally responsible for an outpatient's suicide, the suicide must have been specifically foreseeable based on concrete and particularized information available to the physician. General awareness of a patient's diagnosis, past history of self-harm (especially if followed by recovery), or expressions of suicidal ideation, particularly when communicated indirectly and without accompanying reports of immediate preparatory actions, may not meet this high legal threshold. This ruling underscores the immense challenges and legal intricacies involved in managing suicide risk in psychiatric outpatients, especially when care is complicated by geographical distance, reliance on intermediaries, and the inherent unpredictability of severe mental illness. It emphasizes the critical role of precise communication and the difficulty of establishing liability in the absence of clearly foreseeable, imminent danger.