Relocation, Rights, and Reasonableness: Japan's Supreme Court on Employee Transfers (July 14, 1986)

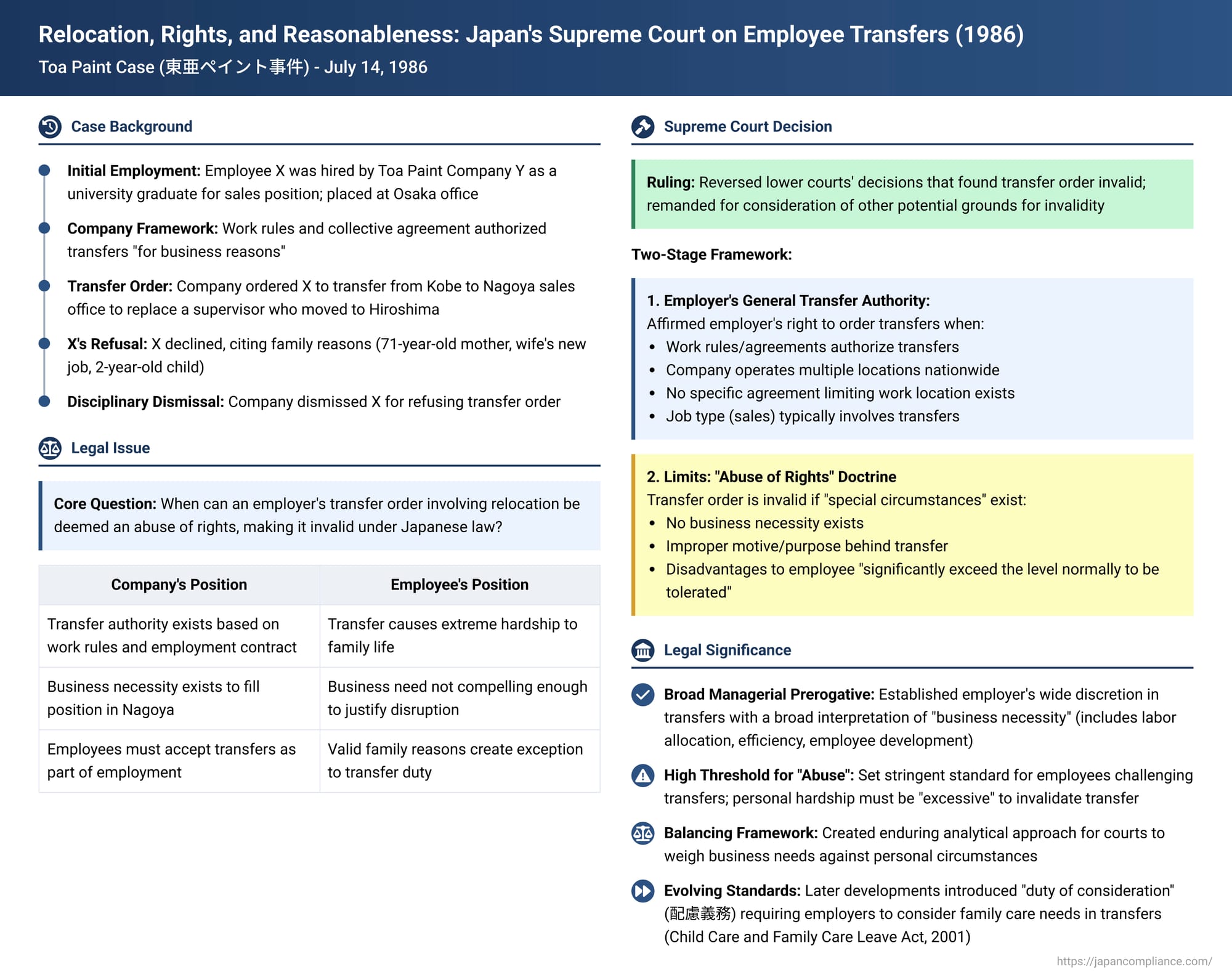

On July 14, 1986, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment in a case widely known as the "Toa Paint Case" (東亜ペイント事件). This ruling established foundational legal principles concerning an employer's authority to order employee reassignments (配置転換 - haichi tenkan), particularly transfers involving relocation (転勤 - tenkin), and defined the critical limits on this authority through the "abuse of rights" doctrine. While affirming a significant degree of managerial prerogative, the case also set the stage for ongoing judicial scrutiny of the balance between business needs and employee welfare.

The Disputed Transfer: Business Needs vs. Family Life

The plaintiff, X, was a university graduate hired by Defendant Company Y, a paint manufacturing and sales company with approximately 13 sales offices across Japan. X was employed in a sales capacity. Company Y's employment framework included:

- A collective bargaining agreement with its labor union, which stipulated: "The company may order union members to transfer or be reassigned for business reasons."

- Work rules stating: "The company may order employees to change assignments for business reasons. In such cases, refusal without a valid reason is not permitted."

It was common practice within Company Y for sales staff to be transferred between its various offices.

X was initially assigned to the company's Osaka office. After a period of secondment to another firm, X was working at Company Y's Kobe sales office. Importantly, at the time of X's initial hiring, there was no agreement limiting X's place of work to Osaka or any specific location.

The dispute arose from the following sequence of events:

- Initial Transfer Request (Hiroshima): Company Y identified a need to fill a vacant "Shunin" (主任 - a supervisory or senior staff position) role at its Hiroshima sales office. X, who held a Shunin status, was informally approached about this transfer. X declined, citing family circumstances that made relocation problematic.

- Revised Transfer Request (Nagoya): Consequently, Company Y assigned Supervisor A from its Nagoya sales office to the Hiroshima position. Soon after, Company Y informally asked X to transfer to the Nagoya sales office to fill the vacancy created by Supervisor A's move. X again refused, citing the same family reasons.

- Formal Transfer Order and Refusal: Despite X's refusals during these informal discussions, Company Y formally issued an order (the "Transfer Order") instructing X to transfer to the Nagoya sales office. X once again refused to comply with this formal order.

- Disciplinary Dismissal: As a result of X's refusal to obey the Transfer Order, Company Y subjected X to disciplinary dismissal, asserting that the refusal constituted a violation of its work rules and a valid ground for such disciplinary action.

Company Y's Business Needs and X's Personal Circumstances:

- The company did have an operational need to appoint a suitable replacement for Supervisor A in its Nagoya sales office. However, the lower courts found there was no absolute necessity for X specifically to be the one to fill this role; Company Y later transferred another employee, B, to the Nagoya position without any reported operational difficulties.

- At the time the Transfer Order was issued, X was living with his 71-year-old mother (whom he supported), his wife, who had recently commenced employment as a nursery school teacher at a newly established facility, and their 2-year-old daughter.

The Lower Courts: Transfer Deemed an Abuse of Rights

Both the Osaka District Court (first instance) and the Osaka High Court (on appeal) sided with Plaintiff X, finding the Transfer Order to be an abuse of managerial rights and therefore invalid. Their reasoning centered on the assessment that the business necessity for X's specific transfer to Nagoya was not overwhelmingly strong, especially since other employees could (and eventually did) fill the role. Against this moderate business need, they weighed the considerable hardship and disruption that relocation would impose on X's family life, particularly given his responsibilities towards his elderly mother and his wife's new employment. They concluded that X had valid reasons to refuse the transfer, rendering the subsequent dismissal unlawful. Company Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Framework for Transfer Orders

The Supreme Court partially overturned the High Court's decision. While the ultimate outcome involved remanding the case for consideration of other potential grounds of invalidity X might have raised, the Supreme Court's judgment laid down a highly influential two-stage framework for assessing the validity of transfer orders.

I. Establishing the Employer's General Right to Order Transfers

The Supreme Court first affirmed that, under the circumstances, Company Y did possess the general authority to order X's transfer:

- It noted the existing provisions in Company Y's collective agreement and work rules that explicitly permitted the company to order employee transfers for business reasons.

- It acknowledged Company Y's operational structure, with numerous sales offices nationwide, and its established practice of frequently transferring sales personnel between these locations.

- Crucially, it highlighted that X was hired as a university graduate for a sales role and, at the time of entering the employment contract, no agreement had been made to limit X's place of work to Osaka or any other specific location.

Based on these factors, the Court concluded: "Under these circumstances, Company Y should be considered to have the authority to determine X's place of work without individual consent and to order a transfer and demand the provision of labor there."

II. Defining the Limits: The Abuse of Rights Doctrine

Having established the employer's general right to order transfers, the Supreme Court then delineated the limitations on this right through the doctrine of abuse of rights (権利の濫用 - kenri no ranyō):

- "An employer, based on business necessity, should be able to determine a worker's place of work at its discretion. However, transfers, especially those involving relocation, generally cannot avoid significantly impacting a worker's personal life. Therefore, the employer's right to order transfers cannot be exercised without restriction, and it goes without saying that its abuse is not permissible."

- The Test for Abuse of Right: The Court stipulated that a transfer order would constitute an abuse of rights (and therefore be invalid) only if "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) exist. It identified three primary categories of such circumstances:

- Lack of Business Necessity: If "no business necessity for the said transfer order" exists.

- Improper Motive/Purpose: Even if business necessity is present, if "the transfer order was made with other unjust motives or purposes" (e.g., as a form of retaliation or to constructively dismiss the employee).

- Excessive Disadvantage to the Employee: If business necessity exists and there is no improper motive, but the transfer "imposes on the worker disadvantages significantly exceeding the level normally to be tolerated" with such a move.

- Defining "Business Necessity": The Supreme Court provided a relatively broad interpretation of what constitutes "business necessity" in this context: "Regarding the aforementioned business necessity, it is not appropriate to limit it to a high degree of necessity, such as the transfer being irreplaceable by any other person. As long as aspects contributing to the rational operation of the enterprise are recognized—such as appropriate allocation of labor force, improvement of operational efficiency, development of employee abilities, enhancement of work motivation, and facilitation of smooth business operations—the existence of business necessity should be affirmed."

III. Application to X's Case by the Supreme Court

Applying this framework to the facts as determined by the High Court, the Supreme Court reached a different conclusion regarding the abuse of rights:

- Business Necessity Found: "In this case, there was a necessity to transfer a suitable person as a replacement for Supervisor A in the Nagoya sales office. Therefore, selecting X, who was engaged in sales with Shunin status, and ordering X to work at the said sales office (the Transfer Order) can be said to have ample business necessity."

- Employee's Disadvantage Not Deemed "Excessive": "And, considering X's family situation as described, the disadvantages to X's family life caused by the transfer to the Nagoya sales office should be said to be of a degree normally to be tolerated with a transfer."

- Conclusion on Abuse of Rights: "Therefore, under the aforementioned factual circumstances, it is reasonable to conclude that the Transfer Order does not constitute an abuse of rights."

Because the Supreme Court found the High Court's reasoning on the abuse of rights to be flawed, it remanded the case for the High Court to consider any other arguments X might have made for the invalidity of the transfer order.

Deeper Analysis: The Toa Paint Framework and Its Evolution

The Toa Paint judgment has been a cornerstone of Japanese jurisprudence on employee reassignments for decades.

- Legal Basis for Transfer Power: The Supreme Court's affirmation of the employer's power to transfer (Point I) drew upon the existence of general provisions in work rules and collective agreements, alongside the absence of any specific agreement limiting X's work location. This approach, as noted by commentators, could accommodate both the "comprehensive consent theory" (where employees are seen as agreeing at hiring to broad managerial discretion over assignments) and the "labor contract theory" (where reassignments are permissible if within the agreed scope of the individual contract). In practice, for traditionally hired regular full-time employees in Japan, courts have rarely found explicit contractual limitations on work location or job duties.

- The High Bar for "Abuse of Rights": The criteria set by the Supreme Court for an abuse of rights, particularly the definition of "business necessity" and "disadvantages significantly exceeding the level normally to be tolerated," established a relatively high threshold for employees challenging transfer orders. Employers were granted considerable discretion, and subsequent Supreme Court cases (e.g., the Teikoku Zoki Seiyaku Case, 1999; Kenwood Case, 2000) further reinforced the strict interpretation, making it difficult for employees to successfully claim that personal hardship rendered a transfer an abuse of rights unless the circumstances were exceptionally severe (e.g., critical family care needs that only the employee could meet).

- The Evolving Role of "Employer's Duty of Consideration" (配慮義務 - hairyō gimu): More recent developments have introduced a nuanced element into the assessment. The Child Care and Family Care Leave Act was amended in 2001 to explicitly require employers to give consideration to a worker's child-rearing or family care situation when ordering transfers (Article 26). Additionally, the Labor Contract Act (Article 3, Paragraph 3) promotes the concept of work-life balance.

Reflecting these legislative and societal shifts, courts have increasingly begun to examine whether an employer has fulfilled this "duty of consideration" when evaluating the reasonableness of a transfer order. Failure to give adequate consideration to an employee's significant family responsibilities might now weigh more heavily in the abuse of rights analysis. Some case law suggests this duty of consideration might even extend to aspects of an employee's career development.

While this introduces a more robust balancing of interests, the commentary notes some academic concern about potential privacy infringements if employers delve too deeply into employees' personal lives to fulfill this duty, suggesting a need for clearer procedural guidelines, such as mandatory consultation. - Procedural Fairness: There is also growing attention, in both case law and academic discussion, to the procedural aspects of transfer orders, such as the adequacy of advance notice and the explanations provided to employees, particularly in light of the Labor Contract Act's emphasis on promoting understanding of contract terms (Article 4, Paragraph 1).

Conclusion: A Legacy of Managerial Prerogative Tempered by Evolving Considerations

The 1986 Toa Paint Supreme Court judgment solidified a framework that grants Japanese employers significant, though not unlimited, authority to transfer employees for legitimate business reasons. While the initial interpretation set a high bar for employees to challenge such orders based on personal hardship, the legal landscape has since evolved. The introduction of statutory duties for employers to consider employees' family care needs and the broader societal push for work-life balance have led courts to more closely scrutinize the "duty of consideration" in transfer decisions. Although the core principles of Toa Paint regarding business necessity and abuse of rights remain influential, their application today is increasingly tempered by these newer considerations, reflecting a gradual shift towards a more nuanced balancing of employer prerogatives and employee welfare in the context of workplace relocations. The commentary rightly suggests that given the significant changes in employment systems and societal values since 1986, a fundamental re-evaluation of the Toa Paint framework itself might be warranted.