Registered vs. Real Owner: 1960 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on New Share Allotments

Date of Judgment: September 15, 1960

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

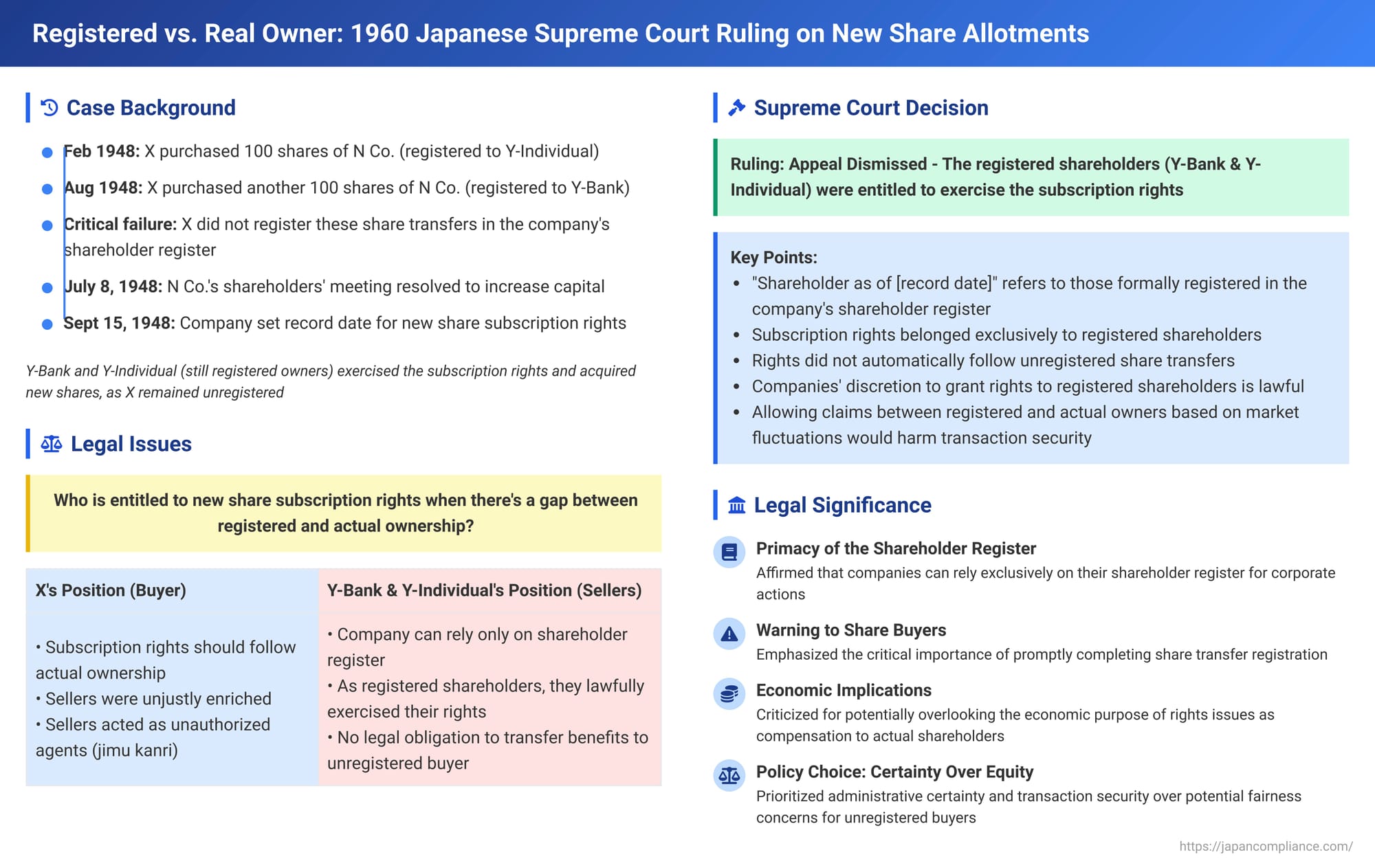

The transfer of shares in a company involves not only the agreement between buyer and seller and the delivery of share certificates (if issued) but also, crucially, the registration of this transfer in the company's shareholder register. Failure by the buyer to promptly update the register can lead to a disconnect between the "registered owner" (nominal owner) and the "substantive owner" (beneficial owner). This discrepancy becomes particularly problematic when the company undertakes corporate actions, such as issuing new shares through a rights offering. Who, in such a scenario, is entitled to subscribe to these new shares – the seller whose name still appears on the company's books, or the buyer who holds the share certificates but is not yet registered?

This complex issue was addressed by the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan in a significant decision on September 15, 1960. The case delved into the rights of an unregistered share purchaser when the company allotted new shares to shareholders of record as of a specific date, with the registered former owners exercising these rights.

The Legal Context of the Era: Pre-1950 Commercial Code

The legal framework governing corporations at the time of the underlying events (primarily the pre-1950s amendment Japanese Commercial Code) gave considerable leeway to companies and their shareholders' meetings in determining the specifics of new share issuances.

- Shareholder Resolutions Key for New Share Issues: Article 348 of the then Commercial Code stipulated that, unless otherwise provided in the company's articles of incorporation, the terms for granting new share subscription rights—including who was entitled and the content of those rights—were to be decided by a resolution of the shareholders' meeting.

- The Shareholder Register: The shareholder register (株主名簿 - kabunushi meibo) maintained by the company played a critical role. It was the primary record the company would consult to identify who it legally considered to be its shareholders for purposes of communication, dividend payments, and the allotment of rights.

Facts of the N Company Case

The dispute involved Mr. K.M. (hereinafter X), who purchased shares in N Co., and the registered sellers of those shares, Y-Bank and Y-Individual.

- Share Purchases and Failure to Register:

- In February 1948, X purchased 100 shares of N Co. through YS Securities. He received the share certificate, which was registered in the name of Y-Individual, along with a blank power of attorney to facilitate the name change.

- In August 1948, X purchased another 100 shares of N Co. through KS Securities, receiving the share certificate on August 6. This certificate was registered in the name of Y-Bank and had a blank endorsement.

- Crucially, X failed to complete the necessary procedures to have these share transfers registered in his name in N Co.'s shareholder register before key corporate actions took place.

- N Co.'s Rights Offerings:

- First (Second New Shares): On July 8, 1948, N Co.'s shareholders' meeting resolved to increase its capital. As part of this, subscription rights for "Second New Shares" were granted to "shareholders as of 4:00 PM on September 15, 1948," at a ratio of 1.4 new shares for each existing share, at a subscription price of 50 yen per share.

- Subsequent Offerings: N Co. conducted two further capital increases in 1949 (one resolved in January, another based on a corporate reorganization plan approved in July), again granting subscription rights to its shareholders as of specific record dates.

- Exercise of Rights by Registered Owners: Because X had not registered the transfers, Y-Bank and Y-Individual remained the shareholders of record for the shares X had purchased. Consequently, Y-Bank and Y-Individual exercised the subscription rights for the "Second New Shares" (each acquiring 140 shares) and also participated in the subsequent two rights offerings. This resulted in Y-Bank and Y-Individual acquiring a significant number of additional N Co. shares. (The PDF commentary notes Y1, one of the sellers, later sold some of these acquired shares ).

- X's Lawsuit: X sued Y-Bank and Y-Individual. He claimed that they had been unjustly enriched or had acted as an agent without authority (jimu kanri) by subscribing to the new shares. X demanded the transfer of these new shares to him in exchange for his payment of the subscription amounts, or, alternatively, monetary compensation for the difference between the market value of the new shares and their subscription price. (During the first instance court proceedings, X passed away, and his heirs continued the lawsuit ).

- The PDF commentary adds an interesting detail from X's appeal brief: X had also purchased N Co. shares from other individuals around the same time. After discovering his failure to register, he contacted all sellers. Unlike Y-Bank and Y-Individual, these other sellers either returned the subscription forms or renounced their rights, allowing X to subscribe to the new shares offered in respect of those holdings. This highlights that Y-Bank and Y-Individual took a different stance.

The lower courts dismissed X's claims.

The Supreme Court's Decision of September 15, 1960

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, upheld the lower courts' dismissal of X's appeal. Its reasoning was clear and firm:

Interpretation of "Shareholder as of [Date]"

The Court placed significant weight on the precise wording of N Co.'s shareholder resolution, which granted subscription rights to "shareholders as of 4:00 PM on September 15, 1948." It ruled that this phrase "unquestionably" referred to individuals whom the company could legally recognize and treat as shareholders at that specific time and date. This meant those persons who were formally registered in the company's shareholder register and were thereby able to assert their shareholder rights against the company. The substantive or beneficial ownership status of an unregistered party like X was deemed irrelevant for this determination.

Rights Belonged Exclusively to Registered Owners

As a direct consequence of this interpretation, the Supreme Court found that Y-Bank and Y-Individual, being the shareholders of record on the specified date, were the sole parties legally entitled to the new share subscription rights. They acquired the new shares "as their own right." Since X had failed to register the transfer of the original shares into his name by the record date, he did not acquire any subscription rights related to those shares.

Subscription Rights Did Not Automatically Follow Unregistered Share Transfers

The Court explicitly held that the specific new share subscription rights, which arose from a shareholders' meeting resolution under the then-Commercial Code, were concrete rights granted by the company. These rights did not automatically accompany the underlying shares when X purchased them from Y-Bank and Y-Individual, especially when X had not perfected his status vis-à-vis the company through registration.

Company's Lawful Discretion in Granting Rights

The Supreme Court noted that under the pre-1950 Commercial Code, the shareholders' meeting had the authority to decide the method by which new share subscription rights were granted to shareholders. Limiting these rights to shareholders registered as of a specific date and time was deemed a lawful exercise of this corporate discretion.

Concerns Regarding Good Faith and Transaction Security

Significantly, the Supreme Court explicitly endorsed a rationale from the first instance court (which the appellate court had affirmed) concerning the broader implications of such disputes. It stated that allowing the substantive (unregistered) owner and the nominal (registered) owner to make claims against each other based on subsequent market fluctuations in the value of new shares could disrupt the principle of good faith (shingisoku) and harm the security of transactions. This reflects a judicial policy preference for upholding the certainty of the shareholder register in corporate distributions, particularly to avoid complex and potentially opportunistic retrospective claims.

No Basis for Unjust Enrichment or Jimu Kanri

Given that Y-Bank and Y-Individual had lawfully exercised rights to which they were entitled as registered shareholders, the Court found no grounds for X's claims based on unjust enrichment or agency without authority (jimu kanri). The registered sellers had not profited from X's property or managed X's affairs; they had acted on their own registered entitlements.

Criticism and Analysis of the Decision

The Supreme Court's 1960 ruling, while providing legal certainty based on the shareholder register, has drawn criticism, as highlighted in academic commentary associated with this case:

- Ignoring Economic Realities of Rights Issues: A key criticism is that the decision arguably overlooked the economic purpose of many shareholder rights offerings. Such offerings, especially when new shares are priced at a discount to market value (here, 50 yen per share, likely par value), are often intended to compensate all existing shareholders (including substantive, unregistered owners) for the potential dilution of their holdings. By focusing strictly on the register, the Court may have sidestepped this compensatory aspect.

- Inconsistency with General Shareholder Register Interpretations: Some commentators argue that such a rigid adherence to the shareholder register for determining who receives subscription rights might be inconsistent with how the register's primacy is sometimes relaxed for other purposes, especially when there are no overriding administrative burdens on the company.

- Fairness to the Transferee (Buyer): The most pointed criticism concerns fairness. While the Court's aim to prevent opportunistic claims based on market fluctuations and to uphold transaction security is understandable, completely denying the unregistered buyer (X) any recourse could be seen as unduly harsh. The nominal sellers (Y-Bank and Y-Individual) effectively received a windfall: they had already sold the original shares to X (presumably at a price reflecting the shares' current value and future prospects, including potential rights offerings), yet they also reaped the benefits of the new share subscriptions. The subscription rights themselves had an inherent economic value, arguably paid for by X as part of the initial share purchase. Denying all of X's claims was viewed by some as excessive.

Implications of the Ruling

The Supreme Court's decision had clear implications:

- Emphasis on Prompt Registration: It powerfully underscored the critical importance for purchasers of shares to promptly complete the name change in the company's shareholder register. Failure to do so could result in the loss of significant economic rights attached to share ownership, such as the right to participate in new share allotments.

- Certainty for Companies: The ruling provided a degree of operational certainty for companies, allowing them to rely on their official shareholder register when conducting rights offerings and other corporate actions requiring shareholder identification.

Relevance in the Modern Era

Although the Japanese Commercial Code has undergone substantial revisions since 1950, eventually being replaced by the modern Companies Act, the fundamental issues raised by this case retain relevance:

- The Shareholder Register vs. Beneficial Ownership: The tension between the formal record of ownership (the shareholder register) and the reality of beneficial ownership (especially in cases of unregistered transfers) can still surface, particularly for shares of unlisted companies or those not held through centralized book-entry systems.

- Record Dates: Modern corporate practice universally uses "record dates" to determine shareholder entitlements for dividends, voting, and rights issues. This 1960 decision provides an early judicial endorsement of the principle that the company is entitled to deal with shareholders listed on its books as of such a date.

- Policy of Transaction Security: The Court's invocation of "transaction security" and "good faith" as policy reasons to limit claims between registered and unregistered parties remains a recurring theme in corporate and commercial jurisprudence.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1960 decision in the N Co. case established a firm precedent under the old Commercial Code, prioritizing the shareholder register for determining entitlements in shareholder rights offerings. It highlighted the risks faced by share purchasers who delay or neglect to register their ownership with the company. While the ruling provided certainty for corporate administration, it also sparked debate about the equitable distribution of rights between registered sellers and substantive (but unregistered) buyers, particularly concerning the economic value of subscription rights. The case serves as a historical reminder of the importance of diligent registration and the legal complexities that can arise when formal records diverge from underlying beneficial ownership.