Refund as Revenue? Japanese Supreme Court on Timing of Income from Corrected Overpayments in the Soei Sangyo Case

Date of Judgment: October 29, 1992

Case Name: Reassessment Disposition, etc. Invalidation Lawsuit (平成3年(行ツ)第171号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

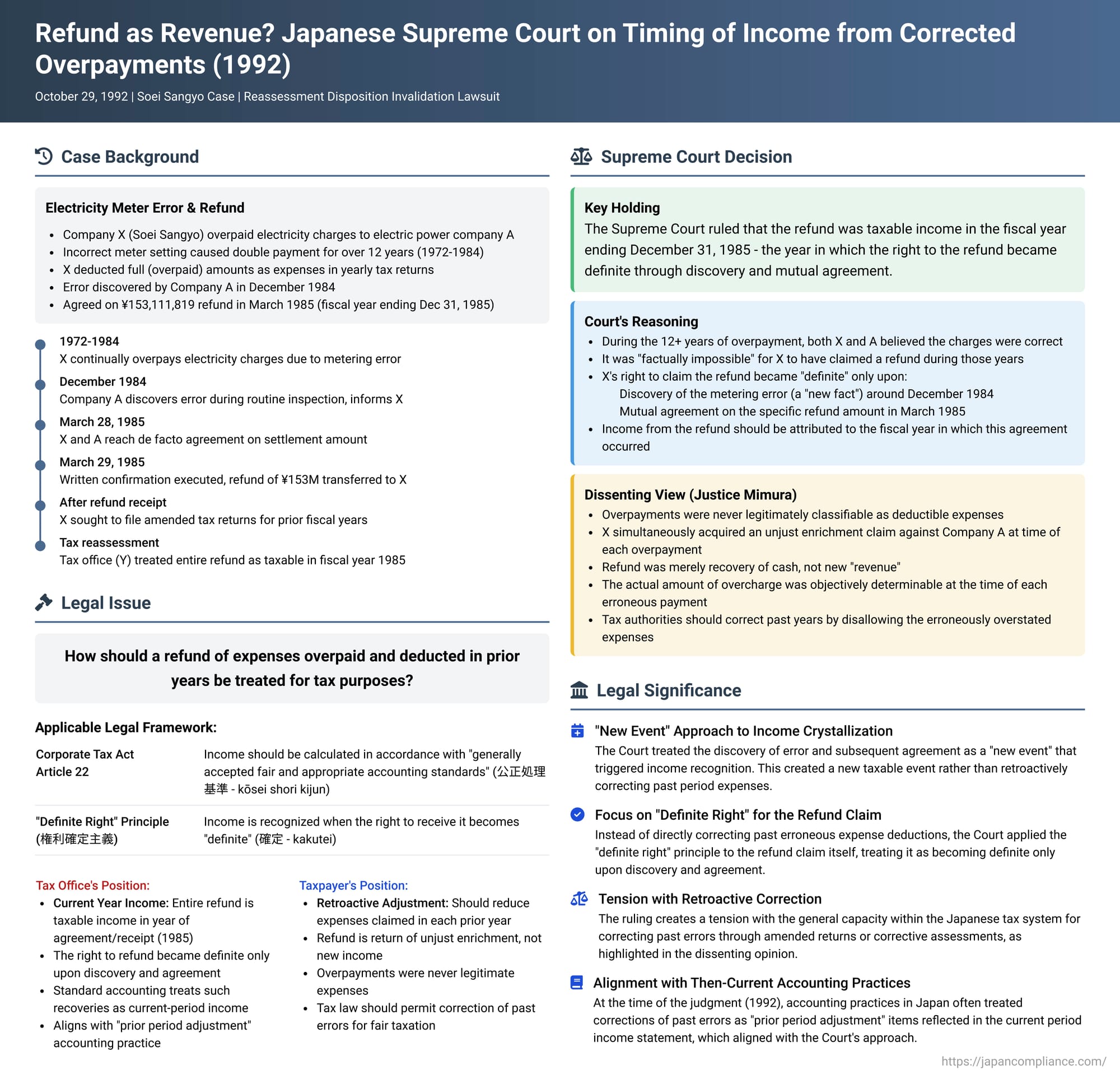

In a notable decision on October 29, 1992, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the complex issue of how a company should account for a refund of expenses that had been overpaid and deducted for tax purposes over many preceding years. The case, commonly known as the Soei Sangyo case, centered on whether such a refund should be recognized as income in the current fiscal year when the refund was agreed upon and received, or whether it necessitated a retroactive adjustment to reduce the expenses claimed in those prior years. The Court ultimately concluded that the refund constituted income in the year the right to receive it became definite through discovery and mutual agreement.

The Decade-Long Overpayment and the Refund Agreement

The appellant, X (formerly Soei Sangyo Co., Ltd.), was a company engaged in manufacturing automobile parts. X had a contract with an electric power company, A (formerly Tohoku Electric Power Co., Inc.), for the supply of electricity. Due to an incorrect setting of an electricity metering device at the time of a contract modification—an error that went unnoticed by both X and A for an extended period—X inadvertently overpaid its electricity charges by double the correct amount for over 12 years, from April 1972 to October 1984. Throughout these years, X had deducted the full (overpaid) amounts as electricity expenses in its corporate tax returns and had paid electricity tax based on these inflated figures.

Company A eventually discovered the metering error during a routine inspection around December 1984. On December 21, 1984, representatives from A informed X of the error, apologized, and explained that calculating the precise refund amount would be time-consuming due to the unavailability of old records for some of the earlier years. A proposed an estimated refund amount of over ¥200 million (which included interest) and also requested, for procedural simplicity, that X waive its right to a portion of the overpaid electricity tax. X agreed to these proposals.

Company A then proceeded to calculate the overcharges. For periods where detailed records were missing, A used the monthly average electricity consumption from the immediately following year for which records were available. For periods covered by "large power cards," those records were used, and for the most recent period before discovery, meter reading cards were available. Any contract penalty overcharges were calculated only for the periods where data was available.

Based on these calculations, on March 28, 1985, X and A reached a de facto agreement on the specifics of the settlement and the concrete refund amount. On March 29, 1985, they executed a written confirmation (確認書 - kakuninsho), and the agreed refund, totaling ¥153,111,819 for the overcharged electricity fees (plus interest and other adjustments), was transferred to X's designated bank account. This date of agreement and receipt fell within X's fiscal year ending December 31, 1985 ("the subject fiscal year").

For tax purposes, X sought to correct the past errors by filing amended tax returns for the prior fiscal years (at least those not barred by the statute of limitations) to reduce the electricity expenses it had originally claimed in each of those respective years. X also filed an amended return for "the subject fiscal year" (ending December 1985), presumably to reflect any net effect or related interest income from the settlement.

However, the head of the Y tax office (Sanjo Tax Office) took a different view. Y asserted that the entire refund amount received by X should be recognized as taxable income (ekikin) in "the subject fiscal year"—the year in which the agreement was finalized and the payment was received. Consequently, Y issued a corrective tax assessment and underpayment penalties for that fiscal year. After an unsuccessful administrative appeal, X challenged this tax assessment in court. The lower courts (Niigata District Court and Tokyo High Court) ruled against X, upholding the tax office's position. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Question: Current Income or Past Expense Adjustment?

The central legal issue was the proper timing for the tax recognition of the refunded electricity charges. Specifically, when a company receives a refund for expenses that were erroneously overpaid and deducted in multiple prior fiscal years, should this refund be treated as:

- Taxable income in the current fiscal year when the right to the refund becomes definite (e.g., upon discovery of the error and agreement on the refund amount) and the cash is received? Or,

- A retroactive adjustment that reduces the expenses originally claimed in each of those prior fiscal years, potentially leading to amended tax liabilities for those past years?

This determination hinged on the interpretation of Article 22 of the Corporate Tax Act, particularly the principles governing the timing of income (ekikin) recognition and the application of "generally accepted fair and appropriate accounting standards" (公正処理基準 - kōsei shori kijun).

X argued that the refund was essentially a return of unjust enrichment by A and should not be considered income in the current fiscal year. It asserted that tax law should permit retroactive correction of past errors to ensure fair taxation based on actual ability to pay. Y, the tax office, argued that the refund amount was definitively established by the agreement in the current fiscal year, and under standard accounting principles for ongoing businesses (like prior period adjustments), such a recovery of previously expensed items should be treated as income in the period it is finalized and received.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Refund is Income When Right to Receive is Fixed by Agreement

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the tax office's position that the refund was taxable income in "the subject fiscal year" (the year of agreement and receipt).

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Factual Impossibility of Earlier Claim: For the extended period of over 12 years (from April 1972 to October 1984), X had paid the electricity charges under the belief that they were correct. During this time, neither X nor even Company A had discovered the overcharges. Therefore, the Court found that it was "factually impossible" (jijitsujō fukanō de atta) for X to have claimed or received a refund for these overcharges during those past years.

- "Definite Right" to Refund Not Established in Past Years: Consequently, the Court held that it would not be appropriate to conclude that X's right to claim a refund for the overpaid electricity charges had become "definite" (kakutei) in each of those respective past fiscal years when the overpayments were made. Thus, a retroactive recalculation of income for those past years based on such a premise was not warranted.

- Right to Refund Crystallized by New Events and Agreement: Instead, the Supreme Court determined that X's right to claim the refund for the overcharged electricity fees became "definite" only when two key conditions were met:

- The discovery of the metering device misconfiguration by Company A around December 1984 (which the Court characterized as the occurrence of a "new fact").

- The subsequent mutual agreement reached between X and A on the specific amount to be refunded, as formalized by the written confirmation exchanged on March 29, 1985.

- Income Attribution to Year of Agreement: Therefore, the Court concluded that the income arising from the refund of these overcharges should be attributed to the fiscal year in which this agreement was reached—namely, "the subject fiscal year" ending December 31, 1985. The High Court's judgment to this effect was affirmed as correct.

The Dissenting View: Focus on Correcting Past Errors

One Justice, Mr. Mimura, issued a strong dissenting opinion. He argued that the majority's approach was flawed because:

- Overpayments Were Never Legitimate Expenses: The amounts X overpaid were never correctly classifiable as deductible costs or expenses under Article 22, paragraph 3 of the Corporate Tax Act in the first place. X's belief in their correctness at the time of payment did not alter their true nature.

- No Net Change in Assets at Time of Overpayment: When X overpaid electricity charges, it simultaneously acquired an unjust enrichment claim against Company A for the exact amount of the overpayment. Thus, while X's cash decreased, its assets (in the form of a claim receivable) increased by an equivalent amount, resulting in no net change in X's overall asset position at the moment of each overpayment. Therefore, the overpayment did not constitute a "loss" in those prior years.

- Refund as Recovery, Not New Revenue: The refund claim was merely a means to recover the cash previously lost through overpayment; its acquisition by X did not constitute new "revenue" under Article 22, paragraph 2.

- Objective Determinability of Overcharge: The actual amount of the overcharge was objectively fixed and, in principle, calculable at the time of each erroneous payment. The tax authorities should, therefore, investigate this objectively determined amount, irrespective of the later agreement between X and A, and correct the income for the past years by disallowing the erroneously overstated expense deductions. The agreement between X and A merely finalized the practical settlement of an already existing (though undiscovered) liability of A to X.

- Distinction from Disputed Rent Cases: The dissent distinguished this situation from cases involving disputed rent increases (like a prior Supreme Court case from Showa 53, which is case t67), where the amount of the claim itself is genuinely uncertain until a judgment or agreement is reached. In the Soei Sangyo case, the overcharge was, in theory, a knowable fact at all times, even if difficult to ascertain without discovering the meter error.

Analysis and Implications

The Supreme Court's majority decision in the Soei Sangyo case has several important implications for understanding revenue and expense recognition in Japanese corporate tax law:

- "New Event" Approach to Income Crystallization: The Court effectively treated the discovery of the long-standing error and the subsequent mutual agreement on the refund amount as a "new event". This new event, rather than the original erroneous payments, was deemed to be the point at which X's right to the refund became "definite" and thus gave rise to taxable income in the current period.

- Emphasis on "Definite Right" for the Refund Claim Itself: Instead of focusing on correcting past erroneous expense deductions, the Supreme Court applied the "definite right" principle (kenri kakutei shugi) to the refund claim that X acquired against Company A. This claim was held to have become definite and ascertainable only upon the agreement in the subject fiscal year.

- Tension with Retroactive Correction Principles in Tax Law: Legal commentary has noted a potential tension between this approach and the general capacity within the Japanese tax system for correcting past errors through amended returns (by the taxpayer) or corrective assessments (by the tax authorities). The dissenting opinion strongly favored such a retroactive correction of the originally overstated expenses. The majority's decision, however, leaned away from direct retroactive tax adjustments for X in this specific context, opting instead to treat the refund as current-year income.

- Alignment with (Then-Current) Accounting for Prior Period Adjustments: At the time of the judgment (1992), corporate accounting practices in Japan often treated corrections of past errors or unexpected recoveries relating to prior periods as "prior period adjustment" items, which would be reflected in the income statement of the current period rather than through a full restatement of past financial statements. The Supreme Court's decision to recognize the refund as income in the year of agreement aligns, at least in outcome, with this approach to current-period recognition.

- Impact of Later Changes in Accounting Standards: It is important to note, as highlighted by legal commentators, that Japanese accounting standards for error correction have evolved since this judgment. For example, ASBJ Statement No. 24, "Accounting Standard for Accounting Changes and Error Corrections" (issued in 2009), generally requires material errors in past financial statements to be corrected by retroactively restating those past statements, rather than just through a current-period adjustment. This evolution in accounting thought, which now more clearly treats such items as corrections of past period results rather than current period income/loss, might lead to different contextual discussions if a similar case arose today, though the Supreme Court's 1992 tax law interpretation would still stand as precedent unless revisited.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision in the Soei Sangyo case provides a significant interpretation regarding the timing of income recognition for refunds of expenses that were erroneously overpaid and deducted over many past years. By focusing on the point at which the right to the refund became definite—which the Court identified as the moment of discovery of the error and mutual agreement on the refund amount—the judgment favored treating the refund as taxable income in the current fiscal year. This approach prioritized the "new event" of agreement as the trigger for income realization for the refund claim itself, rather than mandating a direct retroactive unwinding of the prior years' expense deductions for tax purposes in this particular set of circumstances. The case underscores the complexities in aligning tax law with accounting principles, especially when dealing with the correction of long-standing errors, and highlights the critical role of when a right to income is deemed "definite" in the eyes of the law.