Reforming Japan's Family Law: Potential Impacts of Proposed Changes to Post-Divorce Child Custody and Support

TL;DR

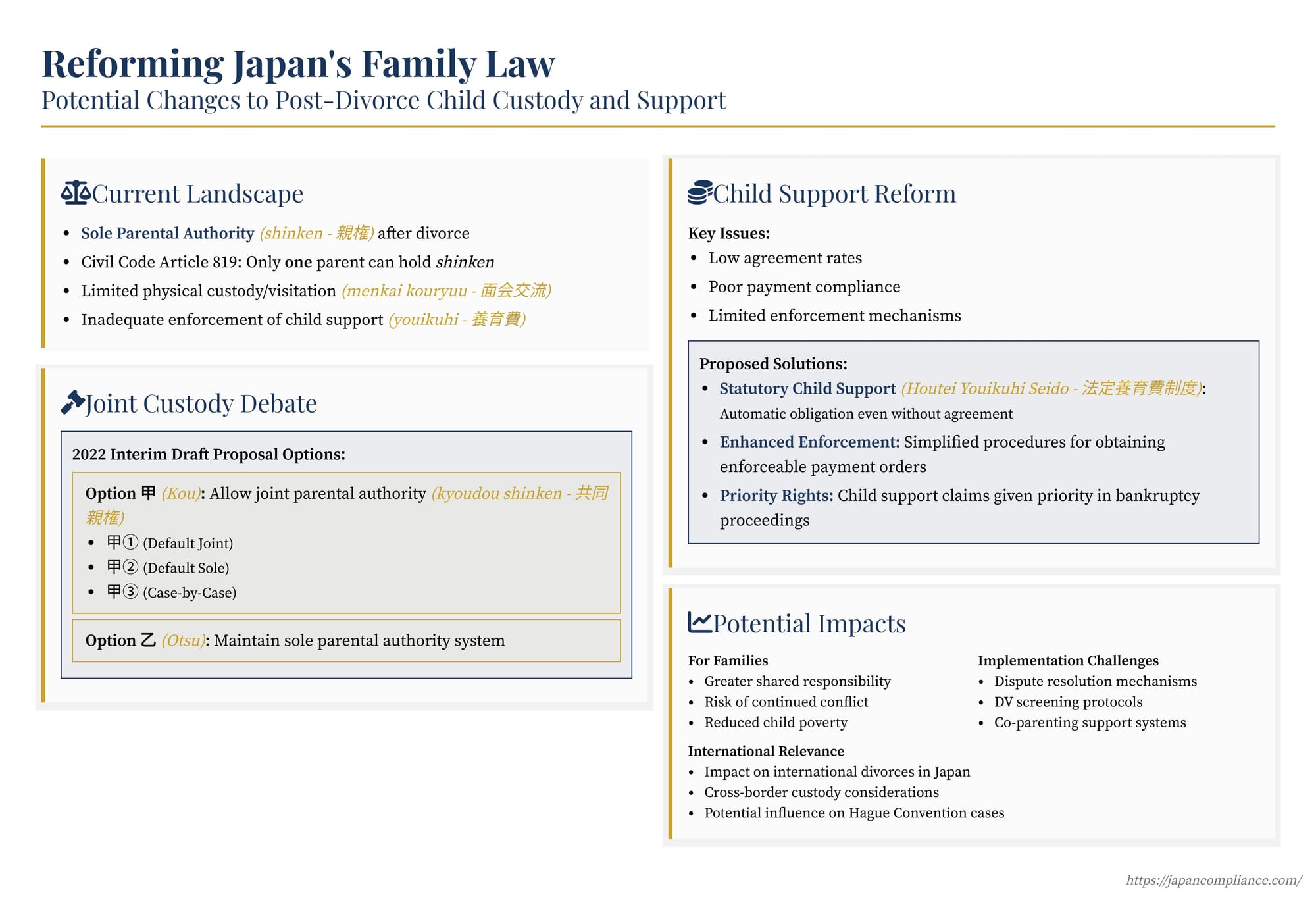

- A Ministry of Justice draft (Nov 2022) would allow joint parental authority after divorce, replacing Japan’s one-parent-only rule.

- Options range from default joint custody to case-by-case court selection; DV screening and dispute-resolution rules are still undecided.

- Separate proposals strengthen statutory child-support obligations and enforcement to combat child poverty.

Table of Contents

- Current Landscape: Sole Custody & Support Challenges

- 2022 Interim Draft: Aims and Principles

- Joint Custody Debate: Options 甲 / 乙

- Child-Support Reform: Statutory System & Enforcement

- Related Proposals (Visitation, Third-Party Roles)

- Potential Impacts for Families & Businesses

- Conclusion: A System in Flux

Japan is currently undertaking a significant review of its family law provisions concerning divorce (離婚 - rikon) and its consequences for children, potentially leading to the most substantial changes in decades. Central to the debate are fundamental shifts away from the long-standing principle of sole parental authority (親権 - shinken) after divorce towards potentially allowing joint custody, alongside efforts to strengthen the system for child support (養育費 - youikuhi). These proposed reforms, outlined in an Interim Draft Proposal (家族法改正中間試案 - Kazokuhou Kaisei Chuukan Shian) released by a Legislative Council (法制審議会 - Housei Shingikai) subcommittee of the Ministry of Justice in late 2022, reflect evolving societal views, international pressure, and a stated desire to prioritize the "best interests of the child" (子の最善の利益 - ko no saizen no rieki).

While these reforms are still under deliberation and subject to change, understanding the key proposals and the surrounding debate is crucial, not only for Japanese society but also for international residents, multinational families, and businesses employing staff in Japan, as the outcomes could significantly alter post-divorce realities.

The Current Landscape: Sole Custody and Child Support Challenges

Japan's current Civil Code (民法 - Minpou) operates on a principle of sole parental authority (shinken) after divorce. During marriage, parents exercise parental authority jointly (Article 818). However, upon divorce, the law requires parents to designate one parent as the holder of shinken (Article 819).

- Parental Authority (Shinken): This is a broad concept encompassing both rights and responsibilities related to the child's personal care and upbringing (身上監護 - shinjou kango) and the management of the child's property (財産管理 - zaisan kanri).

- Custody/Guardianship (Kangoken): While shinken usually includes the right to physical custody and day-to-day care (kangoken), the law technically allows for these to be separated, with one parent holding shinken and the other holding kangoken. However, in practice, the parent with shinken almost invariably also has physical custody.

- Visitation/Exchange (Menkai Kouryuu): The non-custodial parent generally has the right to visitation or "parent-child exchange" (面会交流 - menkai kouryuu), but arrangements are often based on parental agreement or court orders, and disputes are common, with visitation rates reported to be relatively low compared to some Western countries.

- Child Support (Youikuhi): Similarly, child support obligations exist, but payment relies heavily on parental agreements or court determinations. There is no robust state enforcement mechanism comparable to those in many US states or European countries. Agreement rates are low, many agreements are not formalized in enforceable ways (like notarial deeds), and payment rates are notoriously poor, contributing significantly to the high rate of poverty among single-mother households in Japan.

This system, particularly the default to sole shinken, has faced increasing criticism both domestically and internationally for potentially hindering the continued involvement of both parents in a child's life post-divorce and for failing to adequately secure financial support for children.

The 2022 Interim Draft Proposal: Aims and Core Principles

The Interim Draft Proposal, released in November 2022 for public comment, represents a major effort to address these issues. It doesn't present a single final plan but rather outlines various options and alternatives debated within the Legislative Council subcommittee, reflecting the complexity and contentiousness of the issues.

Key overarching themes and principles guiding the proposals include:

- Prioritizing the Child's Best Interests: Explicitly framing the reforms around ensuring the child's welfare and best interests, aligning with international norms like the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).

- Respecting the Child's Views: Incorporating mechanisms to consider the child's opinions (子の意見の考慮 - ko no iken no kouryo) in decisions affecting them, commensurate with their age and maturity.

- Promoting Continued Parental Involvement (where appropriate): Exploring ways to facilitate the ongoing involvement and responsibility of both parents in the child's upbringing after divorce, contrasting with the potentially exclusionary nature of the sole shinken system.

- Ensuring Child Support: Strengthening mechanisms for determining, agreeing upon, and enforcing child support payments to alleviate child poverty.

The Great Debate: Introducing Joint Custody (共同親権 - Kyoudou Shinken)?

The most fundamental and controversial aspect of the proposal is the potential move away from mandatory sole shinken post-divorce. The draft explores options for introducing or allowing joint parental authority (kyoudou shinken).

Arguments For Joint Custody:

Proponents, including some parent groups and legal experts, argue that allowing joint shinken could:

- Better reflect the reality of shared parenting during marriage and encourage continued co-parenting post-divorce.

- Reinforce the legal responsibility and rights of both parents towards their child.

- Potentially improve parent-child relationships, particularly with the non-custodial parent.

- Align Japan more closely with practices in many other developed nations.

- Address concerns about parental alienation or difficulties in maintaining contact under the sole shinken system.

Arguments Against and Concerns:

Opponents and skeptics, including DV support groups, women's rights advocates, and many legal practitioners, raise significant concerns:

- High-Conflict Cases: Implementing joint decision-making between parents who divorced due to high conflict could be impractical and detrimental to the child's well-being, potentially trapping the child in ongoing parental disputes.

- Domestic Violence (DV) and Abuse: A major concern is that joint shinken, even if primarily focused on legal authority rather than physical custody, could provide abusive ex-spouses with continued avenues for control, harassment, and unwanted contact, endangering the safety of the victim parent and child. Screening for DV and ensuring safety protocols would be critical but challenging.

- Decision-Making Paralysis: Requiring joint consent for important decisions (e.g., schooling, medical care, relocation) could lead to deadlock and delays, harming the child's interests, especially if parents cannot cooperate.

- Implementation Complexity: Defining the precise scope of rights and responsibilities under joint shinken versus physical custody (kangoken), establishing clear rules for resolving disputes, and determining primary residence and relocation rules would be highly complex.

The Proposal's Options:

Reflecting this deep division, the Interim Draft Proposal presented multiple options regarding post-divorce shinken:

- Option 甲 (Kou An): Allow Joint Shinken This option proposes introducing the possibility of joint parental authority after divorce.

- Option 乙 (Otsu An): Maintain Sole Shinken This option proposes retaining the current system where only one parent holds shinken after divorce.

Within Option 甲 (Allowing Joint Shinken), further variations were presented on how it would be implemented:

- 甲① (Default Joint): Joint shinken would be the default or preferred outcome, with sole shinken being exceptional.

- 甲② (Default Sole): Sole shinken would remain the default, but parents could opt for joint shinken by agreement or court order under certain conditions.

- 甲③ (Case-by-Case): No default principle; the court (or parents by agreement) would decide between joint or sole shinken based on the specific circumstances of each case, prioritizing the child's best interests.

The proposal also explored numerous sub-options regarding the practical exercise of joint shinken if adopted, covering issues like:

- Whether one parent must always be designated as the primary custodian (kangosha) (Option A vs. B).

- The scope of the designated custodian's unilateral decision-making power versus matters requiring joint consent (Options α, β, γ, detailing varying levels of required consultation or joint action).

- Rules governing the change of a child's residence (relocation), ranging from unilateral custodian decision (Option X) to requiring joint parental consent or court approval (Option Y, with further sub-options α, β, γ).

The sheer number of detailed options underscores the lack of consensus and the significant practical hurdles involved in shifting away from the established sole shinken system.

Reforming Child Support (養育費 - Youikuhi)

Addressing the inadequacy of child support payments is another central pillar of the reform proposals, driven by concerns about child poverty.

The Problem:

As noted, Japan faces challenges with low rates of child support agreements being made upon divorce, even lower rates of agreements being formalized in an easily enforceable manner (e.g., through a notarial deed), and poor compliance with payment obligations even when agreements or court orders exist.

Proposed Solutions:

The Interim Draft Proposal explores several avenues to improve this situation:

- Making Agreements a Condition for Amicable Divorce? One controversial option considered was making a formal agreement on child support (and potentially visitation) a prerequisite for finalizing an amicable divorce by mutual consent (協議離婚 - kyougi rikon).

- Pros: Would force parents to address these critical issues before dissolving the marriage.

- Cons: Could create a significant barrier to divorce, potentially trapping individuals (especially DV victims) in unwanted marriages; raises practical difficulties for municipal offices tasked with verifying the existence and adequacy of such agreements when accepting divorce registrations. Exceptions for cases involving DV or inability to negotiate were contemplated but add complexity.

- Statutory Child Support System (法定養育費制度 - Houtei Youikuhi Seido): A potentially more impactful proposal is the creation of a system where a basic child support obligation would arise automatically upon divorce, even in the absence of a specific agreement or court order.

- Concept: If certain conditions are met (e.g., based on parental income and number of children), a default minimum or standard amount of child support would become legally payable for a defined period.

- Debate Points: Key questions remain, as highlighted in the proposal discussions:

- Amount: Should it be a bare minimum subsistence level, or a standard amount calculated based on typical parental incomes (perhaps using existing court guidelines)? Concerns exist that a minimum might discourage negotiation for higher amounts where appropriate, or that a standard amount might be unduly burdensome for low-income obligors.

- Duration: For how long would this statutory obligation apply?

- Interaction with Agreements: How would it interact with voluntary agreements or court orders?

- Strengthening Enforcement Mechanisms: The proposal also includes measures aimed at making existing support obligations easier to enforce:

- Easier Enforcement Titles: Creating simplified procedures to obtain an enforceable title (債務名義 - saimu meigi) for child support, potentially bypassing lengthy court proceedings if an initial agreement exists.

- Priority Rights: Granting child support claims the status of a general statutory lien (一般先取特権 - ippan sakidori tokken), giving them priority over certain other debts of the obligor in bankruptcy or enforcement scenarios.

Other Related Proposals

Beyond custody and support, the draft touches on related areas:

- Parent-Child Exchange Procedures: Suggestions to improve court procedures for establishing and facilitating visitation, possibly including new types of interim orders or earlier involvement of Family Court Investigation Officers (家庭裁判所調査官 - katei saibansho chousakan) to observe interactions.

- Third-Party Roles: Discussions on potentially clarifying the rights and procedures for third parties, such as grandparents who have been significantly involved in a child's care, to seek custody or exchange under specific, limited circumstances.

Potential Impacts and Considerations

The proposed reforms, if enacted, could have far-reaching consequences:

- Impact on Families: The shift towards potentially allowing joint custody represents a profound change. It could foster greater post-divorce cooperation and shared responsibility for some families. For others, particularly those marked by conflict or abuse, it could exacerbate tensions and pose risks. The effectiveness hinges heavily on implementation details and support systems. Improved child support determination and enforcement hold significant potential for reducing child poverty.

- Implementation Hurdles: Successfully implementing joint custody, if adopted, would require substantial resources and careful design. Clear rules for decision-making, dispute resolution mechanisms (mediation, specialized court procedures), robust DV screening, and support services for co-parenting would be essential but are currently underdeveloped in Japan.

- Relevance for International Community / Businesses: These domestic law changes have implications beyond Japan's borders:

- Expatriates and International Families: Foreign nationals divorcing in Japan, or dealing with cross-border custody and support issues involving children residing in Japan, would be directly affected. A potential move to joint custody norms would alter the legal landscape they navigate. New child support rules could impact financial obligations.

- International Child Abduction (Hague Convention): While the primary focus is domestic, fundamental changes to custody law could potentially influence how Japanese courts approach international child custody disputes under the Hague Convention, although the direct link is complex.

- Corporate HR and Support: Companies employing staff in Japan (both Japanese nationals and expats) may need to update internal resources, employee assistance programs, or guidance related to family law issues to reflect any significant legal changes.

Conclusion: A System in Flux

The review of Japan's family law concerning post-divorce arrangements for children signifies a potential turning point. The Interim Draft Proposal from 2022 laid bare the deep societal divisions and complex practicalities surrounding issues like joint parental authority and child support enforcement. While the overarching goal is framed around the "best interests of the child," the path forward remains uncertain, with multiple competing options presented for key reforms.

The debate over joint versus sole custody is particularly significant, carrying the potential to fundamentally reshape parental rights and responsibilities after divorce. Simultaneously, proposals aimed at ensuring more reliable child support reflect a growing recognition of the economic hardships faced by many single-parent families.

As deliberations continue within the Legislative Council and broader society, the final form of any legislative changes remains to be seen. However, the direction of the discussion clearly indicates a move towards potentially greater shared parental responsibility and a stronger emphasis on securing financial support for children. For families, legal professionals, and businesses connected to Japan, monitoring these developments is essential, as the outcome could significantly impact the legal and social landscape for separated families in the years to come.