Recovering Inheritance in Japan: Supreme Court Redefines "Apparent Heir" and Limits Controversial Statute of Limitations

Decision Date: December 20, 1978

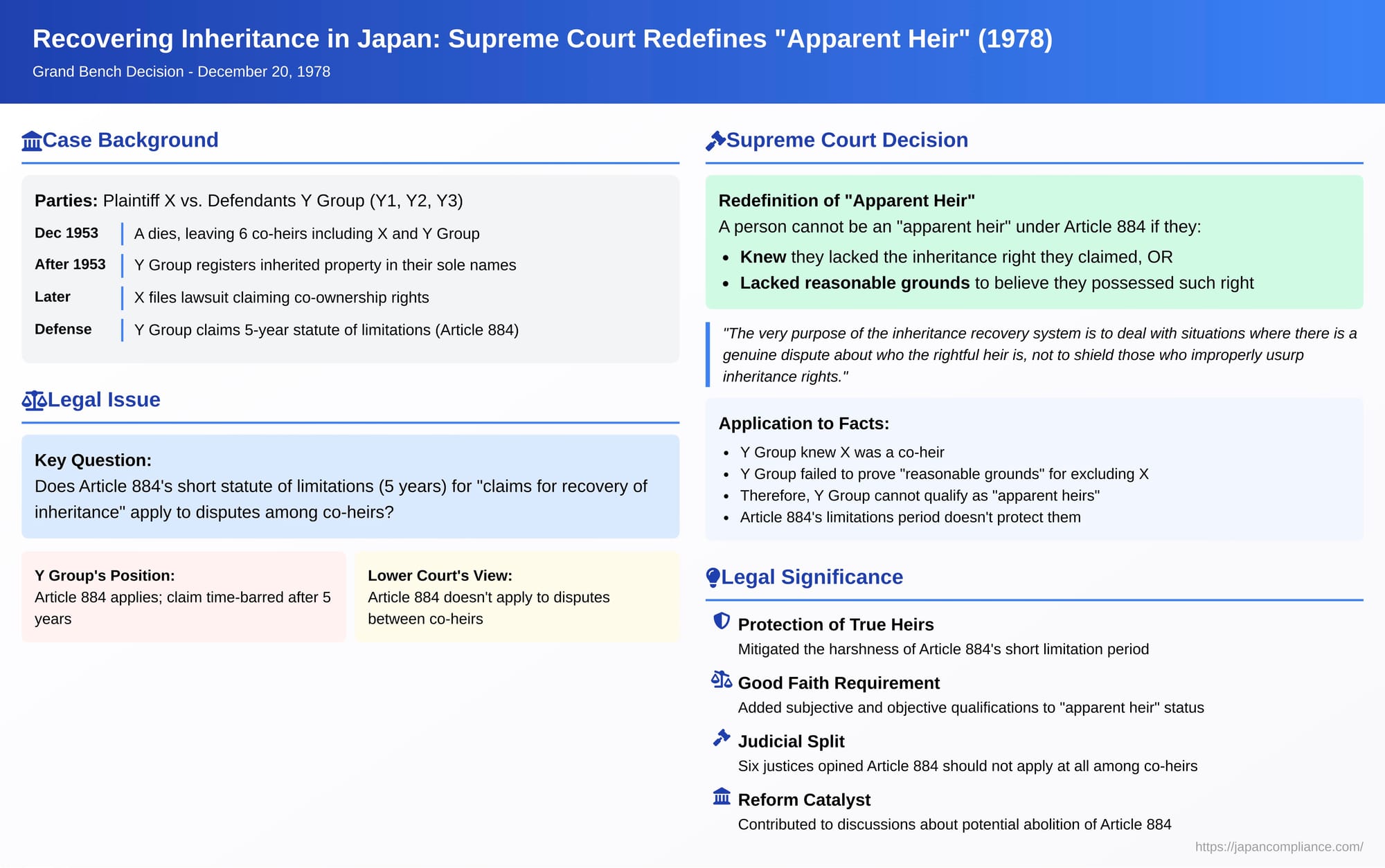

In a landmark Grand Bench decision on December 20, 1978, the Supreme Court of Japan significantly reinterpreted the scope and application of Article 884 of the Civil Code, which provides a relatively short statute of limitations for "claims for recovery of inheritance" (sōzoku kaifuku seikyūken). The ruling addressed whether this provision applies to disputes among co-heirs and, crucially, narrowed the definition of an "apparent heir" (hyōken sōzokunin) who could benefit from this limitations period, thereby impacting how inheritance disputes are resolved in Japan.

I. The Factual Context: A Co-heir's Challenge to Sole Registrations

The case arose from the estate of A, who passed away on December 15, 1953. His estate was to be inherited by six co-heirs, including the plaintiff X and the defendants Y1, Y2, and Y3 (referred to collectively as the "Y Group"). Following A's death, members of the Y Group registered several real properties, which were part of A's estate, into their respective sole names, based on inheritance.

X, asserting their own co-ownership rights derived from inheritance, filed a lawsuit against the Y Group. X demanded, among other things, the cancellation of the sole ownership registrations made by the Y Group to reflect X's rightful share in the properties.

The Y Group defended against X's claim by arguing that it was, in substance, a "claim for recovery of inheritance". As such, they contended it was time-barred by Article 884 of the Civil Code, which (at the time) stipulated that such a claim would be extinguished if not exercised within five years from the time the true heir became aware of the infringement of their inheritance rights, or in any event, within twenty years from the commencement of inheritance. The Y Group asserted that five years had passed since X became aware of their sole ownership registrations.

II. The Lower Court's Stance

The appellate court had rejected the Y Group's statute of limitations defense. Its reasoning was that a claim by one co-heir against another co-heir for the restoration of their co-ownership rights in inherited property, particularly as a preliminary step towards the division of the estate, does not constitute a "claim for recovery of inheritance" to which Article 884 applies. The appellate court partially granted X's claim, ordering a correction of the property registrations to show X's co-ownership share. Dissatisfied, the Y Group appealed to the Supreme Court.

III. The Supreme Court's Grand Bench Judgment: A Nuanced Interpretation

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench, while ultimately dismissing the Y Group's appeal and upholding the lower court's conclusion, did so based on significantly different reasoning regarding the application of Article 884 and the definition of an "apparent heir".

A. Applicability of Article 884 Among Co-Heirs

The Court first addressed whether Article 884 could apply to disputes between co-heirs. Departing from the appellate court's rationale, the majority opinion held that Article 884 can indeed apply in such situations.

The Court reasoned that if one or more co-heirs claim and manage a portion of the inherited property that exceeds their rightful inheritable share, effectively denying the rights of other true co-heirs to that excess portion, they are acting as "apparent heirs" for that specific excess portion. In such instances, there is no compelling reason to exclude the application of Article 884 solely because the dispute is among individuals who are all, to some extent, co-heirs.

The Court cited several grounds for this:

- Historical continuity with pre-revision inheritance law, which was understood to apply to disputes among co-heirs.

- The theoretical argument that a co-heir claiming an excess share is, concerning that excess, no different from a non-heir wrongly claiming inheritance rights.

- The practical need to stabilize legal relations and resolve disputes over inheritance rights in a timely manner, even among co-heirs, particularly for the protection of third parties who might transact with an apparent heir.

B. Redefining the "Apparent Heir" for Article 884 Purposes

This was the most critical part of the judgment. The Supreme Court significantly narrowed the definition of who could qualify as an "apparent heir" and thereby benefit from the short statute of limitations provided by Article 884.

The Court ruled that a person (including a co-heir with respect to a share exceeding their own) who claims inheritance rights is not to be considered an "apparent heir" for the purposes of Article 884 if they:

- Knew they did not possess the inheritance right (or the right to the excess share) they were claiming, yet still asserted themselves as an heir to that extent.

- Lacked reasonable grounds to believe they possessed such an inheritance right (or the right to the excess share), yet still asserted themselves as an heir to that extent.

The Court reasoned that individuals who assert inheritance claims in bad faith (knowing they have no right) or without any reasonable basis for their belief are not the intended beneficiaries of the special protection afforded by Article 884's short limitation period. Such individuals are, in substance, acting as ordinary wrongful possessors or infringers of property rights, and the policy of rapidly stabilizing legal relationships around an "apparent" (but false) state of inheritance does not extend to protecting them. The Court stated that the very purpose of the inheritance recovery system is to deal with situations where there is a genuine dispute about who the rightful heir is, not to shield those who improperly usurp inheritance rights.

C. Application to the Facts of the Case

Applying this newly articulated test to the Y Group, the Supreme Court found:

- It was clear that the Y Group knew X was also a co-heir at the time they registered the properties in their respective sole names.

- Crucially, the Y Group had failed to allege or prove any "reasonable grounds" that would justify a belief on their part that only they were entitled to the portions of the property exceeding their actual inheritable shares, to the exclusion of X.

Therefore, the Y Group did not meet the criteria to be considered "apparent heirs" entitled to invoke the Article 884 statute of limitations against X's claim.

D. Outcome

Although the Supreme Court disagreed with the appellate court's primary reasoning for not applying Article 884, it found that the appellate court's ultimate conclusion—rejecting the Y Group's statute of limitations defense and granting X's claim in part—was correct in its outcome. The appeal was dismissed.

IV. Analysis and Enduring Significance

This 1978 Grand Bench decision is a cornerstone in Japanese inheritance law, particularly for its impact on the controversial Article 884.

A. A Move to Protect True Heirs

The ruling is widely seen as an attempt to mitigate the harshness of Article 884's short statute of limitations, which could otherwise lead to true heirs quickly losing their inheritance rights to those who wrongfully claim them. By imposing stringent conditions (good faith and reasonable grounds) on who can be considered an "apparent heir," the Court significantly limited the circumstances under which the short limitation period could be successfully invoked.

B. The "Apparent Heir": From Objective Appearance to a Qualified Status

Prior to this decision, the concept of an "apparent heir" might have been understood more in terms of someone who objectively appeared to be an heir (e.g., through possession of property, registration). This ruling added crucial subjective and objective qualifications: the person claiming to be an apparent heir must not only outwardly appear as such but must also genuinely believe in their right (or at least not know otherwise) and have a reasonable basis for that belief. The PDF commentary suggests this introduction of good faith/reasonable grounds requirements was a key development.

C. "Reasonable Grounds": Interpretation and Burden of Proof

The judgment provided an example of "reasonable grounds," such as when a person is the sole heir listed in the official family register, and the existence of other co-heirs (e.g., an unacknowledged child) is not apparent. The PDF commentary notes that the concept of "reasonable grounds" bears similarity to criteria for "independent possession" in cases of acquisitive prescription. A subsequent Supreme Court case (July 19, 1999) clarified that the burden of proving the existence of such reasonable grounds (and their good faith) lies with the person invoking the Article 884 statute of limitations.

D. The Debate: Does This "Kill" Article 884?

The practical effect of this ruling was significant. As the PDF commentary indicates, some legal scholars opined that these stringent requirements for qualifying as an "apparent heir" would make it very rare for Article 884's short statute of limitations to be successfully applied, effectively rendering the provision a "dead letter" in many common scenarios, especially among co-heirs who are usually aware of each other's existence. The majority opinion itself acknowledged that disputes among co-heirs would likely fall under Article 884 only in "special cases".

However, the alternative opinions within the judgment (and some scholarly views) argued that there would still be a non-negligible number of situations where Article 884 could apply, such as when a co-heir genuinely and with reasonable cause does not know about the existence of other co-heirs (e.g., an unacknowledged illegitimate child, or heirs from a previous marriage unknown to current family members).

E. Alternative Judicial Opinions in the Same Case

The Grand Bench was not unanimous in its core reasoning.

- A significant minority of six justices opined that Article 884 should not apply at all to disputes among co-heirs. Their view prioritized the principles of fair and equitable division of inherited property among all true co-heirs, arguing that the short statute of limitations was incompatible with this goal and that co-heirs' rights should be resolved through the process of estate division (isan bunkatsu), which itself has no strict time limit for initiation. They contended that applying Article 884 among co-heirs could unfairly benefit a co-heir who improperly seizes property, at the expense of others.

- Other supplementary opinions debated the majority's introduction of good faith/reasonable grounds criteria into the application of a statute of limitations, noting its departure from general principles where the defendant's state of mind is usually irrelevant to the running of time periods. Some justices in their supplementary opinions sought to further explain or justify the majority's approach, for example, by linking the special nature of the inheritance recovery claim's statute of limitations to having an effect similar to acquisitive prescription.

F. Theoretical Underpinnings: Independent Right vs. Aggregate of Rights

The PDF commentary alludes to an ongoing theoretical debate about the nature of the "claim for recovery of inheritance": is it a unique, independent right specifically created by the Civil Code, or merely a collective term for various individual rights (like property claims, restitution claims) that a true heir can exercise to recover their inheritance?. While this 1978 ruling didn't definitively settle that theoretical debate, by focusing on the character and qualifications of the defendant (the "apparent heir"), it profoundly impacted the practical application of Article 884's statute of limitations, regardless of which theory one subscribes to concerning the claimant's right.

G. The Evolving Landscape: Article 884 and Future Reforms

The PDF commentary notes that the difficulties and controversies surrounding Article 884, including those highlighted by this case, have led to discussions about its potential abolition or reform, particularly in the context of addressing broader societal issues like "ownerless land" that can arise from unresolved, long-standing co-ownership of inherited property. The suggestion to delete Article 884, aiming for clearer rules on acquisitive prescription of inherited property, indicates a potential shift in legal policy thinking towards prioritizing efficient property use and clearer title over the specific (and often criticized) mechanism of Article 884.

V. Conclusion: A Balancing Act with Lasting Impact

The Supreme Court's 1978 Grand Bench decision on claims for recovery of inheritance represents a critical effort to balance the policy of quickly stabilizing inheritance-related legal statuses with the need to protect the substantive rights of true heirs, especially against those who improperly claim inheritance. While affirming that Article 884's statute of limitations could theoretically apply among co-heirs, the Court's stringent redefinition of the "apparent heir" who could benefit from this short period significantly curtailed its practical reach. This ruling remains a pivotal interpretation of a difficult area of Japanese inheritance law, illustrating the judiciary's role in shaping legal principles to achieve more equitable outcomes within the statutory framework.