Recommendation or Ruling? Japanese Supreme Court on the 'Dispositivity' of Hospital Bed Reduction Advice

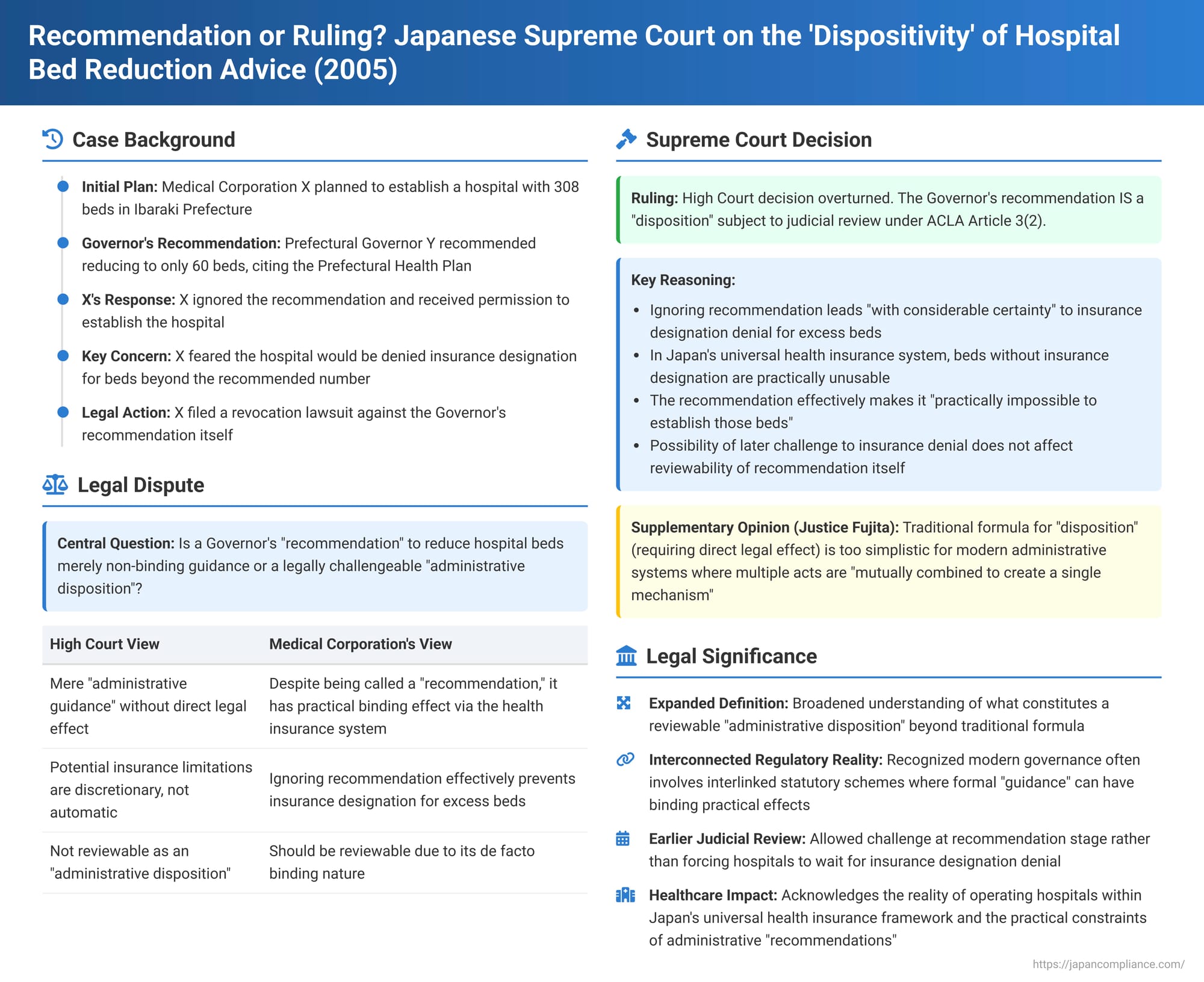

In Japan's highly regulated healthcare sector, prefectural governors play a significant role in healthcare planning, including efforts to control the number of hospital beds within specific regions. But what happens when a governor issues a "recommendation" to a hospital planning to open or expand, advising it to reduce its proposed number of beds? Is this merely non-binding advice, or can it be considered a formal "administrative disposition" that can be legally challenged in court? The Supreme Court of Japan tackled this crucial question in a judgment on October 25, 2005 (Heisei 15 (Gyo-Hi) No. 320).

The Hospital Plan and the Governor's "Recommendation"

The case involved Medical Corporation X, which planned to establish a new hospital with 308 beds in Tsuchiura City, Ibaraki Prefecture. X duly applied to the Ibaraki Prefectural Governor, Y, for the necessary permission under Article 7, Paragraph 1 of the Medical Act (pre-amendment version).

In response, Governor Y, acting under Article 30-7 of the Medical Act (a provision now found in Article 30-11 of the current Act), issued a formal "recommendation" (kankoku) to Medical Corporation X. This recommendation advised X to reduce its planned bed count from 308 to 60. The governor's rationale was that establishing a hospital with 308 beds would cause the total number of beds in the Tsuchiura healthcare zone to exceed the "necessary bed count" stipulated in the Ibaraki Prefectural Health and Medical Care Plan.

Medical Corporation X did not agree with or follow this recommendation. Subsequently, Governor Y did grant X permission to open the hospital. However, X was concerned about the implications of ignoring the recommendation, specifically arguing that it would prevent the hospital from obtaining designation as an "insurance medical care institution" from the health insurance authorities for all 308 beds (under the then-applicable Health Insurance Act Article 43-3, Paragraph 4, now Article 65, Paragraph 4). Being unable to treat patients under Japan's universal health insurance system for a significant portion of its beds would render those beds practically unusable. Thus, X filed a lawsuit seeking the revocation of the governor's recommendation itself, contending it was illegal.

The High Court's View: Just "Guidance," Not a "Disposition"

The Tokyo High Court, acting as the appellate court, dismissed Medical Corporation X's lawsuit. It held that the governor's recommendation under Medical Act Article 30-7 was merely "administrative guidance" (gyōsei shidō). The High Court reasoned that the recommendation did not directly create or alter X's legal rights or obligations. While acknowledging that the Health Insurance Act allowed authorities to restrict the number of beds designated for insurance coverage if such a recommendation was ignored, it noted that the authorities had discretion in this matter; non-compliance did not automatically and legally lead to such a restriction. Therefore, the High Court concluded that the recommendation did not qualify as an "administrative disposition or other act of public authority" under Article 3, Paragraph 2 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA), which is a prerequisite for filing a revocation lawsuit.

The Supreme Court's Verdict (October 25, 2005): Recommendation as a Reviewable "Disposition"

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case, finding that the governor's recommendation did indeed qualify as an administrative disposition subject to judicial review.

The Court's reasoning focused on the practical and highly probable consequences of ignoring such a recommendation:

- The "De Facto Coercion" Effect: The Supreme Court acknowledged that while the Medical Act frames such recommendations as administrative guidance expecting voluntary compliance, the reality is different. The Court stated that a recommendation to reduce hospital bed numbers, if not followed, leads with "a considerable degree of certainty" to a specific adverse outcome: the hospital, even if permitted to open, will only receive designation as an insurance medical care institution for the reduced number of beds (i.e., the 60 beds recommended, not the 308 planned).

- The Indispensable Role of Insurance Designation: "In our country, where a so-called universal health insurance system is adopted, there are hardly any patients who consult hospitals without using health insurance, national health insurance, etc., and it is a publicly known fact that almost no hospitals operate without being designated as insurance medical care institutions." Therefore, being unable to obtain insurance designation for the beds beyond the recommended number effectively means "it becomes practically impossible to establish those beds."

- Conclusion on "Dispositivity": "Considering together such effects of the recommendation... on the designation of insurance medical care institutions and the significance that such designation holds in hospital management," the Supreme Court concluded that "it is appropriate to interpret this recommendation as falling under an 'administrative disposition or other act of public authority' as referred to in Article 3, Paragraph 2 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act."

- Availability of Later Remedies Not a Bar: The Court also stated that the possibility of challenging a subsequent refusal of insurance designation in a separate lawsuit "does not affect the aforementioned conclusion" that the initial recommendation itself is a reviewable disposition. This allows for an earlier challenge to the core issue.

Broader Implications: Beyond the "Traditional Formula" for Dispositions

This decision, and a similar one by the Second Petty Bench three months prior (July 15, 2005, concerning a hospital closure recommendation ), signaled a more pragmatic approach by the Supreme Court to what constitutes a reviewable administrative act.

Justice Hisashi Fujita, in a supplementary opinion to this judgment, provided insightful commentary on this evolution. He noted that the "traditional formula" for defining an administrative disposition (generally requiring an act that directly and legally forms or determines the rights and duties of citizens) might be too simplistic for the complexities of modern governance. He observed that contemporary administrative bodies often employ a range of tools, including administrative guidance and other non-legally binding acts, which are "mutually combined to create a single mechanism (system)". Within such mechanisms, individual acts, like the recommendation in this case, can acquire "new meaning and function" that are not apparent when viewed in isolation. The traditional formula, he suggested, "is not necessarily premised on such facts" and was therefore "not appropriate" for direct application in this instance.

The significance of this Supreme Court judgment, as highlighted by legal commentators, is its willingness to look beyond the formal legal nature of an act (as mere "guidance") and consider its predictable, substantial, and adverse practical consequences within a linked regulatory system. It allows for judicial review at an earlier, more effective stage.

Significance of the Ruling for Healthcare Providers

This ruling has important implications for healthcare providers in Japan:

- It provides an avenue for hospitals and medical corporations to legally challenge bed number reduction recommendations issued by prefectural governors at the recommendation stage itself, rather than having to go through the entire process of establishing a hospital (potentially with more beds than recommended) and then facing a likely partial refusal of insurance designation.

- The decision acknowledges the strong, almost deterministic, link between such recommendations under the Medical Act and the subsequent decisions on insurance medical care institution designation under the Health Insurance Act, recognizing the realities of operating a hospital within Japan's universal health insurance framework.

What Happened on Remand?

It is worth noting, as pointed out in the provided commentary, that after the Supreme Court remanded this case for a hearing on the merits, both the Mito District Court (October 24, 2007) and the Tokyo High Court (May 14, 2008) ultimately dismissed Medical Corporation X's claim to revoke the recommendation. This means that while the Supreme Court found the recommendation to be a reviewable "disposition," the lower courts, upon examining the substance, found the governor's recommendation itself to be lawful.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's 2005 decision in the Ibaraki hospital bed case represents a significant development in Japanese administrative law. It affirmed that an administrative "recommendation," which may formally appear as non-binding guidance, can indeed be treated as a reviewable "disposition" if it is foreseeably linked to substantial adverse consequences for the recipient within a broader regulatory scheme. By recognizing the practical impact of such recommendations on the viability of hospital operations under the universal health insurance system, the Court expanded the scope for judicial review, allowing for earlier and potentially more effective challenges to administrative actions that, while not directly imposing legal obligations, exert powerful de facto constraints.