Reasons for Tax Reassessment: Japanese Supreme Court on Blue Form Returns and Asset Characterization

Date of Judgment: April 23, 1985

Case Name: Claim for Revocation of Corporate Tax Reassessment Disposition (昭和56年(行ツ)第36号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

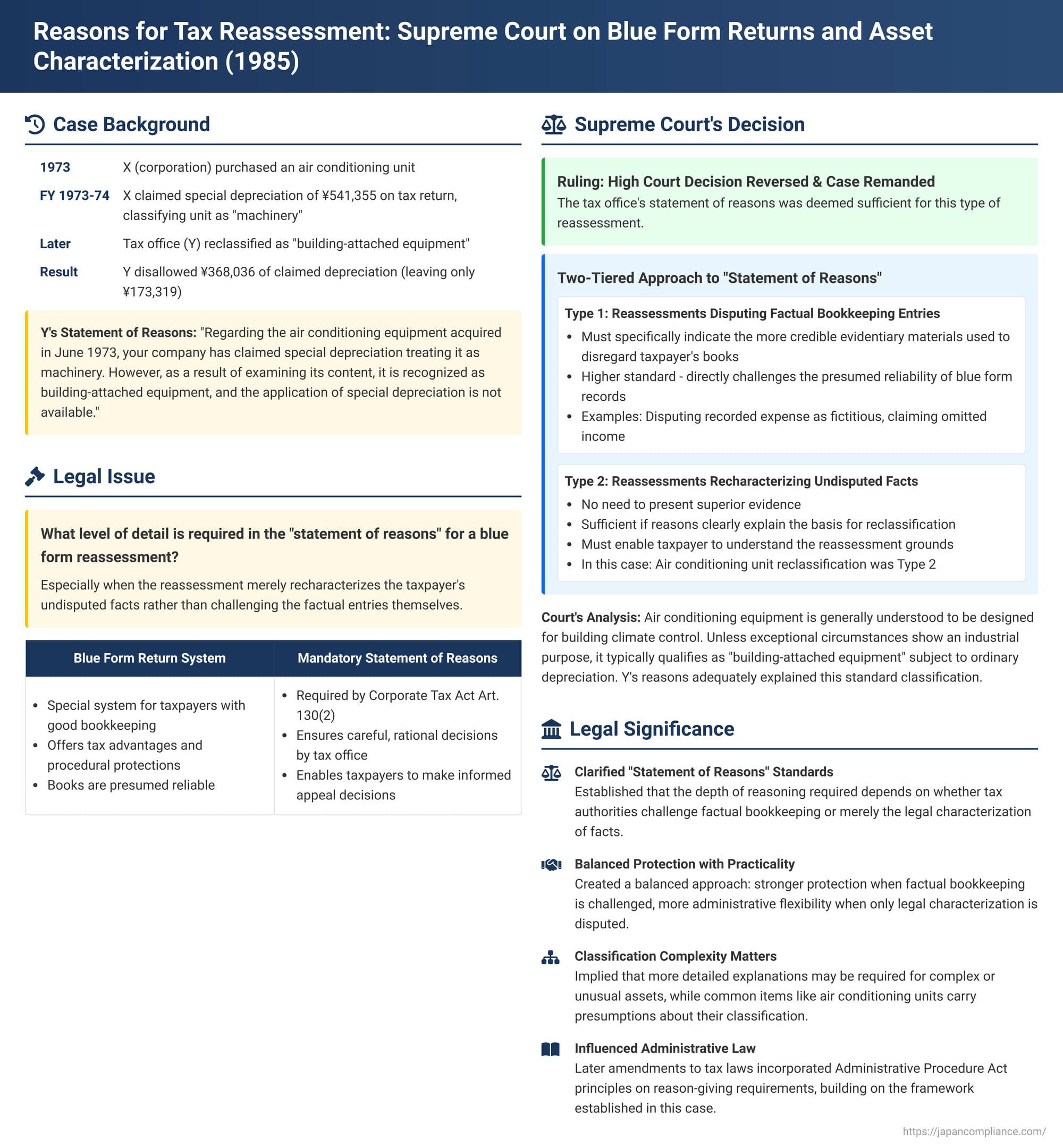

In a significant judgment on April 23, 1985, the Supreme Court of Japan clarified the required level of detail for the "statement of reasons" (理由附記 - riyū fuki) that must accompany a tax reassessment notice issued to a taxpayer filing under the "blue form return" (青色申告 - aoiro shinkoku) system. The case, involving a dispute over the depreciation of an air conditioning unit, established a distinction in the reasoning requirement based on whether the tax authority's reassessment directly challenges the taxpayer's factual bookkeeping entries or merely revises the legal or tax characterization of those undisputed facts.

The Air Conditioner Dispute: Machinery or Building Fixture?

The appellant was the head of the Nishiwaki Tax Office (Y), and the respondent was X (Komaki Teori Kabushiki Kaisha, though anonymized as X here), a corporation that had received approval to file its corporate tax returns using the blue form system. This system, available to taxpayers who maintain a certain standard of bookkeeping, offers various tax advantages but also comes with specific obligations and procedural protections.

For its fiscal year from February 1, 1973, to January 31, 1974, X filed a blue form corporate tax return. In this return, X claimed special accelerated depreciation for an air conditioning unit it had acquired in June 1973. X treated this unit as "machinery" (機械 - kikai) eligible for such special depreciation under the provisions of Article 45-2, paragraph 1 of the Special Taxation Measures Act (措置法 - Sochihō, the version before a 1974 amendment). Based on this classification, X calculated and deducted depreciation expenses amounting to ¥541,355.

The tax office head (Y) disagreed with X's treatment of the air conditioning unit. Y determined that the unit was not "machinery" eligible for special depreciation but was merely "building-attached equipment" (建物附属設備 - tatemono fuzoku setsubi) as defined under Article 2, item 24 (now item 23) of the Corporate Tax Act and Article 13, item 1 of the Corporate Tax Act Enforcement Order. As such, it was only eligible for ordinary depreciation.

Y recalculated the allowable depreciation for the air conditioning unit using the ordinary depreciation method prescribed by Article 31, paragraph 1 of the Corporate Tax Act, arriving at an amount of ¥173,319. The difference between the amount X claimed (¥541,355) and the amount Y allowed (¥173,319) was ¥368,036. Y disallowed this excess amount as a deductible expense and issued a corrective assessment (reassessment - 更正処分 kōsei shobun) to X, along with an underpayment additional tax.

The reassessment notice provided to X included the following as the reason for the correction: "1. Excess depreciation amount: ¥368,036. Regarding the air conditioning equipment acquired in June 1973, your company has claimed special depreciation treating it as machinery. However, as a result of examining its content, it is recognized as building-attached equipment, and the application of special depreciation is not available. Therefore, the excess depreciation calculated as follows is not deductible as an expense. (Type) Air conditioning equipment (Depreciation limit) ¥173,319 (Your company's calculated depreciation amount) ¥541,355 (Excess depreciation) ¥368,036."

X challenged this reassessment, arguing, among other things, that the statement of reasons provided in the notice was insufficient and therefore the reassessment was illegal. The first instance court (Kobe District Court) dismissed X's claim. However, the Osaka High Court (the appellate court) sided with X, finding the reasons inadequate. The High Court stated that the reassessment notice merely declared the air conditioning unit to be building-attached equipment without explaining why it was not considered machinery, and thus lacked a specific factual basis for the recharacterization. The tax office head (Y) then appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Standard: Adequacy of Reasons for Blue Form Reassessments

A key feature of the blue form tax return system in Japan is the enhanced procedural protection it offers to taxpayers. Article 130, paragraph 2 of the Corporate Tax Act specifically requires that when a tax office issues a reassessment to a corporation filing a blue form return, the reassessment notice must include a "statement of reasons" for the reassessment.

The Supreme Court, in this and prior cases, articulated the purpose of this requirement:

- Ensuring Careful and Rational Decision-Making: It compels the tax authority to make its decisions carefully and rationally, thereby curbing arbitrary or capricious actions.

- Facilitating Taxpayer Appeals: It informs the taxpayer of the grounds for the reassessment, enabling them to understand the tax office's position and make an informed decision about whether to file an administrative appeal or a lawsuit.

This protection is particularly important for blue form taxpayers because the system itself is premised on the reliability of their meticulously kept books and records. As such, their book entries cannot be disregarded without clear and specific justification.

The central legal question in this case was: What level of detail and specific factual grounding is required for the "statement of reasons" in a reassessment notice to a blue form taxpayer, particularly when the reassessment does not dispute the factual entries in the taxpayer's books (such as the existence of an asset or its acquisition cost) but rather changes the legal or tax characterization of those facts?

The Supreme Court's Two-Tiered Approach to "Reasons"

The Supreme Court overturned the Osaka High Court's decision and remanded the case, implying that the reasons provided by the tax office were, in principle, sufficient for the type of reassessment made in this instance, and that the High Court had erred in demanding a more detailed factual underpinning for this specific recharacterization.

The Supreme Court distinguished between two types of reassessments against blue form taxpayers and outlined the corresponding requirements for the statement of reasons:

- Type 1: Reassessments Disregarding or Denying Bookkeeping Entries: If the tax office's reassessment directly challenges or denies the factual accuracy of the taxpayer's blue form bookkeeping entries (e.g., if it claims that a recorded expense is fictitious, that income was omitted, or that the recorded acquisition cost of an asset is incorrect), then the statement of reasons in the reassessment notice must go beyond merely stating the revised account and amount. In such cases, the reasons must specifically indicate the more credible evidentiary materials (帳簿記載以上に信憑力のある資料 - chōbo kisai ijō ni shinpyōryoku no aru shiryō) upon which the tax office based its decision to disregard the taxpayer's books. This higher standard of reasoning is necessary because the blue form system grants a presumption of correctness to the taxpayer's detailed books. (The Court cited its prior landmark judgments from May 31, 1963, and April 19, 1979, which established this principle).

- Type 2: Reassessments Recharacterizing or Reinterpreting Booked Facts (Without Disputing the Facts Themselves): If, however, the tax office's reassessment does not dispute the underlying factual entries in the taxpayer's books (e.g., it accepts the recorded existence of an asset, its acquisition cost, and its acquisition date) but instead revises the taxpayer's evaluation or legal/tax characterization of those recorded facts (as in this case, where the issue was whether an acknowledged air conditioning unit was "machinery" or "building-attached equipment" for depreciation purposes), then the statement of reasons does not necessarily need to present new factual evidence superior to the taxpayer's own records.

In this scenario, the reasons provided are considered sufficient if they specifically clarify the basis for the reassessment to a degree that satisfies the fundamental purposes of the reason-stating system – namely, to curb arbitrary decisions by the tax authority and to provide the taxpayer with enough information to understand the reassessment and decide on an appeal.

Applying this framework to X's air conditioning unit:

- The Supreme Court found that the tax office's reassessment was a Type 2 reassessment. Y did not dispute the facts recorded in X's books regarding the existence of the air conditioning unit, its acquisition date, or its cost. The reassessment solely concerned the tax classification of this asset for depreciation purposes.

- Therefore, the reassessment notice did not need to cite external evidentiary materials to justify its recharacterization of the asset.

- The Court then examined the sufficiency of the reasons actually provided by Y. The notice stated that the air conditioning unit was deemed "building-attached equipment" under specific provisions of the Corporate Tax Act and its Enforcement Order, and therefore did not qualify as "machinery" eligible for special depreciation. It also included the calculation showing how the disallowed excess depreciation was derived.

- The Supreme Court found these reasons to be adequate. It reasoned that air conditioning equipment is generally understood to be designed to cool and regulate air temperature within a building. Unless exceptional circumstances demonstrate that its function is for a special industrial purpose that would qualify it as "machinery" under the Special Taxation Measures Act, it would typically be classified as "building-attached equipment" (specifically, "air conditioning equipment") or as "fixtures and furniture" (器具及び備品 - kigu oyobi bihin), both of which are subject to ordinary depreciation.

- The Court interpreted the tax office's stated reason as implying that, based on an examination of the AC unit's structure, function, and installation, it was found to be "air conditioning equipment" fitting the category of building-attached equipment.

- This level of explanation, the Supreme Court concluded, sufficiently conveyed the tax office's decision-making process without critical omissions. It allowed X to understand the legal and factual basis for the reassessment (i.e., the reclassification of the asset) and provided enough information for X to make an informed decision about appealing the substance of that reclassification. Thus, the reasons fulfilled the objectives of curbing administrative arbitrariness and facilitating taxpayer appeals, and therefore met the requirements of Article 130, paragraph 2 of the Corporate Tax Act.

The High Court had erred in law by demanding a more detailed factual justification for this type of recharacterization. The Supreme Court therefore quashed the High Court's judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings on the substantive issue of whether the air conditioning unit actually qualified as "machinery" or was indeed "building-attached equipment."

Analysis and Implications

The Supreme Court's 1985 decision in this case provides critical guidance on the procedural requirements for tax reassessments involving blue form taxpayers:

- Clarification of "Statement of Reasons" Standards: The ruling established an important distinction regarding the necessary level of detail in reassessment notices. The stringency of the reason-giving requirement depends on whether the tax authority is challenging the taxpayer's factual bookkeeping or merely their legal interpretation or tax characterization of undisputed facts.

- Balancing Taxpayer Protections with Administrative Practicality: The decision strikes a balance. For blue form filers, whose books are presumed reliable, a direct challenge to the factual accuracy of those books requires a high standard of justification from the tax office, including the presentation of superior evidence. However, for disputes over legal characterization or interpretation of agreed facts, while reasons must still be clear and specific enough to prevent arbitrariness and allow for an informed appeal, the requirement to present overriding factual evidence is lessened. This acknowledges the practicalities of tax administration.

- Presumptions for Common Classifications: The Supreme Court's willingness to infer a common understanding for relatively standard items like air conditioning units (i.e., they are generally building-attached equipment unless proven otherwise) suggests that for less common or more complex assets or transactions, a more detailed explanation might be necessary even in a recharacterization-type reassessment to meet the sufficiency standard.

- Impact of Later Integration of Administrative Procedure Act Principles: Legal commentary notes that subsequent to this judgment, Japan's General Act of National Taxes was amended (effective from 2013, based on a 2011 law change) to explicitly incorporate the principles of the Administrative Procedure Act concerning the requirement to provide reasons for administrative dispositions (see General Act of National Taxes Article 74-14). This legislative change might influence the ongoing evolution of judicial standards regarding what constitutes an adequate statement of reasons in tax assessments, potentially aligning them more closely with general administrative law principles.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1985 decision remains a key precedent regarding the "statement of reasons" requirement for tax reassessments issued to blue form taxpayers in Japan. It clarified that when a reassessment does not dispute the taxpayer's underlying factual records but rather revises the tax characterization or legal interpretation of those facts, the reasons provided in the reassessment notice must clearly and specifically articulate the basis for this recharacterization. This must be done to a degree that allows the taxpayer to understand the decision and to prevent arbitrary action by the tax authorities, but it does not necessarily require the tax office to present new factual evidence that contradicts the taxpayer's own books. This ruling provides an important balance between upholding the procedural rights associated with the blue form tax return system and the practical needs of tax administration.