Substance Over Form: Japan's Supreme Court Bars Estranged Spouses from Survivor Benefits

Japan’s Supreme Court held that estranged spouses in a de facto divorce cannot claim survivor benefits under SERAMA or corporate pension funds, prioritising real dependency over formality.

TL;DR

- Japan’s Supreme Court (Mar 25 2021) ruled that a legally married but long‑separated spouse is not an eligible “spouse” for survivor benefits.

- The decision applies beyond public‐sector pensions to SERAMA and defined‑benefit corporate pension funds.

- Eligibility now turns on the actual, ongoing marital relationship, not mere registry status.

- Children or other dependants move up in priority when an estranged spouse is disqualified.

- The ruling signals broader application of the 1983 “de facto divorce” doctrine across Japanese social‑security schemes.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: A Broken Marriage and Competing Claims

- Lower Court Rulings: De Facto Divorce Disqualifies Legal Spouse

- Legal Issue: Does the “De Facto Divorce” Rule Apply Broadly?

- The Supreme Court's Analysis (March 25 2021)

- Implications and Significance

- Conclusion

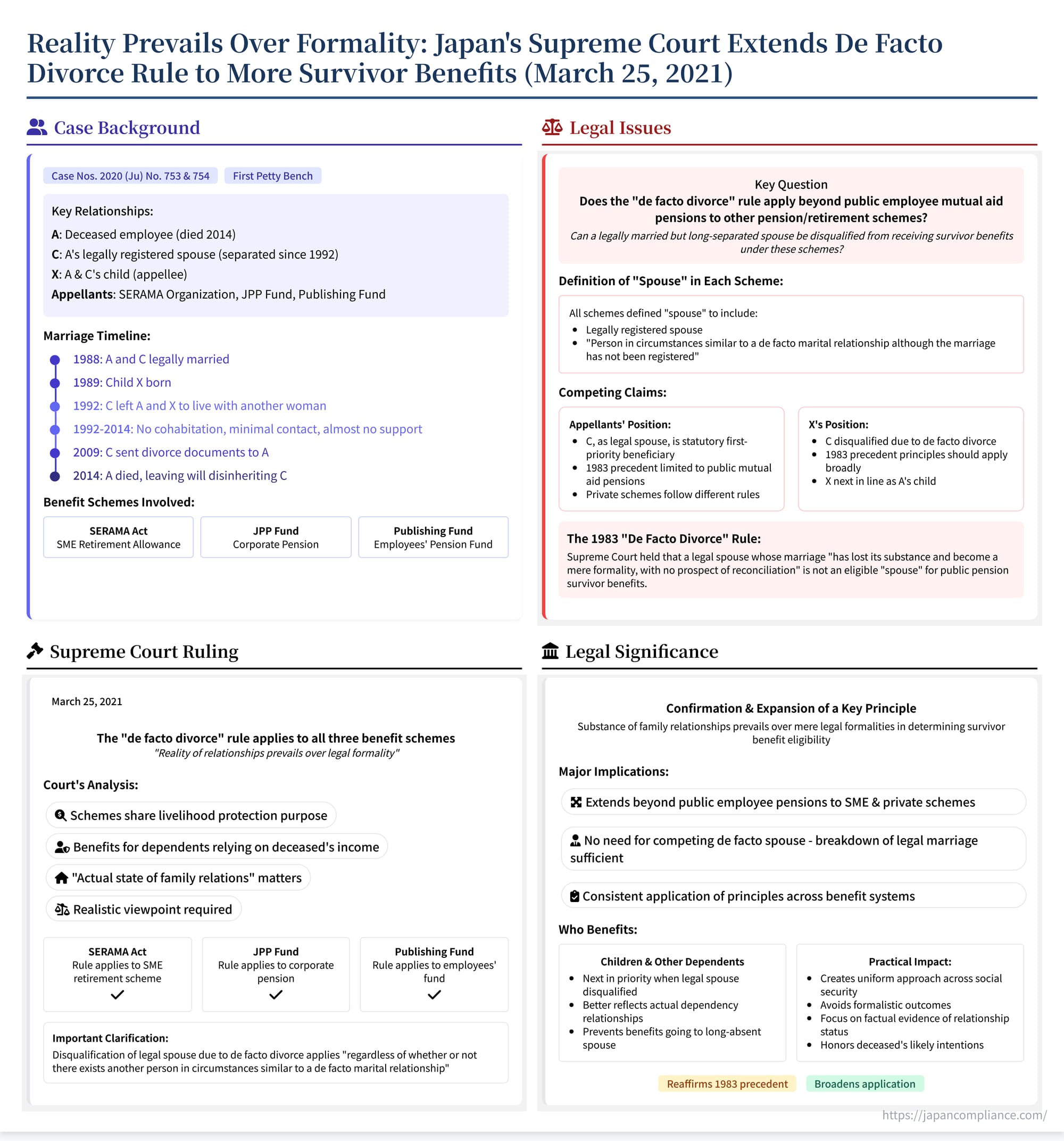

On March 25, 2021, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a judgment further solidifying and extending a crucial principle in Japanese social security law: a legally married spouse may be disqualified from receiving survivor benefits if the marriage existed in name only and was effectively a "de facto divorce" at the time of the insured person's death (Case Nos. 2020 (Ju) No. 753 & 754, "Retirement Allowance, etc. Claim Case"). This decision applied the principle, previously established for public employee mutual aid pensions, to survivor benefits under the Smaller Enterprise Retirement Allowance Mutual Aid Act (SERAMA Act) and specific corporate/employees' pension fund schemes. The ruling underscores the consistent emphasis within Japan's social benefit systems on the substantive reality of family relationships rather than strict legal formalities when determining eligibility for survivor support.

Factual Background: A Broken Marriage and Competing Claims

The case involved a dispute over survivor benefits following the death of A, focusing on the status of her long-estranged legal husband:

- The Deceased and Her Dependents: A passed away in Heisei 26 (2014). At the time of her death, she was employed by Company B. A had one child, the appellee X.

- Pension/Retirement Schemes: Due to her employment, A was covered by several retirement and pension schemes:

- SERAMA: Company B had a retirement allowance mutual aid contract for A with the appellant Organization (likely the Organization for Small & Medium Enterprises and Regional Innovation, JAPAN) under the SERAMA Act (Chūshō Kigyō Taishokukin Kyōsai Hō). This scheme provides retirement benefits, including death benefits payable to survivors.

- JPP Fund: A was a member of the appellant JPP Fund, a corporate pension fund established under the Defined Benefit Corporate Pension Act (DBCP Act - Kakutei Kyūfu Kigyō Nenkin Hō). Its bylaws provided for survivor benefits.

- Publishing Fund: A was a member of the Publishing Employees' Pension Fund, established under the pre-2013 Employees' Pension Insurance Act (EPI Act - Kōsei Nenkin Hoken Hō). This fund, whose rights and obligations were succeeded by the appellant Publishing Fund, also provided for survivor benefits (in this case, a lump-sum).

- Survivor Benefit Provisions: All three schemes (SERAMA Act, JPP Fund bylaws, Publishing Fund bylaws) designated the "spouse" (配偶者 - haigūsha) as the highest-priority recipient of survivor benefits. Critically, like many Japanese social security laws, the definition of "spouse" explicitly included not only the legally registered spouse but also a person "in circumstances similar to a de facto marital relationship although the marriage has not been registered." The deceased's child was typically the next-in-line beneficiary after the spouse.

- The Estranged Husband (C): A had legally married C in Showa 63 (1988), and they had one child, X (appellee), in Heisei 1 (1989). However, C left A and X around Heisei 4 (1992) to live with another woman. From that point until A's death over 20 years later:

- C never lived with A and X again.

- C met with A only a few times.

- C provided almost no financial support for marital expenses.

- Around Heisei 21 (2009), C sent A documents requesting a divorce by mutual agreement.

- A had the intention to divorce but delayed proceedings out of concern for the potential impact on X, who was then a university student seeking employment.

- By the time X graduated in Heisei 26 (2014), A's health had deteriorated significantly due to illness, preventing her from completing divorce procedures before her death later that year.

- C was notified of A's death but did not attend the funeral.

- The day before her death, A executed an emergency will explicitly disinheriting C (as a presumptive legal heir) and leaving her entire estate to X.

- Subsequently, the Tokyo Family Court issued a ruling formally disinheriting C as an heir based on the long-term separation and lack of support.

- The Lawsuit: After A's death, X applied to the three appellant entities (the Organization, JPP Fund, Publishing Fund) for the respective survivor benefits (retirement allowance, survivor benefit, survivor lump-sum). The claims were presumably rejected because C remained A's legally registered spouse. X then filed suit, arguing that the marriage between A and C was in a state of de facto divorce at the time of A's death. Therefore, C did not qualify as the eligible "spouse" under the relevant laws and bylaws, making X, as the child and next-in-line survivor, the rightful recipient.

Lower Court Rulings: De Facto Divorce Disqualifies Legal Spouse

The first instance court initially ruled against X, likely focusing on C's formal legal status as the spouse. However, the High Court reversed this decision. It found that the factual circumstances clearly demonstrated that the marriage between A and C had irretrievably broken down long before A's death, lost all substance, and become a mere formality, with no prospect of reconciliation. Applying the principles established by the Supreme Court in a Showa 58 (1983) decision concerning public employee mutual aid pensions (analyzed in a previous post), the High Court concluded that C, despite being the legal spouse, did not qualify as the "spouse" for the purpose of receiving these survivor benefits due to the de facto divorce. Consequently, it ruled that X was entitled to the benefits as the next eligible survivor. The three appellant entities appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

Legal Issue: Does the "De Facto Divorce" Rule Apply Broadly?

The core legal question before the Supreme Court was whether the principle established in its 1983 ruling – that a legally married spouse in a state of de facto divorce can be disqualified from receiving survivor benefits – applied beyond the specific context of public employee mutual aid pensions to other statutory and private pension/retirement schemes like those governed by the SERAMA Act, the DBCP Act, and the old EPI Act (via fund bylaws), especially when these schemes use similar definitions for eligible survivors including de facto spouses.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (March 25, 2021)

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated March 25, 2021, dismissed the appeals from all three appellant entities, thereby affirming the High Court's decision in favor of X. The Court systematically applied the "de facto divorce" principle established in the 1983 precedent to each of the benefit schemes in question.

1. Application to SERAMA Act Retirement Allowance:

- Purpose & Survivor Definition: The Court noted the SERAMA Act's purpose (promoting SME employee welfare) and its specific definition of eligible survivors for death benefits (Art. 14), which prioritizes the spouse (including de facto spouse) and ranks other relatives based partly on financial dependency. This structure, the Court reasoned, indicates that the primary objective is "livelihood protection for dependents who relied on the insured person's income" (hikyōsaisha no shūnyū ni ikyo shite ita izoku no seikatsu hoshō o omona mokuteki to shite), similar to the social security purpose of public pensions.

- Need for Realistic Interpretation: Given this purpose, the Court stated that the scope of eligible survivors should be understood based on the "actual state of family relations" (kazoku kankei no jittai) and from a "realistic viewpoint" (genjitsuteki na kanten), consistent with how eligibility is determined for public benefits with a social security character.

- Applying the 1983 Precedent: Therefore, the Court explicitly invoked and applied the reasoning from its Showa 58 (1983) judgment: the term "spouse" under SERAMA Art. 14(1)(i) should be interpreted to mean someone who was "mutually cooperating and actually maintaining a shared life constituting a marital relationship in accordance with social norms."

- Disqualification Rule: Consequently, a legally registered spouse whose marriage "has lost its substance and become a mere formality, and that state has become fixed with no prospect of dissolution [reconciliation] in the near future, i.e., is in a state of de facto divorce," does not qualify as a "spouse" under SERAMA Art. 14(1)(i).

- Irrelevance of Competing De Facto Spouse: The Court explicitly added that this disqualification applies based on the state of the legal marriage itself, "regardless of whether or not there exists another person in circumstances similar to a de facto marital relationship" besides the legal spouse. (This clarified a point sometimes debated after the 1983 ruling).

2. Application to Corporate/Employees' Pension Funds (JPP Fund / Publishing Fund):

- Similar Purpose and Structure: The Court examined the relevant provisions of the DBCP Act (Art. 48) and the old EPI Act/Pension Fund Ordinance (Art. 26) authorizing survivor benefits, as well as the specific bylaws of the JPP Fund and Publishing Fund. It noted their stated purposes (contributing to stability and welfare, supplementing public pensions) and their similar structures for defining eligible survivors (prioritizing spouses including de facto spouses, ranking other relatives).

- Livelihood Protection Goal: Based on this structure, the Court concluded that these private/occupational pension fund survivor benefits also primarily aim at "livelihood protection for dependents who relied on the benefit target person's income" (kyūfu taishōsha no shūnyū ni ikyo shite ita izoku no seikatsu hoshō o omona mokuteki to shite).

- Same Interpretation Applies: Given the shared purpose and similar structure for defining eligible survivors, the Court held that the interpretation applied to the SERAMA Act (and derived from the 1983 public pension case) should apply here as well. A legally married spouse in a state of de facto divorce does not qualify as the eligible "spouse" under these fund rules either.

3. Application to the Facts:

The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's factual finding that the marriage between A and C was, at the time of A's death, indeed in a state of de facto divorce – it had lost its substance, become a mere formality, and was permanently broken with no prospect of reconciliation.

Conclusion on Eligibility: Therefore, C did not qualify as the eligible "spouse" for any of the three benefits (SERAMA retirement allowance, JPP survivor benefit, Publishing Fund survivor lump-sum). Since C, the first-priority potential recipient, was disqualified, X, as the child and next-in-line eligible survivor under the respective rules, was entitled to receive the benefits.

Implications and Significance

This 2021 Supreme Court decision significantly clarifies and broadens the application of the "de facto divorce" doctrine in Japanese law concerning survivor benefits:

- Confirmation and Extension of the 1983 Doctrine: It firmly reaffirms the principle established in the 1983 Supreme Court case: for survivor benefit eligibility in social security contexts, the substance of a marital relationship matters more than mere legal form. Crucially, it extends this principle beyond public employee mutual aid systems to the widely applicable SERAMA retirement scheme and to corporate/employees' pension funds governed by similar statutory frameworks and bylaws.

- Prioritizing Substantive Family Ties: The ruling consistently emphasizes that where survivor benefits are intended for livelihood protection based on dependency, eligibility should reflect the actual functioning family unit. A legal marriage that has completely broken down does not represent such a unit.

- Clarification on "Competing" De Facto Spouses: The decision explicitly clarifies that the disqualification of a legally married spouse due to de facto divorce does not depend on the existence of another person living in a de facto marital relationship with the deceased. The breakdown of the legal marriage itself is the key factor.

- Broad Applicability: The reasoning, tying the interpretation to the common purpose of livelihood support and similar statutory/regulatory structures defining survivors, suggests this principle likely applies to a wide range of public and private survivor benefit schemes in Japan that include de facto spouses in their definition of eligible beneficiaries.

- Importance of Factual Evidence: The ruling underscores the critical importance of detailed factual evidence in establishing a state of "de facto divorce." Courts will examine the duration of separation, reasons for separation, lack of interaction or support, absence of reconciliation efforts, formation of new stable relationships, and expressed intentions (like divorce requests or disinheritance) to determine if the legal marriage has become merely a "hollow shell."

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 25, 2021, judgment provides clear guidance on the status of legally married but de facto divorced spouses concerning survivor benefits across various Japanese retirement and pension schemes. By extending the principle established in its 1983 ruling, the Court confirmed that eligibility hinges on the substantive reality of the marital relationship, not merely the legal registration. A spouse whose marriage has lost all substance, become permanently broken, and exists only as a legal formality is generally not entitled to survivor benefits designed to support the deceased's actual dependents. This decision reinforces the focus on functional family relationships and the purpose of livelihood protection within Japan's social benefit landscape.

- When a Lie Becomes a Crime: Japan's Landmark Case on Lying for an Arrested Friend

- The Scapegoat Gambit: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Aiding an Arrested Criminal's Escape

- Memory vs. Truth: How Japan's High Court Defined Perjury Over a Century Ago

- Overview of the Japanese Pension System – Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

- Small and Medium‑Sized Enterprise Retirement Allowance Mutual Aid System (English PDF)

- Public Pensions for Survivors and the Disabled – MHLW White Paper Section