Reading the Fine Print: Japan's Supreme Court on Literal Interpretation in Tax Law – The Hostess Remuneration Case

Judgment Date: March 2, 2010

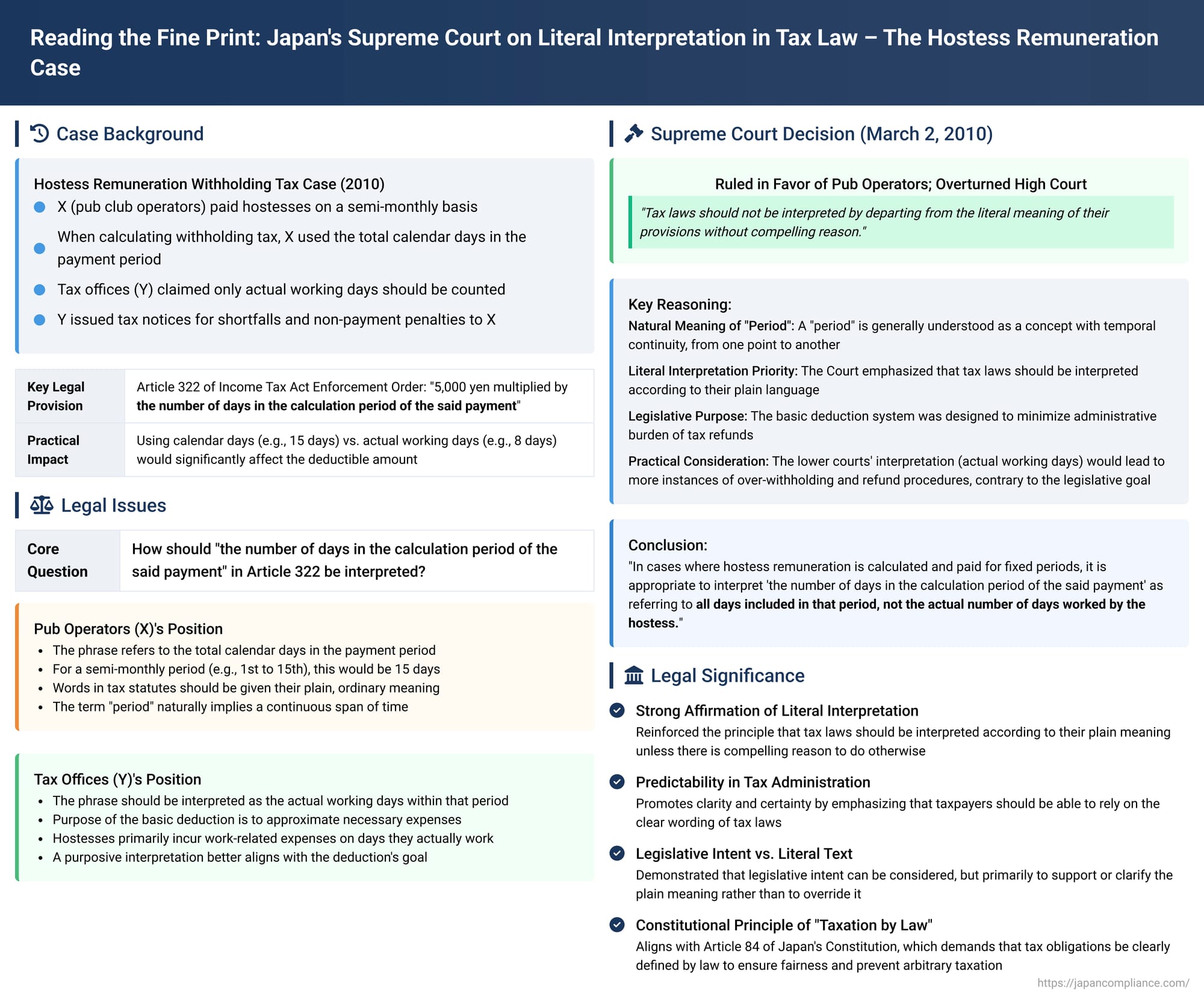

In a significant ruling that emphasized the importance of adhering to the literal text of tax laws, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan addressed a dispute over the calculation of withholding tax on remuneration paid to hostesses. The case turned on the precise meaning of "the number of days in the calculation period of the said payment" – a phrase crucial for determining a daily deductible amount. The Court's decision to favor a literal interpretation over a more purposive one adopted by lower courts has important implications for how tax statutes and regulations are to be understood and applied in Japan.

Background: Withholding Tax on Hostess Remuneration

The appellants, X, were operators of pub clubs in Tokyo. The dispute concerned the method they used to calculate and remit withholding income tax on remuneration paid to hostesses working at their establishments.

Under Japanese tax law (specifically, Article 204, Paragraph 1, Item 6 of the Income Tax Act), payers of remuneration for services rendered by hostesses and similar entertainers are obligated to withhold income tax at source. The amount of tax to be withheld is determined according to Article 205, Item 2 of the Income Tax Act and Article 322 of the Income Tax Act Enforcement Order. This calculation involves taking "the amount paid on one occasion to the same person," deducting a specified sum, and then applying a 10% tax rate to the remainder.

The critical deductible sum is defined in Article 322 of the Enforcement Order as "5,000 yen multiplied by the number of days in the calculation period of the said payment" (当該支払金額の計算期間の日数 - tōgai shiharaikingaku no keisankikan no nissū). This method is referred to as the "basic deduction method" (基礎控除方式 - kiso kōjo hōshiki).

X, the pub club operators, paid their hostesses on a semi-monthly basis. When calculating the withholding tax, X interpreted "the number of days in the calculation period of the said payment" as the total number of calendar days within each semi-monthly payment period (e.g., if a period was from the 1st to the 15th of the month, they used 15 days).

However, the heads of the relevant tax offices, Y (appellees), took a different view. They asserted that the phrase should refer only to the actual number of days each hostess worked during that semi-monthly period. Based on this interpretation, the tax offices determined that X had under-withheld and underpaid income tax. Consequently, they issued notices of tax due for the shortfalls and also imposed non-payment penalties (不納付加算税 - funōfu kasanzei).

X challenged these assessments, leading to the legal battle.

The Lower Courts' Rulings: A Purposive Approach

Both the Tokyo District Court (first instance) and the Tokyo High Court (appellate court) ruled in favor of the tax authorities, Y. Their reasoning centered on a purposive interpretation of the law:

- Approximating Necessary Expenses: The lower courts reasoned that the purpose of the basic deduction method in the context of hostess remuneration—who are typically classified as individual business operators—was to allow a deduction that approximates the actual necessary expenses they incur in earning their income.

- Expenses on Working Days: They further reasoned that hostesses would primarily incur such work-related expenses on the days they actually worked. Therefore, linking the 5,000 yen daily deduction to the number of actual working days would result in a deductible amount that more closely mirrors the likely actual expenses than using the total calendar days in the payment period (which would include non-working days).

- Statutory Interpretation Principles: The Tokyo High Court, addressing X's argument that tax laws should be interpreted literally, acknowledged the principle of literal interpretation. However, it also stated that because it is legislatively impossible for the wording of laws to flawlessly cover every conceivable social phenomenon, the purpose and objective of the statute must be fully considered during interpretation. This, the High Court asserted, is a fundamental principle of statutory interpretation applicable to all laws, including tax laws.

Thus, the lower courts concluded that "the number of days in the calculation period of the said payment" meant the actual number of days worked by the hostesses within each semi-monthly payment computation period.

X appealed this interpretation to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Prioritizing Literal Meaning

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case, finding that the lower courts had erred in their interpretation of the critical phrase in Article 322 of the Income Tax Act Enforcement Order.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

1. The Natural Meaning of "Period" (期間 - kikan)

The Court began with a linguistic analysis of the term "period":

"Generally, a 'period' is understood as a concept possessing temporal continuity, such as the span of time from one point to another. Therefore, it is natural to interpret 'the calculation period of the said payment' in Article 322 of the Enforcement Order as also being a concept with temporal continuity, from the first day to the last day of the period for which the said payment was calculated. No provision can be found that would serve as a basis for adopting a different interpretation."

In essence, the Court found that the plain, ordinary meaning of "period" implies a continuous block of time, not a collection of discrete working days.

2. Critique of the Lower Courts' Purposive Interpretation

The Supreme Court directly addressed and critiqued the purposive approach taken by the lower courts:

"The lower court ruled as described above [that 'days' should mean actual working days to approximate expenses], but tax laws should not be interpreted by departing from the literal meaning of their provisions without compelling reason (租税法規はみだりに規定の文言を離れて解釈すべきものではなく - Sozei hōki wa midari ni kitei no mongon o hanarete kaishaku subeki mono dewa naku)."

This statement is a cornerstone of the judgment, signaling a strong preference for literalism in tax law interpretation.

The Court found the lower courts' interpretation problematic for two main reasons:

- Linguistic Difficulty: Adopting the "actual working days" interpretation was, as the Court had already established, "difficult from a literal wording perspective."

- Misalignment with Legislative Purpose: The Supreme Court then considered the legislative intent behind the basic deduction method for hostess remuneration. It noted that explanations from those involved in drafting the legislation indicated that the purpose of this system was "to minimize, as much as possible, the administrative burden associated with tax refunds related to source-withheld income tax."

The lower courts' interpretation (using actual working days) would generally lead to smaller daily deductions, potentially resulting in more instances of over-withholding and thus a greater need for subsequent refund procedures. This outcome, the Supreme Court found, was contrary to the stated legislative goal of simplifying the process and reducing refunds. Therefore, from this perspective as well, the lower courts' interpretation was "difficult to adopt."

3. The Correct Interpretation

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded:

"Thus, in cases where hostess remuneration is calculated and paid for fixed periods, it is appropriate to interpret 'the number of days in the calculation period of the said payment' in Article 322 of the Enforcement Order as referring to all days included in that period, not the actual number of days worked by the hostess."

4. Application to the Facts of the Case

The Court noted that X, the pub club operators, calculated and paid remuneration to each hostess for each semi-monthly "compilation period" (shūkei kikan). Therefore, applying its interpretation, the Court held:

"In the present case, the aforementioned 'number of days in the calculation period of the said payment' should be the total number of calendar days in each of the subject compilation periods."

Judgment and Remand

The Supreme Court found that the High Court's judgment, being based on a different interpretation, contained a violation of law that clearly affected the outcome. The appeal by X was therefore found to have merit. The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case back to the Tokyo High Court. The purpose of the remand was for the High Court to recalculate the correct amount of withholding income tax and any applicable non-payment penalties, using the Supreme Court's interpretation: that the deductible amount should be 5,000 yen multiplied by the total number of calendar days in each semi-monthly payment period.

Significance and Implications of the Ruling

This decision by Japan's Supreme Court is highly significant in the field of tax law interpretation:

- Emphasis on Literal Interpretation: The case is most notable for its strong affirmation of the principle of literal interpretation (bunri kaishaku) for tax statutes and regulations. The Court's direct statement that "tax laws should not be interpreted by departing from the literal meaning of their provisions without compelling reason" serves as a clear guideline for courts, tax authorities, and taxpayers. It suggests that where the language of a tax provision is clear, that meaning should generally prevail, even if a purposive interpretation might seem to lead to a more "equitable" or "economically sensible" outcome in the eyes of some.

- Role of Legislative Intent: While prioritizing literal meaning, the Court did not entirely dismiss legislative intent. However, it used legislative intent (the aim to reduce refund procedures) to bolster its literal interpretation and to critique the lower courts' purposive approach, which it found ran contrary to this intent. This indicates that legislative history and stated purposes can be relevant, but perhaps more so when they align with or clarify the plain meaning of the text, rather than contradicting it.

- Clarity for Taxpayers and Administrators: The ruling provides concrete guidance on a specific, practical aspect of withholding tax calculation for a particular industry. More broadly, it reinforces the idea that taxpayers should be able to rely on the clear wording of tax laws, and that tax administration should be carried out based on such clear meanings to ensure predictability and fairness. This aligns with the overarching principle of "taxation by law" enshrined in Article 84 of the Japanese Constitution, which demands that tax obligations be clearly defined by law.

- Ongoing Debate on Interpretive Methods: While this case champions literalism, it exists within a broader landscape of Japanese Supreme Court jurisprudence where, on occasion (particularly in cases where a literal interpretation might lead to results perceived as highly inequitable or absurd), more purposive or systemic interpretations have been adopted. This ruling thus contributes to the ongoing discussion about the appropriate balance between textual fidelity and broader interpretative considerations in tax law.

The "Hostess Remuneration Case" serves as a strong reminder that in the complex world of taxation, the words of the law matter immensely, and departures from their plain meaning require very strong justification.