Race to the Proceeds: Preferential Rights vs. General Creditors in Japanese Supreme Court Case

Date of Judgment: July 19, 1985

Case Name: Action for Objection to Distribution Table

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

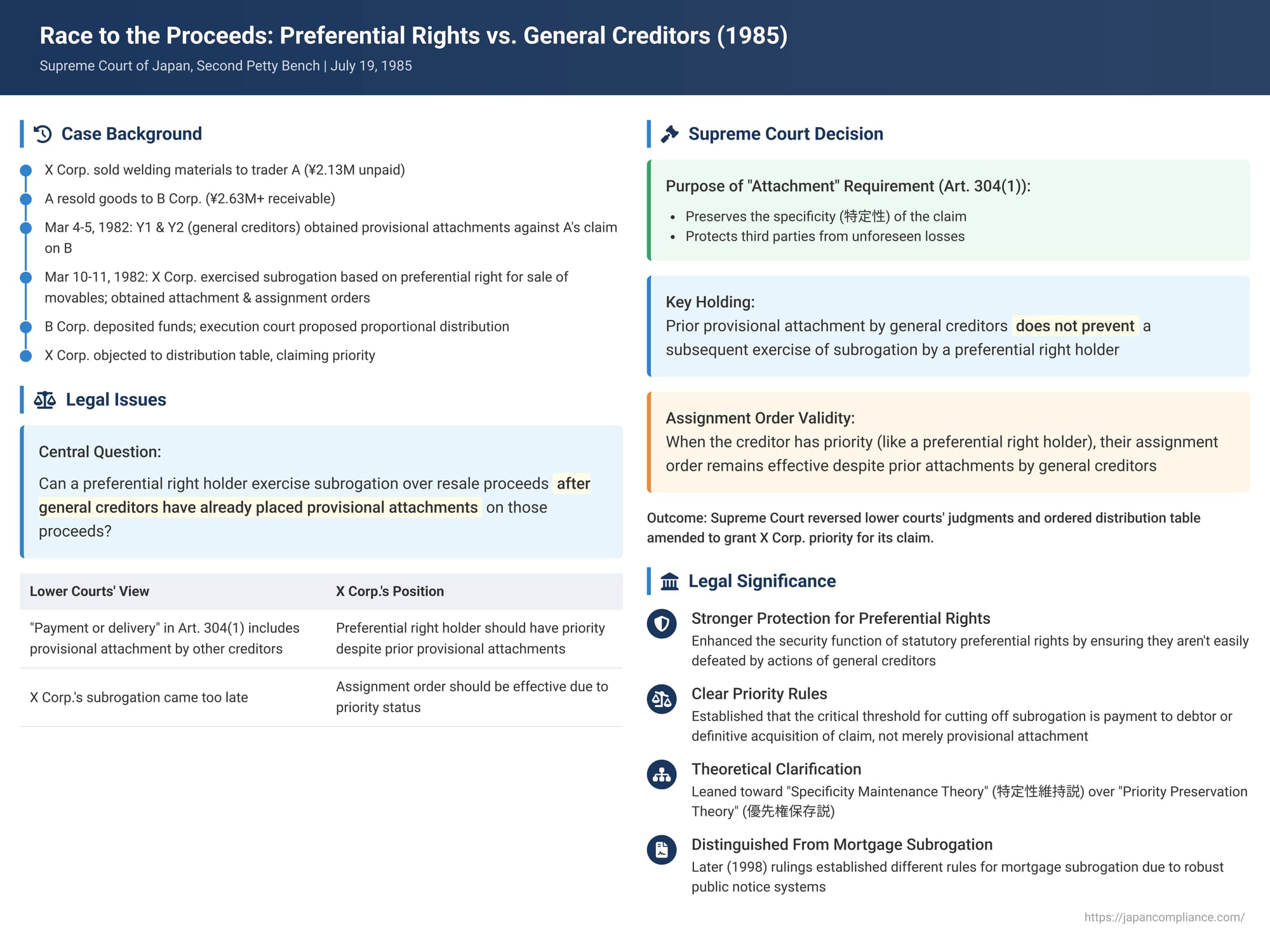

In the world of commerce, creditors employ various means to secure repayment of debts. Beyond consensual security like mortgages or pledges, Japanese law provides for "statutory preferential rights" (sakidori tokken). These rights arise automatically by law for certain types of claims and can offer a creditor priority over specific assets of their debtor. A crucial feature of these preferential rights is the ability to pursue the proceeds or substitutes for the property over which the right exists, a concept known as "subrogation over property" (butsujō daii). However, the path to exercising this right can become complex when other creditors are also vying for the debtor's assets. A significant Supreme Court judgment on July 19, 1985, addressed a critical scenario: Can a creditor holding a statutory preferential right for the sale of movables successfully exercise subrogation over the resale proceeds of those goods if other general creditors of the debtor have already provisionally attached those same proceeds?

The Commercial Dispute: A Supplier, a Debtor, and Competing Creditors

The case unfolded from a series of commercial transactions and subsequent creditor actions:

- X Corp. had sold welding materials and other movable goods to an individual trader, A. A still owed X Corp. an outstanding accounts receivable balance of over ¥2.13 million.

- A, without having paid X Corp., then resold these goods to B Corp. for a sum exceeding ¥2.63 million. This created a claim for resale proceeds (the "Resale Proceeds Claim") in favor of A against B Corp.

- Before X Corp. took action, two general creditors of A, namely Y1 Corp. and Y2 Financial, moved to secure their own claims. On March 4, 1982, both Y1 Corp. and Y2 Financial obtained separate provisional attachment orders (kari sashiosae meirei) from the court against A's Resale Proceeds Claim. These orders were served on the third-party obligor, B Corp., on March 4 and March 5, 1982, respectively.

- Subsequently, on March 10, 1982, X Corp. took steps to enforce its statutory preferential right for the sale of movables concerning its unpaid claim against A. Asserting its right of subrogation over A's Resale Proceeds Claim, X Corp. obtained a court order attaching ¥2.13 million of this claim and also secured an assignment order (tempu meirei) for this amount in its favor. These orders were served on B Corp. on March 11, 1982.

- Faced with these competing claims and attachments, B Corp. deposited the disputed Resale Proceeds Claim amount with a legal deposit office (kyōtaku).

- The execution court, tasked with distributing these deposited funds, prepared a distribution table (haitōhyō). This table proposed to allocate the funds proportionally among X Corp., Y1 Corp., and Y2 Financial, according to the amounts of their respective claims. The court's rationale was that X Corp.'s assignment order was rendered ineffective by the prior provisional attachments obtained by Y1 Corp. and Y2 Financial (citing Article 159, Paragraph 3 of the Civil Execution Act, which generally invalidates an assignment order if other attachments are already in place). Essentially, the court found that no creditor had priority.

- X Corp. disagreed strongly with this proposed distribution. It filed a formal lawsuit objecting to the distribution table (haitō igi no uttae), arguing that its exercise of subrogation based on a statutory preferential right was not defeated by prior provisional attachments from general creditors. X Corp. contended that its assignment order was therefore valid and that it was entitled to priority in the distribution of the funds.

The Lower Courts' View: Prior Attachment Blocks Subrogation

The District Court and the High Court both ruled against X Corp. Their reasoning centered on the interpretation of Article 304, Paragraph 1, proviso of the Civil Code. This proviso requires a preferential right holder wishing to exercise subrogation to "attach" the target claim (e.g., resale proceeds) "before its payment or delivery" to the debtor.

The lower courts interpreted this "attachment" by the preferential right holder as a necessary step to perfect the right of subrogation and make it effective against third parties, akin to a form of public notice. They reasoned that there was no justification for allowing a preferential right, which itself often lacks strong public notice, to prevail over third parties (like Y1 Corp. and Y2 Financial) who had already taken the formal step of provisionally attaching the claim. Consequently, they held that the phrase "payment or delivery" in the proviso should be construed broadly to include situations where general creditors have already executed a provisional attachment on the target claim. Thus, X Corp.'s attempt to exercise subrogation came too late, after Y1 Corp. and Y2 Financial had already established their provisional attachments.

The Supreme Court's Judgment (July 19, 1985): A Different Perspective

The Supreme Court reversed the decisions of the lower courts and ruled in favor of X Corp., providing a significant clarification on the operation of subrogation for statutory preferential rights.

- Purpose of the "Attachment" Requirement in Article 304(1) Proviso: The Supreme Court began by explaining the legislative intent behind requiring the preferential right holder to attach the target claim before its payment or delivery. This requirement serves two main purposes:

- Preserving Specificity: The attachment by the preferential right holder legally prohibits the third-party obligor (B Corp., in this case) from paying the money to the debtor (A). It also prohibits the debtor (A) from collecting the claim from the third-party obligor or from assigning it to someone else. This freezes the target claim, maintaining its "specificity" (tokuteisei) and thereby securing the effectiveness of the right of subrogation.

- Protecting Third Parties: It aims to prevent unforeseen losses that might be suffered by the third-party obligor (who might otherwise innocently pay the debtor) or by other third parties who might subsequently acquire the claim or obtain an assignment order over it.

- Prior Provisional Attachment by General Creditors is No Bar: Crucially, the Supreme Court held that if a general creditor has merely executed a provisional attachment or a final attachment against the target claim, this action does not prevent a holder of a statutory preferential right from subsequently exercising their right of subrogation against that same claim. The Court cited its own earlier ruling (Supreme Court, February 2, 1984, Minshū Vol. 38, No. 3, p. 431) which had laid down this general principle.

- X Corp.'s Subrogation was Valid: Applying this principle to the facts, Y1 Corp. and Y2 Financial were general creditors who had merely executed provisional attachments against A's Resale Proceeds Claim. This did not bar X Corp. from subsequently exercising its right of subrogation based on its statutory preferential right for the sale of movables. The lower courts had therefore erred in their interpretation and application of Article 304, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code.

- X Corp.'s Assignment Order was Effective: The Supreme Court then addressed the validity of X Corp.'s assignment order. Article 159, Paragraph 3 of the Civil Execution Act generally renders an assignment order ineffective if, by the time it is served on the third-party obligor, other creditors have already attached the claim, provisionally attached it, or made a demand for distribution. However, the Supreme Court clarified that this rule has an exception: if the creditor who obtained the assignment order is a creditor with priority – such as a preferential right holder exercising subrogation – then the assignment order is effective, notwithstanding prior attachments by general creditors. Since X Corp. was exercising a preferential right, its assignment order was valid and effective despite the earlier provisional attachments by Y1 Corp. and Y2 Financial.

- Validity of B Corp.'s Deposit and X Corp.'s Objection to Distribution: The Court also considered the procedural aspects of B Corp.'s deposit and X Corp.'s objection. It noted that even if, legally, there wasn't a true "competing attachment" situation (because X Corp.'s assignment order had priority and effectively transferred the claim to X Corp.), a deposit made by a third-party obligor under Civil Execution Act Article 156, Paragraph 2 (or its analogous application) can be considered valid if the third-party obligor cannot be expected to make an accurate determination on the complex legal question of the assignment order's validity and priority. In such a case, if the execution court then prepares a distribution table that incorrectly assumes the assignment order is ineffective and allocates funds proportionally among all attaching creditors, the creditor who rightfully holds the effective assignment order can legally file an objection to the distribution and sue to have the table amended to reflect their priority. X Corp.'s actions were therefore deemed proper.

- Outcome: The Supreme Court concluded that X Corp.'s claims were entirely justified. It quashed the lower courts' judgments and ordered the distribution table to be amended to grant priority to X Corp. for its claim of ¥2.13 million.

Key Legal Principles at Play

This judgment illuminates several important legal concepts:

- Sakidori Tokken (Statutory Preferential Right for Sale of Movables): This right (Civil Code Articles 311(v), 321) provides sellers of movable goods with a priority claim over those goods for the unpaid purchase price. It's a non-consensual security interest that arises by operation of law.

- Butsujō Daii (Subrogation over Property): As outlined in Civil Code Article 304, this allows the holder of a preferential right (and other specified security interests) to pursue the "value substitute" of the original collateral – such as insurance payouts for damaged goods or, as in this case, the proceeds from the resale of goods.

- The "Attachment Before Payment or Delivery" Requirement: The critical proviso in Article 304(1) mandates that the preferential right holder must attach these proceeds before they are paid to the debtor or the substitute thing is delivered to the debtor. This case deeply explores the meaning and effect of this requirement in the context of intervening actions by other creditors.

- Competing Creditor Claims: The judgment provides clarity on the hierarchy of rights when a preferential right holder exercising subrogation clashes with general creditors who have made prior provisional attachments.

The Theoretical Underpinnings: "Specificity Maintenance" vs. "Priority Preservation"

The Supreme Court's reasoning touches upon a long-standing theoretical debate regarding the purpose of the "attachment" requirement for subrogation:

- "Specificity Maintenance Theory" (Tokuteisei Iji Setsu): This view, generally favored by legal scholars, posits that a security interest (like a preferential right) is fundamentally a right to the value embodied in the collateral. When the collateral is transformed into proceeds (e.g., a resale price claim), the security interest naturally extends to these proceeds because they represent the same underlying value. The "attachment" requirement, from this perspective, serves merely to maintain the specificity of these proceeds, preventing them from being paid out to the debtor and commingling with their general assets, thus becoming untraceable. Under this theory, subrogation should generally be possible as long as the proceeds have not actually been paid to the debtor and lost their identifiable character.

- "Priority Preservation Theory" (Yūsenken Hozen Setsu): This older view, sometimes associated with traditional judicial interpretations, saw subrogation as a more exceptional legal remedy rather than a natural extension of the security right. It considered the "attachment" as a necessary act to "perfect" the right of subrogation against third parties, effectively giving public notice of the preferential right holder's claim against the specific proceeds. If other third parties (like general attaching creditors) established their claims against the proceeds before the preferential right holder completed this "perfection" via their own attachment, the right of subrogation would be defeated.

The Supreme Court in its 1985 judgment appeared to adopt a nuanced position that drew from both, but with a clear leaning towards allowing the preferential right holder to act unless more definitive third-party rights had intervened. It emphasized that attachment preserves specificity and protects certain third parties from unforeseen losses. The crucial point was that a mere provisional attachment by a general creditor did not create the kind of definitive third-party right or loss of specificity that would preclude a subsequent exercise of subrogation by a creditor with a statutory priority. The Court identified actual payment to the debtor or the acquisition of the claim (e.g., by assignment to a third party or an effective assignment order in favor of another creditor) as the more critical cut-off points.

Distinction from Mortgage Subrogation (A Later Refinement)

It is important to note a subsequent development in Japanese law that refined the understanding of this 1985 judgment. At the time it was delivered, its reasoning was often considered applicable to subrogation under various security interests, including mortgages.

However, a later Supreme Court judgment on January 30, 1998, established a somewhat different rule for mortgage subrogation. It held that a mortgagee could exercise subrogation over, for example, rental income from the mortgaged property, even if that rental income claim had already been assigned to a third party (provided other conditions were met). The primary justification for this distinction was the robust public notice provided by mortgage registration under the Civil Code and the Real Property Registration Act. The Court reasoned that the existence of a registered mortgage puts the world on notice of the mortgagee's potential claim over proceeds arising from the property.

In contrast, statutory preferential rights for the sale of movables, like the one X Corp. held, generally lack a formal system of public registration for the underlying preferential right itself. This lack of initial publicity for the preferential right means that its power to subrogate against proceeds is somewhat more limited when third parties have already acquired rights in those proceeds. The Supreme Court explicitly recognized this distinction in a 2005 judgment (Supreme Court, February 22, 2005), which held that once a resale proceeds claim (targeted by a preferential right for sale of movables) has been assigned to a third party and that assignment perfected against other claimants, the holder of the preferential right can no longer exercise subrogation against it. This confirmed that the presence or absence of a public notice mechanism for the underlying security right is a key factor in determining the strength of its subrogation power against third-party acquirers of the target claim.

Thus, the 1985 judgment discussed here is now understood to be a leading authority specifically concerning the subrogation of statutory preferential rights for the sale of movables, highlighting its distinct characteristics compared to subrogation under security interests like mortgages that possess stronger公示 (public notice) attributes.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of July 19, 1985, delivered an important victory for holders of statutory preferential rights for the sale of movables. It clarified that such a creditor can validly exercise their right of subrogation over resale proceeds even if general creditors have already placed provisional attachments on those same proceeds. The ruling emphasizes that the critical threshold for cutting off this right of subrogation is generally the actual payment of the proceeds to the debtor or the definitive acquisition of the claim by a third party, rather than merely a prior, non-priority provisional attachment. This decision provides a crucial measure of protection for sellers who rely on these statutory preferential rights, ensuring that their priority is not easily defeated by the preliminary actions of general creditors, thereby bolstering the security function of these unique Japanese legal instruments.