Race to Perfection: Japanese Supreme Court on Priority Between General Creditor's Rent Attachment and Later-Registered Mortgage

Date of Supreme Court Decision: March 26, 1998

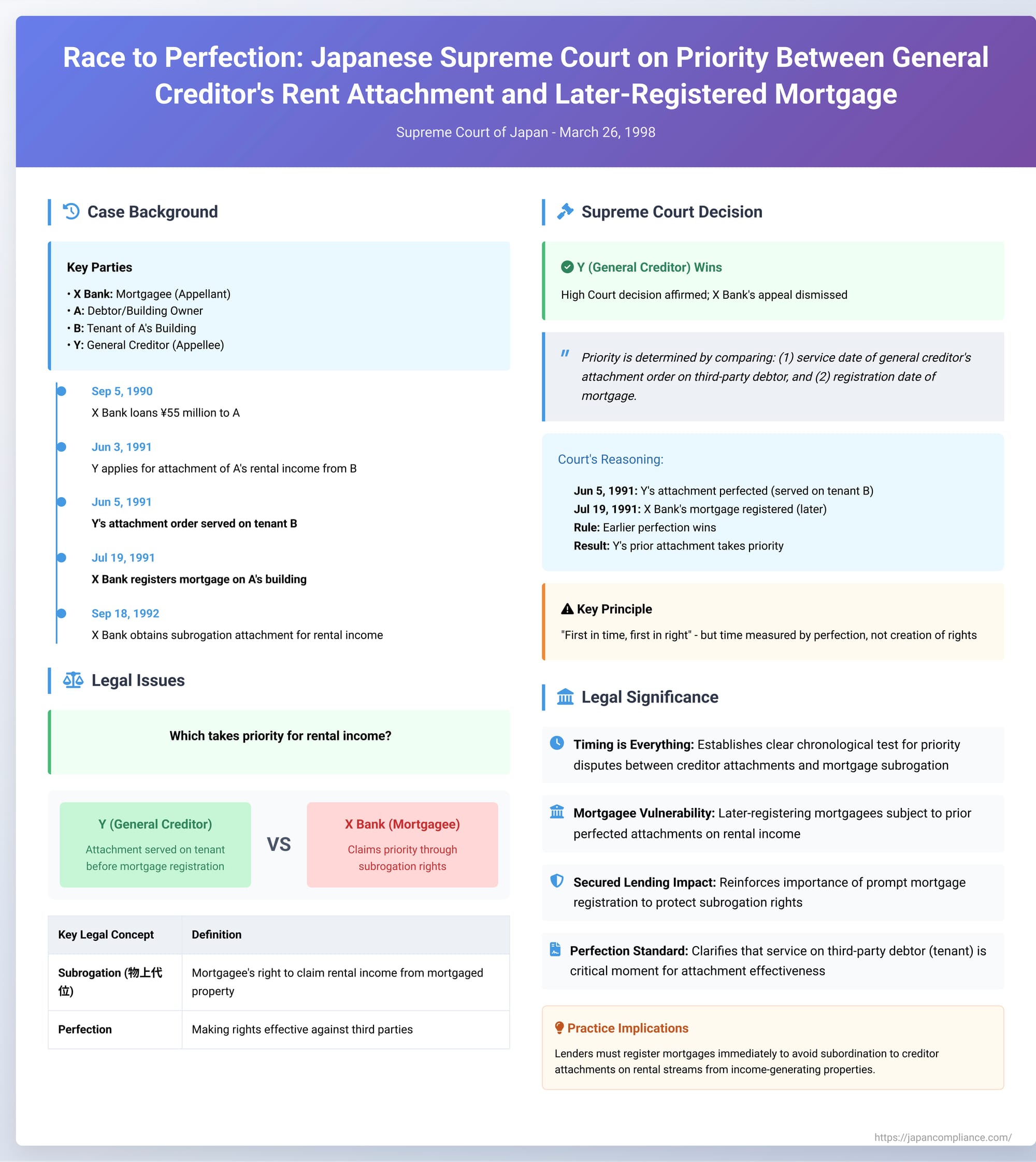

In the realm of debt recovery and secured transactions, the timing of legal actions to perfect rights is often crucial in determining priority among competing creditors. A significant ruling by the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on March 26, 1998 (Heisei 6 (O) No. 1408), addressed a common conflict: the priority struggle between a general creditor who attaches rental income from a property and a financial institution that subsequently registers a mortgage on that same property and then seeks to claim the same rental income through its right of subrogation. This decision provides a clear benchmark for resolving such disputes, emphasizing the importance of the chronological order of perfecting these competing claims.

The Factual Timeline: A Contest for Rental Income

The dispute involved X Bank, the mortgagee; A, the debtor and owner of a building; B, the tenant in A's building; and Y, a general creditor of A. The sequence of events unfolded as follows:

- Y's (General Creditor) Action: On June 3, 1991, Y, holding an enforceable notarial deed against A, applied to the Chiba District Court (Matsudo Branch) for an attachment of A's claim against B for rental income from the building, covering rents due from July 1991 onwards. The court granted this attachment.

- June 5, 1991: Crucially, Y's attachment order was served on B, the tenant (and thus the third-party debtor with respect to the rental payments owed to A). This service is a key moment for the attachment to take effect against the third-party debtor.

- June 13, 1991: Y's attachment order was also served on A, the debtor-landlord.

- X Bank's Loan and Subsequent Mortgage Registration:

- On September 5, 1990, X Bank had initially loaned ¥55 million to A.

- On July 19, 1991, as additional security for this and other dealings, X Bank had A execute a mortgage (specifically, a neteitōken, a type of revolving or floating charge mortgage commonly used in Japan) over the building A owned. The mortgage was registered on this date, securing obligations up to a maximum of ¥59 million. Critically, this mortgage registration occurred after Y's attachment order for the rental income had already been served on the tenant, B.

- A's Default and X Bank's Subrogation Attempt: A subsequently defaulted on its loan repayments to X Bank (from April 5, 1991, onwards). X Bank, after notifying A of the acceleration of the debt due to the default, moved to exercise its rights under the mortgage. It applied to the Tokyo District Court to exercise its right of subrogation (物上代位 - butsujō daii) – a mortgagee's right to claim proceeds or fruits generated by the mortgaged property, such as rent – against A's rental income claim from B, specifically for rents due from September 1992 onwards.

- On September 18, 1992, the Tokyo District Court granted X Bank's application and issued an attachment order for this rental income, up to X Bank's secured amount of ¥59 million.

- Deposit of Rent and Distribution Dispute: Faced with these competing attachment orders (Y's original one and X Bank's later one), the tenant, B, deposited the rental income with the court. In the subsequent distribution proceedings conducted by the Chiba District Court (Matsudo Branch, which handled Y's initial attachment), the court distributed the deposited funds (after deducting procedural costs) pro rata between X Bank and Y, based on their respective notified claim amounts.

X Bank disagreed with this pro rata distribution, contending that its mortgage gave it a priority right to the rental income over Y, whom X Bank viewed as a mere general creditor. X Bank then filed a lawsuit seeking the return of the funds Y had received from the distribution, claiming unjust enrichment.

The court of first instance sided with X Bank, recognizing its priority. However, the High Court reversed this, ruling in favor of Y. The High Court reasoned that X Bank had registered its mortgage after Y’s attachment order on the rental income had been served on the tenant. Therefore, in the contest between X Bank and Y for this specific rental income, Y’s prior perfected attachment should prevail. X Bank appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Pronouncement: Timing of Perfection is Everything

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of March 26, 1998, affirmed the High Court's decision and dismissed X Bank's appeal. The Court laid down a clear rule for determining priority in such scenarios:

The Core Holding: When a general creditor's attachment of a claim (such as rental income) and a mortgagee's subsequent attachment of the same claim based on its right of subrogation are in competition, their relative priority is determined by comparing two critical dates:

- The date of service of the general creditor's attachment order on the third-party debtor (the tenant, in this case).

- The date of registration of the mortgage.

The Rule Applied: If the service of the general creditor's attachment order on the third-party debtor occurs before the mortgage is registered, the mortgagee cannot assert a priority claim to the funds captured by that general creditor's attachment. The prior perfection of the general creditor's attachment gives it precedence over the later-perfected mortgage with respect to the specific proceeds in question.

Application to the Case: In this instance, Y's attachment order was served on the tenant B on June 5, 1991. X Bank's mortgage on the building was registered later, on July 19, 1991. Because Y's attachment on the rental income was perfected (via service on the tenant) before X Bank's mortgage was registered, X Bank could not claim priority over Y for the rental income already subject to Y's effective attachment. Therefore, X Bank was not entitled to a preferential distribution from those funds.

Underlying Legal Principles and Implications

This Supreme Court decision reinforces several fundamental principles of Japanese civil execution and property law:

- Perfection of Rights is Key: For any right or claim to be effectively asserted against third parties, it generally needs to be "perfected" through legally prescribed means.

- For a general creditor's attachment of a monetary claim (like rent owed by a tenant to a landlord), the attachment typically becomes effective against the third-party debtor (the tenant) and creates a prohibition on the debtor-landlord from disposing of the claim upon service of the attachment order on that third-party debtor. This act of service is a critical moment of perfection for the attachment.

- For a mortgage (a real right or bukken), registration in the official property register is the standard method of perfection (対抗要件 - taikō yōken). Registration makes the mortgage opposable to third parties, including other creditors or subsequent purchasers of the property.

- The Mortgagee's Right of Subrogation to Rent: Japanese law (Civil Code Article 372, referencing Article 304 in its then-current form) allows mortgagees to exercise a right of subrogation against the proceeds or fruits of the mortgaged property, which expressly includes rental income. This right was firmly established by a landmark Supreme Court decision in 1989 (Heisei 1.10.27), allowing mortgagees to look to rental streams for satisfaction, particularly when the property value itself might be insufficient. However, the priority of this subrogation right against other claimants is not absolute and depends on factors including the perfection of the mortgage itself.

- "First in Time, First in Right" Based on Perfection: The Supreme Court's 1998 decision effectively applies a "first in time, first in right" principle, but the "time" is measured by the moment each competing claim was perfected against third parties with respect to the specific asset in question—the rental income. Y, the general creditor, perfected its claim on the future rental stream via service of its attachment order on the tenant before X Bank perfected its mortgage (which would give it a basis to claim that same rent via subrogation) via registration.

- Consequences for the Later-Registering Mortgagee: A mortgagee who registers their mortgage after a general creditor has already validly attached the rental income from the mortgaged property finds their subrogation right to that already-attached rent subordinated. The mortgagee, in essence, acquires their security interest in the property subject to the prior, perfected encumbrance on its rental income, at least until the general creditor's claim is satisfied or the attachment is otherwise released.

- Impact on Secured Lending Practices: This ruling has significant implications for secured lending. It underscores the importance for lenders (like X Bank) to ensure prompt registration of their mortgages. Any delay in registration creates a window of vulnerability where other creditors of the property owner might attach the rental income, thereby diminishing the value of the mortgagee's collateral, particularly for income-generating properties where the rental stream is a key component of the security. Lenders need to be aware that their claim to future rents via subrogation will generally not leapfrog a general creditor's attachment that was perfected before the mortgage itself was registered.

- Regarding the Unjust Enrichment Claim: The lawsuit was framed as an unjust enrichment claim by X Bank to recover the funds Y received from the distribution. Given the Supreme Court's determination that Y had priority, Y's receipt of the distributed funds was not "unjust," as it was in accordance with the established legal priorities. The commentary accompanying the case also references other Supreme Court jurisprudence on when a creditor who does not properly object to a distribution plan during the execution proceedings can later bring an unjust enrichment claim. While not the central point of this specific appeal's ratio decidendi, it highlights the procedural context within which such priority disputes are often finally resolved.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's March 26, 1998, decision provides a clear and pragmatic rule for resolving priority conflicts between a general creditor's attachment of rental income and a mortgagee's later-perfected security interest. By focusing on the chronological order of two key events—service of the general creditor's attachment order on the third-party tenant and the registration of the mortgage—the Court established a readily ascertainable standard. This judgment serves as a critical reminder to secured lenders of the paramount importance of timely mortgage registration to safeguard their ability to exercise rights, such as subrogation over rental income, against competing claims from other creditors of the borrower. It reinforces the fundamental role of public registration systems in establishing certainty and priority in property-related rights.