Punitive Damages and Japanese Public Policy: Supreme Court Draws the Line on Enforcing Foreign Judgments

Date of Judgment: July 11, 1997

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

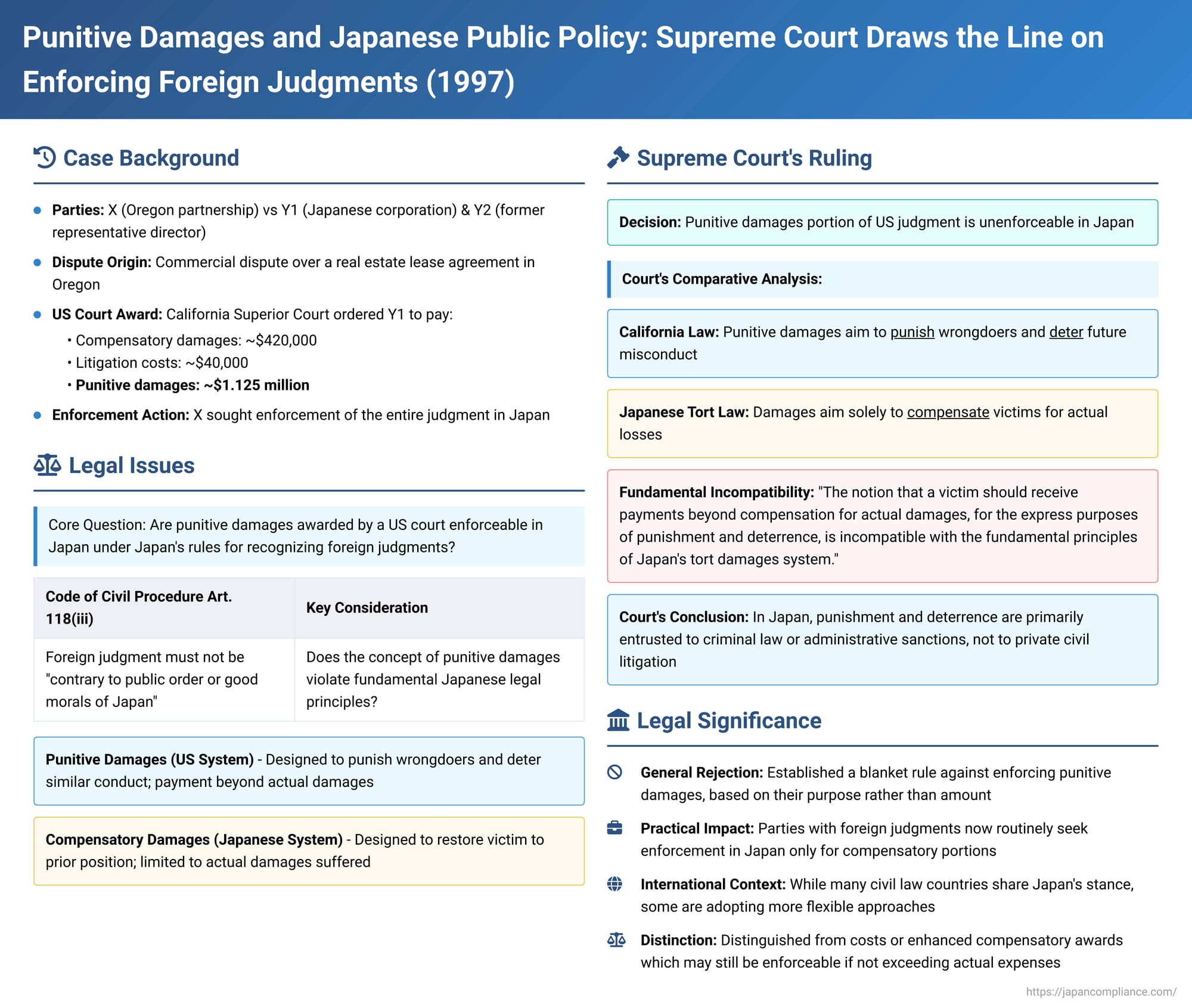

When a party wins a monetary judgment in a foreign court, they often seek to have that judgment recognized and enforced in other countries where the defendant may have assets. However, domestic courts will typically refuse to enforce a foreign judgment if it fundamentally clashes with their own legal system's core principles or "public policy." A landmark Japanese Supreme Court decision on July 11, 1997, addressed this issue head-on in the context of a U.S. judgment that included a substantial award of punitive damages (懲罰的損害賠償 - chōbatsuteki songai baishō), clarifying Japan's stance on enforcing such awards.

The Factual Background: A U.S. Judgment with a Punitive Sting

The case stemmed from a commercial dispute involving Japanese and U.S. entities:

- X (Plaintiff): An Oregon partnership in the United States, established for purposes including facilitating the entry of a U.S. subsidiary (A Corp.) of a Japanese company (Y1) into an industrial park in Oregon.

- Y1 (Defendant): A Japanese corporation.

- Y2 (Defendant): A former representative director of Y1.

- A Corp.: A U.S. California corporation, a subsidiary of Y1.

- B Corp.: An Oregon corporation established by members of X.

- The Underlying U.S. Dispute: A Corp. and B Corp. had entered into a real estate lease agreement in Oregon. Disputes arose, leading A Corp. to sue B Corp. in a California court, seeking a declaration that the lease was invalid. A Corp. also sued X and its members for damages, alleging fraudulent acts. X and B Corp. counterclaimed, seeking performance of the lease from A Corp. and, alternatively, damages from Y1 and Y2 for their alleged fraudulent conduct.

- The California Court Judgment ("Foreign Judgment"): The California Superior Court, while finding the lease agreement not legally binding, ruled in favor of X on its alternative counterclaim. It ordered Y1 and Y2 to pay X:

- Compensatory damages of approximately $420,000.

- Litigation costs of approximately $40,000.

- Crucially, the California court also ordered Y1 (the Japanese corporation) to pay X an additional sum of approximately $1.125 million in punitive damages.

- This Foreign Judgment became final after appeals in the U.S. were dismissed.

- Enforcement Action in Japan: X then sought an enforcement judgment (執行判決 - shikkō hanketsu) from the Japanese courts to enforce the monetary awards in the Foreign Judgment against Y1 and Y2 in Japan.

The Tokyo District Court and the Tokyo High Court both refused to recognize and enforce the punitive damages portion of the U.S. judgment, leading X to appeal to the Supreme Court concerning this refusal.

The Core Legal Question: Is the Punitive Damages Portion of the U.S. Judgment Enforceable in Japan?

The central issue before the Supreme Court was whether the award of punitive damages by the California court was contrary to Japan's public policy and therefore unenforceable in Japan under its rules for recognizing foreign judgments.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Punitive Damages Violate Japanese Public Policy

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal regarding the punitive damages awarded against Y1, affirming that this portion of the U.S. judgment was indeed contrary to Japanese public policy and thus unenforceable. (X's appeal regarding Y2 was dismissed on procedural grounds not directly related to the punitive damages issue).

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

1. Framework for Recognizing Foreign Judgments (CCP Article 118):

The Supreme Court began by noting that for a foreign court judgment to be recognized and enforced in Japan, it must satisfy the conditions set out in Article 118 of Japan's Code of Civil Procedure (CCP) (referring to the old CCP Article 200, the provisions of which are substantively similar to the current Article 118). One of these crucial conditions, stipulated in Article 118(iii) (formerly Art. 200(iii)), is that the content of the foreign judgment must not be contrary to the public order or good morals (公の秩序又は善良の風俗 - kō no chitsujo mata wa zenryō no fūzoku) of Japan.

The Court clarified that simply because a foreign judgment is based on a legal concept or system not adopted in Japan does not automatically mean it violates this public policy condition. However, if the foreign judgment is found to be incompatible with the fundamental principles or basic ideals of Japan's legal order, then it must be considered contrary to public order.

2. Nature of Punitive Damages vs. Japanese Tort Law Principles:

The Supreme Court then conducted a comparative analysis:

- Punitive Damages under California Law: The Court understood that the system of punitive damages in California is designed to punish a wrongdoer who has acted with malice or egregious misconduct and to deter similar conduct in the future. This is achieved by ordering the wrongdoer to pay a sum in addition to the compensation for the actual damages suffered by the victim. The Court found that the purpose of such punitive damages is, therefore, more akin to fines or other criminal penalties in the Japanese legal system.

- Japanese Tort Damages System: In stark contrast, Japan's system of awarding damages for torts (不法行為 - fuhō kōi) is fundamentally compensatory. Its primary objective is to assess the actual loss suffered by the victim in monetary terms and to have the wrongdoer pay this amount to restore the victim, as far as possible, to the position they would have been in had the tort not occurred. The Japanese system does not aim to punish the wrongdoer or to achieve general deterrence as a primary goal.

While an award of compensatory damages might incidentally have a punitive or deterrent effect on the wrongdoer, the Supreme Court viewed these as merely reflexive or secondary consequences. This is fundamentally different from the punitive damages system, where punishment and general deterrence are the inherent objectives.

The Court noted that in Japan, the imposition of sanctions for punishment and the deterrence of future wrongful acts are primarily entrusted to criminal law or administrative sanctions, not to private civil litigation between parties.

3. Fundamental Incompatibility with Japanese Legal Principles:

Based on this comparison, the Supreme Court concluded:

- The notion that, in a dispute between private parties arising from a tort, the victim should be entitled to receive payments from the wrongdoer that go beyond compensation for actual damages, for the express purposes of punishment and general deterrence, is incompatible with the fundamental principles or basic ideals of Japan's tort damages system.

4. Result: Punitive Damages Portion of U.S. Judgment Unenforceable:

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the portion of the U.S. Foreign Judgment ordering Y1 to pay punitive damages "for the sake of example and by way of punishing" Y1, in addition to compensatory damages and litigation costs, was contrary to Japan's public order. As such, this part of the foreign judgment could not be recognized as having effect in Japan and was therefore unenforceable.

Significance and Implications

This 1997 Supreme Court decision established a clear and strong precedent in Japan regarding the enforceability of foreign punitive damage awards:

- General Rejection Based on Purpose: The ruling indicates a general refusal to enforce the punitive component of foreign judgments, based on the fundamental difference in purpose between punitive damages (punishment/deterrence) and Japan's compensatory approach to tort liability. This was not a decision based on the specific amount of the punitive award in this case being excessive, but rather on the incompatibility of the concept of punitive damages with Japanese legal principles.

- Practical Consequences for Litigants: Following this decision, it became standard practice for parties holding foreign judgments that include both compensatory and punitive damages to seek enforcement in Japanese courts only for the compensatory (and costs) portions. The Supreme Court has subsequently reaffirmed this position.

- Academic Discussion: The decision has been the subject of academic analysis. Professor Elbalti Bérenger's commentary notes that while the Supreme Court did not explicitly discuss whether a punitive damages award even qualifies as a "foreign court judgment" in a civil matter (some argue its penal nature makes it quasi-criminal), its direct move to a public policy analysis implies it likely considered it eligible for recognition prima facie, only to be barred by public policy. Criticisms included whether a blanket rejection of the system was appropriate rather than a case-by-case analysis of the result, and whether such a stance might unduly limit flexibility in international cases.

- Distinction from Costs or Enhanced Compensatory Awards: It is important to distinguish this rejection of punitive damages from the enforcement of other types of foreign monetary awards. For instance, as noted in the commentary, a separate Supreme Court case (from 1998, concerning a Hong Kong costs order - case 94 in this series) allowed the enforcement of a foreign costs order that included full attorneys' fees calculated on an "indemnity basis." Even though this might have involved an element of "punitive evaluation" of a party's conduct, it was deemed enforceable because the amount did not exceed actual expenses incurred and was fundamentally aimed at cost recovery, not punishment beyond actual loss.

- International Trends: The commentary also points to an evolving international landscape. While traditionally many civil law (Continental European) countries shared Japan's reluctance to enforce punitive damages, some have shown a trend towards more flexible approaches, potentially enforcing such awards if the amount is not deemed grossly excessive or unreasonable. This reflects a broader tendency to give greater deference to foreign judgments where possible.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1997 decision remains a cornerstone of Japanese law on the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments. It clearly articulates that punitive damage awards, due to their inherent purpose of punishment and general deterrence rather than pure compensation, are considered contrary to the fundamental principles of Japan's private law system and thus violate Japanese public policy. This stance establishes a significant limitation on the enforceability of certain types of monetary awards from common law jurisdictions within Japan, emphasizing the primacy of the domestic legal order's core tenets when confronted with foreign legal concepts that differ fundamentally in their objectives.