Public School Teacher's Liability: A 1987 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Educational Activities as "Exercise of Public Power"

Date of Judgment: February 6, 1987

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

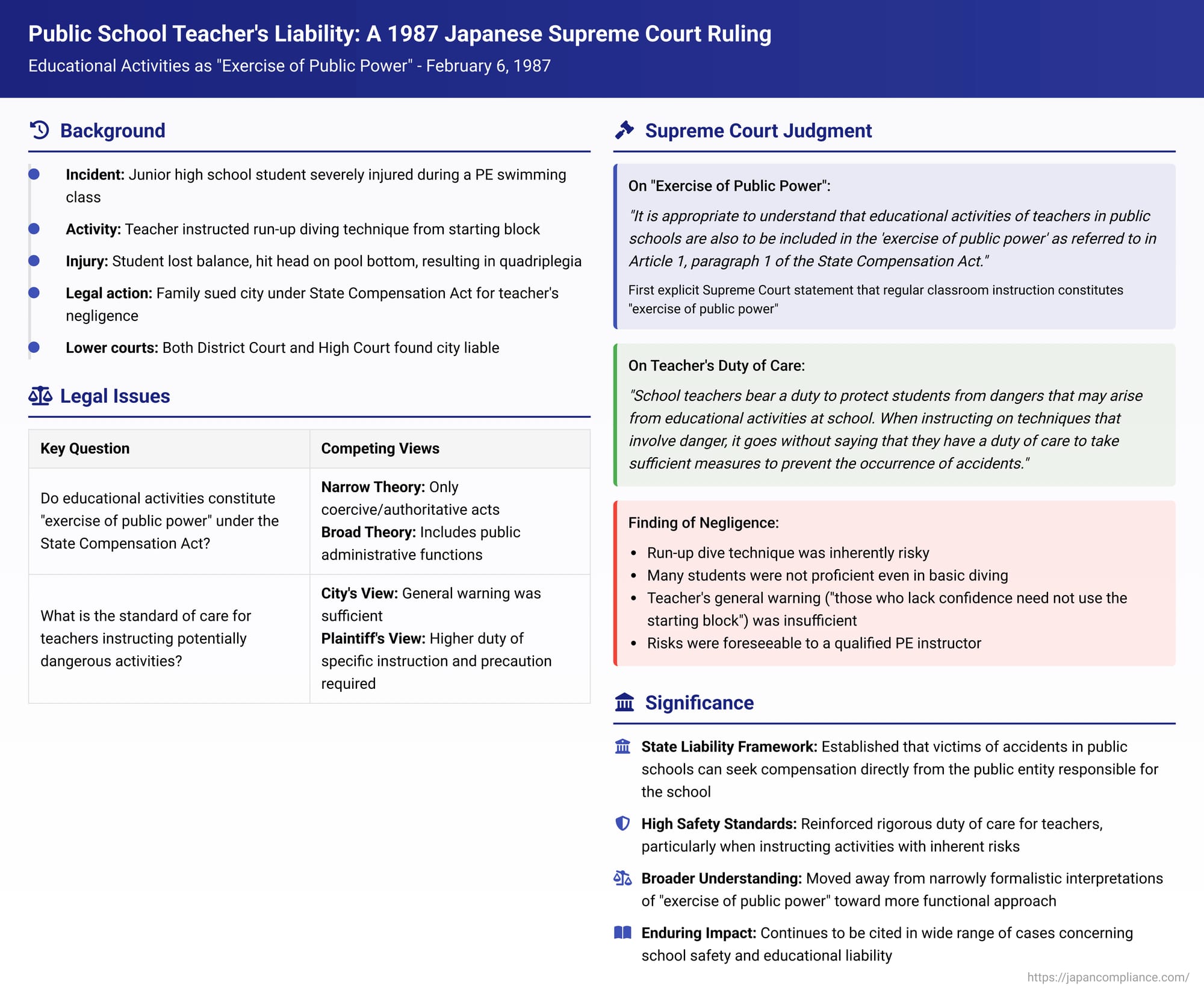

On February 6, 1987, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a tragic case involving a severe injury sustained by a junior high school student during a physical education class. This decision addressed two critical legal questions: firstly, whether the educational activities conducted by a teacher in a public school fall under the definition of "exercise of public power" for the purposes of state compensation liability under Japan's State Compensation Act; and secondly, the scope and nature of a teacher's duty of care to students, particularly when instructing activities that carry inherent risks. The ruling is notable for being the first explicit affirmation by the Supreme Court that the educational activities of public school teachers are indeed included within the "exercise of public power," and for its strong reinforcement of the high duty of care owed by educators to ensure the safety of their students.

I. The Tragic Accident: A Diving Lesson Gone Wrong

The case arose from a devastating accident that occurred during a routine physical education class at a municipal junior high school.

The Setting and Participants:

The incident took place during a swimming lesson for third-year students at a junior high school operated by Y City. The class was being conducted at the school's swimming pool under the supervision and instruction of Teacher A, the physical education instructor responsible for the class.

The Activity: Diving Practice:

The specific activity during which the accident occurred was diving practice. Teacher A was providing instruction to the students on diving techniques.

The Sequence of Instruction Leading to the Accident:

- Teacher A initially provided instruction on diving into the pool from a stationary position, presumably from the edge of the pool or a starting block without any prior movement.

- According to the findings, Teacher A, believing that many students were not yet sufficiently proficient even with these stationary dives and attributing this perceived lack of skill to a weak leg push during take-off, decided to progress to a more advanced and potentially more hazardous diving technique. This involved having the students perform a dive from the starting block after taking a two- to three-step run-up.

- It was alleged by the plaintiffs, X (the injured student and his family), that while Teacher A did inform the students that those who lacked confidence were not required to use the starting block for this run-up dive, A provided no further specific instructions, adequate warnings about the particular risks involved, or detailed safety precautions concerning the proper execution of this specific run-up diving method.

The Accident Involving Student X1:

- X1, a third-year student who was also an active member of the school's swimming club (and thus might have been perceived by himself or others as being more capable in aquatic activities), followed Teacher A's instructions to perform the run-up dive from the starting block.

- Tragically, during the execution of this dive, X1 lost his balance while in mid-air. As a result, he entered the water in an almost vertical position, headfirst, and struck his head with great force on the bottom of the pool.

The Severe and Permanent Consequences:

- The impact caused X1 to suffer catastrophic and life-altering injuries. He sustained a fracture of the fourth cervical vertebra, which in turn led to severe damage to his spinal cord.

- These injuries resulted in permanent quadriplegia (paralysis affecting all four limbs). The paralysis was so profound that X1 was rendered unable to move independently on the floor or even transfer himself to a wheelchair without assistance, indicating a very high level of debilitating impairment.

The Lawsuit for Damages:

Following this devastating accident, X1, along with his parents (X2 and X3) and his younger sibling (X4), initiated a lawsuit against Y City (the public entity responsible for operating the municipal junior high school). They sought over JPY 170 million in damages, basing their claim on Article 1 of Japan's State Compensation Act, which governs the liability of the state or public entities for damages caused by the negligence of public officials in the exercise of public power.

II. Lower Court Proceedings: Affirming Liability

The case proceeded through the District Court and High Court, both of which found the city liable.

Yokohama District Court (First Instance):

- Defining "Exercise of Public Power": A pivotal legal issue from the outset was whether Teacher A's actions in conducting the PE class fell under the definition of "the exercise of public power" as stipulated in Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act. The Yokohama District Court adopted a broad interpretation of this crucial phrase. It defined "exercise of public power" to include "all activities of the state or local public entities based on their authority, not limited to power-asserting actions involving a superior will, but encompassing all activities except purely private economic transactions and the installation and management of public structures (which are covered by Article 2 of the same Act)". Applying this broad definition, the District Court held that educational activities conducted within a municipal junior high school, being an integral part of the city's overall educational administration and utilizing a facility managed by the city, were clearly not "purely private actions" and therefore constituted an "exercise of public power" under the Act.

- Finding of Negligence on the Part of Teacher A: The District Court found that Teacher A, in his role as an instructor, had a high duty of care to prevent accidents when teaching students, particularly when the instruction involved a potentially dangerous activity like diving. The court concluded that Teacher A had breached this duty of care and was therefore negligent in his supervision and instruction.

- Award of Damages: Based on these findings, the District Court awarded substantial damages. Approximately JPY 134 million was awarded to X1 for his severe injuries and resulting disabilities. Compensation was also awarded to his parents, X2 and X3.

Tokyo High Court (On Appeal by Y City):

- Y City appealed the District Court's decision to the Tokyo High Court. The High Court largely upheld the lower court's finding of liability, although it did make a slight reduction in the amount of compensation awarded to X1, by about JPY 10 million.

- Confirmation of Teacher's Negligence: The High Court affirmed the core finding that Teacher A had breached his duty of care. It specifically noted that the run-up dive method that Teacher A had instructed the students to perform was not a technique found in standard swimming instruction manuals for junior high school physical education classes at that time. The court recognized that this particular method carried a significant inherent risk, making it "extremely difficult" for students, especially those not yet fully proficient, to maintain proper aerial posture and control during the dive. This difficulty, in turn, significantly increased the danger of a hazardous, uncontrolled entry into the water.

- Foreseeability of Harm and Inadequate Instruction: The High Court further found that Teacher A, as a qualified physical education instructor responsible for teaching diving, should have been able to fully foresee the dangers associated with the run-up dive method he was promoting. Despite this foreseeability, the court concluded, Teacher A proceeded with this hazardous instruction without providing adequate specific guidance, sufficient safety measures, or clear warnings tailored to the particular risks of the run-up dive. This failure to take appropriate preventative action in the face of a foreseeable risk constituted actionable negligence.

Y City, still contesting its liability, appealed the Tokyo High Court's decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

III. The Supreme Court's Definitive Rulings

The Supreme Court of Japan dismissed Y City's appeal, thereby finalizing the finding of liability against the city. In its judgment, the Court provided clear and authoritative pronouncements on two critical legal points that had been central to the case: the classification of educational activities under the State Compensation Act, and the scope of a teacher's duty of care.

A. Educational Activities of Public School Teachers as "Exercise of Public Power"

The Supreme Court explicitly and unequivocally addressed the crucial question of how the educational activities of teachers in public schools should be categorized under Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act.

- The Court declared: "It is appropriate to understand that educational activities of teachers in public schools are also to be included in the 'exercise of public power' as referred to in Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act."

- Significance of this Explicit Declaration: The PDF commentary that accompanies the text of this case highlights the particular significance of this statement. It notes that while previous Supreme Court decisions had implicitly applied Article 1 of the State Compensation Act to accidents occurring in public schools (for instance, in cases involving incidents during extracurricular club activities or during self-study periods where issues of teacher supervision arose), this 1987 judgment marked the first occasion on which the Supreme Court had explicitly and clearly stated that the core educational activities of teachers conducted during regular class instruction fall under the definition of "exercise of public power". The commentary speculates that the specific factual context of this case—an accident that arose directly from a teacher's active instruction during a scheduled class—may have been considered by the Court as a particularly suitable and clear-cut opportunity to make this important pronouncement and remove any lingering ambiguity.

- Context of Legal Theories on "Exercise of Public Power": The PDF commentary provides valuable context by outlining the long-standing academic debate in Japanese legal circles regarding the precise interpretation of the term "exercise of public power". Three main doctrinal theories have been advanced:

- The Narrow Theory (kyōgi-setsu): This theory traditionally restricted the scope of "exercise of public power" to actions that involve a clear assertion of superior governmental will or coercive authority—essentially, power-based administrative actions. It generally excluded non-power administrative activities, purely private economic activities undertaken by the state, and liabilities arising from the installation or management of public structures (as these are specifically covered by Article 2 of the State Compensation Act).

- The Broad Theory (kōgi-setsu): This theory offers a more expansive interpretation. It includes not only power-based administrative actions but also encompasses a wider range of non-power public administrative activities. It generally excludes from Article 1 only purely private economic activities and those liabilities falling under Article 2. It is noteworthy that the first instance court (Yokohama District Court) in this very case had explicitly adopted this broad theory in its reasoning.

- The Broadest Theory (sai-kōgi-setsu): This theory takes the most encompassing view, suggesting that Article 1 liability could extend to almost all activities undertaken by the state or public entities, potentially including even their private economic transactions.

- The PDF commentary further notes that while the narrow theory was historically quite influential in Japanese administrative law, the broad theory gradually gained increasing acceptance in lower court judgments and is now generally considered to be the prevailing view among legal scholars in Japan. Although this specific Supreme Court judgment did not use the occasion to explicitly adopt the "broad theory" in its entirety as a universal principle for all types of non-power state activities, its clear affirmation regarding public school educational activities, and its ultimate upholding of the first instance court's decision (which had been explicitly based on the broad theory), strongly indicates that the Supreme Court does not adhere to a strictly narrow interpretation of "exercise of public power". The precise scope of the term's application to other forms of non-power governmental activities would likely continue to be clarified and refined through the accumulation of future case law.

- Practical Implications of the "Exercise of Public Power" Classification: One of the key practical implications of classifying an activity as an "exercise of public power" under Article 1 of the State Compensation Act, as discussed in the PDF commentary, is that the Act itself applies directly. This Act, unlike Article 715 of the Civil Code (which governs vicarious liability for private employers), does not contain the same provisions for an employer's potential immunity from liability if they can prove they exercised due care in selecting and supervising the employee. (Though it is also noted that such employer immunity under the Civil Code is rarely granted in practice ). Perhaps more significantly for the public officials involved, a long-standing Supreme Court precedent (dating from 1955) generally shields individual public officials (such as Teacher A in this case) from direct personal liability towards the injured party when their actions, performed in their official capacity, fall under Article 1 of the State Compensation Act. Instead of the individual official being sued, the state or the public entity (Y City in this instance) assumes the liability. Thus, by classifying public school educational activities as an "exercise of public power," the Supreme Court effectively brought cases of teacher negligence within this established framework of state (or public entity) liability, rather than exposing teachers to direct personal lawsuits from victims for actions taken in the course of their duties.

B. Teacher's Duty of Care to Protect Students from Harm

The Supreme Court also delivered strong and clear affirmations regarding the existence, nature, and scope of a school teacher's duty of care towards the students under their supervision.

- It stated unequivocally: "School teachers bear a duty to protect students from dangers that may arise from educational activities at school."

- Furthermore, the Court elaborated: "When instructing on techniques that involve danger, it goes without saying that they [teachers] have a duty of care to take sufficient measures to prevent the occurrence of accidents."

- Application of the Duty of Care to the Facts of the Diving Accident: Applying these fundamental principles to the specific circumstances of the diving accident involving X1, the Supreme Court found that Teacher A had clearly breached this duty of care. Its reasoning included the following points:

- The method of diving that involved a run-up, particularly when executed onto a starting block, was recognized as inherently difficult. The Court noted challenges in timing the take-off correctly and accurately setting the take-off point on the block. Errors in executing this complex maneuver could easily lead to a diver losing balance, resulting in an uncontrolled aerial phase and a deep, potentially hazardous entry into the water. This risk associated with the run-up dive technique was deemed to have been "fully foreseeable" by Teacher A, who was responsible for providing diving instruction.

- Crucially, it was established that many of the students in the class were found to be "immature" or not yet proficient even in performing simpler stationary dives. Given this baseline level of student skill, instructing them to attempt the more complex and dangerous run-up dive was, in the Court's view, "extremely dangerous".

- The Supreme Court concluded that Teacher A should have taken specific precautionary measures and exercised careful consideration for student safety, consistent with the findings of the High Court, but had failed to do so adequately. This failure to implement appropriate safeguards in the face of a foreseeable and significant risk constituted a breach of the teacher's duty of care.

- The Court specifically addressed the fact that Teacher A had told the students that those who lacked confidence did not need to use the starting block for the run-up dive. It found this general statement to be insufficient to discharge the teacher's comprehensive duty of care. The Court reasoned that junior high school students, who are still in the process of learning new physical skills and developing their ability to assess risks, could not be expected to fully understand or appreciate the dangers associated with the run-up dive method merely from such a general and non-specific advisory. A more proactive, detailed, and cautionary approach to safety instruction was required from the teacher.

- The Supreme Court thus upheld the consistent findings of the lower courts regarding the negligence on the part of Teacher A, for which Y City, as his employer and the operator of the public school, was held liable under the State Compensation Act. The PDF commentary notes that this 1987 judgment's clear pronouncements on the teacher's fundamental duty to protect students have proven to be influential and have been frequently cited in a variety of subsequent lower court cases. These later cases involve a wide array of school-related incidents, not limited to typical sports accidents during PE classes, but also encompassing a broader range of safety issues and potential harms that can arise within the overall school environment.

IV. Broader Significance and Implications

The 1987 Supreme Court decision in this school accident case carries broader significance for Japanese law, particularly in the realms of state compensation and educational liability.

Clarification of State Liability in the Context of Public Education:

- This judgment is of paramount importance primarily because it clearly and definitively situates the educational activities of teachers employed in public schools within the legal framework of the State Compensation Act, specifically Article 1. By explicitly including these core teaching activities under the rubric of "exercise of public power," the Supreme Court effectively removed any lingering ambiguity on this point. This solidified the principle that public entities (such as cities and prefectures that operate public schools) are directly liable for damages that arise from the negligence of their teacher-employees when that negligence occurs in the course of their official educational duties.

- This clarification has had significant practical implications for how school accident cases involving public schools are subsequently litigated in Japan. It provides a clear legal basis for victims and their families to seek compensation directly from the responsible public entity (the city, prefecture, or national government, depending on the type of school). This avoids the potential complexities and difficulties that might arise if victims were required to pursue claims against individual teachers personally for actions taken within the scope of their official duties.

Reinforcement of High Safety Standards and Teacher Responsibility in Schools:

- The judgment's strong and unequivocal affirmation of a teacher's duty to protect students from foreseeable dangers, particularly when instructing activities that have inherent risks, serves to reinforce the high standards of care that are expected within educational settings in Japan. It underscores the principle that teachers must not only possess the necessary pedagogical skills for instruction but also exercise a significant degree of foresight, implement appropriate and effective safety measures, and provide clear, age-appropriate warnings and guidance to their students in order to prevent accidents.

- The Supreme Court's dismissal of the argument that merely telling students they "didn't have to" perform a dangerous maneuver if they felt unconfident was sufficient to discharge the teacher's duty is particularly telling. This aspect of the ruling highlights a proactive and positive responsibility on the part of educators. It implies that teachers must actively assess the capabilities of their students and the inherent risks associated with the activities they are teaching, and then adapt their instruction and safety protocols accordingly, rather than placing the primary onus of risk assessment and avoidance entirely on students who may be immature or inexperienced.

Impact on the Judicial Interpretation of "Exercise of Public Power":

- While, as the PDF commentary correctly points out, the Supreme Court did not use this particular case as a vehicle to issue a definitive, all-encompassing statement that would formally adopt the "broad theory" of "exercise of public power" for every conceivable type of non-power governmental activity, its specific and explicit inclusion of public school education within this category was, nonetheless, a very significant step. It signaled a clear move away from any overly restrictive or narrowly formalistic interpretation that might have sought to exclude such essential public service functions from the scope of Article 1 state compensation liability.

- This decision encourages a more functional and substantive understanding of "exercise of public power," prompting courts to look at the nature of the activity in question (in this case, a public educational service provided by a state-employed teacher within a state-operated facility) rather than adhering rigidly to older, perhaps outdated, distinctions based on whether the governmental act involved "command and control" in a traditional, coercive administrative law sense. The PDF commentary appropriately suggests that the exact boundaries of this concept for other types of non-power governmental activities will continue to be delineated and shaped by the accumulation of future case law.

Continuing Relevance for School Safety, Educational Policy, and Legal Liability:

- The core principles articulated in this 1987 case regarding a teacher's duty of care and the state's responsibility remain highly relevant in contemporary Japan. As noted in the PDF commentary, lower courts continue to cite this Supreme Court judgment in a wide array of cases that concern student safety and school liability. This indicates the enduring influence of the Court's emphasis on the protective obligations owed by educational professionals and institutions to the students under their charge. The decision likely continues to inform school policies, teacher training, and risk management practices in the educational sector.

V. Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's decision of February 6, 1987, in the case of the tragic junior high school diving accident, stands as a landmark ruling in the intertwined fields of state compensation law and educational liability in Japan. It provided the first explicit and authoritative affirmation from the nation's highest court that the educational activities conducted by teachers in public schools constitute an "exercise of public power" as defined under Article 1 of the State Compensation Act. This crucial classification has the effect of making public entities, such as cities and prefectures, directly liable for damages resulting from the negligence of their teacher-employees during the course of educational duties.

Furthermore, the judgment powerfully reiterated and reinforced the high duty of care that teachers owe to their students, particularly when instructing on activities that carry inherent risks. It underscored the necessity for educators to implement proactive safety measures, provide clear and appropriate guidance, and exercise foresight to prevent accidents. This ruling has undoubtedly had a lasting impact on clarifying the legal responsibilities of public schools and educators in Japan, and it continues to serve as an important reference point in judicial considerations of school safety, teacher negligence, and the scope of state liability in the educational context.