Public Housing, Private Rules: Supreme Court Applies Trust Doctrine to Eviction Case

Judgment Date: December 13, 1984

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

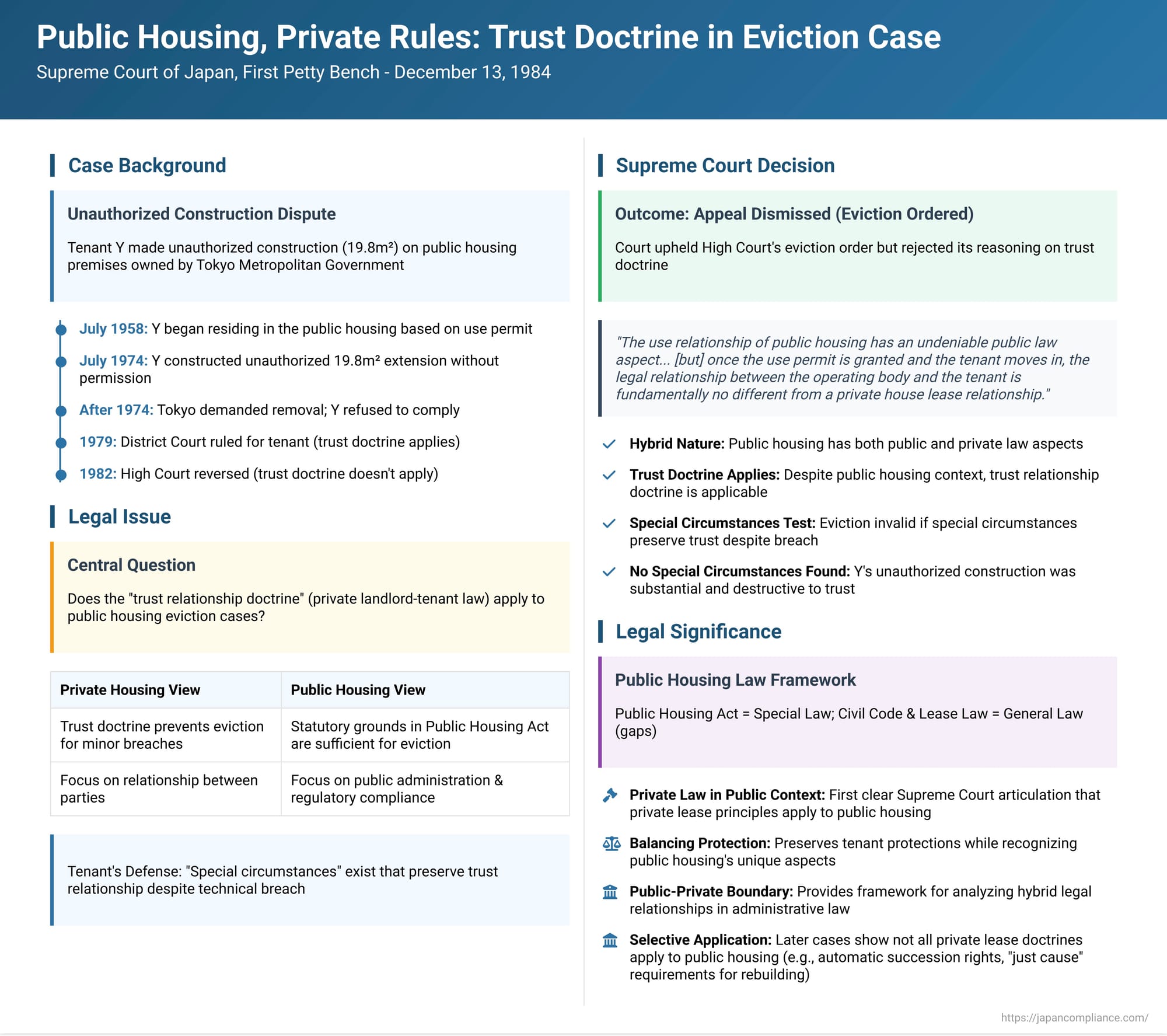

The relationship between tenants and providers of public housing in Japan sits at a fascinating intersection of public administrative law and private contract law. A 1984 Supreme Court decision addressed a key aspect of this interface: Does the "doctrine of trust relationship" (shinrai kankei no hōri), a principle primarily developed in private landlord-tenant law to prevent unfair evictions, apply when a public housing authority seeks to evict a tenant for breaching their agreement, such as by making unauthorized constructions? The Court said yes, offering a nuanced view on how these legal domains interact.

The Unauthorized Extension and the Eviction Lawsuit

The case involved a tenant, Y, who had been residing in public housing ("the Apartment") owned and operated by X, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, since July 1958. His occupancy was based on a use permit granted under the Public Housing Act and relevant Tokyo Metropolitan Government ordinances.

Around July 1974, Y undertook a significant alteration to the property without obtaining X's permission: he constructed an unauthorized building with a floor area of 19.80 square meters on the premises of the Apartment ("the Unauthorized Construction"). X, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, subsequently demanded that Y remove this structure and restore the land to its original condition. When Y failed to comply, X took further action. Citing the Unauthorized Construction as a breach of conditions that constituted statutory grounds for eviction under the Public Housing Act, X revoked Y's use permit for the Apartment and filed a lawsuit seeking Y's eviction and the removal of the unauthorized structure.

In his defense, Y argued that even if the Unauthorized Construction technically constituted a ground for eviction under the law, there were "special circumstances" that made it difficult to conclude that the fundamental trust relationship with X had been destroyed. Therefore, he contended, X's eviction claim was invalid.

Lower Courts Divided: The Trust Doctrine at the Forefront

The case took different turns in the lower courts:

- The Tokyo District Court (First Instance), in its ruling on May 30, 1979, largely sided with the tenant, Y. It held that the legal nature of a public housing use relationship is fundamentally that of a private law lease contract. Therefore, unless specific provisions in the Public Housing Act or local ordinances dictated otherwise, general laws such as the Civil Code and the (now-repealed) House Lease Act should apply. The District Court accepted Y's argument that special circumstances existed which did not negate the trust relationship, and consequently, it partially dismissed Tokyo's claim for eviction.

- The Tokyo High Court (Second Instance), however, reversed this part of the decision on June 28, 1982, and ordered Y's eviction. The High Court reasoned that the trust relationship doctrine, as applied in private leases, was not appropriate for public housing. It pointed out that public housing authorities do not have the freedom to select tenants based on their perceived trustworthiness or suitability for a personal landlord-tenant relationship; rather, tenants are chosen from low-income individuals in genuine housing need, based on specific legal criteria.

Y then appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Balanced Approach

The Supreme Court, on December 13, 1984, dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's outcome (i.e., ordering eviction). However, the Supreme Court significantly disagreed with the High Court's reasoning, particularly its rejection of the trust relationship doctrine.

1. Public Housing: A Hybrid of Public and Private Law

The Supreme Court acknowledged the dual nature of the public housing use relationship. On one hand, it stated that "the use relationship of public housing has an undeniable public law aspect as it concerns the use of a public facility". This public dimension is reflected in the Public Housing Act and related ordinances, which govern aspects like tenant selection through public offerings, eligibility criteria based on income and housing need, fair selection processes conducted by the head of the public housing authority, and the requirement of a formal "use permit" to occupy the dwelling.

On the other hand, the Court emphasized that once this use permit is granted and the tenant moves in, "the legal relationship between the operating body and the tenant is fundamentally no different from a private house lease relationship," despite the overlay of public regulations. The Court found this evident in the Public Housing Act itself, which uses terminology common to private law leases, such as "lease" (chintai), "rent" (yachin), and so on.

2. The Trust Relationship Doctrine: Applicable, But...

Based on this hybrid understanding, the Supreme Court laid out how different laws apply. The Public Housing Act and related ordinances serve as "special laws" that take precedence over the Civil Code and the (then-applicable) House Lease Act. However, where these special laws are silent, the "general laws"—the Civil Code and the House Lease Act—apply in principle.

Crucially, the Supreme Court concluded from this that "the doctrine of trust relationship (shinrai kankei no hōri) is applicable to regulate this contractual relationship". It reasoned that even though the public housing authority has limited freedom in initially selecting tenants, "once the use relationship is established, a legal relationship based on trust exists between the parties".

Therefore, the Court stated, "even if a public housing user commits an act that constitutes statutory grounds for eviction under the Public Housing Act, the head of the operating body cannot revoke the use relationship and demand eviction if there are special circumstances that make it difficult to recognize that the trust relationship with the lessor (the operating body) has been destroyed". The High Court had thus erred in its legal interpretation by completely excluding the applicability of the trust relationship doctrine.

3. No "Special Circumstances" to Save the Tenant This Time

Despite finding the High Court's legal reasoning flawed, the Supreme Court ultimately upheld its decision to evict Y. After affirming the applicability of the trust relationship doctrine, the Supreme Court examined the specific facts of Y's case as determined by the High Court.

The High Court had found that Y's Unauthorized Construction was substantial and not easily restorable to its original state, nor was it conducive to the proper preservation of the Apartment. There was also no evidence that X (Tokyo) had subsequently approved or condoned the unauthorized building. Taking these facts into account, the Supreme Court concluded that even if Y had compelling family circumstances (such as needing more space for growing children, as he had argued), these did not rise to the level of "special circumstances making it difficult to recognize that the trust relationship with X had been destroyed". Therefore, Tokyo's claim for eviction was well-founded.

Deeper Dive: Unpacking the Ruling's Significance

This Supreme Court decision has several important implications for understanding the legal framework governing public housing in Japan.

Public Housing Act as Special Law, Civil Code as General Law:

A key takeaway, though noted by some commentators as being part of the obiter dictum (statements not strictly essential to the decision), was the Supreme Court's first clear articulation that while the Public Housing Act and related local ordinances function as special laws specifically governing public housing, general private laws like the Civil Code and landlord-tenant statutes apply where these special laws have no specific provision. Some scholars have downplayed the "practical significance" of this point, arguing it's natural for special laws to take precedence and for general laws to fill the gaps. Others in civil law have questioned the logic of re-applying a general private law doctrine (trust relationship) to an eviction claim that is itself based on specific grounds laid out in a special public law (the Public Housing Act). Nevertheless, the ruling is now often cited in legal textbooks as an example of how private law contractual principles are modified by, and interact with, special administrative laws.

The Ongoing Dialogue: Public vs. Private Law in Administrative Contexts:

The judgment touches upon the long-standing debate in Japanese administrative law concerning the distinction between "public law" and "private law" relationships. The traditional approach often involved first categorizing a legal relationship as either public or private, with this categorization then determining which set of legal rules applied. For instance, early debates on whether public housing rent could be collected through compulsory administrative measures often hinged on whether the use relationship was considered public or private (with the common understanding leaning towards private).

The current prevailing academic view tends to downplay the significance of this strict public-private dichotomy in the context of applying laws, sometimes even denying the utility of the "public law" concept itself for such purposes. While this Supreme Court decision does refer to the "public law aspect" of public housing use, and some commentators see this as a nod to the traditional dichotomy, its core reasoning for applying the trust doctrine relies more on the fundamental similarities between the established public housing relationship and private leases, as well as the statutory use of private law terminology. Thus, it's unlikely the decision is rigidly premised on an initial public-vs-private law classification.

How "Special" is the Trust Doctrine in Public Housing?

The Supreme Court affirmed the applicability of the trust relationship doctrine—a doctrine designed to protect tenants from eviction for minor breaches by requiring that the breach be grave enough to destroy the landlord-tenant trust. This seems a natural fit for public housing given the ongoing nature of the relationship and the severe impact of eviction on tenants, often vulnerable individuals.

However, this does not mean that all provisions of general landlord-tenant law apply wholesale to every public housing issue. The Court itself has, in other cases, recognized the special nature of public housing. For example:

- A 1987 Supreme Court decision held that the "just cause" requirement (a stringent condition for landlords to refuse lease renewal or terminate a lease under general landlord-tenant law, similar to Article 28 of the current Act on Land and Building Leases) does not apply to evictions from public housing for the purpose of rebuilding dilapidated structures, provided statutory conditions under the Public Housing Act are met.

- A 1990 Supreme Court decision ruled that there is no room to interpret an automatic right for an heir of a deceased tenant to succeed to the public housing use right.

- More recently, a 2017 Supreme Court decision upheld a local ordinance that allowed only relatives who were cohabiting with the tenant of an "improved" public housing unit at the time of their death to continue residing there, finding this provision consistent with relevant housing laws.

These cases illustrate that the application of private law principles is nuanced and determined on a case-by-case basis, considering the specific purposes of both the administrative housing statutes and the relevant private law doctrines. The question of whether the trust relationship doctrine applies with the exact same content and intensity in public housing as in purely private leases, considering the public interest aspects and the specific objectives of public housing, remains a topic for further judicial and academic clarification.

Characterizing "Revocation of Use Permit": Administrative Act or Contract Termination?

The process of entering public housing involves a "use permit," and eviction often involves its "revocation" by the housing authority. The legal characterization of this revocation is important. If it's considered an "administrative disposition" (an official act by an administrative agency creating legal effects), its validity is generally presumed unless challenged and overturned in a specific type of lawsuit (an administrative revocation suit), which has exclusive jurisdiction.

The Supreme Court in this case discussed the trust relationship doctrine within the context of an eviction lawsuit (a civil claim for recovery of property), not an administrative revocation suit. This suggests the Court might be viewing the "revocation of the use permit" more as an act of contract termination (analogous to a landlord terminating a lease) rather than as a formal withdrawal of a beneficial administrative act.

However, even acts that aren't typical administrative orders can sometimes be classified as "administrative dispositions" by examining the overall statutory scheme. Some lower courts have indeed treated public housing use permit revocations as administrative dispositions. If the revocation were viewed as the withdrawal of a beneficial administrative act due to the recipient's fault (the tenant's breach), administrative law principles generally allow for such withdrawal. Yet, even then, general legal principles like "good faith and sincerity" and the "prohibition of abuse of rights" would apply to such an exercise of public power, potentially rendering an overly harsh revocation impermissible.

When the conditions for revocation are, as in this case, specified by law, the issue becomes less about the inherent limits on withdrawal and more about controlling the discretion exercised in effecting the revocation. Even if statutory grounds for revocation are met, the authority must still properly weigh various factors. Judicial review would scrutinize such a decision for violations of general legal principles (like proportionality) and for abuse of discretion (e.g., failing to consider relevant factors or considering irrelevant ones). Since the private law doctrine of trust relationships is itself rooted in principles of good faith and preventing abuse of rights, this administrative law approach to discretionary control might offer a valuable framework for defining the "special circumstances" that could prevent eviction in public housing cases.

Conclusion: A Nuanced Application of Private Law to Public Utility Relationships

The 1984 Supreme Court decision provides a vital clarification on the legal nature of public housing use in Japan. It confirms that while public housing is imbued with public law characteristics and objectives, the day-to-day relationship between the housing authority and the tenant shares fundamental similarities with private leases. Consequently, the trust relationship doctrine, a cornerstone of tenant protection in private law, is applicable. However, the Court also demonstrated that the application of this doctrine is fact-sensitive, and substantial breaches by tenants, like the unauthorized construction in this case, can indeed be deemed destructive of that trust, leading to eviction. This ruling underscores the ongoing judicial effort to balance the public mission of housing provision with the need for fair and predictable rules governing landlord-tenant interactions, even when one party is the state.