Proxy Attendance and Voting at Condominium Board Meetings: A 1990 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: November 26, 1990

Case Number: 1990 (O) No. 701 (Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench)

Introduction

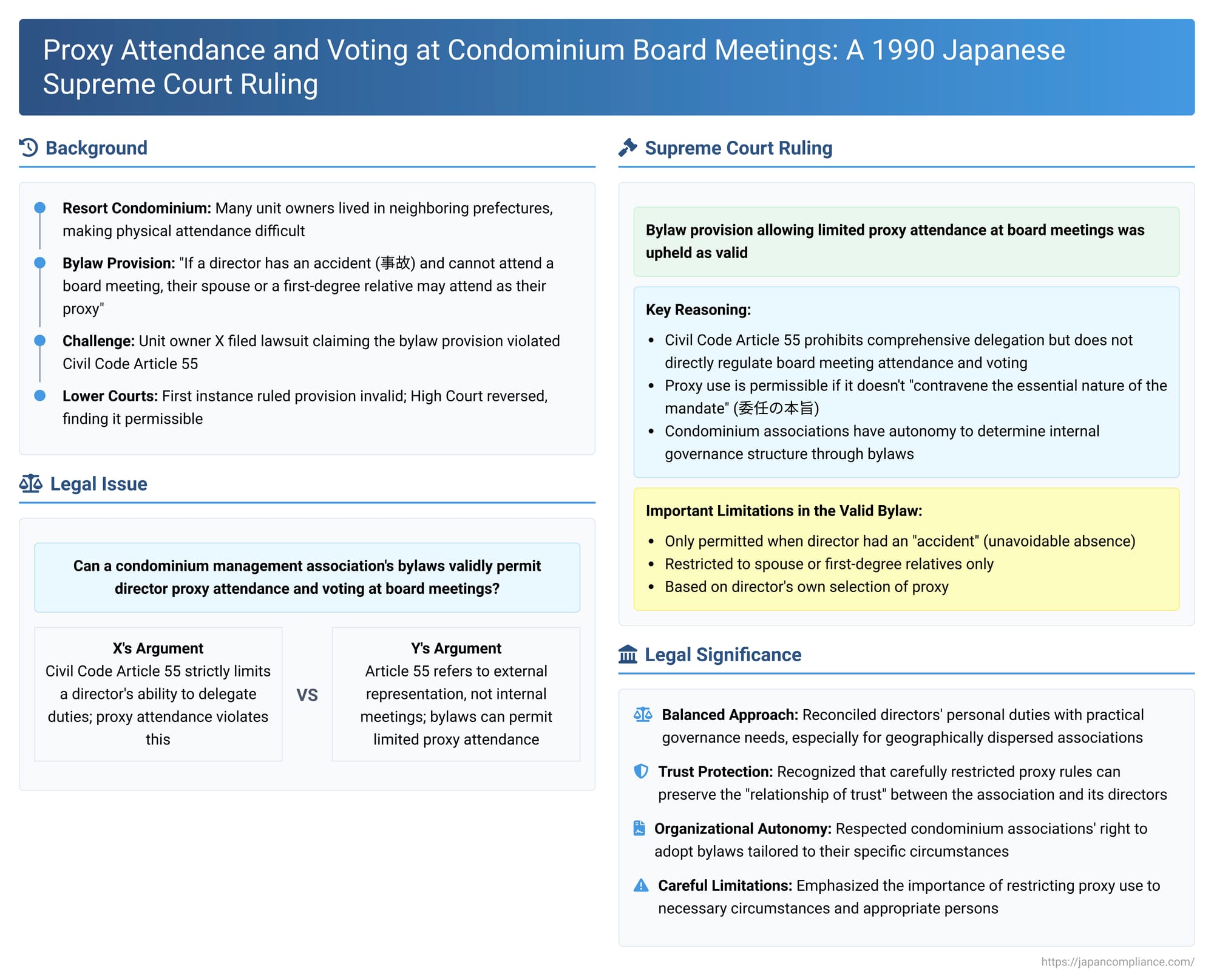

In Japan, particularly with resort condominiums or properties where unit owners may reside at a distance, ensuring active participation in governance can be challenging. Directors of the management association, often unit owners themselves, may find it difficult to attend every board meeting in person. This practical difficulty raises an important legal question: Can a condominium management association's bylaws validly permit a director to appoint a proxy, such as a spouse or close family member, to attend and vote on their behalf at board of directors meetings?

A Supreme Court decision on November 26, 1990, addressed this issue, focusing on the interpretation of relevant Civil Code provisions concerning the delegation of a director's duties and the fundamental nature of the trust relationship between a corporation and its directors.

Facts of the Case

The case involved Y, an incorporated management association (管理組合法人 - kanri kumiai hōjin) of a resort condominium where a significant number of unit owners lived in neighboring prefectures, not locally. Due to the geographical dispersion of its members, physical attendance at meetings could be burdensome.

At an extraordinary general meeting, Y's members adopted a new provision into its bylaws (規約 - kiyaku). This provision stated: "If a director has an accident (事故 - jiko, meaning an unforeseen circumstance or impediment) and cannot attend a board of directors meeting, their spouse or a first-degree relative only may attend as their proxy."

X, a unit owner in the condominium, challenged this bylaw. X filed a lawsuit against Y, seeking a judicial declaration that the general meeting resolution adopting this bylaw provision was invalid. X's primary legal argument was that the provision violated former Article 55 of the Japanese Civil Code. At the time, this Civil Code article was applied to directors of incorporated management associations through Japan's Condominium Ownership Act (specifically, the then Article 47, Paragraph 2; this principle is now reflected in Article 49-3 of the current Condominium Ownership Act). X interpreted former Civil Code Article 55 as strictly limiting a director's ability to delegate their duties, permitting only the delegation of specific acts and prohibiting any broader or more comprehensive sub-delegation of responsibilities, which X argued this proxy provision amounted to.

Lower Court Rulings:

- First Instance Court: The court of first instance sided with X, finding the bylaw provision to be invalid on the grounds that it contravened former Civil Code Article 55.

- High Court (Appellate Court): The High Court reversed the first instance decision. It reasoned that former Civil Code Article 55 was primarily aimed at prohibiting comprehensive sub-agency by a director concerning the corporation's external representational acts. The High Court distinguished the bylaw provision in question, viewing it as pertaining to the corporation's internal decision-making processes (i.e., board meetings) rather than external representation. On this basis, it dismissed X's claim.

X appealed the High Court's ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of November 26, 1990, affirmed the High Court's decision to dismiss X's claim, thereby upholding the validity of the bylaw provision.

The Supreme Court's reasoning unfolded as follows:

1. Interpretation of Former Civil Code Article 55:

The Court first addressed the scope and purpose of former Civil Code Article 55.

- It explained that a corporation's director, while generally representing the corporation in all its affairs, cannot reasonably be expected to personally execute every single task. However, allowing a director to comprehensively delegate all their agency powers to another person would undermine the relationship of trust (信任関係 - shinnin kankei) between the corporation (which selected the director) and that director.

- Therefore, Article 55 was structured to permit a director to delegate to another person only the authority to act as an agent for specific acts of the corporation, and only if such delegation was not otherwise prohibited by the corporation's articles of incorporation, foundational act of endowment, or a resolution of a general meeting. The article effectively prohibited a comprehensive (blanket) delegation of a director's duties.

- Crucially, the Supreme Court stated that Article 55 does not directly regulate the rules concerning attendance and the exercise of voting rights at meetings of a board of directors, particularly in situations where a corporation has multiple directors and has formally established a board of directors as an internal organ.

- Consequently, a bylaw provision that permits proxy attendance and voting at board meetings is not, by virtue of Article 55 alone, immediately rendered illegal.

2. Permissibility of Proxy Use in a Corporation's Internal Meetings:

The Court then laid down a general principle for determining whether proxy attendance and voting are permissible in a corporation's internal decision-making bodies, such as a board of directors:

- This question should be decided by considering whether allowing such proxy use would "contravene the essential nature of the mandate" (委任の本旨に背馳する - inin no honshi ni haichi suru) given by the corporation to its directors.

- This determination requires an examination of:

- The purpose for which the specific decision-making body (e.g., the board of directors) was established within the corporation.

- The nature of the duties and affairs entrusted to that body.

3. Application to Condominium Management Associations:

The Supreme Court then applied these principles to the context of incorporated condominium management associations:

- The Condominium Ownership Act (COA) generally allows the internal governance structure of a management association – including the setup of its executive organs – to be determined by its bylaws, reflecting the principle of organizational autonomy.

- This includes the freedom to decide:

- Whether to have multiple directors.

- Whether to appoint non-representative directors (COA Article 49, Paragraph 4, allows for directors who may not have general representative authority).

- Whether to establish a board of directors if multiple directors are appointed.

- The specific rules for board meeting procedures, such as attendance requirements and methods for exercising voting rights.

- Given this flexibility, the Supreme Court concluded that it is permissible for the bylaws of an incorporated management association to stipulate:

- Whether proxy attendance and voting at board meetings are allowed.

- The specific conditions under which proxies may be used (e.g., when a director is unable to attend for a valid reason).

- The scope of individuals who are eligible to act as proxies.

4. Assessment of the Specific Bylaw Provision in Question:

The Supreme Court then examined the particular bylaw provision adopted by Y:

- It acknowledged that the provision allowed a proxy not only to attend a board meeting but also to exercise the director's voting rights.

- However, the Court emphasized the strict limitations embedded in the provision:

- Proxy use was permitted only when a director had an "accident" (事故 - jiko), implying an unforeseen impediment or unavoidable circumstance preventing personal attendance, not mere convenience.

- The range of eligible proxies was narrowly restricted to the director's spouse or a first-degree relative (e.g., parent, child).

- The proxy's attendance was predicated on the director's own selection or designation.

- Considering these significant limitations, the Supreme Court concluded that this specific bylaw provision could not be said to harm or undermine the fundamental relationship of trust between the management association (Y) and its directors.

Outcome of the Appeal:

The Supreme Court found the High Court's decision to uphold the bylaw and dismiss X's claim to be correct. It stated that X's arguments were based either on a unique interpretation of the law or on criticisms of the High Court's wording that did not amount to a reversible error. X's appeal was therefore dismissed.

Analysis and Broader Implications

The Supreme Court's 1990 ruling provided important clarity on a practical issue facing many condominium management associations, especially those with geographically dispersed membership.

1. Reconciling Director's Personal Duty with Practical Governance:

The core tension in this case was between the principle that a director's duties are personal and based on trust, and the practical need for effective governance when personal attendance at every meeting is difficult. Former Civil Code Article 55 reflected the concern about overly broad delegation diluting a director's personal responsibility. The Supreme Court, while acknowledging this principle, found that it did not create an absolute bar to any form of proxy use in internal board deliberations, provided such use was carefully circumscribed.

2. The "Essential Nature of the Mandate" and Trust Relationship:

The judgment's emphasis on not contravening the "essential nature of the mandate" (委任の本旨 - inin no honshi) or harming the "relationship of trust" (信任関係 - shinnin kankei) is key. The Court's substantive assessment of the bylaw focused on whether these core principles were violated.

- Protecting the Association's Interests:

- Necessity for Proxy: The "accident" (jiko) requirement ensures that proxies are used out of necessity, preventing directors from routinely delegating their responsibilities simply to avoid attending. This safeguards against director absenteeism undermining the board's function.

- Appropriateness of Proxy:

- Proxy Competence: While directors of business corporations are often chosen for specific expertise, directors of condominium associations are typically unit owners, often serving voluntarily without specialized professional skills. The trust placed in them may stem more from their shared interest as co-owners. Therefore, expecting a proxy to have identical "competence" to the director might be misplaced.

- Proxy Governance & Alignment of Interests: The limitation of proxies to spouses or first-degree relatives was seen as a crucial safeguard. Such individuals are likely to share a common household or close financial and personal ties with the director (who is also a unit owner). This inherently aligns their interests more closely with those of the director and, by extension, the association, compared to an unrelated third party. It also implies a degree of oversight and trust between the director and their chosen proxy. This addressed concerns about a proxy acting against the association's interests or the director abdicating responsibility.

- Limited Scope of Delegation: The delegation was for participation in a specific board meeting, not a general handover of all directorial duties.

- Respecting Organizational Autonomy:

The decision respects the right of a condominium association, as an autonomous organization, to define its own internal operating rules through its bylaws, especially where the Condominium Ownership Act grants such flexibility. The Supreme Court acknowledged that associations should have the freedom to adopt rules that meet their specific circumstances (like having many non-resident directors in a resort condominium).

3. Practical Implications for Condominium Bylaws:

This ruling provided a green light for condominium associations to include carefully drafted provisions in their bylaws allowing for limited proxy participation in board meetings. The key elements for such provisions, drawing from the Court's reasoning, would include:

- A clear definition of the circumstances under which a proxy can be used (e.g., unavoidable absence).

- Strict limitations on who can act as a proxy (e.g., close family members or perhaps other unit owners, depending on what the association deems appropriate to maintain the trust relationship).

- Clarity on the scope of the proxy's authority (e.g., attendance and voting rights for that specific meeting).

4. Evolution of Governance Norms:

While this judgment addressed a specific bylaw under the legal framework of its time, the principles it espoused – balancing a director's personal responsibility with practical governance needs and organizational autonomy – remain relevant. Modern condominium management continues to evolve, and best practices often encourage direct participation. However, for associations with unique challenges like dispersed membership, well-crafted proxy rules, consistent with the spirit of this judgment, can be a valuable tool for maintaining operational continuity.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's November 1990 decision was a significant affirmation of the ability of Japanese condominium management associations to adopt practical governance rules tailored to their specific needs, provided these rules do not fundamentally violate the trust inherent in a director's position. By upholding a bylaw that allowed limited proxy attendance and voting at board meetings by close relatives in cases of a director's unavoidable absence, the Court recognized that strict adherence to the principle of a director's purely personal performance of duties could be tempered by reasonable, carefully defined exceptions. This ruling provided crucial flexibility, particularly for associations like resort condominiums, enabling them to function more effectively while still safeguarding the core principles of directorial responsibility and the trust placed in them by the unit owners.