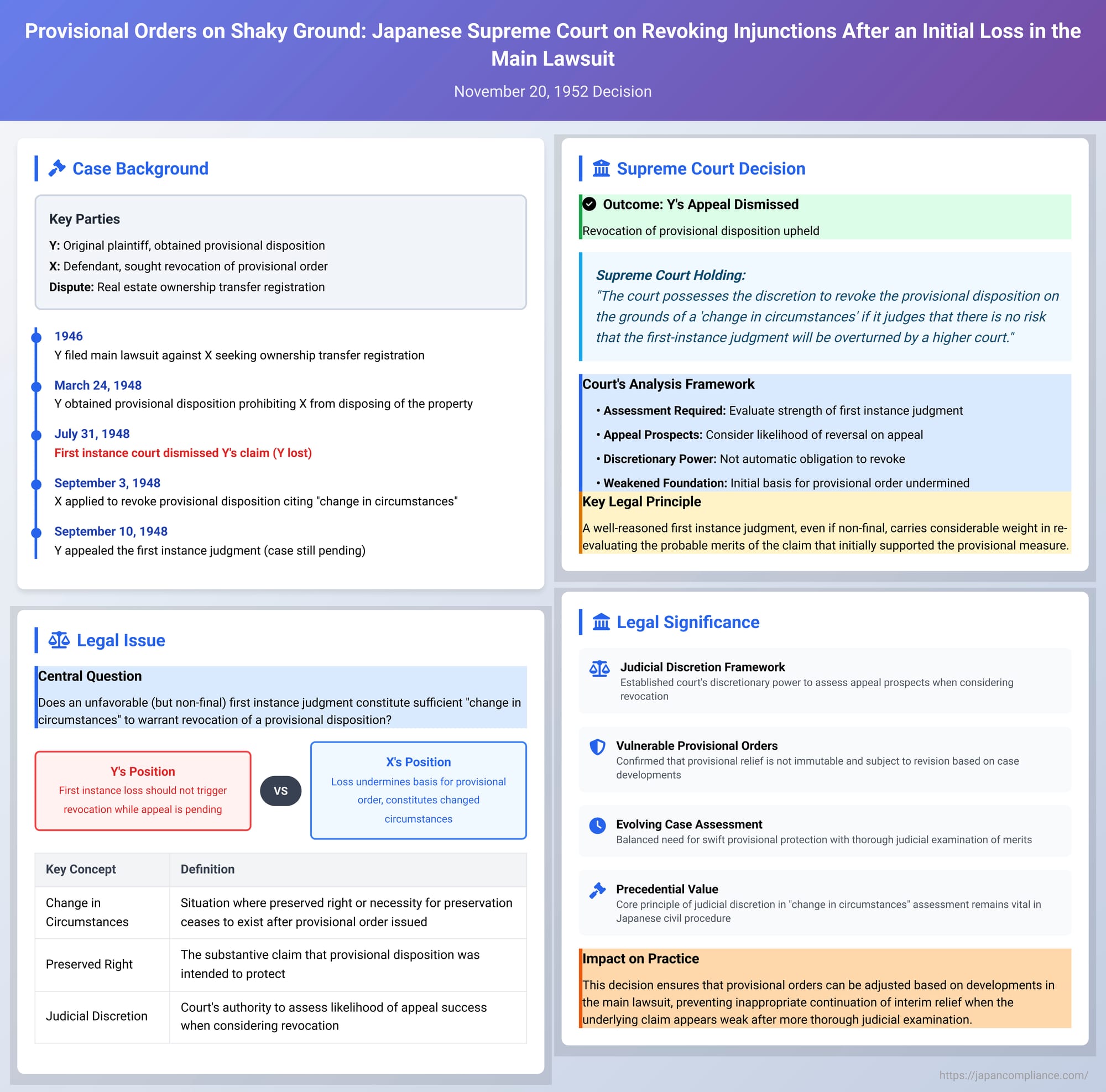

Provisional Orders on Shaky Ground: Japanese Supreme Court on Revoking Injunctions After an Initial Loss in the Main Lawsuit

Date of Supreme Court Decision: November 20, 1952

Provisional dispositions (保全命令 - hozen meirei) in Japanese civil procedure, such as an injunction prohibiting the disposal of property, are granted to secure a claimant's alleged rights pending the final outcome of a main lawsuit. These interim measures are based on a preliminary showing of a "preserved right" (被保全権利 - hihozen kenri) and the "necessity of preservation" (保全の必要性 - hozen no hitsuyōsei). However, given their issuance often occurs based on limited evidence and sometimes without a full hearing of the opposing party, a crucial question arises: what happens to the provisional disposition if the party who obtained it subsequently faces a setback in their main case? A 1952 Supreme Court of Japan decision (Showa 24 (O) No. 122) addressed this, specifically concerning whether such a provisional order should be revoked due to a "change in circumstances" (事情の変更 - jijō no henkō) when the initial applicant loses the main lawsuit at the first instance, even if that judgment is still under appeal.

The Factual History: A Property Dispute and an Interim Ban

The case involved a dispute over real estate between Y (the original plaintiff in the main lawsuit who obtained the provisional disposition) and X (the defendant in the main lawsuit who later sought the revocation of the provisional disposition).

- Main Lawsuit and Provisional Disposition: In 1946, Y initiated a lawsuit against X, seeking the registration of an ownership transfer for certain real property. While this main lawsuit was ongoing, on March 24, 1948, Y applied for and was granted a provisional disposition. This order prohibited X from disposing of the real estate in question until the judgment in the main lawsuit became final and binding.

- Reversal of Fortune in the Main Lawsuit: On July 31, 1948, the court of first instance in the main lawsuit delivered its judgment, ruling against Y and dismissing Y's claim for ownership transfer registration.

- Application to Revoke Provisional Disposition: Following this unfavorable outcome for Y in the main lawsuit's first instance, X, on September 3, 1948, applied to the court to revoke the provisional disposition. X argued that Y's loss in the main case constituted a "change in circumstances" that undermined the basis for the provisional order. This application by X is the subject of the present Supreme Court decision.

- Appeal in Main Lawsuit: It is important to note that Y immediately appealed the first-instance judgment in the main lawsuit on September 10, 1948. Consequently, at the time the oral arguments for X's application to revoke the provisional disposition were concluded, the first-instance judgment dismissing Y's main claim was not yet final and binding, as it was under appellate review.

Lower Court Rulings in the Revocation Proceedings:

The court of first instance handling X's application granted the request and ordered the revocation of the provisional disposition. Y appealed this decision. The High Court also dismissed Y's appeal, upholding the revocation. The High Court reasoned that when a creditor (Y) who obtained a provisional disposition is subsequently defeated in the main lawsuit at first instance, it creates a strong inference that the facts justifying the provisional disposition may not exist. Unless there are special circumstances suggesting that the first-instance judgment is highly likely to be overturned on appeal (and Y had not demonstrated such circumstances), the provisional disposition should be revoked due to this change in circumstances. Y then appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Dilemma: Does an Unfavorable (but Non-Final) Judgment Constitute a "Change in Circumstances"?

The core legal issue was whether a first-instance judgment against the party who obtained a provisional disposition, even if that judgment is still under appeal and thus not final, constitutes a sufficient "change in circumstances" to warrant the revocation of the provisional disposition. The lower courts had effectively said yes, subject to an assessment of the appeal's likely success.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Judicial Discretion Based on Likelihood of Appeal Success

The Supreme Court, in its decision of November 20, 1952, dismissed Y's appeal, thereby affirming the revocation of the provisional disposition.

Core Holding: The Court ruled that in a situation where a provisional disposition has been granted, and the party who applied for it (the creditor) subsequently loses their main lawsuit at the first instance:

- The court considering an application to revoke the provisional disposition is not automatically obligated to revoke it, nor does the unfavorable first-instance judgment automatically confer the right to have it revoked.

- However, the court possesses the discretion (自由裁量 - jiyū sairyō) to revoke the provisional disposition on the grounds of a "change in circumstances" if it judges that there is no risk (おそれがない - osore ga nai), or no significant likelihood, that the first-instance judgment (which was unfavorable to the provisional disposition holder) will be overturned by a higher court.

Interpretation of the Ruling:

This ruling means that the court tasked with deciding on the revocation must perform an assessment. It needs to evaluate the apparent strength of the first-instance judgment in the main lawsuit and the prospects of the pending appeal. If the first-instance judgment appears well-reasoned and unlikely to be reversed, then the original basis for the provisional disposition (which typically presumes the claimant has a probable claim) is significantly weakened. This weakening or discrediting of the initial grounds for the provisional order can constitute a "change in circumstances" justifying its revocation.

Understanding "Change in Circumstances" (事情の変更 - jijō no henkō)

The concept of "change in circumstances" is a key mechanism for adjusting or terminating provisional remedies that are, by their nature, interim and based on preliminary assessments. Article 38 of the current Civil Provisional Remedies Act (CPRA) (and similar provisions in the old Code of Civil Procedure under which this case was decided) allows for the revocation of a provisional order on this ground.

- General Definition: A "change in circumstances" typically refers to a situation where either the "preserved right" or the "necessity of preservation"—the two fundamental requirements for issuing a provisional order—ceases to exist after the order has been granted.

- Examples of Post-Order Changes: This could include the preserved right being extinguished through payment, settlement, waiver, or set-off, or the necessity for preservation disappearing due to a significant improvement in the debtor's financial situation. For instance, if a company director's duties were suspended by a provisional order, and that director was subsequently lawfully dismissed by a valid shareholders' resolution, this would constitute a change in circumstances.

- Initial Lack of Grounds as a "Change in Circumstances": Crucially, legal interpretation and practice have expanded this concept. It is also considered a "change in circumstances" if it is later discovered or adequately demonstrated that the grounds for the provisional order (the preserved right or the necessity for preservation) were actually lacking from the very beginning, but the debtor was only able to learn of or prove this fact after the order was issued. This stems from the understanding that provisional orders are often granted urgently based on prima facie proof (somei), a lower standard than full proof, and their validity is always subject to review through more thorough subsequent proceedings (like an objection or the main lawsuit itself). The provisional nature of the order means that a later, more considered judgment on the facts or law should take precedence.

- Relationship with "Preservation Objection" (保全異議 - hozen igi): An initial lack of grounds for the provisional order is also a primary reason for filing a "preservation objection" under CPRA Article 26 (a procedure for the debtor to challenge the provisional order before the court that issued it). While the CPRA attempts to delineate different review procedures, legal commentary suggests that in practice, grounds that could justify revocation due to a change in circumstances can often also be raised as part of a preservation objection, especially if those "changed" circumstances reveal an initial flaw in granting the order.

The Main Lawsuit's Outcome as a Key "Change in Circumstance"

The outcome of the main lawsuit, to which the provisional disposition is ancillary, is a particularly significant factor:

- Final Judgment Against the Provisional Creditor: If the main lawsuit definitively concludes with a final judgment against the creditor who obtained the provisional order, determining that their "preserved right" does not exist, this unequivocally constitutes a "change in circumstances." The provisional order can then be revoked upon application. (While some older theories suggested an automatic lapse of the provisional order in such cases, the established view under both old and current law is that a formal application for revocation is generally necessary).

- Non-Final First-Instance Judgment Against the Provisional Creditor (as in this 1952 case): This Supreme Court decision confirms a line of precedents from the pre-war Grand Court of Judicature (大審院 - Daishin'in). It establishes that even a non-final first-instance judgment dismissing the provisional creditor's claim in the main lawsuit can be treated as a "change in circumstances." The revoking court has the discretion to cancel the provisional order if it assesses that the first-instance judgment is sound and unlikely to be overturned on appeal. This signifies that a full judicial examination at first instance, even if subject to appeal, carries considerable weight in re-evaluating the probable merits of the claim that initially supported the provisional measure.

Related Considerations (from Legal Commentary)

Legal commentary on this and related topics sheds further light:

- Maintaining Provisional Orders for Different Claims: If a provisional order is sought to be revoked because the specific "preserved right" cited for it has been found non-existent (e.g., by a first-instance judgment in the main case), the creditor generally cannot argue for keeping that same provisional order in place to protect a different (even if related) claim, especially if that different claim could have been, or is being, litigated separately. This would be an improper "repurposing" of the original provisional order and could circumvent the proper procedures for obtaining provisional relief for the new claim.

- "No Surplus" Scenario and Change in Circumstances: A separate but related issue often discussed under "change in circumstances" involves a creditor who obtains a provisional attachment, then wins a final judgment in the main suit, and initiates compulsory execution on the provisionally attached property. If that compulsory execution is then cancelled because of "no surplus" (i.e., the expected sale proceeds won't cover prior liens and auction costs), can the debtor then successfully apply to revoke the original provisional attachment due to a change in circumstances?

- Views on this have varied. Some argue that if there's a future possibility of a surplus (e.g., property values rise), the provisional attachment should remain to secure that possibility.

- Others contend that once a final judgment is obtained and the creditor has the means for full execution, the "necessity of preservation" that justified the provisional measure may have fundamentally changed or ceased, especially if the attempted full execution fails for reasons like "no surplus."

- Later Supreme Court cases (e.g., from Heisei 10 (1998) and Heisei 14 (2002)) have clarified that a provisional attachment's securing effect can co-exist with a subsequent (main) execution against the same property (the "coexistence theory" - 併存説 - heizonsetsu), for instance, preserving the creditor's priority gained by the provisional attachment. This complicates the "change of circumstances" argument in "no surplus" main execution scenarios.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1952 decision in this case established an important principle regarding the vulnerability of provisional dispositions when the underlying main lawsuit takes an unfavorable turn for the party who obtained the interim relief. By granting courts the discretion to revoke a provisional disposition based on a first-instance loss in the main case (if that loss is deemed unlikely to be reversed on appeal), the ruling acknowledges that the foundation for provisional relief can be significantly eroded even before a final, unappealable judgment is rendered.

This balances the need to provide swift, provisional protection with the evolving understanding of the merits of the case as it progresses through more thorough judicial examination. It underscores that provisional orders are not immutable and are always subject to revision or revocation if the circumstances that justified their issuance demonstrably change or are proven to have been misconceived from the start. While the legal framework for provisional remedies has evolved since 1952 with the enactment of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act, the core principle of judicial discretion in assessing a "change in circumstances" based on developments in the main lawsuit remains a vital aspect of Japanese civil procedure.