Proving Causation in Medical Malpractice: Japan's Supreme Court and the "High Degree of Probability" Standard

Date of Judgment: October 24, 1975 (Showa 50)

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, 1973 (O) No. 517

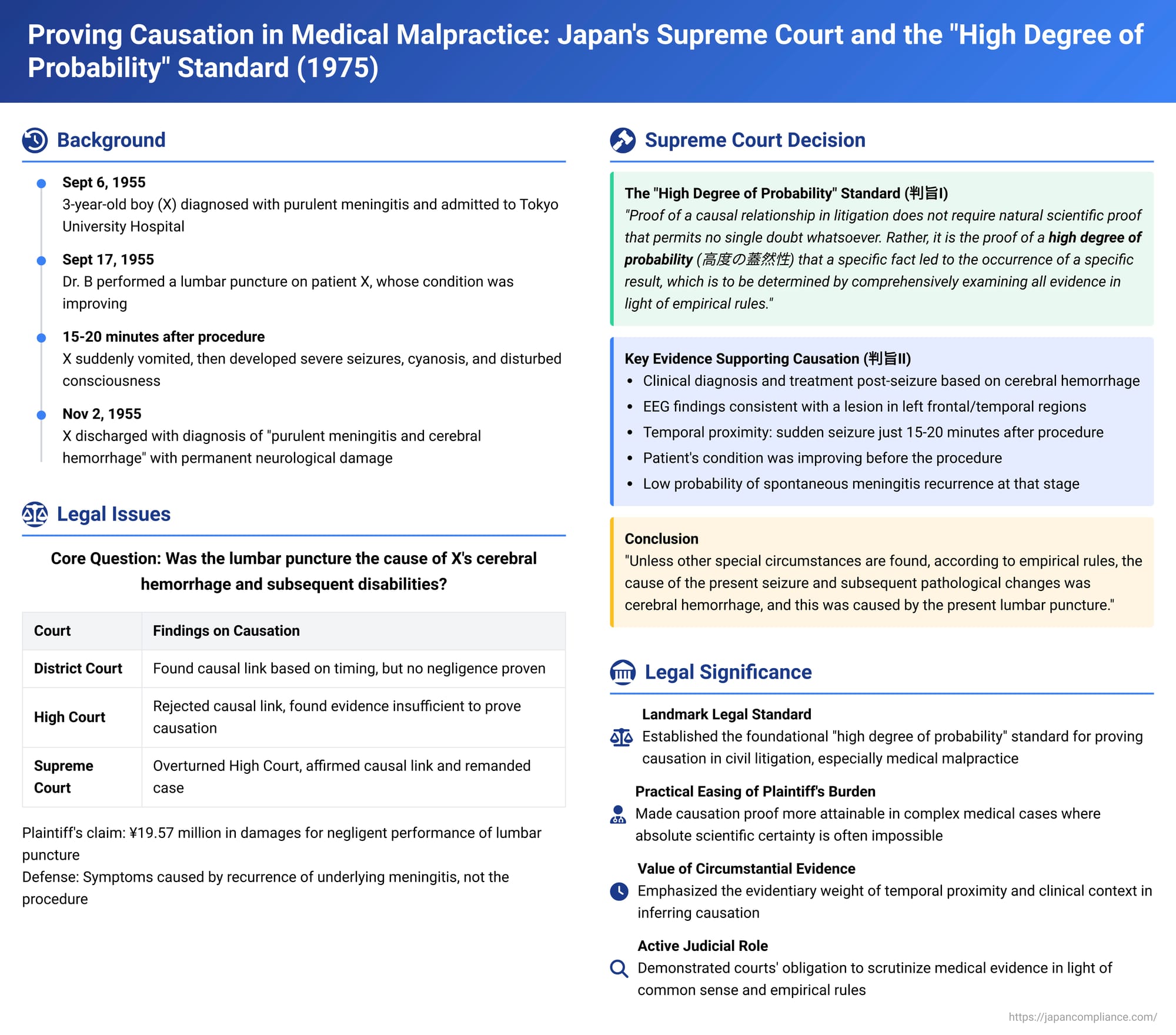

In a seminal judgment delivered on October 24, 1975, the Supreme Court of Japan provided a foundational articulation of the standard of proof required to establish a causal link in medical malpractice litigation. This case, arising from severe neurological damage suffered by a young child following a lumbar puncture, is renowned for its clear statement that legal proof of causation does not demand absolute scientific certainty but rather a "high degree of probability" based on a comprehensive assessment of all evidence through the lens of empirical rules. This ruling has had a lasting and widespread influence on civil litigation, particularly in the complex realm of medical injury claims.

Factual Background: A Child's Treatment for Meningitis Takes a Tragic Turn

The case involved X, a three-year-old boy, who was diagnosed with purulent meningitis (a severe bacterial infection of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord) on September 6, 1955 (Showa 30). He was admitted to the pediatric department of Tokyo University Hospital, which was operated by Y, the State of Japan. X came under the care of attending physician Dr. A and Dr. B, who administered treatment that included daily lumbar punctures (also known as spinal taps). This procedure involved inserting a needle into the lumbar spine to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for analysis and to inject medications like penicillin directly into the spinal canal.

Initially, X's condition was extremely serious. However, the treatment, including the lumbar punctures, appeared to be effective, and his condition gradually improved. Reflecting this progress, from September 15, the frequency of the lumbar punctures was reduced to every other day.

On September 17, 1955, Dr. B performed what would become a critical lumbar puncture on X (referred to as "the present lumbar puncture"). Approximately 15 to 20 minutes after this procedure was completed, X suddenly and violently vomited. His condition subsequently deteriorated rapidly. About two hours after the initial vomiting, he began to exhibit severe neurological symptoms, including convulsions affecting his face and entire body, cyanosis (bluish discoloration of the lips due to lack of oxygen), and a disturbed level of consciousness. This cluster of acute symptoms was collectively termed "the present seizure."

Following this dramatic turn, Drs. A and B initiated treatment for both a suspected cerebral hemorrhage (bleeding in the brain) and the ongoing purulent meningitis. X was eventually discharged from the hospital on November 2, 1955, with a final diagnosis of "purulent meningitis and cerebral hemorrhage." He was left with significant permanent neurological impairments, including right-sided hemiparesis (partial paralysis). Ultimately, X suffered from lasting intellectual and motor disabilities ("the present sequelae").

The Legal Claim and Defense: Allegations of Negligence and Contested Causation

X, through his representatives, sued Y (the State) for damages amounting to approximately 19.57 million yen. The claim was based on tort, alleging negligence on the part of the hospital's physicians, Drs. A and B, for which the State was vicariously liable. The core allegations of negligence were:

- Dr. B performed "the present lumbar puncture" in a negligent manner. It was claimed that X was struggling and had to be forcibly restrained during the procedure, and this, combined with the puncture technique, might have caused sudden, sharp changes in intracranial pressure, leading to a cerebral hemorrhage.

- Dr. A, as the chief attending physician, provided insufficient supervision and guidance regarding X's nursing care and overall treatment.

The plaintiffs asserted that this negligence during the lumbar puncture directly caused a cerebral hemorrhage in X, which in turn led to "the present seizure" and "the present sequelae."

The State (Y) contested these claims, arguing primarily that "the present seizure" and the subsequent permanent disabilities were not caused by the lumbar puncture or any alleged negligence, but rather by a recurrence or exacerbation of the underlying purulent meningitis.

Lower Court Proceedings: A Divergence on the Causal Link

The case progressed through the lower courts with differing findings, particularly on the critical issue of causation:

- First Instance Court:

- The trial court, after considering the progression of symptoms and the course of treatment, found that X's condition following "the present seizure" was indeed attributable to a cerebral hemorrhage.

- Regarding the causal link between "the present lumbar puncture" and this cerebral hemorrhage, the court adopted a form of presumptive reasoning. It noted the close temporal proximity: the vomiting and subsequent severe symptoms began shortly after the lumbar puncture. In the absence of other specific, identifiable causes for such a sudden deterioration, the court found it reasonable to presume that "the present lumbar puncture" had caused "the present seizure" and the cerebral hemorrhage.

- Despite this finding on causation, the first instance court ultimately dismissed X's claim because it did not find that the physicians had been negligent in the performance of the lumbar puncture or in their overall management.

- High Court:

- On appeal, the High Court also found no negligence on the part of the physicians.

- Critically, however, the High Court diverged from the trial court on the issue of causation. While acknowledging that there was a suspicion that "the present seizure" and the subsequent cerebral hemorrhage (or a worsening of the meningitis) might have been caused by "the present lumbar puncture," the High Court, based on its interpretation of various expert medical opinions presented, concluded that a causal link had not been sufficiently established.

- Consequently, the High Court upheld the dismissal of X's claim. X then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (October 24, 1975)

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings. This decision is most famous for its clear articulation of the standard of proof for causation in civil litigation.

1. The Standard of Proof for Causation in Litigation (判旨Ⅰ - Hanshi I):

The Court laid down the following general principle, which has since become a cornerstone of Japanese civil procedure, especially in medical malpractice cases:

"Proof of a causal relationship in litigation does not require natural scientific proof that permits no single doubt whatsoever. Rather, it is the proof of a high degree of probability (高度の蓋然性 - kōdo no gaizensei) that a specific fact led to the occurrence of a specific result, which is to be determined by comprehensively examining all evidence in light of empirical rules (経験則 - keikensoku). The determination thereof requires that an ordinary person could hold a conviction of its truthfulness to a degree that leaves no room for doubt, and this is sufficient."

This statement clarified that the legal standard for proving causation is not the same as the rigorous, often absolute, certainty sought in the natural sciences. Instead, it is a standard based on strong likelihood and common-sense reasoning applied to the available evidence.

2. Re-evaluation of Evidence and Application to the Facts (判旨Ⅱ - Hanshi II):

The Supreme Court then meticulously re-examined the factual evidence, concluding that the High Court had erred in its assessment of causation. The Supreme Court highlighted several key pieces of evidence and reasoning that supported a finding of a causal link between "the present lumbar puncture" and X's cerebral hemorrhage:

- (a) Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment Post-Seizure: Medical records and witness testimony (including that of Dr. A, the attending physician) indicated that following "the present seizure," X was diagnosed and treated on the premise that a cerebral hemorrhage had occurred. This treatment approach for cerebral hemorrhage continued at least until X's discharge. Furthermore, one expert witness (Expert K) opined that given X's clinical symptoms—the sudden onset of convulsions with disturbed consciousness, followed by aphasia and right hemiparesis—cerebral hemorrhage was the most probable cause of "the present seizure."

- (b) Electroencephalogram (EEG) Findings: An EEG specialist (Expert H), while cautious about making a definitive etiological diagnosis from EEG alone, reported that X's EEG recordings showed findings indicative of brain dysfunction and a lesion primarily localized in the left frontal and temporal regions of the brain. This localization was consistent with the clinical manifestation of right-sided hemiparesis.

- (c) Temporal Proximity and Clinical Context: The Supreme Court placed significant emphasis on the following:

- X's underlying condition (purulent meningitis) had been showing consistent improvement leading up to September 17.

- "The present seizure" occurred suddenly and dramatically, just 15 to 20 minutes after "the present lumbar puncture" was performed.

- The probability of a spontaneous recurrence of purulent meningitis of such severity at that stage was generally considered low, and there were no specific circumstances presented that would suggest a high likelihood of such a recurrence.

- (d) Conclusion on Causation: Based on a comprehensive review of these facts, and applying its "high degree of probability" standard, the Supreme Court concluded: "Unless other special circumstances are found, according to empirical rules, the cause of the present seizure and subsequent pathological changes was cerebral hemorrhage, and this was caused by the present lumbar puncture. Ultimately, it is appropriate to affirm a causal relationship between X's present seizure and subsequent pathological changes, and the present lumbar puncture."

The Supreme Court found that the expert opinions and witness testimonies, when carefully examined, did not preclude this conclusion, contrary to the High Court's interpretation. It therefore held that the High Court had erred in its application of the rules concerning causation and had failed to properly assess the evidence. Since the issue of physician negligence had not been definitively ruled upon by the High Court in a manner consistent with a finding of causation, the case was remanded for a new trial to address negligence and other remaining issues. (A supplementary opinion by Justice Kichio Otsuka provided a more detailed rebuttal of the High Court's interpretation of the expert testimonies, arguing that they did, in fact, support the possibility of the lumbar puncture causing the hemorrhage).

Analysis and Implications: Reshaping the Landscape of Medical Causation Proof

The Supreme Court's 1975 decision in the "Lumbar Puncture Case" is a landmark for several critical reasons:

- Establishing the "High Degree of Probability" Standard: This ruling is most renowned for clearly articulating that the standard of proof for causation in civil litigation (including medical malpractice) is not absolute scientific certainty but a "high degree of probability." This pragmatic standard acknowledges the inherent complexities and uncertainties often involved in medical science.

- Implicit Easing of the Plaintiff's Burden: While the Court did not formally declare a "lowering" of the burden of proof (and legal scholars debate the precise impact on formal evidence law), the practical effect of the "high degree of probability" standard, coupled with the emphasis on "empirical rules" and the "ordinary person's conviction," was widely interpreted as providing a more attainable pathway for plaintiffs to prove causation in difficult medical cases. It signaled that courts should not impose an impossibly high evidentiary bar where direct, irrefutable scientific proof of a specific causal chain is often unavailable.

- Significance of Temporal Proximity and Circumstantial Evidence: The Court's strong reliance on the close timing between the medical intervention (lumbar puncture) and the adverse event (seizure), particularly in the context of the patient's prior improvement and the low likelihood of alternative causes, underscored the significant weight that can be given to circumstantial evidence and temporal relationships in inferring causation.

- Active Judicial Scrutiny of Evidence, Including Expert Opinions: The Supreme Court's willingness to engage in a detailed re-evaluation of the factual evidence and the interpretation of expert testimonies, rather than deferring entirely to the lower court's assessment, demonstrated a more active judicial role in ensuring that evidence is weighed in a manner consistent with common sense and empirical rules.

- Profound Impact on Medical Malpractice Litigation: This judgment became a cornerstone precedent, frequently cited in subsequent medical malpractice lawsuits in Japan. It is widely seen as a pivotal development that helped to level the playing field for patients alleging medical negligence, by providing a clearer and arguably more achievable standard for demonstrating the causal link between a medical act or omission and the harm suffered.

- Balancing Justice with Scientific Uncertainty: The ruling reflects a judicial effort to balance the pursuit of justice for injured individuals with a realistic understanding of the limits of scientific knowledge. It acknowledges that while medical evidence is crucial, legal decision-making must sometimes proceed based on strong probabilities rather than absolute certainties to avoid denying redress to deserving plaintiffs.

The PDF commentary accompanying this case notes that this ruling, while maintaining the traditional framework of judicial conviction, was seen by many as practically easing the plaintiff's burden. It also points to the potential for tension between judicial findings of causation based on "empirical rules" and the perspectives of the medical community, which may demand more rigorous scientific validation. This highlights the ongoing dialogue between law and medicine in the context of medical accidents.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1975 decision in the Lumbar Puncture Cerebral Hemorrhage Causation Case remains a foundational pillar of Japanese medical malpractice jurisprudence. By establishing the "high degree of probability" as the standard for proving causation and by emphasizing a comprehensive, common-sense evaluation of all evidence, the Court provided a crucial legal tool for navigating the inherent complexities of medical injury claims. This ruling has significantly influenced the conduct of medical litigation in Japan for decades, striving to ensure that the pursuit of justice is not stymied by an overly rigid demand for scientific certainty in contexts where such certainty is often unattainable. It continues to guide courts in their difficult task of adjudicating responsibility when medical interventions are followed by adverse outcomes.