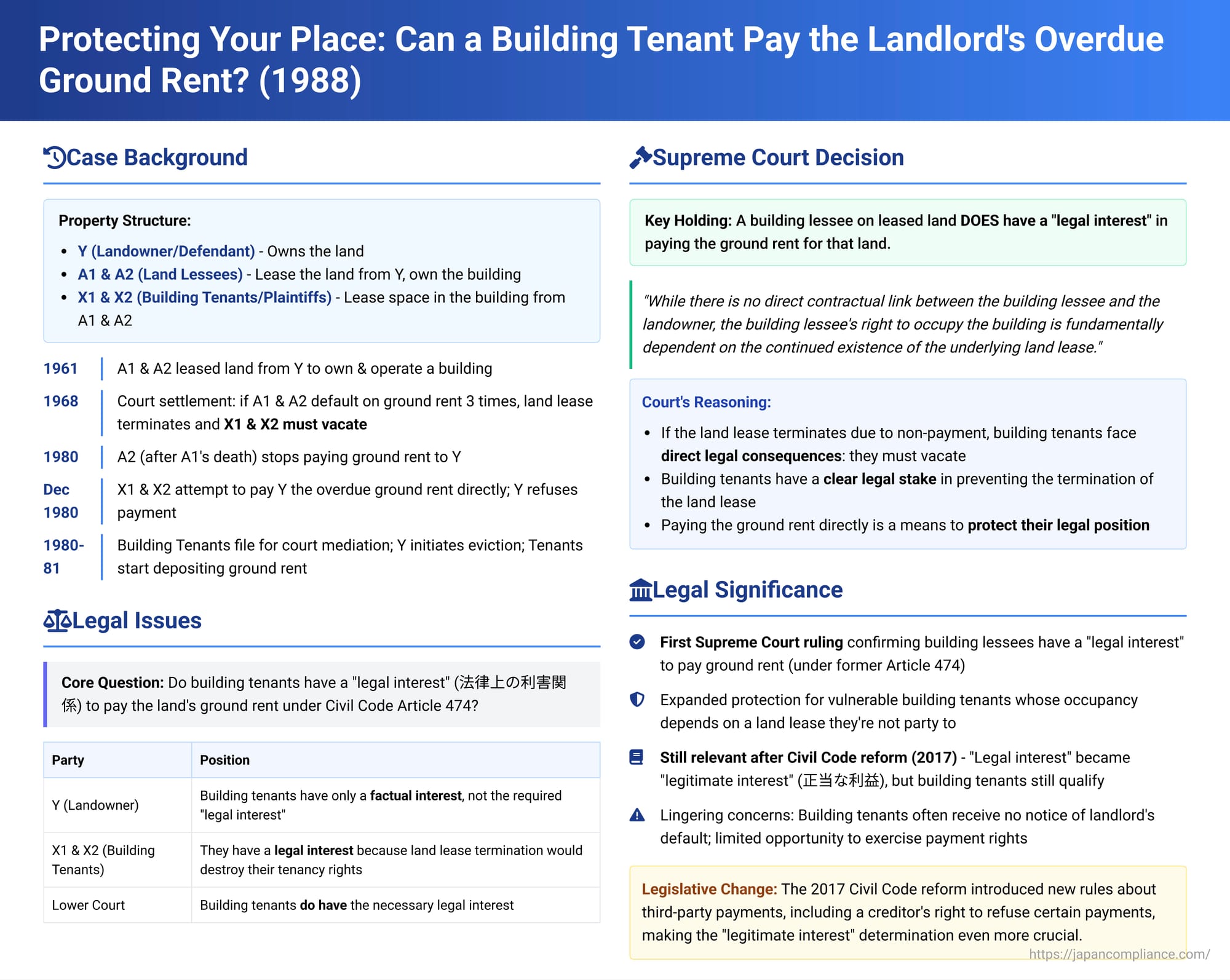

Protecting Your Place: Can a Building Tenant Pay the Landlord's Overdue Ground Rent in Japan?

Imagine you're a tenant happily running your business or living in a building. Unbeknownst to you, your landlord (who owns the building but leases the land it stands on) stops paying the ground rent to the landowner. If the landowner terminates the land lease due to this default, your right to occupy the building could vanish, leading to eviction. Can you, as a mere building tenant, step in and pay your landlord's overdue ground rent to save your own tenancy? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this critical question in a judgment on July 1, 1988 (Showa 62 (O) No. 1577), clarifying the rights of building tenants in such precarious situations.

Third-Party Payment of Debts in Japan (Under Former Civil Code Article 474)

At the time of this judgment, Japanese Civil Code Article 474 governed the payment of a debt by a third party (someone other than the actual debtor). The general rule was that a third party could pay someone else's debt. However, there was a key exception:

- If a third party lacked a "legal interest" (hōritsu-jō no rigai kankei) in making the payment, their payment was invalid if it was made against the debtor's will.

The definition of "legal interest" was therefore crucial. It was generally understood to include parties like guarantors or owners of property pledged as security, whose own legal positions would be directly affected if the debt wasn't paid. A mere factual or emotional interest (like that of a relative) was not enough.

Facts of the 1988 Case: Tenants Facing Eviction Try to Pay Landlord's Ground Rent

The case involved a complex multi-party property dispute:

- The Parties:

- Y: The landowner (the defendant/appellant).

- A1 and A2: Husband and wife who jointly leased the land from Y in 1961 to own and operate a building on it (the "Land Lessees"). A1 later passed away, and A2 inherited his obligations.

- X1 and X2: Tenants who leased the first floor of the building from A1 (the "Building Tenants," plaintiffs/appellees). A1 and A2 occupied the second floor.

- The Looming Threat: A1 and A2 defaulted on their ground rent payments to Y. This led to a court action by Y, which resulted in a 1968 court settlement. This settlement stipulated that if A1 and A2 defaulted on ground rent three more times, the land lease would automatically terminate, they would have to remove the building and vacate the land, and importantly, the Building Tenants (X1 and X2) would also have to vacate the building.

- Renewed Default and Tenants' Dilemma: Years later, in 1980, A2 (now solely responsible after A1's death and facing financial difficulties) again stopped paying the ground rent to Y. When one of the Building Tenants (X2) tried to pay their building rent to A2, A2 refused it and mentioned being behind on the ground rent payments. The Building Tenants, fearing that A2's default would trigger the 1968 settlement terms and lead to their eviction, grew concerned.

- Tenants' Attempt to Pay Ground Rent: On December 6, 1980, the Building Tenants offered to pay the overdue ground rent directly to Y's office on A2's behalf. However, Y (the landowner) refused to accept their payment.

- Legal Actions:

- The Building Tenants filed for court mediation, asking that A2 be ordered to pay the ground rent to Y, or failing that, that Y be compelled to accept payment from them (the Building Tenants) on A2's behalf.

- Before the mediation could proceed, Y initiated enforcement of the 1968 settlement terms to evict the Building Tenants.

- In response, the Building Tenants started depositing the overdue ground rent (for A2's account, for Y's benefit) and continued to deposit monthly ground rent amounts. They then filed a lawsuit to prevent Y from enforcing the eviction.

- A2, participating in Y's side of the lawsuit, claimed extreme financial hardship made it impossible to continue the land lease and that the Building Tenants had refused her earlier offers for a buyout or relocation fee. The Building Tenants, conversely, alleged that A2 and Y were colluding to force them out by orchestrating the default.

The lower appellate court had ruled in favor of the Building Tenants, finding that they did have a legal interest in paying the ground rent because the termination of the land lease would destroy the foundation of their own building tenancy. Y appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that any interest the Building Tenants had was merely factual and indirect, not the "direct legal interest" required by Article 474.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Building Lessees Have a "Legal Interest"

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal and upheld the appellate court's finding that the Building Tenants indeed possessed the necessary legal interest.

Core Finding: The Court ruled that a lessee of a building situated on leased land does have a legal interest in the payment of the ground rent for that land.

Reasoning: The Court's logic was straightforward:

- While there is no direct contractual link between the building lessee (X1, X2) and the landowner (Y), the building lessee's right to occupy the building is fundamentally dependent on the continued existence of the underlying land lease held by their landlord (A2).

- If the land lease is terminated (for example, due to non-payment of ground rent by the Land Lessee A2), the Building Tenants (X1, X2) would face a direct and unavoidable legal consequence: they would be legally obligated to vacate the building they lease and surrender the land to the landowner (Y).

- Therefore, the Building Tenants have a clear and substantial legal interest in preventing the termination of the land lease, and paying the overdue ground rent is a direct means to protect this interest.

The Court concluded that the appellate court's judgment recognizing this legal interest was correct.

Significance Under the Pre-2017 Civil Code

This 1988 judgment was the first Supreme Court ruling to definitively clarify that a building lessee on leased land had the requisite "legal interest" under former Article 474(2) to pay the ground rent on behalf of their landlord. It confirmed that the interest did not need to be as traditionally "direct" as that of a guarantor or a surety, but could arise from a clear legal vulnerability that would be triggered if the primary debt (the ground rent) went unpaid. This was a significant step in protecting such tenants.

Relevance and Changes Under the Reformed (Post-2017) Civil Code

The Japanese Civil Code underwent major reforms in 2017, including revisions to Article 474 concerning third-party payments.

- "Legal Interest" became "Legitimate Interest" (seitō na rieki): The terminology in Article 474 was changed. The concept of a third party needing an interest to pay against the debtor's will (or, under new rules, potentially against the creditor's will) now uses the phrase "legitimate interest." This change was partly to align the concept more closely with the requirements for statutory subrogation (the right of a paying third party to step into the creditor's shoes).

- The 1988 Judgment's Conclusion Still Stands: Legal commentators widely agree that the conclusion of the 1988 Supreme Court case remains valid under the reformed Civil Code. A building lessee in such a situation would still be considered to have a "legitimate interest" in paying the ground rent.

- New Protections and Rules in Reformed Article 474: The reformed Article 474 introduced new complexities and protections:

- Creditor Protection (Debtor's Objection): If a third party without a legitimate interest pays a debt against the debtor's will, the payment is still considered valid if the creditor did not know it was against the debtor's will (new Article 474(2) proviso). This protects the creditor from uncertainty.

- Creditor's Right to Refuse (New): A creditor can now generally refuse to accept payment from a third party who lacks a legitimate interest if the payment is against the creditor's own will (new Article 474(3) main part). This is particularly relevant if the creditor wishes to avoid a relationship with an undesirable third party (e.g., one involved in illicit activities) who might gain subrogation rights upon payment. An exception exists if the third party is paying under the debtor's instruction and the creditor is aware of this.

These changes make the determination of "legitimate interest" even more crucial, as it now also impacts the creditor's ability to refuse payment.

The Precarious Position of Building Lessees – Lingering Issues

This Supreme Court decision highlighted the vulnerability of building tenants on leased land. If their landlord defaults on ground rent, the landowner can indeed terminate the land lease, and this generally allows the landowner to evict the building tenants (as confirmed by other Supreme Court precedents, especially in cases of statutory termination for default, as here).

The commentary on the 1988 case points to lingering concerns for such building tenants:

- Opportunity for Third-Party Payment: Existing case law suggests that a landowner generally only needs to give notice of default (and demand for payment) to their direct tenant (the land lessee/building owner), not to the sub-tenants in the building. This means building tenants might not get a formal opportunity to pay the ground rent before termination proceedings are advanced. Many scholars argue that building tenants should be afforded such notice and an opportunity to pay to protect their occupancy.

- Agreements Prohibiting Third-Party Payment: What if the original land lease agreement contains a clause prohibiting third-party payment of the ground rent? While such clauses are generally considered valid, it's argued they should not be enforceable if designed to harm a third party (like a building tenant) who has a legitimate interest in making the payment.

Conclusion

The 1988 Supreme Court judgment was a vital affirmation of the rights of building tenants on leased land. By recognizing their "legal interest" (now "legitimate interest") in paying overdue ground rent to prevent the termination of the underlying land lease, the Court provided a crucial mechanism for these tenants to protect their homes and businesses from the consequences of their landlord's default. While the Civil Code's provisions on third-party payments have evolved, the core principle that such tenants are not mere bystanders but parties with a tangible stake in the survival of the land lease remains a key tenet of Japanese property and contract law.