Protecting Your Brand in Japan: Navigating IP Disputes and Reputational Harm

TL;DR

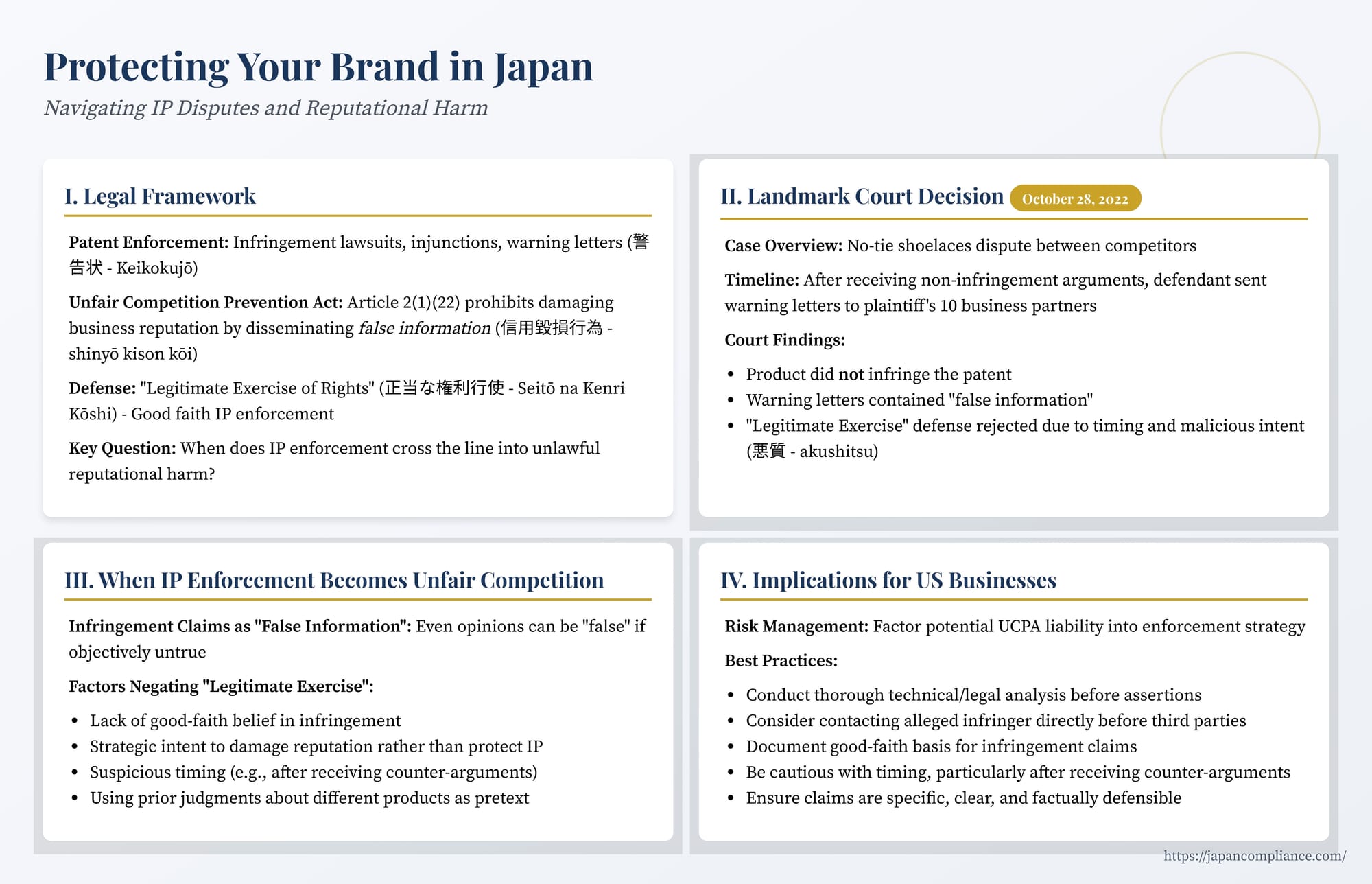

- Tokyo District Court (Oct 28 2022) ruled that patent-infringement warning letters sent to a rival’s customers were unfair competition under the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA).

- Because the product did not infringe and the sender ignored contrary evidence, the letters were “false information” and not a legitimate exercise of rights.

- Good-faith basis, timing, and purpose determine whether IP warnings are lawful in Japan.

- Rights holders must investigate thoroughly and avoid weaponising notices; recipients may counterclaim for reputational harm.

Table of Contents

- Legal Framework: IP Enforcement vs Unfair Competition in Japan

- The Case: Tokyo District Court, October 28 2022 (No-Tie Shoelaces Dispute)

- Key Legal Issues and Analysis

- Implications for US Businesses

- Conclusion

Aggressively enforcing intellectual property (IP) rights is often necessary to protect market share and brand value. However, overly zealous enforcement tactics, particularly in competitive markets like Japan, can backfire. Sending unsubstantiated or strategically timed infringement warnings can not only escalate disputes but also potentially expose the sender to liability for damaging a competitor's reputation under Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA).

Understanding the line between legitimate IP enforcement and unlawful competitive interference is crucial for businesses operating in Japan. A Tokyo District Court decision from October 28, 2022 (Reiwa 3 (Wa) No. 22940), illustrates this tension, finding that a company's patent infringement warnings constituted unfair competition aimed at harming a rival's business reputation.

Legal Framework: IP Enforcement vs. Unfair Competition in Japan

Navigating IP disputes in Japan requires understanding several key legal concepts:

- Patent Enforcement: The standard tools include filing infringement lawsuits seeking damages and/or injunctions against the infringing party.

- Warning Letters (警告状 - Keikokujō): It is common practice for rights holders to send warning letters directly to alleged infringers, and sometimes to their customers or distributors, demanding cessation of infringing activities. This is generally considered a permissible first step in enforcement.

- Unfair Competition Prevention Act (不正競争防止法 - Fusei Kyōsō Bōshi Hō): This act aims to ensure fair competitive practices. A key provision, Article 2(1)(22) (formerly 2(1)(xxi)), prohibits acts that damage the business reputation of a competitor by disseminating false information (信用毀損行為 - shinyō kison kōi).

- "False Information" (虚偽の事実 - Kyogi no Jijitsu): Critically, in the context of IP disputes, making incorrect claims of infringement can be treated as disseminating "false information" under the UCPA. Even statements framed as opinions (e.g., "Product X likely infringes Patent Y") may be deemed actionable factual assertions if they are objectively untrue and harm reputation.

- Defense: Legitimate Exercise of Rights (正当な権利行使 - Seitō na Kenri Kōshi): The UCPA generally does not penalize actions taken as a legitimate exercise of one's rights. Sending a warning letter based on a good-faith, reasonable belief that your valid IP rights are being infringed typically falls under this exception and is not considered illegal unfair competition. The key lies in the "good faith" and "reasonableness" of the assertion.

The critical question often becomes: when does an infringement warning cross the line from legitimate enforcement into unlawful reputational harm? The 2022 Tokyo District Court case provides valuable guidance.

The Case: Tokyo District Court, October 28, 2022 (No-Tie Shoelaces Dispute)

This case involved a complex history between two competitors in the market for "no-tie" shoelaces.

The Facts:

- Company X (Plaintiff) had been manufacturing and selling its "Caterpyrun" no-tie shoelaces since early 2013.

- Company Y1 (Defendant), which co-owned a relevant patent (Patent P) with Company X, initiated a lawsuit ("Prior Lawsuit") against X in June 2016, alleging infringement by the original Caterpyrun product. Around the same time, Y1 established a related company, Y2 (also a Defendant), and began selling competing shoelaces.

- In the Prior Lawsuit, the IP High Court issued an interim judgment (December 2018) finding that X's actions constituted infringement, specifically highlighting a breach related to the terms of the co-ownership agreement under Patent Act Article 73(2). (This nuance is important – the finding might have related more to contractual rights between the co-owners than the technical scope of the patent claims regarding the product itself).

- Following this interim ruling, Company X modified its product, launching "Caterpyrun+" around May 2019.

- The Prior Lawsuit eventually concluded, partially favoring Y1, and appeals were ultimately withdrawn.

- Settlement discussions between X and Y1 regarding various issues (including but not limited to Patent P) began in early 2021 but failed. Y1 had demanded that X exit the no-tie shoelace market entirely.

- In May 2021, Y1 sought a preliminary injunction against Company X, now claiming that the new product, Caterpyrun+, also infringed Patent P.

- Company X filed its initial arguments opposing the injunction on July 30, 2021, presumably detailing why Caterpyrun+ did not infringe Patent P.

- Less than three weeks later, on August 19, 2021, Company Y1 sent "Notice Letters" to ten of Company X's significant business partners (customers or distributors). These letters explicitly stated Y1's belief that Caterpyrun+ infringed Patent P.

- Company X responded by filing a new lawsuit against Y1 and Y2, alleging that sending these Notice Letters constituted the dissemination of false information detrimental to its business reputation under UCPA Article 2(1)(22) [then (xxi)] and seeking an injunction against further notices and damages.

Court's Finding on Infringement (Caterpyrun+):

Crucially, as a preliminary step in the UCPA lawsuit, the Tokyo District Court examined whether Caterpyrun+ actually infringed Patent P. The court concluded that it did not. This finding was fundamental to the subsequent unfair competition analysis.

Court's Finding on Unfair Competition:

- Dissemination of False Information: Since Caterpyrun+ was found not to infringe Patent P, the court held that Y1's Notice Letters, which claimed infringement, contained "false information." Sending these letters to X's business partners clearly had the potential to damage X's business reputation. Therefore, the act prima facie fell under UCPA Article 2(1)(22).

- Rejection of the "Legitimate Exercise of Rights" Defense: This was the core of the decision. Y1 argued its actions were merely enforcing its patent rights. The court disagreed, finding Y1's conduct went beyond legitimate enforcement. The key factors were:

- Timing and Knowledge: Y1 sent the Notice Letters after receiving Company X's detailed arguments in the injunction proceedings explaining why Caterpyrun+ did not infringe. The court found that Y1 knew, or could easily have recognized from X's submissions, that there was a substantial possibility the new product was non-infringing.

- Strategic Intent: The court inferred that Y1 strategically used the previous interim judgment (concerning the original Caterpyrun and potentially based on different legal grounds) as a pretext to target the new Caterpyrun+. The primary aim of the letters was seen not as good-faith enforcement against Caterpyrun+, but as an attempt to damage X's business relationships and stifle competition before the court could rule on the infringement status of the new product in the pending injunction case.

- Malice ("Akushitsu"): The court characterized Y1's conduct as "malicious" (悪質 - akushitsu). It concluded that Y1's actions were driven by a desire to gain an unfair competitive advantage by leveraging the prior dispute and damaging X's reputation, rather than by a genuine, good-faith effort to enforce its rights against the specific product in question (Caterpyrun+).

- Conclusion: Because Y1 acted with knowledge of potential non-infringement and with malicious competitive intent, its Notification Act could not be deemed a "legitimate exercise of rights." Therefore, the defense failed, and the act constituted illegal unfair competition. The court also found Y1 was clearly negligent.

Key Legal Issues and Analysis

This case delves into the delicate balance between enforcing IP rights and competing fairly.

1. When Do Infringement Claims Become "False Information"?

The judgment confirms that assertions of IP infringement, even if common in disputes, can constitute actionable "false information" under the UCPA if the product is ultimately found non-infringing. It suggests courts will look beyond whether the statement was framed as fact or opinion ("Product X infringes" vs. "We believe Product X infringes") and focus on the objective truth and the potential impact on the competitor's reputation. Making unfounded infringement claims carries legal risk in Japan.

2. Demarcating the "Legitimate Exercise of Rights":

This is the critical battleground in such cases. When do infringement warnings qualify for this defense? The Tokyo District Court's analysis highlights several key factors:

- Good Faith Belief: The sender must possess a reasonable, good-faith belief in the validity of their infringement claim at the time the communication is made. Receiving credible evidence or strong arguments casting doubt on infringement before sending warnings significantly undermines this element, as seen with Y1 receiving X's arguments.

- Primary Purpose: Is the main goal to protect legitimate IP rights through established procedures, or is it to disrupt the competitor's business, damage its reputation, or gain leverage outside the normal legal process? The court found Y1's purpose was the latter – preemptively harming X's market position for Caterpyrun+.

- Timing and Context: The sequence of events matters. Sending warnings immediately after receiving detailed non-infringement arguments, or using judgments about different products or circumstances as justification against a new product, weighs heavily against legitimacy.

- Malice/Bad Faith: While perhaps not always essential, a finding of malicious intent, as in this case, makes it extremely difficult to argue the actions were a legitimate exercise of rights. The court viewed Y1's strategic use of the prior interim judgment and the timing of the letters as evidence of bad faith.

3. Negligence vs. Intent:

While this judgment focused heavily on Y1's knowledge and perceived malicious intent to negate the "legitimate exercise" defense, it's worth noting that liability under UCPA Art. 2(1)(22) can potentially arise from negligence as well. A party might be found liable if they were negligent in failing to adequately investigate or verify their infringement claim before disseminating harmful allegations. However, the "legitimate exercise" defense analysis often blurs the lines between intent and negligence, as a lack of reasonable investigation can itself suggest a lack of good faith.

4. Mitigating Risks for Rights Holders:

How can IP owners communicate with potential infringers or their supply chain without risking UCPA liability?

- Thorough Pre-Action Investigation: Conduct comprehensive technical and legal analysis before asserting infringement.

- Solid Basis: Ensure claims are based on well-reasoned interpretations of patent claims and the accused product, not speculation or overreach.

- Targeted Communication: Consider initially contacting the alleged primary infringer directly rather than immediately sending broad notices to customers/distributors, which carries higher reputational impact and risk.

- Clarity and Specificity: Warning letters should clearly identify the IP right, the specific product(s) accused, and the basis for the infringement claim. Avoid vague or overly broad accusations.

- Good Faith Negotiation: Engage in genuine attempts to resolve the dispute before escalating communications to third parties.

Implications for US Businesses

The principles from this case have direct relevance for US companies involved in the Japanese market:

- IP Enforcement Strategy: Design your Japanese IP enforcement strategy carefully. Aggressive tactics, especially sending infringement notices to a competitor's customers or distributors without a solid, good-faith basis, can lead to counterclaims under the UCPA for reputational harm. The potential damages and injunctions under the UCPA should be factored into risk assessments.

- Responding to Warnings: If your company or its Japanese partners receive infringement warning letters from a competitor, assess their validity critically. If the claims appear baseless or strategically motivated to disrupt your business, consider potential countermeasures under the UCPA.

- Due Diligence is Key: Before sending any infringement-related communications, especially to third parties, perform rigorous due diligence on the technical merits and the legal strength of your claim regarding the specific product in question. Document this diligence.

- Consider the Timing: Be particularly cautious about sending warnings shortly after receiving information (e.g., court filings, detailed letters) from the target company that casts significant doubt on your infringement claim. Such timing can be interpreted as evidence of bad faith.

- Strategic Communication Choices: Weigh the risks and benefits. A direct approach to the competitor might be prudent initially. If warnings to third parties are deemed necessary, ensure they are factually accurate, legally well-founded, and sent in good faith pursuit of legitimate rights enforcement, not primarily for competitive disruption.

Conclusion

The Tokyo District Court's ruling in the no-tie shoelace dispute serves as a potent illustration of the interplay between intellectual property enforcement and unfair competition law in Japan. While vigorously defending IP rights is essential, the case demonstrates that utilizing infringement claims as a strategic weapon to damage a competitor's reputation, particularly when lacking a solid, good-faith belief regarding the specific product or acting with malicious intent, can cross the line into unlawful unfair competition. The "legitimate exercise of rights" is a shield, but it is not absolute and can be pierced by evidence of bad faith or unreasonable conduct. For businesses operating in the highly competitive Japanese market, this underscores the critical need for a balanced and meticulously planned approach to IP disputes, ensuring that enforcement actions are not only legally grounded but also pursued in a manner consistent with principles of fair competition.

- Protecting Innovation: Patent Enforcement and Management Strategies in Japan

- Digital Deception or Fair Play? Applying Japan’s Premiums and Representations Act to Online Advertising

- Japan-US-EU Advertising Regulation: A Comparative Look at Japan’s Keihyoho

- JPO — Unfair Competition Prevention Act (English outline)

- METI — Guidelines on Acts Damaging a Competitor’s Reputation

- Cabinet Office — IP Enforcement Q&A (Warning Letters)