Protecting the Past: Who Has the Right to Sue When a Historic Site Designation is Revoked in Japan?

Judgment Date: June 20, 1989, Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

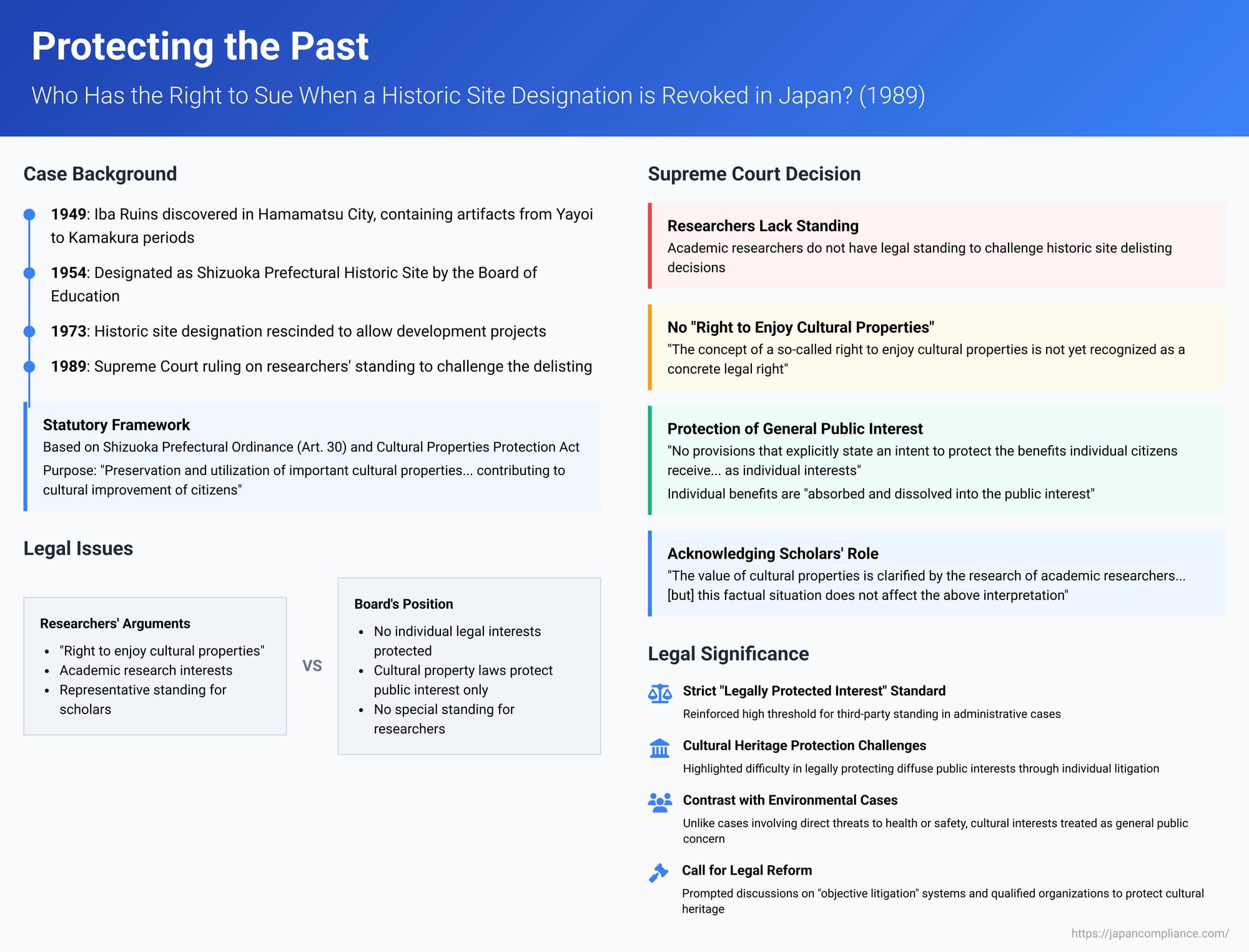

The preservation of cultural heritage is a widely recognized public good. However, decisions by administrative bodies to designate, or more controversially, to de-designate sites of historical or cultural importance can lead to significant disputes. A key legal question that arises is who has the right – or "standing" – to challenge such administrative decisions in court. A 1989 Supreme Court decision concerning the delisting of the Iba Ruins in Shizuoka Prefecture addressed this issue directly, particularly concerning the standing of academic researchers deeply involved with the site.

The Iba Ruins: A Rich Archaeological Site and its Designation

The Iba Ruins, located in Hamamatsu City, Shizuoka Prefecture, were first discovered in 1949 on the site of a former railway factory. Subsequent archaeological investigations revealed a wealth of artifacts dating from the Yayoi period (roughly 300 BCE to 300 CE) to the Kamakura period (1185–1333 CE). Discoveries in the surrounding areas further indicated that Iba was part of a major and significant ancient settlement complex[cite: 1].

Recognizing its importance, Y (the Shizuoka Prefectural Board of Education) designated the Iba Ruins as a Shizuoka Prefectural Historic Site in March 1954[cite: 1]. This designation was made under the authority of the Shizuoka Prefectural Ordinance for the Protection of Cultural Properties ("the Ordinance"), which itself was enacted based on the national Cultural Properties Protection Act ("the Law")[cite: 1]. The purpose of the Ordinance, as stated in its Article 1, was to take necessary measures for the preservation and utilization of important cultural properties within the prefecture (other than those already designated under the national Law), thereby contributing to the cultural improvement of the prefectural citizens and the advancement of Japanese culture[cite: 1]. Under Article 29, Paragraph 1 of the Ordinance, the Board of Education had the power to designate important prefectural historic sites. Conversely, Article 30, Paragraph 1 allowed the Board to rescind such a designation if the site had "lost its value" or for "other special reasons"[cite: 1].

Delisting for Development: The Spark for Legal Action

In November 1973, Y (the Board of Education) made the decision to completely rescind the historic site designation for the Iba Ruins. The stated reason for this delisting was the necessity of accommodating development projects, including the elevation of the nearby Hamamatsu railway station[cite: 1]. This decision was made on the grounds that these development needs constituted "other special reasons" as per Article 30 of the Ordinance.

This delisting spurred legal action from X et al., a group of academic researchers. These individuals had made the Iba Ruins a subject of their scholarly research and had been actively involved in movements advocating for the site's preservation[cite: 1]. They filed a lawsuit seeking the revocation of the Board of Education's decision to delist the Iba Ruins, arguing that the site still possessed significant cultural value and that the reasons for delisting did not meet the criteria set forth in the Ordinance.

The central preliminary issue in the case became whether X et al., as academic researchers with a strong interest in the site, had the necessary legal standing (plaintiff standing, or 原告適格 - genkoku tekkaku) to bring such a lawsuit. X et al. argued their standing on three main grounds[cite: 1]:

- A "right to enjoy cultural properties" (文化財享有権 - bunkazai kyōyūken), which they asserted as a right held by citizens.

- The personal academic research interests of scholars, which they claimed were directly harmed by the delisting.

- A form of "representative standing," suggesting that scholars, due to their expertise and role in understanding cultural heritage, should be able to sue on behalf of the public to protect such assets.

Both the Shizuoka District Court (First Instance) and the Tokyo High Court (Second Instance) ruled against X et al., finding that they lacked the necessary standing to challenge the delisting. X et al. then appealed to the Supreme Court[cite: 1].

The Supreme Court's Decision (June 20, 1989): Standing Denied

The Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, dismissed the appeal by X et al., thereby upholding the lower courts' decisions that the researchers lacked standing. The Court addressed each of the plaintiffs' arguments for standing:

I. No Concrete "Right to Enjoy Cultural Properties"

Regarding the claim of a "right to enjoy cultural properties," the Supreme Court stated succinctly: "The concept of a so-called right to enjoy cultural properties is not yet recognized as a concrete legal right. Therefore, the appellants' constitutional arguments, which presuppose that this is a concrete right, are without merit." [cite: 3] This effectively dismissed the notion that a general public interest in enjoying cultural heritage translates into an individual, legally enforceable right sufficient to grant standing in this context.

II. Academic Research Interests Not Individually Protected by the Relevant Laws

The Court then turned to the argument that the researchers' academic interests were harmed. It examined the purpose and provisions of both the national Cultural Properties Protection Act and the Shizuoka Prefectural Ordinance[cite: 3].

- The Court found that these laws primarily aim to protect and utilize cultural properties for the broader public benefit – specifically, the cultural improvement of citizens and the advancement of Japanese culture in general[cite: 3].

- It determined that there were "no provisions that explicitly state an intent to protect the benefits individual citizens or residents receive from the preservation and utilization of historic sites and other cultural properties as individual interests of those persons"[cite: 3]. Instead, the Court reasoned, these laws intend for such individual benefits to be "absorbed and dissolved into the public interest," with protection achieved through the realization of that broader public good[cite: 3].

- Furthermore, the Court found "no provisions that can be construed as giving special consideration to the protection of the academic research interests of scholars" beyond the general benefits that all citizens might derive[cite: 3].

- While acknowledging the practical reality that "the value of cultural properties is clarified by the research of academic researchers, and that the cooperation of academic researchers is indispensable for their preservation and utilization," the Court stated that this "factual situation does not affect the above interpretation" of the law's protective scope[cite: 3].

- Therefore, the Court concluded that even though X et al. were academic researchers who had studied the Iba Ruins, they did not possess a "legal interest" under the relevant statutes to seek the revocation of the historic site delisting disposition and thus lacked standing[cite: 3].

III. No "Representative Standing" for Scholars

Finally, the Supreme Court rejected the argument that academic researchers should be granted a form of "representative standing" to sue on behalf of the public to protect cultural properties. The Court stated that it was "difficult to construe such academic researchers as falling under 'persons who have a legal interest' to seek the revocation of the said disposition as provided in Article 9 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act, and moreover, there are no provisions in the Ordinance, the Act, or other current laws and regulations that can be construed as recognizing such representative standing as argued." [cite: 3]

The "Legally Protected Interest" Standard and Its Application

This judgment is a significant example of the Japanese Supreme Court's application of the "legally protected interest" (法律上の利益 - hōritsujō no rieki) standard for determining plaintiff standing in administrative litigation. This standard, established in earlier precedents and later codified in Article 9 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA), requires a plaintiff to show that a challenged administrative disposition infringes upon their "rights" or "legally protected interests."

For a third party (someone not the direct addressee of the disposition) to establish standing based on a "legally protected interest," the Supreme Court generally requires a showing that the specific law authorizing the administrative action in question intends to protect the concrete, individual interests of the plaintiff (or a class of persons to which the plaintiff belongs), and not merely general public interests. If a law is seen as protecting an interest only as part of the broader public good, any benefit an individual derives from it is often characterized as a "reflective interest" (hanshateki rieki), which is typically insufficient to grant standing.

In the Iba Ruins case, the Supreme Court meticulously analyzed the Cultural Properties Protection Act and the relevant Shizuoka Prefectural Ordinance. It concluded that these laws, while aiming to preserve cultural heritage, did so primarily for the benefit of the general public – for the "cultural improvement of citizens" and the "advancement of Japanese culture" – rather than to protect the specific, individual interests of researchers in being able to study a particular site, or a general "right to enjoy" such sites[cite: 3].

Critiques and Comparisons

This decision has been subject to significant academic discussion and criticism.

- Formalism vs. Substantive Role of Researchers: Some commentators have criticized the judgment as being overly formalistic[cite: 3]. They argue that it does not give sufficient weight to the actual, indispensable role that academic researchers play in the identification, evaluation, understanding, and ultimately, the protection of cultural heritage—a role often implicitly, if not explicitly, recognized within the broader framework of cultural property protection laws[cite: 3]. Denying them standing, it is argued, can weaken the mechanisms for safeguarding cultural assets.

- Contrast with Environmental Cases: The PDF commentary draws a contrast between this case and certain environmental law cases (such as the Niigata Airport noise litigation or the Monju nuclear reactor case) where courts have, at times, been more willing to find that statutes protect the individual interests of residents facing direct threats to their health or safety, even if those statutes also serve broader public interests[cite: 4]. In the Iba Ruins case, the interest in preserving a historic site for academic study or general cultural enjoyment was treated as a more diffuse public interest, not conferring individual standing on the researchers.

- The "Right to Enjoy Cultural Properties": The Court's outright rejection of a "right to enjoy cultural properties" as a concrete legal right for standing purposes was a significant statement[cite: 3]. While the concept might have moral or societal value, the Court found no basis for it as an individually enforceable legal right under the then-existing legal framework. The PDF commentary notes that while some scholars advocate for recognizing such a right, perhaps as a form of "historical environmental right," others agree it may be too abstract to ground individual standing[cite: 3].

The Challenge of Protecting Diffuse Interests

The Iba Ruins case highlights a persistent challenge in administrative law: how to ensure the legal protection of interests that are widely shared, diffuse, or primarily of a "public good" character, such as cultural heritage or general environmental quality. When laws are interpreted as protecting only the general public interest, it can be difficult for individuals or specific groups to establish the "legally protected individual interest" required for standing in traditional administrative appeal lawsuits.

The PDF commentary notes that in the face of such restrictive standing doctrines, particularly for diffuse interests, legal scholars have proposed various solutions[cite: 4]. One avenue is legislative reform, such as creating systems for "objective litigation" (客観訴訟 - kyakkan soshō). This could include, for example, empowering specific qualified organizations to bring lawsuits on behalf of the public interest to protect cultural heritage or the environment, thus bypassing the need for individual plaintiffs to demonstrate a direct and personal legal injury as narrowly defined by the courts[cite: 4].

Conclusion

The 1989 Supreme Court decision in the Iba Ruins delisting case stands as a significant precedent in Japanese administrative law, particularly concerning the standing of third parties to challenge decisions related to cultural heritage. By denying standing to academic researchers based on their scholarly interests or a general "right to enjoy cultural properties," the Court reinforced a strict interpretation of the "legally protected interest" requirement. It found that the relevant cultural property protection laws were primarily aimed at serving the general public interest, and did not confer specific, legally protected individual interests upon the plaintiffs in a manner sufficient to grant them standing to challenge the delisting decision.

The case underscores the hurdles faced by those seeking to protect diffuse public interests through individual litigation in Japan. While the legal landscape, including the Administrative Case Litigation Act, has seen some evolution since 1989, the fundamental requirement for plaintiffs to demonstrate a specific, legally protected individual interest remains a central tenet of standing doctrine, prompting ongoing debate about the most effective legal mechanisms for safeguarding shared public values like cultural heritage.