Japan Export-Control & Patent-Secrecy Reforms: 2025 Guide

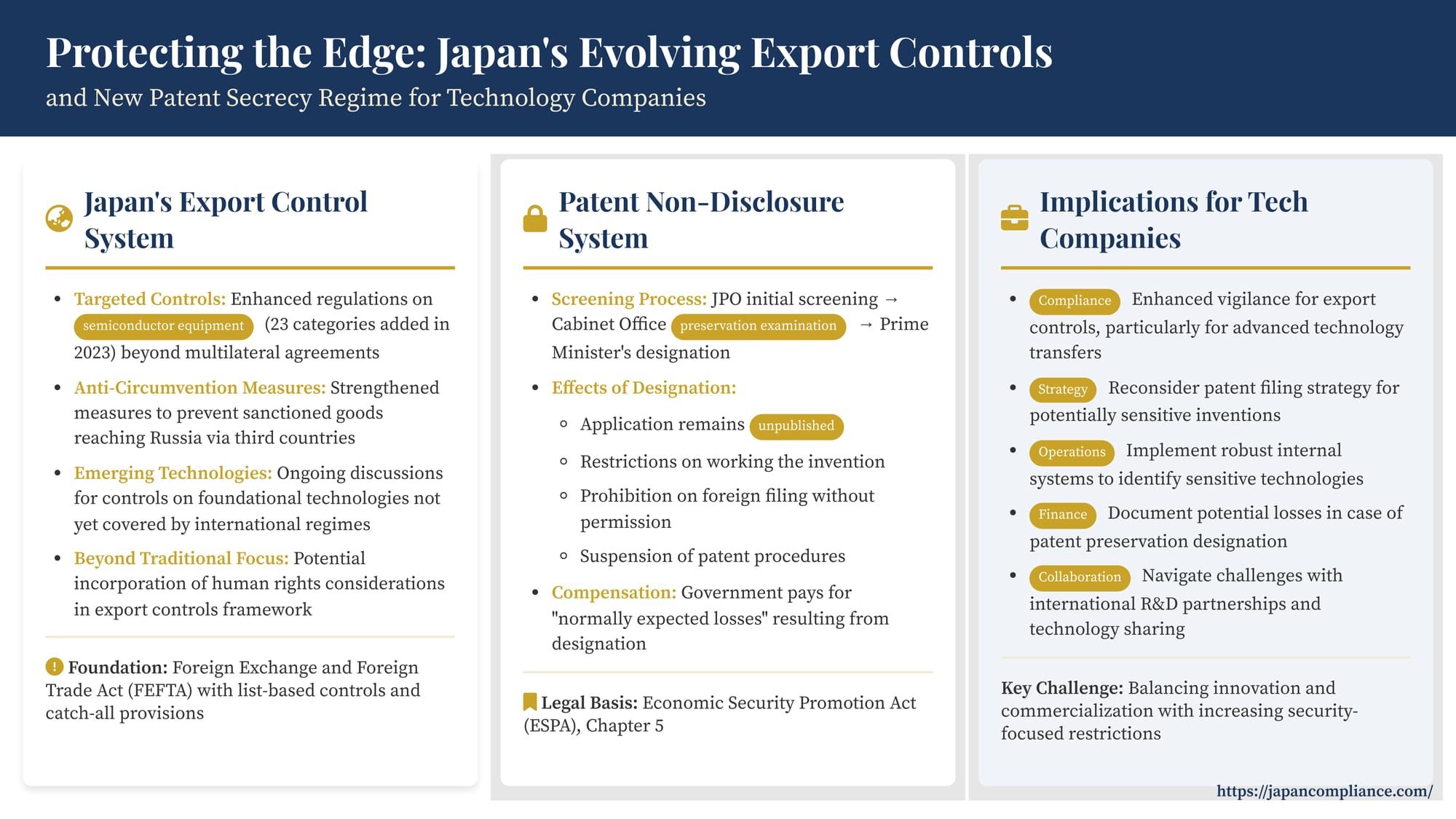

TL;DR: Japan is tightening export controls—adding chip-tool and emerging-tech items beyond multilateral lists—and has launched a patent secrecy regime under the Economic Security Promotion Act. Tech companies must update compliance programs, monitor “catch-all” triggers and weigh filing strategies to avoid secrecy orders.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Technology Control in the Age of Economic Security

- Part 1: Japan’s Transforming Export Control System

- Part 2: Japan’s New Patent Non-Disclosure System

- Conclusion: Navigating the Intersection of Technology, Security, and Law

Introduction: Technology Control in the Age of Economic Security

The global landscape for technology development and trade is undergoing a profound transformation. National security concerns, geopolitical rivalries, and the desire to maintain competitiveness in critical and emerging technologies are increasingly shaping government policies worldwide. Japan, a major technological powerhouse, is actively participating in this shift, implementing significant reforms under its economic security agenda.

Two key areas experiencing substantial change are export controls and the protection of potentially sensitive inventions during the patenting process. Japan has recently enhanced its export control measures, particularly concerning advanced technologies like semiconductor manufacturing equipment, often in coordination with allies but sometimes moving beyond traditional multilateral frameworks. Simultaneously, under the Economic Security Promotion Act (ESPA) enacted in 2022, Japan introduced a patent non-disclosure (or secrecy) system, which allows the government to keep certain patent applications confidential if their publication could pose a risk to national security.

For technology companies, especially those operating internationally or with R&D activities involving Japan, these developments carry significant weight. They impact how technology can be shared across borders, how intellectual property is managed, and the compliance landscape for international trade. This article explores the key features and implications of Japan's evolving export control system and its new patent secrecy regime.

Part 1: Japan's Transforming Export Control System

Japan has long maintained an export control system primarily based on the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act (FEFTA, 外為法), designed to prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and the excessive accumulation of conventional arms. This system operates through two main mechanisms:

- List Controls: Regulating the export of specific goods and technologies listed in appended tables to relevant cabinet orders (e.g., the Export Trade Control Order, 輸出令), which are often sensitive dual-use items identified through multilateral export control regimes like the Wassenaar Arrangement, the Nuclear Suppliers Group, the Australia Group, and the Missile Technology Control Regime. Exports of listed items generally require prior permission from the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI).

- Catch-All Controls: A complementary system requiring export licenses even for non-listed items if the exporter knows (or is informed by METI – the "inform" provision) that the items might be used in connection with WMD development or certain conventional arms activities by specific end-users or for concerning end-uses.

Drivers of Recent Change

While rooted in international cooperation, Japan's export control policies are evolving in response to several factors:

- Geopolitical Dynamics: The intensifying technological competition between the United States and China, Russia's aggression in Ukraine, and related international sanctions have spurred Japan to reassess and strengthen controls on sensitive technologies that could be diverted for military purposes or undermine national security.

- Limitations of Multilateral Regimes: Traditional multilateral regimes, which operate on consensus, can be slow to adapt to rapidly emerging technologies. There's a growing recognition among like-minded countries of the need for more agile, sometimes plurilateral, approaches to control cutting-edge technologies not yet covered by existing lists.

- Domestic Economic Security Focus: The broader push under the ESPA to secure supply chains, protect critical infrastructure, and promote domestic innovation in key technologies naturally includes controlling the outflow of sensitive domestic innovations.

Key Developments and Trends

Recent years have seen notable shifts and enhancements in Japan's export control practices:

- Targeted Controls on Advanced Technologies (Beyond Multilateral Lists): A prime example is the strengthening of controls on semiconductor manufacturing equipment. In July 2023, Japan implemented revised regulations adding 23 categories of advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment (such as certain lithography, deposition, etching, and inspection tools) to its export control list. While presented as a general measure not targeting specific countries, this move was widely seen as aligning with similar controls imposed by the United States and the Netherlands, reflecting plurilateral coordination among key technology holders to restrict access to cutting-edge chipmaking capabilities, particularly for certain state actors. Further updates occurred in August 2024, adding or refining controls on other items outside the scope of existing multilateral agreements, indicating a willingness to act unilaterally or plurilaterally when deemed necessary for national security.

- Combating Circumvention (Russia Sanctions Example): The implementation of extensive sanctions against Russia following its invasion of Ukraine highlighted the challenge of circumvention – where controlled goods reach the sanctioned destination via third countries. Japan, along with G7 partners, has focused on tackling this. Measures include identifying specific "Common High Priority Items" (items found in Russian weapons in Ukraine that are subject to controls) to raise awareness among businesses, enhancing due diligence expectations, and adding entities in third countries suspected of facilitating circumvention to Japan's export prohibition lists (effective December 2023 and June 2024). Policy discussions also suggest potentially strengthening catch-all controls even for exports to traditionally "low-risk" destinations (Group A countries) if diversion risks are identified.

- Focus on Emerging and Foundational Technologies: There is ongoing discussion within METI advisory bodies about the need for mechanisms to control emerging and foundational technologies that possess national security significance but are not yet regulated under international regimes. This points towards a potential future expansion of controls based on proactive technology assessments rather than solely relying on established lists.

- Potential Human Rights Linkage: While still largely in the discussion phase, there is growing international momentum, exemplified by the U.S.-led Export Controls and Human Rights Initiative launched at the Summit for Democracy, to consider human rights impacts when regulating dual-use technologies (e.g., surveillance technology). Japanese policy documents acknowledge these international trends, suggesting that human rights considerations might eventually become a more explicit factor in Japan's export control framework, although concrete measures are not yet in place.

Implications for Technology Companies

These evolving export controls present several key considerations for businesses:

- Heightened Compliance Vigilance: Companies must monitor not only changes stemming from multilateral regimes but also Japan-specific controls and plurilateral initiatives (like those related to semiconductors). Compliance programs need to be robust and adaptable.

- Impact on Technology Transfer: Stricter controls affect the export of hardware, software, and technical data/assistance, including "deemed exports" (technology transfer to foreign nationals within Japan). This impacts international R&D collaboration, global product launches, and employee mobility.

- Supply Chain Due Diligence: Increased focus on end-use, end-users, and circumvention requires more thorough vetting of customers, intermediaries, and transaction pathways, especially when dealing with sensitive technologies or destinations subject to heightened scrutiny.

- Strategic Planning: Potential restrictions on emerging technologies necessitate careful strategic planning around R&D investment, global manufacturing footprint, and market access.

Part 2: Japan's New Patent Non-Disclosure System

Complementing export controls, the ESPA introduced a system (Chapter 5) allowing certain patent applications to be kept secret for national security reasons. This system addresses the concern that the standard patent publication process could inadvertently reveal sensitive technologies with military or other security applications. It came into effect likely in the spring of 2024.

Rationale and Comparison

The fundamental idea is that while the patent system promotes innovation through disclosure, some inventions, if made public, could be exploited in ways that undermine Japan's security. This mirrors concepts like the Invention Secrecy Act in the United States, although the specific procedures differ. Prior to this system, Japan relied primarily on controlling the export of technology after a patent was filed or granted; this new system intervenes earlier in the IP lifecycle.

The Screening and Designation Process

- JPO Initial Screening: When a patent application is filed with the Japan Patent Office (JPO), it undergoes an initial screening to identify potentially sensitive subject matter based on certain International Patent Classification (IPC) codes related to technologies with potential security implications (e.g., nuclear technology, advanced materials, certain software).

- Referral to Cabinet Office: If the JPO identifies a potentially sensitive application, it refers the application to the Cabinet Office for a detailed "preservation examination" (保全審査, hozen shinsa).

- Preservation Examination: The Cabinet Office, in consultation with relevant ministries (e.g., Ministry of Defense, METI), assesses whether publishing the invention could create a risk of external actions harming the security of Japan and its citizens.

- Preservation Designation (保全指定, hozen shitei): If such a risk is confirmed, the Prime Minister, based on the Cabinet Office's assessment, can issue a preservation designation for the patent application.

Effects of a Preservation Designation

Once an application receives a preservation designation (becoming a "designated patent application"), several significant consequences follow (Articles 66-78):

- Secrecy: The application is not published (出願公開, shutsugan kōkai is suspended). The applicant is prohibited from disclosing the invention, except under specific circumstances permitted by the Prime Minister (Article 74).

- Restriction on Working: The applicant is generally prohibited from working (implementing) the invention, although permission may be granted by the Prime Minister, potentially with conditions (Article 73).

- Information Security Measures: The applicant must take appropriate measures to prevent the leakage of information related to the invention (Article 75).

- Suspension of Patent Procedures: Patent examination, decisions (grant or rejection), and registration are all put on hold for the duration of the designation (Article 66(7)).

- Foreign Filing Prohibition: Filing patent applications for the same invention in foreign countries is prohibited, unless permitted by the Prime Minister (Article 78). This is a crucial difference from standard patent procedures where applicants often file internationally soon after the initial domestic filing.

The designation is reviewed annually and can be maintained as long as the security risk persists.

Compensation for Losses (損失補償)

Recognizing that a preservation designation imposes significant restrictions on the applicant's property rights (the potential patent and the ability to exploit the invention) for the public good (national security), the ESPA mandates government compensation for resulting losses (Article 80). This aligns with Article 29(3) of the Japanese Constitution regarding just compensation for the taking of private property for public use.

- Basis: The government compensates for "normally expected losses" (通常生ずべき損失, tsūjō shōzubeki sonshitsu) incurred due to the preservation designation, such as those arising from the prohibition or restriction on working the invention.

- Types of Potential Losses: While specific guidelines are still evolving, potential categories include:

- Lost Profits: Revenue the applicant could reasonably have expected to earn by working the invention (domestically or internationally) or licensing it, had the designation not occurred.

- Wasted Expenses: Costs incurred in preparation for activities now prohibited by the designation, such as advanced preparations for foreign patent filings (e.g., translation costs). Although logically these are sunk costs, official Q&As suggest they might be considered compensable, potentially as a proxy for difficult-to-prove lost profits.

- Compliance Costs: Expenses incurred to implement the mandatory information security measures for the designated invention.

- Lost Licensing Royalties: If a third party uses the invention (perhaps independently developed or leaked), the applicant cannot assert patent rights (as no patent is granted) to claim royalties or damages during the designation period; this lost opportunity could be a basis for compensation.

- Challenges in Calculation: Quantifying "normally expected losses," especially lost profits for an invention that hasn't been commercialized (precisely because of the secrecy order), is inherently difficult and speculative. Unlike patent infringement damages where actual market data might exist, here the assessment relies on counterfactual scenarios. Some commentators have discussed whether R&D costs could serve as a minimum baseline or proxy for compensation, although official guidance has reportedly leaned against directly compensating R&D investment itself, viewing it as recoverable through anticipated profits. The burden of proving the quantum of loss rests with the applicant.

- Procedure: Applicants must file a claim for compensation with the Prime Minister. The government determines the appropriate amount. If dissatisfied, the applicant can file a lawsuit seeking an increase within six months of receiving the determination notice (Article 80(5)).

Implications for Technology Companies

The patent non-disclosure system introduces new strategic and operational considerations:

- Filing Strategy: Companies developing potentially sensitive or dual-use technologies need to consider the risk of their patent applications being subjected to secrecy orders. This might influence decisions about whether and where (Japan vs. another country) to file first, especially given the restriction on subsequent foreign filing after a designation.

- Internal Processes: Robust internal systems are needed to identify potentially sensitive inventions early, manage information securely, and comply with designation requirements if they arise.

- Commercialization Delays: A secrecy order prevents publication, patent grant, and often implementation, delaying or potentially eliminating commercial benefits from the invention, at least during the designation period.

- Compensation Uncertainty: While compensation is mandated, the process and calculation methods are complex and relatively untested. Securing adequate compensation for lost opportunities may be challenging and require detailed documentation and potentially litigation.

- International Collaboration: Sharing potentially sensitive technology developed under international collaboration might be complicated if a Japanese patent application covering it becomes subject to a secrecy order.

Conclusion: Navigating the Intersection of Technology, Security, and Law

Japan's recent moves to strengthen export controls and implement a patent secrecy system underscore the global trend of integrating economic and technological considerations into national security strategies. For technology companies, these changes necessitate a heightened awareness of the regulatory environment in Japan.

The enhanced export controls, particularly for advanced semiconductors and potentially other emerging technologies, require rigorous compliance programs and careful management of international technology transfer. The patent non-disclosure system adds a layer of complexity to IP strategy, requiring companies to weigh the benefits of patent protection against the risks of secrecy orders for sensitive inventions. While compensation mechanisms exist, their practical application and adequacy remain somewhat uncertain.

Successfully navigating this landscape requires proactive engagement: monitoring regulatory updates from METI, the Cabinet Office, and the JPO; implementing robust internal compliance and information security protocols; strategically managing IP filings; and carefully documenting potential losses should a patent application become subject to a secrecy order. As Japan continues to refine its economic security framework, technology companies must remain vigilant and adaptive to ensure both compliance and continued innovation.

- Fortifying the Chain: Japan’s Regulations on Critical Supply Chains and Infrastructure

- Navigating Japan’s New Security-Clearance System

- EU Battery Regulation: Global Reach—Impact on US & Japanese Supply Chains

- METI — Export-Control FAQ on Advanced Semiconductor Equipment (JP)

https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/anpo/semicon_faq.html