Protecting Stardom in Japan: Publicity Rights for Stage Names and Group Names

TL;DR

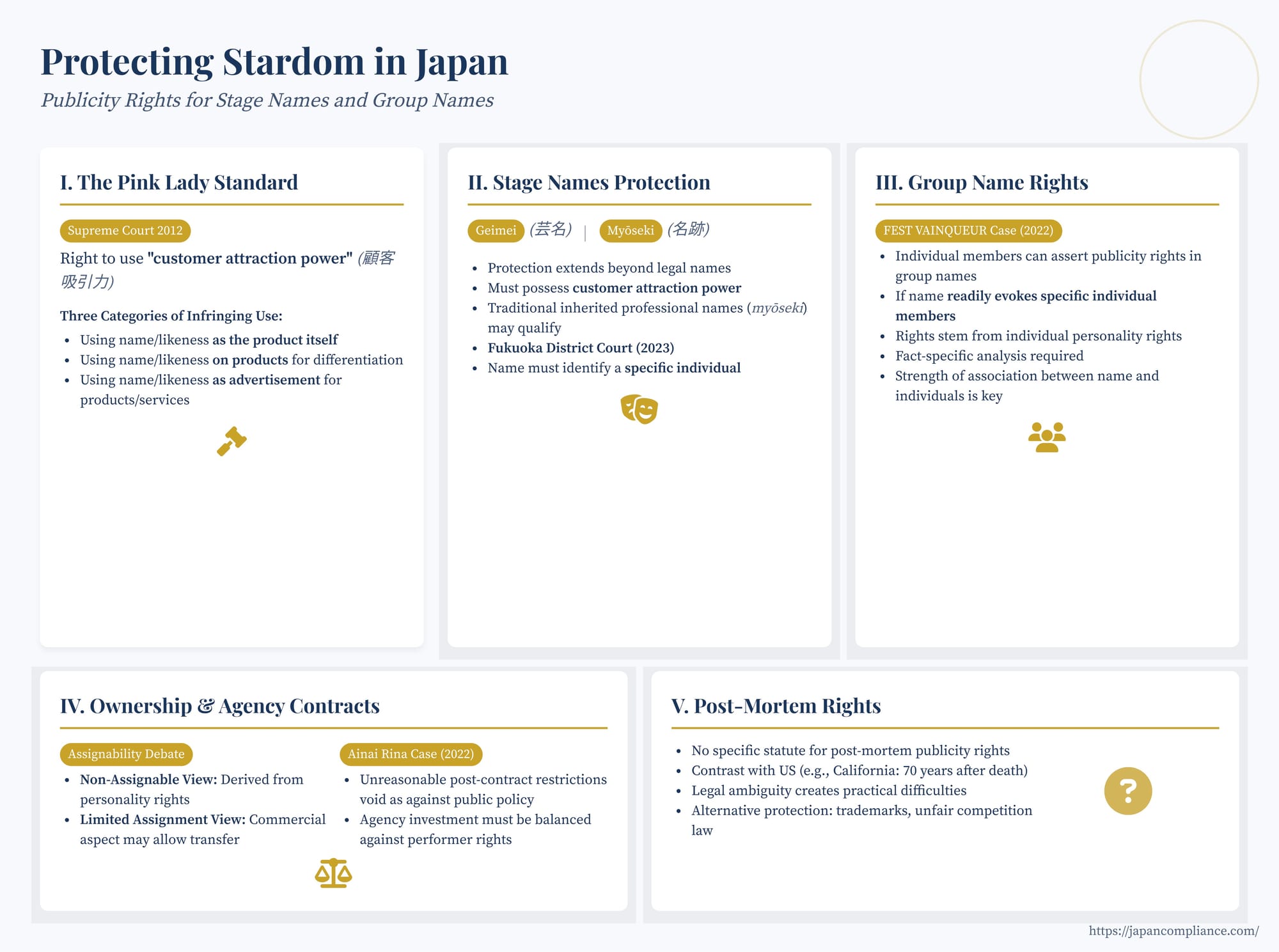

- Japan recognises publicity rights over stage names and, in some cases, group names when they embody “customer-attraction power.”

- Recent cases (FEST VAINQUEUR 2022, Ainai Rina 2022, Hayashiya Kikuō 2023) clarify that rights stem from individual personality, are hard to assign, and may void over-restrictive agency clauses.

- Businesses must obtain explicit, time-bound licences, avoid indefinite post-contract restrictions and prepare alternative IP (e.g., trademarks) where post-mortem rights are uncertain.

Table of Contents

- Understanding Publicity Rights in Japan: The Pink Lady Standard

- Stage Names (Geimei) and Professional Names (Myōseki)

- Group Names (グループ名)

- Ownership, Control, and Agency Contracts

- Publicity Rights After Death

- Conclusion

For entertainers, athletes, influencers, and other celebrities active in Japan, their name and likeness are not just identifiers but valuable commercial assets. The legal right protecting the commercial value of this identity is known as the "Right of Publicity" (パブリシティ権, paburishiti-ken). While distinct from fundamental privacy or portrait rights, publicity rights are crucial for controlling how a famous persona is used commercially. This protection extends beyond legal names to encompass stage names and even group names, though the application involves specific nuances under Japanese law, as highlighted by recent court decisions.

Understanding Publicity Rights in Japan: The Pink Lady Standard

The foundation for modern publicity rights in Japan was solidified by a landmark Supreme Court decision often referred to as the Pink Lady case (Supreme Court of Japan, February 2, 2012). In this judgment, the Court formally recognized the Right of Publicity as a legal right derived from constitutionally protected personality rights (jinkaku-ken).

The Court defined publicity rights as the exclusive right to utilize the "customer attraction power" (顧客吸引力, kokyaku kyūinryoku) associated with an individual's name, likeness, or other identity markers. It clarified that unauthorized use of someone's name or likeness constitutes an infringement – a tortious act – primarily in scenarios where the use is aimed exclusively at exploiting this customer attraction power. The Court outlined three main categories of infringing use:

- Using the name/likeness as the product itself (e.g., selling photos, posters, merchandise featuring the celebrity).

- Using the name/likeness on products with the purpose of differentiating those products (e.g., celebrity endorsements featured directly on packaging).

- Using the name/likeness as an advertisement for products or services.

This framework emphasizes that not every use of a famous person's identity is an infringement; the core issue is the unauthorized commercial capitalization on their fame and public recognition.

Stage Names (Geimei) and Professional Names (Myōseki)

Japanese law acknowledges that the protection of publicity rights is not limited to a person's legal name. It extends to any identifier that the public strongly associates with the individual, including widely recognized stage names (芸名, geimei) or pen names. If a stage name possesses customer attraction power linked to the specific entertainer, its unauthorized commercial use can infringe their publicity rights.

A more complex situation arises with traditional inherited professional names (myōseki, 名跡), common in arts like kabuki theatre or rakugo storytelling, where multiple individuals across generations might use the same prestigious name (e.g., Ichikawa Danjūrō). Can publicity rights attach to such names?

A recent district court case touched upon this (Fukuoka District Court, September 8, 2023, involving the name "Hayashiya Kikuō"). While primarily a trademark dispute, the court acknowledged in dicta that unauthorized use of such a famous myōseki could potentially infringe publicity rights or constitute misuse of a well-known indication under the Unfair Competition Prevention Act.

However, for publicity rights to be infringed, the name likely needs to identify a specific individual possessing customer attraction power. If a myōseki like "Ichikawa Danjūrō" is used generically, without clearly referencing the current holder (XIII) or a specific, famous predecessor (like Danjūrō XII), establishing infringement of a particular individual's publicity rights might be difficult. The right protects the commercial value linked to an individual's persona, not necessarily the lineage name in the abstract, unless that name has become inextricably linked in the public mind with one specific, famous holder.

Group Names (グループ名)

Can individual members of a band or group assert publicity rights related to the group's name? This presents challenges because the name identifies the collective entity. A key decision from the Intellectual Property High Court (FEST VAINQUEUR case, December 26, 2022) addressed this.

The court held that if a group name functions as identifying information for the members collectively, such that the name readily evokes specific individual members in the minds of the public, then those individual members can exercise publicity rights related to the group name, stemming from their own personality rights.

This ruling, however, leaves questions:

- Does every member need to be identifiable? What about large ensembles or groups with frequent member changes?

- Can former members assert rights if the name still strongly evokes them?

In the FEST VAINQUEUR case, the court looked at the specific band's history, activities, and recognition to infer that the name did, in fact, readily evoke the plaintiff members. This implies a fact-specific analysis is required, focusing on the strength of the association between the group name and the individuals claiming the right. The more a group name serves as a proxy for specific, identifiable members in the public consciousness, the stronger the case for individual members asserting publicity rights related to it.

Ownership, Control, and Agency Contracts

A frequent source of conflict in the Japanese entertainment industry revolves around who controls the publicity rights associated with stage or group names, especially when talent parts ways with their management agency.

Contractual Terms: Talent management agreements in Japan often include clauses stating that publicity rights, along with other intellectual property generated during the contract, "belong to" or are "assigned to" the agency.

The Assignability Debate: A significant legal debate exists on whether publicity rights, being derived from personality rights (jinkaku-ken), can be fully assigned or transferred like typical property rights.

- Non-Assignable View: Some court decisions, including the FEST VAINQUEUR case, explicitly state that publicity rights stem from non-transferable personality rights and thus cannot be assigned to the agency.

- Potentially Assignable (with Limits) View: Another line of thought, exemplified by the Ainai Rina case (Tokyo District Court, December 8, 2022), acknowledges the distinct financial value associated with publicity rights. This view suggests that while rooted in personality, the commercial aspect might theoretically allow for assignment. However, even if potentially assignable, such contractual clauses can be deemed void as against public policy (Civil Code Art. 90) if they unreasonably restrict the performer's professional activities or economic interests without adequate justification or compensation.

In the Ainai Rina case, the court examined a clause claiming the agency "primitively" acquired all rights, including publicity rights, arising from the performer's activities, without limitation. The court found this clause, particularly concerning post-contract control, to be excessively restrictive and lacking sufficient justification (like clear compensation for the rights transfer beyond normal management services or reasonable recoupment of specific investments), rendering the publicity rights assignment portion void under public policy.

Post-Contract Use of Names: Contracts also commonly restrict performers from using their established stage name after leaving the agency without permission. The Ainai Rina court also addressed such a clause, finding that an indefinite, post-contract ban on the performer using the stage name given to her by the agency was, under the circumstances, an unreasonable restraint and void under public policy.

Agency Investment: Agencies often justify restrictive clauses by citing the substantial investment made in launching and promoting talent, including building the reputation associated with a name. While courts acknowledge the need for agencies to recoup legitimate investments, the trend suggests that indefinite restrictions on a performer's core identity (their professional name) after contract termination are viewed unfavorably, especially without clear, fair compensation or justification tied directly to unrecouped investment. Alternative mechanisms, like limited-term revenue sharing post-departure, are sometimes seen as more proportionate means of addressing investment recovery.

Publicity Rights After Death

A significant area of uncertainty in Japanese law is the status of publicity rights after the personality holder's death.

- No Clear Post-Mortem Rights: Unlike some jurisdictions, Japan currently has no specific statute recognizing post-mortem publicity rights that can be inherited or managed by an estate. Privacy and portrait rights, being elements of personality rights, are generally considered to extinguish upon death (though courts may protect family members' feelings of reverence against egregious misuse of a deceased person's image).

- US Contrast: This contrasts with states like California and New York, which have enacted legislation granting inheritable post-mortem publicity rights for deceased celebrities, typically lasting for a set number of years (e.g., 70 years after death in California).

- Practical Problems: This legal ambiguity in Japan creates practical difficulties. When a famous entertainer dies, questions arise about who has the authority to license their name/likeness for commercial purposes (e.g., tribute merchandise, biographical films, digital recreations) or to sue for unauthorized uses. Without clear legal succession, the commercial value associated with the deceased's identity risks falling into a legal grey area or becoming freely exploitable.

- Potential Alternatives: In the absence of specific post-mortem publicity rights, potential avenues for protection might include trademark law (if the stage name or likeness was registered as a trademark for relevant goods/services) or unfair competition law (if the name/likeness continues to function strongly as a source identifier for related ventures).

Conclusion

The Right of Publicity is a critical legal concept for entertainers and their business partners in Japan. Japanese courts recognize its applicability to established stage names and, increasingly, to group names where a strong link to individual members exists. However, significant legal debates continue regarding the ownership, control, and assignability of these rights, particularly within the context of talent-agency relationships and contract termination. The lack of clear post-mortem publicity rights also presents ongoing challenges. For businesses involved in Japan's vibrant entertainment industry, understanding these evolving legal principles and ensuring contractual clarity are essential for effectively managing and protecting the valuable commercial aspect of celebrity identity.

- False IP Takedowns on Japanese E-Commerce Platforms: UCPA Liability & Risk-Control Guide

- Who Owns AI-Generated Works in Japan? Copyright, Authorship & Article 2 Criteria Explained

- Antitrust Green Lights?: Navigating Sustainability Collaborations in Japan

- Agency for Cultural Affairs – Portrait & Publicity Rights FAQ (Japanese)