Protecting Innovation: Patent Enforcement and Management Strategies in Japan

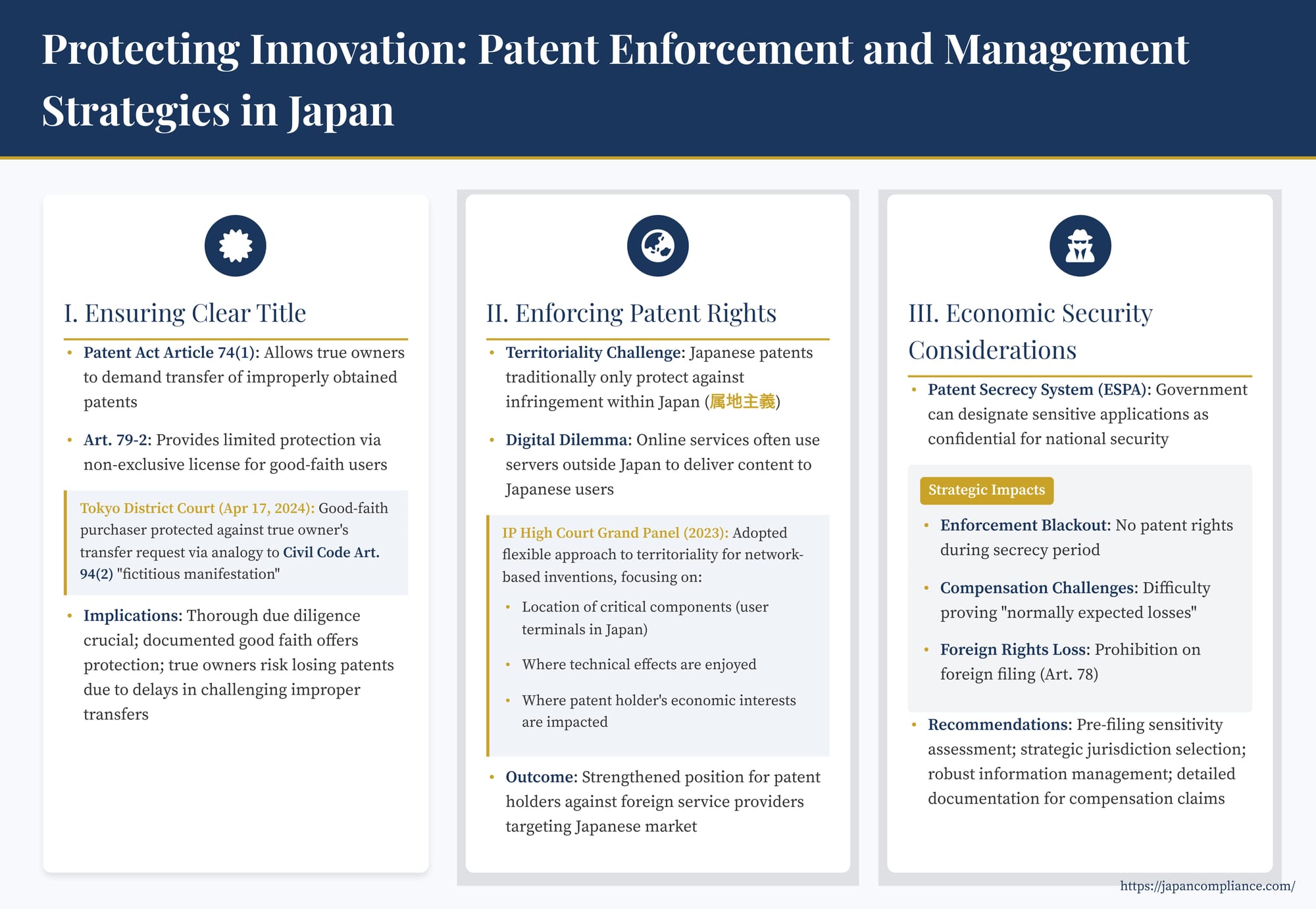

TL;DR: Winning the Japanese market demands more than filing patents. Recent court rulings strengthen good-faith purchaser protection and expand infringement reach to foreign digital services, while a new patent-secrecy regime may block publication and foreign filing. Clear title, cross-border enforcement tactics and secrecy-order risk management now form a three-pillar strategy.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Securing Technological Advantage in a Key Market

- Part 1: Ensuring Clear Title – Patent Ownership and Transfer Issues

- Part 2: Enforcing Patent Rights – The Cross-Border Digital Challenge

- Part 3: The Overlay of Economic Security – Patent Secrecy Considerations

- Conclusion: A Multi-faceted Approach to Patent Strategy in Japan

Introduction: Securing Technological Advantage in a Key Market

Japan stands as a global leader in innovation and a critical market for technology-driven industries. For international companies, securing and effectively managing intellectual property, particularly patents, within Japan is fundamental to maintaining a competitive edge, protecting investments in R&D, and enabling market access. However, navigating Japan's patent landscape requires understanding its specific legal nuances concerning ownership, transfer, enforcement, and the increasing overlay of economic security considerations.

Recent legal developments highlight the complexities involved. Court decisions are refining the rules around acquiring patent rights from potentially flawed titles and enforcing Japanese patents against infringing activities that cross borders, especially in the digital realm. Furthermore, new legislation aimed at economic security, such as the patent non-disclosure system, adds another layer of strategic consideration for companies dealing with potentially sensitive technologies.

This article explores key strategies and recent developments relevant to managing and enforcing patent rights in Japan. We will examine challenges related to patent ownership transfers, drawing insights from a notable 2024 court decision, and delve into strategies for enforcing patents against cross-border digital infringement, guided by a significant 2023 IP High Court ruling. Finally, we will touch upon how Japan's new patent secrecy regime interacts with these traditional IP management concerns.

Part 1: Ensuring Clear Title – Patent Ownership and Transfer Issues

Securing unambiguous ownership is the foundation of any patent strategy. In Japan, the right to obtain a patent originally belongs to the inventor(s), but this right is transferable (e.g., through employment agreements or specific assignments). Once granted, the patent right is registered, and registration serves as a key element in establishing ownership against third parties. However, complications can arise if the chain of title is defective.

The Challenge of Defective Title and Third-Party Rights

What happens if a patent is granted and registered to an entity (Party B) that did not legitimately acquire the right to obtain the patent from the true owner (Party X), perhaps due to an invalid assignment by an unauthorized individual (Party A)? Japan's Patent Act provides a specific remedy in such situations.

- Patent Act Article 74(1): Introduced in 2011, this article allows the person truly entitled to obtain a patent (the original inventor or their legitimate successor, Party X) to demand that the patent registration be transferred from the person who improperly obtained it (Party B). This applies to cases of application by an unauthorized person (冒認出願, bōnin shutsugan) or violations of joint application requirements (共同出願違反, kyōdō shutsugan ihan).

This provision aims to restore the patent to its rightful owner. However, the situation becomes more complex when a third party subsequently acquires the patent from the illegitimate registrant.

- Patent Act Article 79-2: This article provides specific protection for a third party who, in good faith, acquired and worked the patent (or prepared to do so) before the true owner filed the transfer request under Article 74(1). This protection, however, is limited to granting the third party a statutory non-exclusive license (通常実施権, tsūjō jisshiken) to continue working the invention under reasonable conditions. It does not protect the third party's ownership claim itself.

Can a good-faith purchaser (Company Y) who acquired the patent from the illegitimate registrant (Party B) assert broader ownership rights against the true owner (Company X), potentially overriding the transfer claim under Article 74(1)? This question was central to a recent court decision.

Case Study: Protecting Good-Faith Purchasers (Tokyo District Court, April 17, 2024)

This case (Tokyo District Court, Reiwa 4 (Wa) No. 19222) involved a complex chain of title dispute.

- Background: Company X was the original owner of the right to obtain a patent. An individual (Party A) lacking proper authority purported to transfer this right to Party B. Party B successfully obtained the patent registration. Subsequently, Party B transferred the registered patent right to Company Y (via an intermediary company). After Company X successfully invalidated Party A's unauthorized actions in separate proceedings, it sued Company Y under Patent Act Article 74(1) to compel the transfer of the patent registration back to Company X.

- Company Y's Defense: Company Y argued it was a good-faith purchaser for value without negligence. It claimed protection based on an analogy to Article 94(2) of the Civil Code. This article protects third parties who rely in good faith on a "fictitious manifestation of intent" (a false appearance of a legal relationship created with the original party's involvement or acquiescence). Company Y argued that Company X bore some responsibility for the false appearance of Party B's ownership persisting and that Y had relied on this appearance in good faith.

- The Legal Conflict: Could the general principle of protecting bona fide purchasers relying on a false appearance (Civil Code Art. 94(2) analogy) effectively block the true owner's specific statutory right to reclaim the patent under Patent Act Art. 74(1)? Did the specific, limited protection offered by Patent Act Art. 79-2 (a non-exclusive license) preclude the application of broader Civil Code protections?

- The Court's Decision: The Tokyo District Court ruled in favor of Company Y, denying Company X's transfer request. It held that an analogy to Civil Code Article 94(2) can be applied even in the context of a Patent Act Article 74(1) claim. The court's reasoning included:

- Articles 79-2 and 94(2) address different situations and have different requirements/effects. The Patent Act does not explicitly state that Article 79-2 displaces general third-party protection rules under the Civil Code.

- The court found that Company X had a degree of culpability (帰責性, kiseki-sei) in the creation and persistence of the false appearance of Party B's title, primarily due to internal issues allowing Party A's initial actions and delays in challenging them.

- It found that Company Y (and its intermediary) had acted in good faith and without negligence (善意無過失, zen'i mukashitsu) in acquiring the patent, having relied on due diligence performed by patent attorneys and the official registration status.

- Therefore, applying the analogy to Civil Code Article 94(2), the court concluded that Company X could not assert its underlying true ownership against the protected good-faith purchaser, Company Y.

Implications for Patent Management

This decision carries significant weight for managing patent ownership and transactions in Japan:

- Risk for True Owners: Even if a patent was initially obtained improperly, the true owner's ability to reclaim it under Article 74(1) can be defeated if a subsequent purchaser qualifies for protection under the Civil Code Article 94(2) analogy. This risk is heightened if the true owner is deemed to have contributed, even passively through delay, to the false appearance of title.

- Importance of Due Diligence (Purchasers): For entities acquiring patents, thorough due diligence regarding the chain of title remains crucial. However, this decision suggests that demonstrating good faith reliance on the patent register and reasonable investigative steps (like using patent attorneys) can provide strong protection against later claims by an original "true owner."

- Shift in Remedies: If a good-faith purchaser is protected under the Article 94(2) analogy, the true owner's primary recourse shifts from reclaiming the patent itself to seeking monetary damages from the party who wrongfully transferred the right initially (Party A or B in the example).

Part 2: Enforcing Patent Rights – The Cross-Border Digital Challenge

Patent rights are inherently territorial (属地主義, zokuchi-shugi), meaning a Japanese patent generally provides protection only against infringing acts occurring within Japan. This principle faces challenges in the digital age, where online services often involve components (like servers) located outside Japan delivering content or functionality to users inside Japan. When does the operation of such a service constitute infringement of a Japanese patent?

The Legal Framework and the Problem

- "Working" an Invention: The Patent Act defines infringement based on the "working" (実施, jisshi) of the patented invention (Article 100 allows injunctions against those infringing or likely to infringe). For inventions covering systems or processes, "working" includes the use of that system or process (Article 2(3)(i)). For product inventions, it includes making, using, selling, importing, etc. (Article 2(3)(iii)).

- The Territoriality Issue: If a patented system involves a server outside Japan interacting with a user terminal inside Japan, where is the "use" of the system occurring for the purposes of Japanese patent law? Can the foreign server operator be held liable for infringement in Japan?

Case Study: Online Comment Streaming System (IP High Court, May 26, 2023)

This landmark decision (IP High Court, Reiwa 4 (Ne) No. 10046) addressed the territoriality issue head-on in the context of an internet service.

- Background: The plaintiff (X) held a Japanese patent for a "comment delivery system" designed to display user comments overlaid on streaming video, ensuring comments flowed across the screen without overlapping. The defendant (Y1) was a US-based company operating a video streaming service accessible to users in Japan. Y1's servers, located outside Japan, delivered video data and comment data separately to user terminals inside Japan. Software running on the Japanese user's terminal then processed this data to implement the patented method of displaying non-overlapping, scrolling comments synchronized with the video. X sued Y1 for patent infringement in Japan. The District Court initially dismissed the claim, finding the core processing occurred on servers outside Japan.

- The IP High Court's Approach: The IP High Court (Grand Panel) reversed the District Court, finding that infringement could occur within Japan. It rejected a rigid interpretation of territoriality and adopted a more flexible, holistic approach for network-based inventions:

- Focus on the System as a Whole: The court emphasized looking at the patented system in its entirety and where its essential functions are performed and effects are realized.

- Key Factors for Assessment: Whether the "working" (use/production) occurs "within the territory of Japan" should be determined by comprehensively considering factors such as:

- The location of system components critical to the invention's core functionality (in this case, the user terminals in Japan performing the crucial non-overlapping display).

- The location where the technical effects and benefits of the invention are enjoyed by users (primarily in Japan).

- The place where the infringing activity impacts the patent holder's economic interests (Japan, where the patent holder competes or licenses).

- The overall configuration and operation of the system (viewing the transmission from abroad and the reception/processing/display in Japan as an integrated act).

- Finding of Domestic Act: Applying these factors, the Grand Panel concluded that even though Y1's servers were located abroad, the patented system was essentially completed and put into use within Japan when the user terminals executed the key processing steps to display the comments as claimed. The service targeted Japanese users, the invention's benefits were realized in Japan, and this directly impacted the Japanese patent holder's market. Therefore, the operation of the service, viewed holistically, constituted an infringing act ("production" or "use" - the court used the term 生産 seisan, though "use" might seem more apt for a system claim) within Japanese territory.

- Consequences: The court granted an injunction prohibiting Y1 from delivering files from its foreign servers to user terminals in Japan in a manner that would cause the patented comment display functionality to be executed. It also affirmed the possibility of awarding damages based on this domestic infringement.

Implications for Enforcement Strategy

This IP High Court decision significantly strengthens the hand of patent holders in Japan seeking to enforce their rights against globally operated online services:

- Expanded Reach: Japanese system or method patents can be asserted against foreign entities if their service relies on essential components or produces key inventive effects within Japan, especially when targeting Japanese users.

- User-Side Focus: The location, function, and processing performed by user-side elements (computers, smartphones, client software) within Japan are now critical factors in establishing territoriality for infringement.

- Viable Enforcement Against Foreign Actors: Patent holders have a clearer basis for pursuing infringement actions (injunctions and damages) in Japanese courts against foreign service providers whose operations have the requisite connection to Japanese territory, based on the effects and user-side activities within Japan.

Part 3: The Overlay of Economic Security – Patent Secrecy Considerations

The enforcement and management of patents in Japan must now also consider the potential impact of the ESPA's patent non-disclosure system.

Recap of the System

As outlined previously, this system allows the Japanese government to place a secrecy order (preservation designation) on patent applications concerning technologies whose public disclosure could harm national security. This prevents publication, patent grant, foreign filing, and often implementation of the invention.

Impact on Patent Management and Enforcement

- Enforcement Blackout: A secrecy order creates an "enforcement blackout" period. Since no patent is granted while the order is in effect, the applicant cannot assert patent rights against any third party, even if that party independently develops or uses the same invention. This can leave valuable technology unprotected during the secrecy period.

- Compensation Challenges: While Article 80 mandates compensation for losses caused by the secrecy order, the practicalities are difficult. Proving the "normally expected losses" (lost profits, lost licensing opportunities) for an invention that was never commercialized or patented is inherently speculative. There's a risk that the compensation awarded may not fully reflect the invention's potential market value or strategic importance lost due to the delay and secrecy.

- Loss of Foreign Rights: The prohibition on foreign filing (Article 78) is particularly damaging for inventions with international market potential. By the time a secrecy order is lifted (if ever), the opportunity to secure patent rights in other key jurisdictions may be lost due to prior art publication or statutory bars. Quantifying this loss of global potential for compensation purposes is extremely challenging.

Strategic Considerations for Tech Companies

- Pre-Filing Assessment: Companies developing technologies in sensitive fields (especially those listed in JPO screening guidelines or relevant to defense/critical infrastructure) should internally assess the risk of a secrecy order before filing a patent application in Japan.

- Filing Strategy: The risk of a secrecy order might influence decisions on first filing jurisdiction. Filing first in a country without such a broad secrecy system might be considered, although this carries risks related to potentially violating deemed export rules or losing priority rights if not handled carefully. Alternatively, focusing on trade secret protection instead of patenting might be viable for certain highly sensitive inventions where disclosure risks outweigh patent benefits.

- Information Management: If an application becomes subject to review or designation, strict internal information control protocols are essential to comply with non-disclosure obligations (Article 75) and avoid severe penalties.

- Compensation Documentation: If subject to a secrecy order, meticulous documentation of potential market opportunities, licensing interest, development costs (even if not directly compensable, potentially useful contextually), and incurred compliance costs will be crucial for building a compensation claim.

Conclusion: A Multi-faceted Approach to Patent Strategy in Japan

Protecting and leveraging innovation through patents in Japan requires a sophisticated strategy that accounts for nuances in ownership rules, evolving enforcement doctrines for digital technologies, and the new layer of economic security regulations.

Recent court decisions underscore the importance of due diligence in patent transactions, as good-faith purchasers may gain protection even against true owners under certain circumstances, potentially limiting the effectiveness of statutory remedies like Patent Act Article 74(1). Simultaneously, the IP High Court's flexible approach to territoriality offers patent holders stronger tools to combat cross-border infringement by online service providers targeting the Japanese market.

Overlaying these traditional IP concerns is the patent non-disclosure system, which introduces strategic dilemmas regarding filing sensitive inventions and poses challenges for enforcement and compensation. Companies operating in technology sectors relevant to Japan must integrate these diverse legal considerations—ownership clarity, robust digital enforcement tactics, and awareness of national security regulations—into a comprehensive IP management strategy to effectively protect their innovations in this vital global market.

- Protecting Innovation: Patent Enforcement and Management Strategies in Japan

- Navigating Japan’s New Security-Clearance System

- Fortifying the Chain: Japan’s Regulations on Critical Supply Chains and Infrastructure

- Japan Patent Office — Guidelines on Patent Ownership & Chain of Title (JP)

https://www.jpo.go.jp/system/patent/gaiyo/tourokumondai_guideline.html