Protecting Famous Public Interest Marks in Japan: Lessons from the "OLYMBEER" Trademark Case

TL;DR

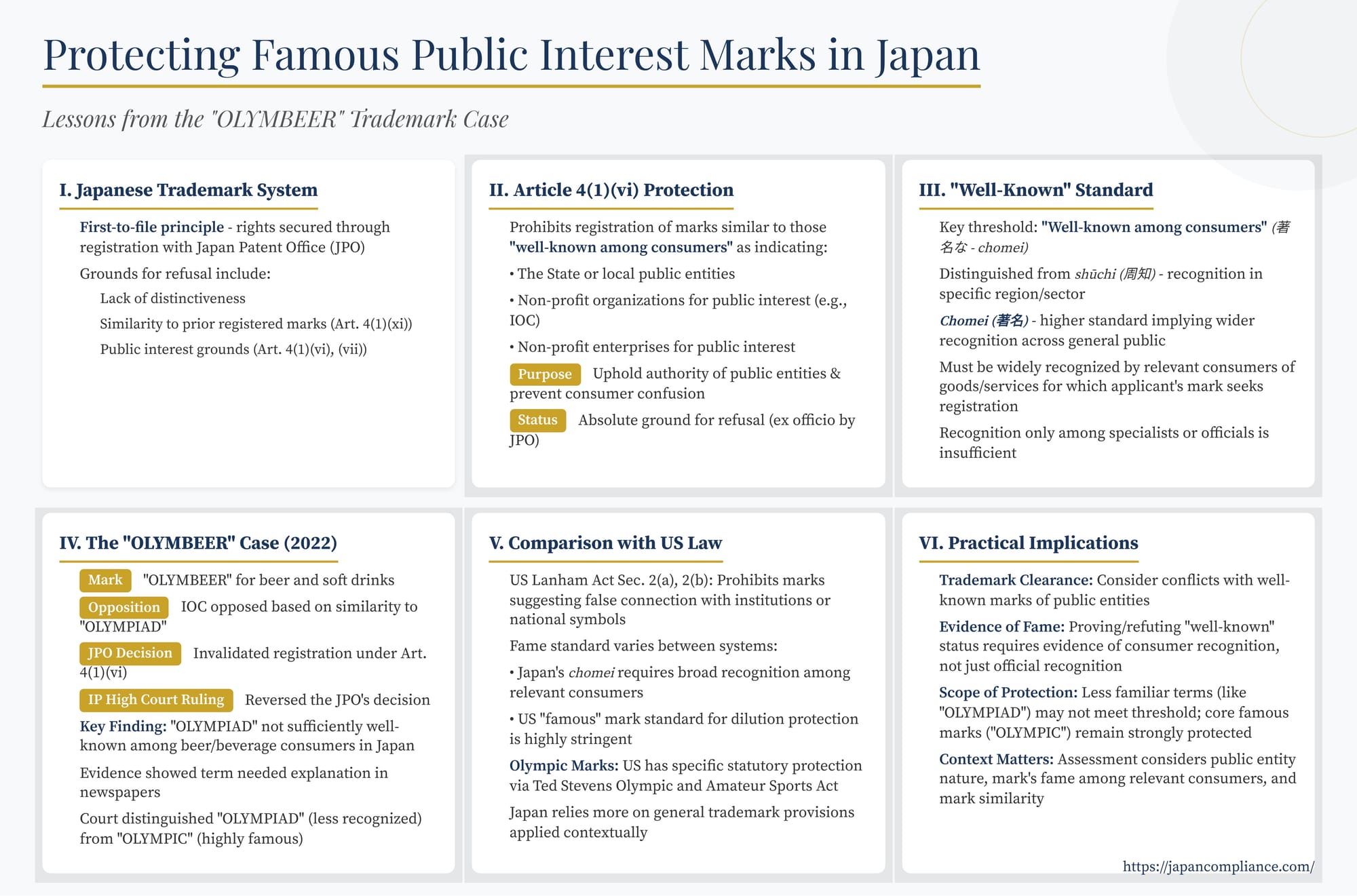

Japan blocks imitation of state or public-interest marks only if the original is “well-known” among relevant consumers. In the 2022 IP High Court “OLYMBEER” decision, the IOC’s term “OLYMPIAD” failed this fame test, so the beer mark survived. Truly famous marks like “OLYMPIC” still enjoy broad protection. Prove real marketplace recognition before invoking Article 4(1)(vi).

Table of Contents

- Japan's Trademark System: The Basics

- Specific Protection for Public Interest Marks: Article 4(1)(vi)

- The Crucial Standard: "Well-Known Among Consumers"

- The "OLYMBEER" Case: Testing the Fame Threshold

- Protection for Core Famous Marks like "OLYMPIC"

- Comparison with US Trademark Law

- Practical Implications for Businesses

- Conclusion

Building and protecting a strong brand identity through trademarks is paramount for businesses operating internationally. While general trademark principles regarding distinctiveness and similarity to prior marks are universal concerns, specific jurisdictions often have unique rules concerning marks that evoke associations with national symbols, public institutions, or internationally recognized events and organizations. Japan is no exception, offering particular grounds for refusal aimed at safeguarding the reputation and authority of such entities.

A recent decision by Japan's Intellectual Property (IP) High Court regarding an application for the trademark "OLYMBEER" provides valuable insight into how these rules are applied, particularly concerning the threshold required to establish a public interest mark as "well-known" enough to block the registration of similar marks. This article delves into the relevant provisions of the Japanese Trademark Act and analyzes the "OLYMBEER" case (IP High Court, December 26, Reiwa 4 - 2022), offering practical takeaways for businesses navigating trademark clearance and registration in Japan.

Japan's Trademark System: The Basics

Before examining the specifics of public interest marks, a brief overview of Japan's trademark system is helpful. Japan operates on a first-to-file principle, meaning that trademark rights are generally secured through registration with the Japan Patent Office (JPO), rather than through prior use (though use can be relevant in some contexts, like overcoming non-use cancellation actions or establishing secondary meaning). The JPO examines applications based on various criteria outlined in the Trademark Act (商標法, Shōhyō Hō). Common grounds for refusal include lack of distinctiveness (i.e., the mark is descriptive or generic for the goods/services) and similarity to prior registered trademarks owned by others (Article 4(1)(xi)).

Specific Protection for Public Interest Marks: Article 4(1)(vi)

Beyond these general grounds, the Japanese Trademark Act contains several provisions aimed at protecting public order or the integrity of official symbols. Among these is Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 6 (四条一項六号, yon-jō ikkō roku-gō). This article prohibits the registration of trademarks which are identical or similar to a mark "well-known among consumers" (著名な, chomei na) as indicating the State, a local public entity, specified non-profit organizations undertaking business for the public interest (such as the Japanese Red Cross or, relevantly here, international organizations like the International Olympic Committee - IOC), or non-profit enterprises undertaking business for the public interest.

The purpose of Article 4(1)(vi) is twofold:

- To uphold the authority and credibility of these public or public-interest entities by preventing third parties from appropriating their recognized symbols.

- To prevent consumer confusion regarding the source of goods or services, avoiding the mistaken impression that the product originates from or is endorsed by the public entity.

Importantly, this is an absolute ground for refusal based on public interest, meaning the JPO can raise it ex officio (on its own initiative), and it does not require an opposition or objection from the specific public entity itself (though such entities often do oppose applications they deem problematic). This distinguishes it from relative grounds like similarity to a prior registered mark (Art. 4(1)(xi)), which primarily protects the private rights of the earlier registrant.

The Crucial Standard: "Well-Known Among Consumers" (著名な)

The linchpin of Article 4(1)(vi) is the requirement that the public entity's mark be "well-known among consumers" (消費者の間に広く認識されている - shōhisha no aida ni hiroku ninshiki sarete iru, often shortened to 著名 - chomei). This raises the critical question: how "well-known" is required?

Japanese trademark law and practice distinguish between different levels of recognition:

- Shūchi (周知): Generally translated as "well-known," often implying recognition within a specific region or trade sector. This standard is relevant for certain protections under the Unfair Competition Prevention Act and for establishing broader rights for unregistered marks in some situations.

- Chomei (著名): Generally translated as "famous" or, in the context of Art. 4(1)(vi), "well-known." This typically implies a higher degree of recognition across the nation and among the general public or the relevant consumer base for the goods/services in question. This standard is used for stronger protection against dilution (under the Trademark Act or UCPA) and for the specific public interest ground in Art. 4(1)(vi).

For Article 4(1)(vi), the JPO Examination Guidelines and case law indicate that the mark must be widely recognized by the relevant consumers or traders of the goods/services for which the applicant's similar mark is seeking registration. It's not enough for the mark to be known only within the public entity itself or among specialists in a particular field. The recognition must extend broadly to the audience encountering the applicant's mark in the marketplace. Proving this level of widespread recognition can be a significant hurdle.

The "OLYMBEER" Case: Testing the "Well-Known" Threshold

The application of Article 4(1)(vi) and the interpretation of the "well-known" standard were central to the IP High Court's decision concerning the trademark "OLYMBEER".

Facts:

An applicant sought to register the standard character mark "OLYMBEER", along with its katakana transliteration "オリンビアー", for goods in Class 32, including beer and soft drinks. The JPO initially registered the mark. However, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) filed an opposition (later converted to an invalidation request). The JPO's Board of Appeal (BoA) ultimately invalidated the registration, primarily citing Article 4(1)(vi). The BoA found the mark similar to the IOC's identifier "OLYMPIAD" (and its Japanese equivalent オリンピアード, Orinpiādo).

JPO Board of Appeal's Reasoning:

The BoA determined that:

- The IOC is a non-profit organization working for the public interest.

- The mark "OLYMPIAD" was "well-known" in Japan at the time of the application/registration as indicating the Olympic Games and the IOC.

- The applied-for mark "OLYMBEER / オリンビアー" was confusingly similar to "OLYMPIAD / オリンピアード" in terms of appearance (shared "OLYM" prefix), sound (similar pronunciation), and concept (evoking the Olympics).

- Therefore, registration violated Article 4(1)(vi).

The IP High Court's Reversal:

The applicant appealed the JPO's invalidation decision to the IP High Court, which overturned the BoA's ruling and allowed the "OLYMBEER" mark to stand. The court's reasoning focused heavily on the interpretation of the "well-known" standard:

- "Well-Known" Status of "OLYMPIAD": The court conducted a detailed factual analysis of the recognition of "OLYMPIAD" in Japan. It acknowledged that the term appears in official documents like the Olympic Charter and was used in Japan's Olympic bidding files. However, the court found insufficient evidence that the term "OLYMPIAD" itself was widely recognized by the general consumers and traders of beer and beverages in Japan at the relevant time to meet the threshold for Art. 4(1)(vi).

- The court reasoned that the Olympic Charter, while translated, is not typically seen by the general public.

- Mention in bidding files reflected the bidding committee's perspective aiming to demonstrate strong legal protection, not necessarily widespread public awareness.

- Crucially, the court noted that newspaper articles from the relevant period often felt the need to explain what an "Olympiad" (a four-year period between Games) meant. This need for explanation, the court inferred, actually indicated that the term itself was not generally known, let alone its association specifically with the IOC as a source indicator in the minds of beverage consumers.

- The court concluded that while "OLYMPIAD" might be known among "relevant persons, experts, etc.," it did not possess the requisite level of broad public recognition among consumers of the designated goods to qualify as "well-known" for the purposes of Article 4(1)(vi). The court stated it was inappropriate to assume a high degree of fame when assessing similarity in this context.

- Similarity Assessment: Having found the fame threshold unmet, the court also briefly addressed similarity. It stated that even considering the public interest rationale of Article 4(1)(vi), the marks "OLYMBEER" and "OLYMPIAD" were clearly dissimilar in appearance, sound, and concept. Therefore, the court saw no risk of confusion or damage to the IOC's credibility.

Significance of the Decision:

The "OLYMBEER" ruling provides important clarification:

- High Bar for "Well-Known" under Art. 4(1)(vi): The decision underscores that establishing "well-known" status for this specific ground requires demonstrating broad recognition among the relevant consuming public for the goods/services in question. Niche recognition among experts or officials is insufficient. Evidence must show the mark functions as a recognized identifier in the relevant marketplace context.

- Similarity Analysis: Even for public interest marks, the assessment of similarity follows the traditional criteria of visual, phonetic, and conceptual comparison. The public interest nature of the cited mark does not automatically broaden the scope of similarity; the marks must still be genuinely confusingly similar.

Protection for Core Famous Marks like "OLYMPIC"

It is crucial to distinguish the court's finding regarding "OLYMPIAD" from the status of the core mark "OLYMPIC" (オリンピック). Unlike "OLYMPIAD," the term "OLYMPIC" is unquestionably famous and widely recognized by the general public in Japan in association with the Olympic Games and the IOC.

An application for a mark highly similar to "OLYMPIC" for related (or even unrelated) goods would face a very high likelihood of refusal in Japan. The grounds could include:

- Article 4(1)(vi): Given the fame of "OLYMPIC," it would likely meet the "well-known" threshold, and a similar mark could be refused on this basis.

- Article 4(1)(vii): Prohibits marks liable to contravene public order or morality. Using the Olympic name without authorization could potentially fall foul of this.

- Article 4(1)(xv): Prohibits marks liable to cause confusion with the goods or services of another entity. Given the fame of the Olympics, confusion regarding sponsorship or affiliation is highly likely for many goods/services.

- Article 4(1)(xix): Prohibits registration of marks identical or similar to a well-known mark in Japan or abroad, if used with unfair intentions (e.g., to free-ride on goodwill).

Furthermore, Japan, like many countries, may enact specific temporary legislation around hosting major events like the Olympics, granting enhanced protection to official names and symbols during that period. The Unfair Competition Prevention Act (不正競争防止法, Fusei Kyōsō Bōshi Hō) also offers broader protection against the misuse of famous indications that cause confusion.

Therefore, while the "OLYMBEER" decision clarified the standard for a less-recognized term like "OLYMPIAD" under Art. 4(1)(vi), it does not diminish the strong protection afforded to genuinely famous and widely recognized public interest marks like "OLYMPIC" itself under various provisions of Japanese law.

Comparison with US Trademark Law

The approach under Japanese Trademark Act Art. 4(1)(vi) has parallels and differences with US law:

- False Connection/National Symbols (Lanham Act Sec. 2(a), 2(b)): US law prohibits registration of marks that falsely suggest a connection with persons, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols (Sec. 2(a)) or consist of flags or insignia of nations or municipalities (Sec. 2(b)). This serves a somewhat similar public interest function to Japan's Art. 4(1)(vi), preventing misappropriation of institutional identity or official symbols. However, the specific tests and scope differ. Section 2(a) involves assessing whether the mark points uniquely to the institution, whether the public would assume a connection, etc.

- Fame Standard: Both systems require a mark to be well-known or famous for certain protections, but the evidentiary requirements and thresholds can vary. US law distinguishes between "famous" marks for federal dilution protection (requiring very high nationwide recognition) and "well-known" marks for broader common law protection or specific international treaty purposes. The chomei standard in Japan's Art. 4(1)(vi) appears to require broad recognition among relevant consumers but might not always equate directly to the stringent "famous" standard for US dilution.

- Olympic Marks Protection: The US provides exceptionally strong, specific protection for Olympic-related marks through the Ted Stevens Olympic and Amateur Sports Act. This act grants the US Olympic & Paralympic Committee (USOPC) exclusive rights to use "Olympic," "Olympiad," "Paralympic," the interlocking rings, and related terms commercially, largely prohibiting use by others even if there is no likelihood of confusion, subject to certain exceptions. This statutory monopoly goes beyond general trademark principles and differs from Japan's approach, which relies more on general trademark law provisions (like Art. 4(1)(vi), (xv), etc.) applied to the specific facts of recognition and potential confusion/harm.

Practical Implications for Businesses

The "OLYMBEER" case and the framework of Article 4(1)(vi) offer practical lessons:

- Trademark Clearance: When selecting and clearing trademarks for use and registration in Japan, businesses must consider not only conflicts with prior registered marks but also potential conflicts with well-known marks of public entities or public interest organizations under Art. 4(1)(vi). Avoid marks that closely mimic or could be seen as deriving from state emblems, famous international organizations, or widely recognized public bodies.

- Evidence of Fame: If relying on or challenging the "well-known" status of a public interest mark under Art. 4(1)(vi), be prepared to provide (or scrutinize) substantial evidence demonstrating (or refuting) widespread recognition among the relevant consumers of the specific goods/services at issue, not just among specialists or officials.

- Scope of Protection: Recognize that protection under Art. 4(1)(vi) is tied to the mark being genuinely well-known as an indicator of that public entity to the relevant public. Less familiar names or symbols used by such entities may not meet the threshold, as seen with "OLYMPIAD." However, core famous marks ("OLYMPIC") remain strongly protected.

- Context Matters: The assessment under Art. 4(1)(vi) involves considering the nature of the public entity, the degree of fame of its mark among relevant consumers, and the similarity between the marks.

Conclusion

Japanese trademark law provides specific mechanisms, such as Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 6, to protect the integrity and reputation associated with well-known marks of the State, public bodies, and significant public interest organizations. However, the "OLYMBEER" case demonstrates that invoking this protection requires solid proof that the cited mark is indeed "well-known" in the relevant marketplace context – specifically, among the consumers encountering the applicant's potentially similar mark. Mere recognition among experts or within official circles is insufficient. While core famous identifiers like "OLYMPIC" enjoy broad protection under various legal grounds, the status of less familiar terms associated with public interest bodies will be assessed rigorously based on evidence of public recognition. Businesses seeking to register trademarks in Japan must navigate these specific grounds for refusal alongside more standard considerations of distinctiveness and similarity, particularly when choosing marks that might evoke connections, however indirect, to established public or international symbols.

- Key Updates in Japan's 2023 Intellectual Property Law Reforms: Trademarks, Designs and Unfair Competition

- Protecting Your Brand: Navigating Personal Names in Japanese Trademark Law

- Protecting Your Intellectual Property in Japan: A Guide for US Companies

- Japan Patent Office – Trademark Examination Guidelines (English)