Protecting Confidential Information in Japanese Courts: New Measures and Established Tools

TL;DR

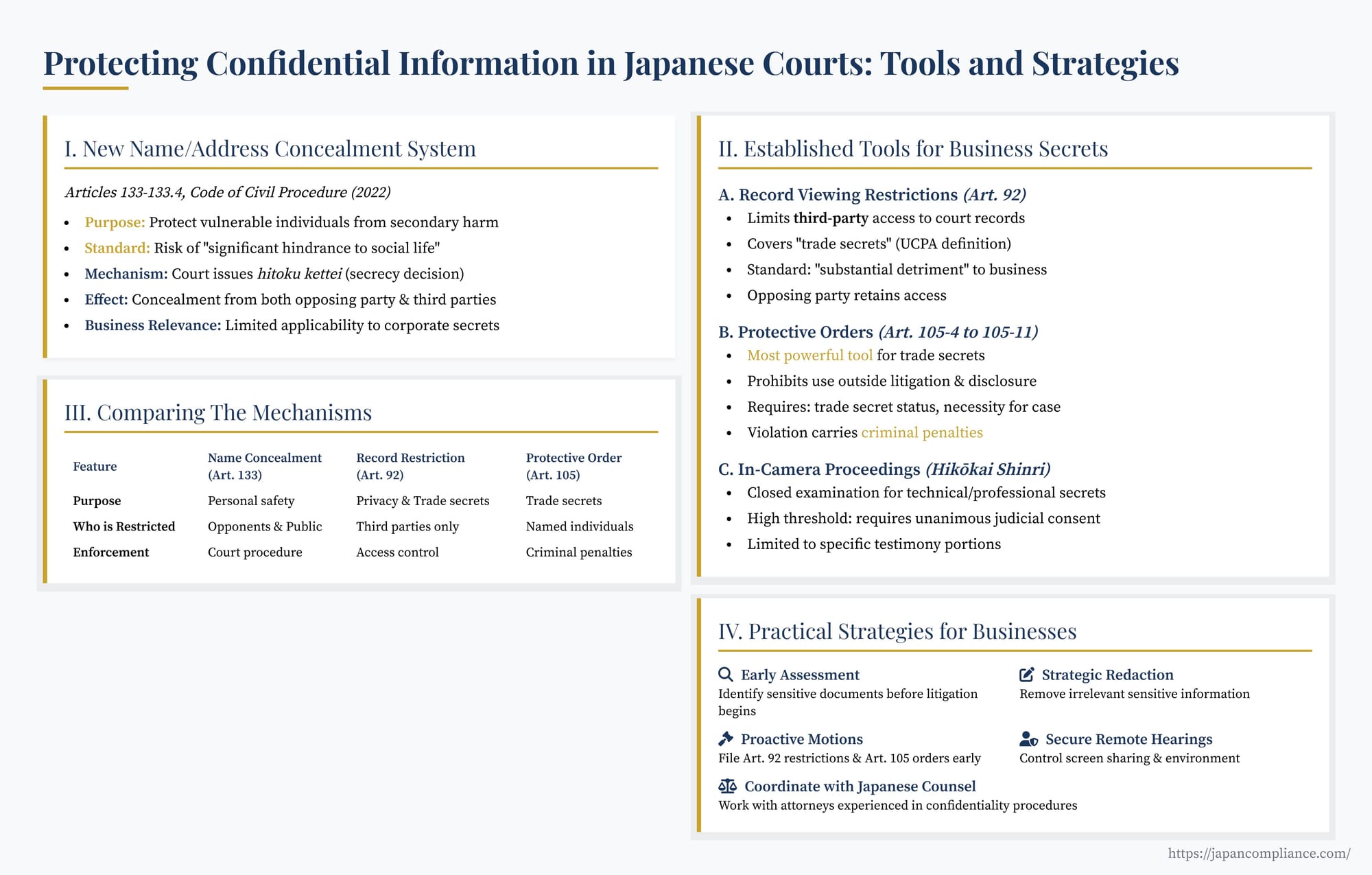

Japan’s 2022 civil-procedure amendments added a narrow name/address-concealment system, but businesses should still rely on long-standing tools—record-view restrictions (CCP Art. 92) and protective orders (CCP Arts. 105-4 ff.)—to shield trade secrets during litigation. This article compares the frameworks and offers a practical protection checklist.

Table of Contents

- The New System: Concealing Names and Addresses (CCP Arts. 133–133-4)

- Relevance of the New System for Business Information

- Protecting Business Secrets: The Established Toolkit in Japan

- Comparing the Mechanisms

- Strategies for Protecting Business Information

- Conclusion

Litigation invariably involves the exchange and exposure of sensitive information. For businesses, this can range from valuable trade secrets and proprietary technical data to confidential customer lists and internal financial records. Protecting this information from unnecessary disclosure to opposing parties, third parties, or the public is a critical concern in any jurisdiction, including Japan.

Recent amendments to Japan's Code of Civil Procedure (CCP), enacted as part of a broader digitalization effort in 2022, introduced a novel system primarily aimed at protecting the personal safety of vulnerable individuals by allowing their names and addresses to be concealed within court proceedings. While this specific mechanism has a narrow initial focus, its introduction highlights a growing awareness of confidentiality needs within the Japanese legal system.

For international businesses, however, the primary concern often lies in safeguarding competitively sensitive business information. Fortunately, beyond the new name/address concealment system, Japanese law provides established tools specifically designed for this purpose, such as restrictions on record viewing and protective orders for trade secrets. This article outlines the new name/address concealment system and then delves into the more established mechanisms available for protecting confidential business information during Japanese civil litigation, offering practical strategies for companies involved in such proceedings.

The New System: Concealing Names and Addresses (CCP Arts. 133 – 133-4)

Implemented as part of the 2022 CCP amendments, this system allows parties involved in civil litigation to request that their identifying information be kept confidential.

- Purpose and Scope: The primary legislative intent behind Articles 133 through 133-4 is the protection of individuals, particularly victims of domestic violence, stalking, or sexual offenses, from the risk of secondary harm that could arise if their whereabouts or identity became known to the opposing party (often the alleged perpetrator) or the public through court records.

- Who can apply: The system is available to any party filing a petition or other application (mōshitate-nin tō), including their legal representatives.

- Information Covered: The law allows for the concealment of:

- "Address, etc." (jūsho tō): This includes not only the person's residence but also their place of work, school, or other "usual whereabouts."

- "Name, etc." (shimei tō): This includes the person's name and any other information sufficient to identify them. The separation allows for situations where only the address needs concealment, while the name might be public, or vice-versa (though concealing the name usually implies concealing the address too).

- Mechanism – The Secrecy Decision (Hitoku Kettei):

- Motion: A party seeking protection must file a motion with the court alongside their main petition or application (Article 133(1)).

- Standard: The motion must demonstrate (somei, a prima facie showing) that if the party's address or name becomes known to the opposing party, there is a risk (osore) of causing "significant hindrance to their leading a social life" (shakai seikatsu o itonamu no ni ichijirushii shishō o shōzuru osore). This standard mirrors the language used for restricting public access to court records containing sensitive private information (Article 92(1)(i)), but its application here focuses on the risk of secondary harm or impediment to normal life resulting from disclosure to the opponent.

- Court Order: If the court grants the motion, it issues a "secrecy decision" (hitoku kettei). This decision designates alternative information (e.g., initials, a pseudonym, a lawyer's address) to be used in place of the actual name or address in the publicly accessible parts of the court record (Article 133(5)). The original, sensitive information is filed separately and kept confidential.

- Effect on Related Proceedings: Significantly, a secrecy decision generally extends automatically to related proceedings, such as counterclaims, interventions, enforcement actions, and applications for provisional remedies stemming from the main case (Article 133(5), latter part). This provides continuous protection without requiring repeated applications.

- Restricted Access to Records: Once a secrecy decision is in place, access to the portions of the court record containing the original confidential information (the "secreted part") is strictly limited. Only the party who obtained the secrecy decision can view these parts (Article 133-2(1)). Importantly, this restriction applies even to the opposing party and to third parties who might otherwise have a right to inspect court records. The restriction also covers information from which the secreted details could be inferred.

- Special Rules for Investigations: If the court needs to commission an investigation to locate a party (e.g., a defendant whose address is unknown for service of process), and that party is potentially subject to protection, the court can issue an order restricting access to the investigation report if it contains sensitive identifying information (Article 133-3).

- Challenges and Opponent Access: The system includes mechanisms to challenge or override the secrecy:

- Cancellation (Article 133-4(1)): The opposing party or an affected third party can file a motion to cancel the secrecy decision if the original requirements (risk of significant hindrance) are no longer met or were never met.

- Access for Opposing Party (Article 133-4(2)): Crucially, if the opposing party can demonstrate that being denied access to the secreted name or address information causes substantial disadvantage (jisshitsuteki na furieki) to their ability to conduct their offense or defense, they can petition the court for permission to view the otherwise restricted information. Granting such permission requires balancing the need for protection against the fundamental requirements of due process and adversarial litigation. Determining what constitutes "substantial disadvantage" will likely develop through practice; difficulty in challenging jurisdiction based on residence might be one scenario, while challenges related to identifying the correct opposing party could arise if the name is concealed.

Relevance of the New System for Business Information

While Articles 133-133.4 are clearly tailored towards protecting individuals from personal harm, could they have implications for businesses seeking to protect confidential information in litigation?

- Direct Applicability to Business Secrets: Unlikely. The core standard revolves around the "risk of significant hindrance to leading a social life." This concept is inherently personal and does not readily apply to corporations or their trade secrets. It's hard to argue that disclosing a company's trade secret hinders its "social life." Therefore, directly using Article 133 to conceal business secrets seems improbable.

- Potential Relevance for Business-Related PII: The system could be relevant in business litigation where sensitive personal information of individuals associated with the company (e.g., employees, executives, key customers involved in a dispute) is at issue, if the disclosure standard can be met for those individuals. For instance, in an employment dispute involving alleged harassment, an employee might seek to conceal their current address from the employing company if they fear retaliation impacting their personal safety or ability to live normally.

- Signaling a Trend? The introduction of this specific mechanism, alongside the digitalization facilitating easier access to records, might signal a broader judicial and legislative sensitivity towards privacy and confidentiality concerns within litigation. While not directly applicable to trade secrets, it reinforces the idea that blanket public access to all information within court files is not absolute.

Protecting Business Secrets: The Established Toolkit in Japan

For protecting competitively sensitive business information like trade secrets, technical data, customer lists, and strategic plans, Japanese law offers more established and directly applicable tools within the Code of Civil Procedure and related laws:

- Restriction on Viewing/Copying Court Records (CCP Art. 92 - Etsuran tō Seigen)

- Purpose: To limit third-party access to specific parts of the official court record. This does not generally prevent the opposing party from accessing the information.

- Scope: A party can file a motion to restrict access to portions of the record containing:

- Information causing serious harm to a party's private life if disclosed.

- Trade secrets (eigyou himitsu) held by the party.

- Definition of Trade Secret: The term "trade secret" here refers to the definition in Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (Fusei Kyōsō Bōshi Hō, UCPA), which generally requires information to be: (1) kept secret (managed as confidential), (2) useful for business activities (e.g., technical or commercial information), and (3) not publicly known.

- Standard: The court will grant the restriction if it finds that a third party accessing the information would cause "substantial detriment" (ichijirushii songai) to the party regarding their private life or their business activities based on the trade secret, and there is no overriding public interest in disclosure.

- Effect: If granted, only the parties to the litigation (and their representatives) can view or copy the restricted portions of the record.

- Protective Orders (CCP Arts. 105-4 to 105-11 - Himitsu Hoji Meirei)

- Purpose: This is a powerful tool specifically designed to protect trade secrets that must be disclosed during the litigation process (e.g., in briefs or as evidence necessary to prove a claim or defense). It prevents the receiving party from using the disclosed trade secret for any purpose other than conducting the litigation and from disclosing it to anyone not specifically authorized by the order.

- Origin: Initially introduced for patent litigation, its scope has been expanded to cover trade secrets generally in civil litigation.

- Who Can Apply: A party asserting that a trade secret they hold (or have submitted) needs protection.

- Who Can Be Bound: The order is issued against specific individuals on the opposing side, typically the party itself (if an individual), its officers/employees, legal representatives (lawyers), and potentially experts or technical advisors involved in the case.

- Conditions for Issuance (Art. 105-4(1)): The court must find that:

- The information in question (already submitted or to be submitted as evidence, or disclosed during examination) constitutes a trade secret under the UCPA.

- Disclosure of the secret is necessary for the requesting party to prove their case or for the opposing party to understand the evidence.

- Restricting the use and further disclosure of the secret is necessary to prevent the trade secret holder's business activities based on that secret from being harmed.

- Effect & Sanctions: The order specifies the scope of the trade secret, the individuals bound, and the prohibited actions (use outside litigation, disclosure to unauthorized persons). Violation of a protective order carries significant consequences, including potential criminal penalties (imprisonment or fines) under the CCP (Article 105-7 refers to Article 22 of the UCPA for penalties). This makes it a much stronger deterrent than a mere contractual confidentiality agreement.

- Access to Records Containing Secrets Under Order: If a protective order is issued concerning information in the court record, a separate motion can be made under Article 105-10 to restrict even parties not bound by the protective order from viewing those specific parts of the record, complementing the viewing restrictions under Article 92.

- In-Camera Proceedings (Hikōkai Shinri)

- While Japanese civil proceedings are generally public, Article 92(2) of the CCP allows for in-camera (closed) examination of witnesses regarding matters that constitute a party's technical or professional secret.

- This requires a motion by the party, unanimous consent of the judges, and notification to the public before the courtroom is cleared. It's a high threshold and used sparingly, typically only for the specific portion of testimony dealing directly with the secret. It does not close the entire case record.

- Practical Measures: Redaction and Confidentiality Agreements

- Redaction: Parties often proactively redact information from documents before submission if it is clearly irrelevant to the dispute but commercially sensitive or contains unrelated personal data. While useful, redaction must be justifiable, as the opposing party or the court might challenge excessive redactions that obscure relevant information.

- Confidentiality Agreements: Parties can, and often do, enter into separate confidentiality agreements (NDAs) governing information exchanged during discovery or settlement negotiations. While useful, these are contractual remedies and lack the direct enforceability and potential criminal sanctions of a court-issued protective order.

Comparing the Mechanisms

It's crucial to understand the distinct purposes and applications of these tools:

| Feature | Name/Address Concealment (Art. 133ff) | Record Viewing Restriction (Art. 92) | Protective Order (Art. 105-4ff) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Personal safety / Prevent secondary harm | Protect privacy / Business secrets from third parties | Protect trade secrets disclosed in litigation |

| Information Covered | Name, Address, Other Identifiers | Private life matters, Trade Secrets | Trade Secrets (UCPA definition) |

| Who is Restricted? | Opposing party & Third Parties (initially) | Third Parties | Specific individuals on opposing side named in order |

| Trigger Standard | Risk of "Significant hindrance to social life" | "Substantial detriment" to privacy / business | Necessity for litigation & Prevention of business harm |

| Key Effect | Concealment in public record / Restricted viewing | Restricted viewing/copying by third parties | Prohibition on use outside litigation & disclosure |

| Main Applicability | Primarily individuals (DV, stalking victims, etc.) | Individuals (privacy), Businesses (trade secrets) | Businesses (trade secrets needed for case) |

| Opponent Access Possible? | Yes, upon showing "substantial disadvantage" | Yes (as a party) | Yes (but bound by the order's restrictions) |

The new name/address concealment system (Art. 133ff) primarily prevents initial disclosure to the opponent and public, focusing on personal safety. Restrictions on viewing (Art. 92) prevent third parties from accessing sensitive parts of the record. Protective Orders (Art. 105-4ff) address the situation after a trade secret has been disclosed to the opponent for litigation purposes, preventing its misuse.

Strategies for Protecting Business Information

Companies facing litigation in Japan should proactively consider how to protect their confidential information:

- Early Information Assessment: As soon as litigation is anticipated, identify potentially sensitive documents and data – trade secrets, confidential financial information, sensitive PII – that might need to be produced or referenced.

- Strategic Redaction: Before submitting documents, carefully redact information that is clearly irrelevant to the legal issues but commercially sensitive. Be prepared to justify redactions if challenged.

- Motion for Restriction on Viewing (Art. 92): If documents containing trade secrets or sensitive private information must be filed with the court, consider filing a motion under Article 92 to restrict third-party access concurrently.

- Motion for Protective Order (Art. 105-4): If trade secrets must be disclosed to the opposing party (e.g., as key evidence), apply for a protective order before or at the time of disclosure. Clearly define the scope of the secret and the individuals to be bound. This is the strongest tool for preventing misuse of disclosed secrets.

- Careful Disclosure in Remote Hearings: Be mindful of screen sharing during web conferences. Ensure only necessary information is displayed and that the environment prevents unauthorized viewing.

- Coordinate with Counsel: Work closely with Japanese legal counsel who are experienced with these procedures. Ensure they understand which information is considered highly confidential and strategize early on the best methods for protection.

- Internal Protocols: Ensure internal teams involved in gathering information for litigation understand the importance of confidentiality and follow secure data handling procedures.

Conclusion

Japan's recent introduction of a system for concealing names and addresses in civil litigation marks an important step in protecting vulnerable individuals. While its direct application to safeguarding corporate trade secrets is limited due to its specific standard and purpose, its existence reflects a heightened awareness of privacy and confidentiality concerns within the increasingly digitalized court system.

For international businesses, the key takeaway is that Japan offers a distinct, albeit different from the US, toolkit for protecting sensitive information in court. The established mechanisms – particularly Protective Orders under Article 105-4 et seq. for trade secrets disclosed during the case, and Restrictions on Viewing under Article 92 for limiting third-party access to filed secrets – remain the primary vehicles for safeguarding confidential business data. Successfully protecting sensitive information requires a proactive approach: understanding the different tools available, identifying confidential information early, strategically employing redaction and court motions, and working closely with experienced Japanese counsel to navigate the specific procedures and standards.

- Navigating the Maze: Jurisdiction and Governing Law in Cross-Border Trade Secret Disputes Involving Japan

- Trade Secret Litigation in Japan: Understanding Proof and Damages

- Judging in the Dark? Japan's Supreme Court Rejects In Camera Review for Undisclosed Government Documents

- Overview of the 2022 Code of Civil Procedure Amendments — Ministry of Justice