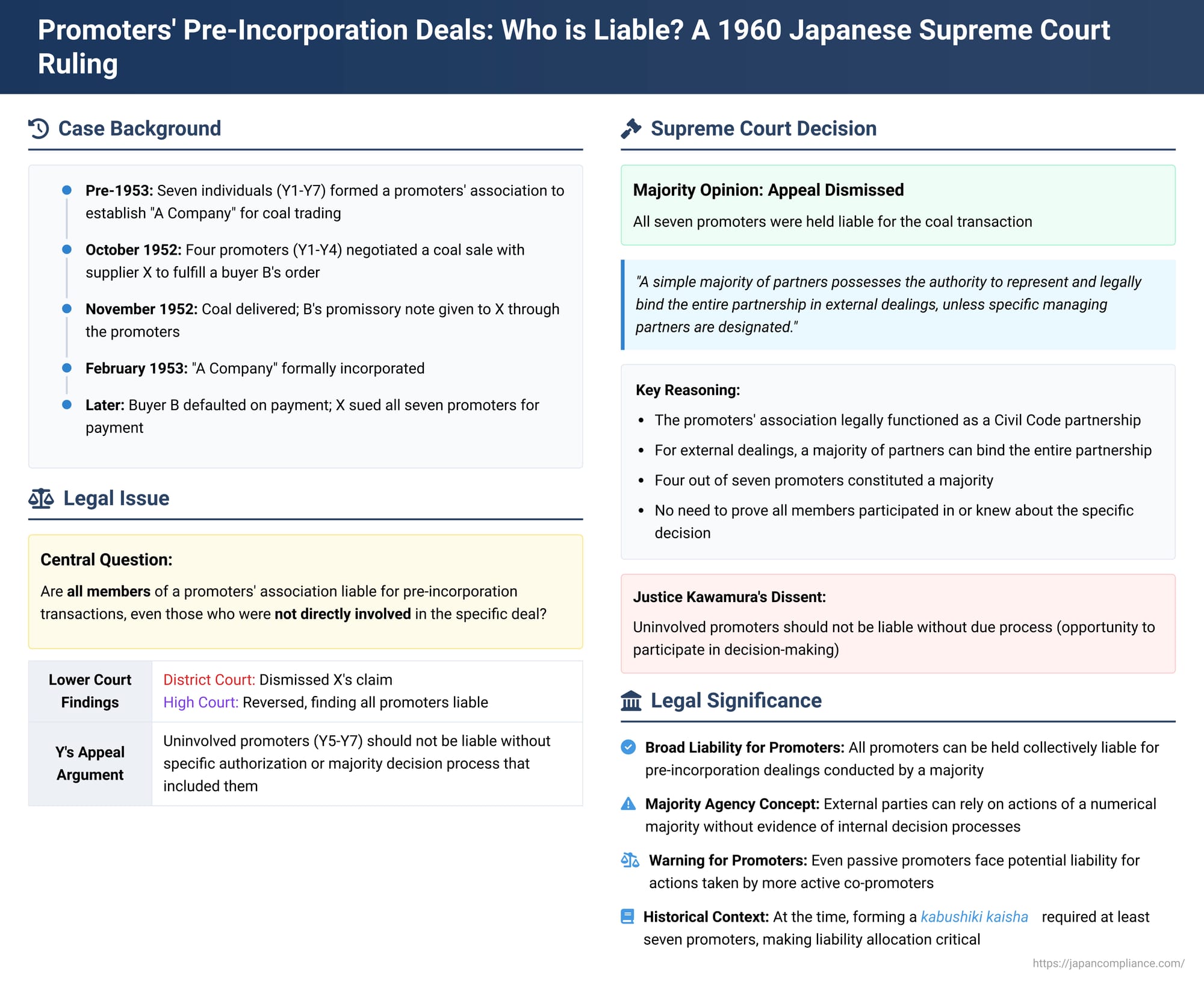

Promoters' Pre-Incorporation Deals: Who is Liable? A 1960 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on "Promoters' Associations"

Judgment Date: December 9, 1960

Before a company is formally incorporated, its founders, known as promoters (発起人 - hokkinin), often engage in various activities to lay the groundwork for the new enterprise. These activities can range from purely preparatory acts, like drafting the articles of incorporation, to conducting actual business transactions under the prospective company's name. When these pre-incorporation business dealings lead to liabilities, a critical question arises: are all promoters collectively responsible, even those who were not directly involved in a specific transaction? A 1960 Supreme Court of Japan decision delved into this issue, clarifying the scope of liability for members of a "promoters' association" (発起人組合 - hokkinin kumiai), which is legally treated as a form of partnership in Japan.

The Coal Deal Before Company Formation

The case involved a group of seven individuals, Y et al., who were the promoters for a new company, to be named "A Company" (A), intended to engage in the business of selling coal and other goods. At least five of these promoters (Y1 to Y5) had already been conducting coal trading business using the name "A" even before the company was formally incorporated on February 16, 1953.

In October 1952, while A Company was still in its pre-incorporation phase, the promoters' group, operating under the name "A," received an inquiry for a coal order from a purchaser, B, through a broker, C. The promoters' group then approached X, a coal supplier with whom they had previous dealings, to fulfill this order. An agreement was reached: X would deliver the coal to B, and in return, the "A" promoters' group would arrange for X to receive a promissory note issued by B, payable to X.

The coal was duly delivered to B by November 1, 1952, and B's promissory note, made out to X, was handed over to the Y promoters. On November 4, X received this promissory note from the Y promoters. It was noted that during this period, employees of X had visited B for investigation and to witness aspects of the transaction. Furthermore, only four of the seven Y promoters (Y1 to Y4) had been directly involved in the negotiations with X.

Unfortunately, B, the ultimate purchaser, defaulted on the promissory note. Consequently, X, the coal supplier, sued all seven promoters (Y et al.) for payment of the outstanding amount.

The Legal Dispute: Liability of Uninvolved Promoters

The primary legal battle, up to the High Court, centered on whether "A" – either as the yet-to-be-formed company or as the promoters' association acting under that name – was the actual contracting party, and by extension, which of the promoters were liable. The Tokyo District Court initially dismissed X's claim. However, the Tokyo High Court reversed this, finding in favor of X. The High Court held that the coal sale was a commercial act conducted "for the benefit of all of Y et al. who conducted the coal selling business under the name of A," thus making all seven promoters liable.

Y et al. appealed to the Supreme Court. Their main contention, particularly for promoters Y5, Y6, and Y7 who were not directly involved in the transaction with X, was that pre-incorporation business activities not strictly essential for the company's formation (such as this specific coal sale) should not automatically create liability for them. They argued that their liability could only be established if there was evidence of their specific authorization for this transaction, or proof that they had formed a distinct partnership for coal trading with delegated authority, or that the transaction was approved by a majority decision of the promoters in which they had a chance to participate.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Majority Rule for Agency

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated December 9, 1960, dismissed the appeal by Y et al., thereby upholding the liability of all seven promoters.

The majority opinion reasoned as follows:

- Nature of the Promoters' Activities: The Court first interpreted the High Court's findings to mean that Y et al. had formed a "promoters' association" (hokkinin kumiai) with the primary objective of establishing company A. However, this association also engaged in the separate business of coal trading – an activity not inherently part of its "original purpose" of company formation – under the "A" name, and the transaction with X was part of this ongoing coal business.

- Promoters' Association as a Civil Code Partnership: Such a promoters' association is legally regarded as a partnership (kumiai) under the Japanese Civil Code.

- Liability of All Partners: The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's conclusion that the legal effects of the coal sale contract accrued to all seven members of this promoters' association (Y et al.).

- Majority Agency in Partnerships: The Court's crucial reasoning for this collective liability was based on its interpretation of agency in partnerships: Unless a partnership agreement or other internal rules specifically designate certain partners as "managing partners" (業務執行組合員 - gyōmu shikkō kumiaiin) with exclusive authority to act for the partnership, then for the purpose of external dealings, a simple majority of the partners possesses the authority to represent and legally bind the entire partnership.

Therefore, even if only a subset (in this case, four of the seven) of the promoters directly negotiated and concluded the transaction with X, their actions, if representing a majority, were deemed to bind all members of the promoters' association, including those not directly involved in that specific deal.

The Dissenting View: Concerns about Fairness and Due Process

Justice Daisuke Kawamura issued a strong dissenting opinion, highlighting several concerns with the majority's reasoning:

- Factual Clarity and Reasons for Judgment: The dissent first questioned whether the High Court had clearly established that all seven promoters were directly involved or if it simply imputed liability. If the latter, the High Court had failed to adequately explain its reasons for extending liability to the uninvolved promoters.

- Distinction Between Internal Business Execution and External Agency: Justice Kawamura emphasized the need to distinguish between how a partnership internally decides to execute its business and how it is represented in dealings with third parties.

- If specific managing partners are appointed, they would typically have the authority to represent the partnership in transactions related to the business they are authorized to execute.

- If no specific managing partners are designated, then for matters that are not part of the partnership's ordinary business, a decision to engage in a specific transaction (and to delegate authority to certain partners to act as agents for that transaction) should be made by a majority of the partners, as per Article 670, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code (which governs internal business execution).

- Meaning of "Majority Decision": Crucially, the dissent argued that a "majority decision" under Article 670 implies that all partners must be given an opportunity to participate in the deliberation and decision-making process. It is not sufficient for a mere numerical majority of partners to make a decision without affording the minority an opportunity to express their views or to even be aware of the proposed action.

- Unfairness of Imputed Liability without Due Process: Justice Kawamura contended that the majority opinion's leap to a principle of "majority agency" for external acts, without first ensuring that an internal majority decision (with due process for all members) had occurred, was problematic. He argued that it was unacceptable for uninvolved partners to be held liable for actions taken by a segment of the group if those uninvolved partners had no knowledge of the proposed transaction and thus no opportunity to prevent it (for example, by voicing objections or even choosing to withdraw from the promoters' association if they disagreed with the course of action).

Unpacking the Legal Concepts

This case touches upon several key legal concepts in Japanese partnership and company law:

- Promoters' Association (Hokkinin Kumiai): This is not a formally registered legal entity itself but rather a contractual relationship among individuals who come together for the purpose of establishing a company. Legally, it is treated as a partnership under the Civil Code. Its primary purpose is to carry out the acts necessary for incorporation.

- Partnership Agency under the Civil Code: The Civil Code provides that the execution of a partnership's ordinary business may be decided by a majority of its members (unless otherwise stipulated). However, the rules for external representation (agency) are less explicit if no specific managing partners are appointed. This case highlights the differing judicial interpretations – the majority favoring a broad "majority agency" for external acts, while the dissent argued for a closer link to internal decision-making processes that respect the participatory rights of all partners.

- Preparatory Acts vs. Business Activities: There's a distinction between acts that are purely preparatory to forming a company (e.g., drafting articles, securing initial capital commitments) and engaging in the actual business that the future company intends to conduct. In this case, the promoters' association was found to be doing the latter – actively trading coal – even before the company was formally established.

Analysis and Implications

The 1960 Supreme Court decision in this matter has several important implications:

- Broad Liability for Promoters: The majority ruling established a precedent for holding all members of a promoters' association liable for business transactions conducted by a majority of its members in the association's name prior to formal incorporation, even if not all promoters were directly involved in or aware of every specific transaction. This underscores the collective nature of liability within such pre-incorporation partnerships.

- Critique of the "Majority Agency" Rule: The main criticism, well-articulated in Justice Kawamura's dissent and echoed by legal commentators, is that the majority's concept of "majority agency" for external acts might not adequately protect the rights of minority or less active promoters. If a numerical majority can bind the entire group without a formal internal decision-making process that includes all members, it could lead to unfair outcomes for those kept out of the loop.

- Practical Considerations for Promoters: This case serves as a significant caution for individuals considering becoming promoters of a company. It highlights the potential for broad, joint liability arising from the pre-incorporation activities undertaken by the group, even if one is not actively involved in every decision or transaction. Clear internal agreements within the promoters' association regarding authority, decision-making, and scope of pre-incorporation activities become crucial.

- Historical Context (Number of Promoters): As the PDF commentary notes, at the time of this ruling and until a 1990 Commercial Code amendment, the establishment of a kabushiki kaisha (stock company) required at least seven promoters. This historical requirement might have influenced judicial thinking about the expected roles and potential liabilities of a larger group of promoters, some of whom might inevitably be less active than others in day-to-day pre-incorporation dealings.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1960 decision confirmed that a promoters' association, acting as a Civil Code partnership, can be bound by the business dealings undertaken by a majority of its members in the association's name, even before the intended company is formally incorporated. This means all promoters, including those not directly participating in a specific transaction, can be held liable for obligations arising from such dealings. While this ruling provides a degree of certainty for third parties transacting with promoters' groups, the strong dissenting opinion and subsequent academic critique have highlighted ongoing concerns about ensuring fairness and proper internal governance within such associations to protect the interests of all their members. The case underscores the significant responsibilities and potential liabilities that individuals assume when they embark on the collective endeavor of promoting a new company.