Promises Before Birth: Promoter Liability for Pre-Incorporation Contracts in Japan

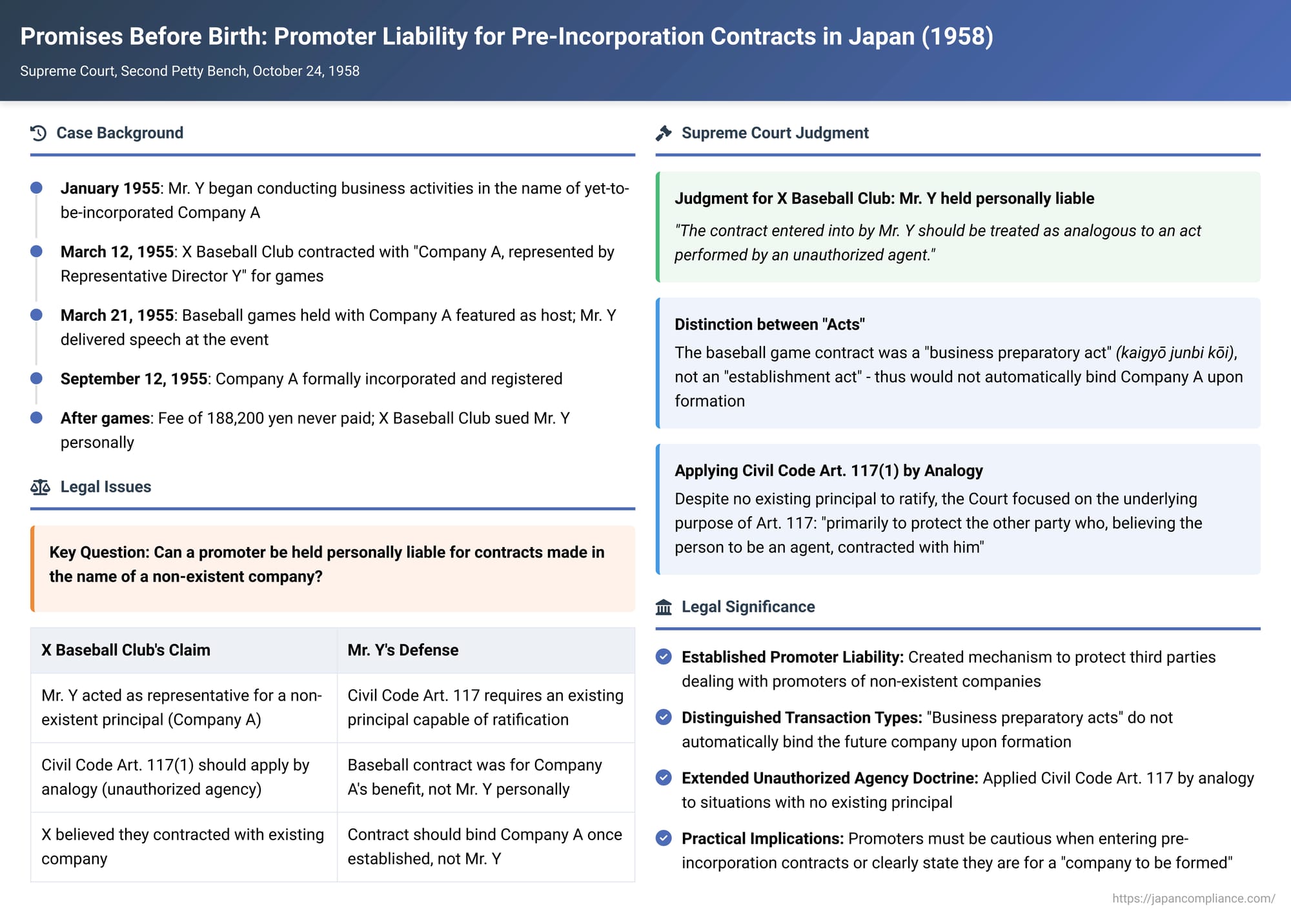

The period leading up to a company's formal incorporation is often bustling with activity. Promoters, the individuals orchestrating the company's formation, may enter into various contracts to secure assets, arrange services, or even generate initial publicity for the nascent enterprise. But what happens if these "pre-incorporation contracts," particularly those aimed at preparing for future business operations rather than the act of incorporation itself, are made in the name of a company that doesn't legally exist yet? Who is liable if things go wrong? A Japanese Supreme Court decision on October 24, 1958, provided crucial guidance on these questions, particularly concerning the personal liability of promoters for such "business preparatory acts."

The Facts: A Baseball Game for a Company-To-Be

The case involved Mr. Y and a Mr. B, who were in the process of promoting the establishment of Company A, a joint-stock company intended to engage in textile finishing, sales, and related businesses. Even before Company A was formally incorporated and registered (which eventually occurred on September 12, 1955), Mr. Y had been conducting business activities in Company A's name since around January 1955, presenting himself as its representative director.

Mr. B conceived a plan to organize baseball games hosted by the yet-to-be-formed Company A, believing it would serve as good publicity for the future company. Mr. Y agreed with this promotional strategy and entrusted Mr. B with the task of negotiating a contract with X Baseball Club (a professional team then known as the Daiei Stars). These negotiations were to be conducted in the name of Company A.

X Baseball Club, believing that Company A was already an existing legal entity and that Mr. Y was its duly authorized representative director, entered into a contract on March 12, 1955. The contract was formally with "Company A, represented by Representative Director Y," and pertained to the execution of baseball games. The games were subsequently held on March 21, 1955, between X Baseball Club and another team. Advertisements and posters for the event prominently featured Company A as the host, and Mr. Y even delivered a speech at the event representing the organizing entity. It was clear that Mr. Y was fully aware of all the circumstances surrounding the contract.

However, the agreed-upon appearance fee and expenses, totaling 188,200 yen, were never paid to X Baseball Club. Consequently, X Baseball Club filed a lawsuit, not against the (by then incorporated) Company A, but against Mr. Y personally. The plaintiff argued that Mr. Y had entered into the contract in the capacity of a representative of a principal (Company A) that did not legally exist at the time of the contract. X Baseball Club asserted that this situation was analogous to a case of unauthorized agency and sought payment from Mr. Y based on an analogy to Article 117, Paragraph 1 of the Japanese Civil Code (which deals with the liability of a person who contracts as an agent for another without having authority to do so).

Lower Courts: Finding a Basis for Promoter Liability

The first instance court found in favor of X Baseball Club, holding Mr. Y personally liable. Mr. Y appealed, but the Tokyo High Court affirmed the lower court's decision. The High Court's reasoning was pivotal:

- It acknowledged the general legal principle that rights and obligations arising from acts performed by promoters, acting as executive organs of a company-in-formation and within the scope of their authority, would typically vest in the company once it is successfully established.

- However, the High Court strictly defined the scope of this authority, limiting it to acts that are "necessary for establishing the company."

- The contract for the baseball games, even if intended for promotional purposes to benefit the future business of Company A, was classified as a "business preparatory act" (開業準備行為 - kaigyō junbi kōi). Such an act, the court held, was "by no means to be considered an act necessary for company establishment."

- The High Court found that X Baseball Club genuinely believed Company A existed at the time of the contract and that Mr. Y was its authorized representative, and further, that X Baseball Club was not negligent in holding this belief.

- Since Company A did not legally exist at the moment of contracting, there was no "principal" for Mr. Y to represent. While this meant Mr. Y was not strictly an "unauthorized agent" in the literal sense of Civil Code Article 117 (which usually presumes an existing principal), the High Court found the situation to be closely analogous. Therefore, it concluded that the "legal intent" (法意 - hōi) of Article 117, Paragraph 1 should be applied by analogy, making Mr. Y personally liable to X Baseball Club, at the latter's choice, for either performance of the contract or damages.

Mr. Y appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other things, that Civil Code Article 117(1) presupposes the existence of a principal who is capable of ratifying the agent's act, a condition not met here since Company A did not exist at the time of the contract.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation and Reasoning

The Supreme Court, in its Second Petty Bench judgment of October 24, 1958, dismissed Mr. Y's appeal and upheld the High Court's decision. The Court's concise reasoning solidified an important aspect of Japanese company law concerning pre-incorporation activities.

- "Business Preparatory Acts" vs. "Establishment Acts": The Supreme Court concurred with the High Court that the contract for the baseball game could not be considered an act "concerning the establishment of the company" (kaisha no setsuritsu ni kansuru kōi).

- No Automatic Devolution to the Company: Because the contract was not an "establishment act," its legal effects (rights and obligations) would not automatically devolve upon or bind Company A after its formal incorporation.

- Analogy to Unauthorized Agency (Civil Code Article 117(1)):

- The Court stated that, consequently, the contract entered into by Mr. Y should be treated as "analogous to an act performed by an unauthorized agent."

- It acknowledged Mr. Y's argument that Civil Code Article 117 was originally designed for situations where someone acts as an agent for an existing person without authority, and that Mr. Y, having contracted as a representative of a non-existent company, was not, in a strict sense, an unauthorized agent.

- However, the Supreme Court emphasized the underlying purpose of Article 117: "primarily to protect the other party who, believing the person to be an agent, contracted with him."

- Given this protective purpose, the Court concluded that in a "similar relationship" like the one in the present case, Article 117 should be applied by analogy. Therefore, Mr. Y, who contracted as the representative of the then-non-existent Company A, should bear responsibility.

Understanding "Business Preparatory Acts" (Kaigyō Junbi Kōi)

The concept of "business preparatory acts" (kaigyō junbi kōi) is central to this case.

- Generally, these are defined as transactional acts undertaken by promoters to prepare the necessary human or material resources for the company's business operations after it is formally established. The contract to hold promotional baseball games clearly falls into this category.

- The rule established by this Supreme Court case is that such acts, because they are not strictly for the purpose of bringing the company into legal existence, do not automatically bind the company once it is formed. This principle has been followed in subsequent case law.

- It's important to distinguish these from acts that are directly part of the incorporation process (e.g., preparing articles of incorporation, securing initial capital subscriptions). There's also a special category under Japanese company law known as zaisan hikiuke (property acquisition by the company from a promoter or third party, agreed upon before incorporation). For zaisan hikiuke to be binding on the newly formed company, strict procedural requirements must be met, including specification in the articles of incorporation and, typically, an investigation by a court-appointed inspector. These requirements are designed to protect the company's initial capital. Business preparatory acts, like the one in this case, which do not meet such stringent criteria, generally fall outside the scope of what promoters can validly do on behalf of the future company.

The Scope of Promoters' Authority

This case touches upon the broader question of the scope of a promoter's authority when acting for a company that is still in the process of formation (a "company-in-formation" or 設立中の会社 - setsuritsū no kaisha).

- Japanese legal theory often employs the "identity theory" (dōitsusei setsu), which views the company-in-formation as a de facto association or an embryonic form of the future company. Under this theory, acts performed by promoters acting as the executive organs of this company-in-formation, provided they are within the scope of their legitimate authority, can become the rights and obligations of the formally incorporated company without needing a special transfer process.

- The crucial issue then becomes: what is the extent of this "legitimate authority"?

- One restrictive view limits this authority strictly to acts aimed directly at the formation and establishment of the company itself (e.g., legal procedures for incorporation).

- A slightly broader view might include acts that are factually or economically necessary for the establishment process.

- However, both these traditional views generally agree that "business preparatory acts"—those aimed at future operations rather than formation—fall outside the promoters' authority to bind the future company, unless they qualify under the stringent rules for zaisan hikiuke. The Supreme Court's decision in this case aligns with this by stating that the baseball contract was not an "act concerning the establishment of the company."

- Some legal scholars have argued for a somewhat broader scope of authority for promoters, suggesting it should extend to necessary business preparatory acts, as the ultimate goal of formation is to create an operational entity. However, they also propose that such extended authority should be subject to safeguards to prevent abuse and protect the company's financial foundation, perhaps by analogously applying the strict requirements for zaisan hikiuke (e.g., disclosure in articles of incorporation, objective valuation where possible).

Rationale for Promoter Liability and Third-Party Protection

The Supreme Court's decision to hold Mr. Y personally liable by analogy to Civil Code Article 117(1) is rooted in the need to protect third parties.

- When a person (the promoter) contracts as if representing an existing company, and the third party relies on this representation, the law seeks to provide a remedy if it turns out the "principal" (the company) did not exist or the "agent" (the promoter) lacked authority to bind it.

- The argument that Article 117(1) strictly applies only when there is an existing principal capable of ratifying the act was acknowledged but overcome by focusing on the article's protective purpose for the third party. Japanese courts have, in other contexts as well, applied Article 117 by analogy where a principal was non-existent or lacked legal capacity.

- The Court implicitly found that Mr. Y had created the appearance that Company A was an existing, operational entity with him as its representative. X Baseball Club relied on this appearance. The commentary notes that in such situations, where the promoter acts as if the company is already established, affirming promoter liability protects the third party's trust. This is distinguished from situations where a promoter explicitly contracts on behalf of a company to be formed, making it clear to the third party that the company does not yet exist. In those latter cases, the third party is aware of the promoter's current lack of authority to bind a non-existent principal, and the promoter might not be held liable under Civil Code Article 117(2) (which provides exceptions to liability if the third party knew or should have known of the lack of authority, or if the agent lacked authority due to their own lack of legal capacity).

- The commentary also supports the High Court's finding that X Baseball Club was not negligent in believing Company A existed, especially since Mr. Y was already conducting business activities in Company A's name before its formal registration. Therefore, the failure of X Baseball Club to verify Company A's existence through the corporate registry did not absolve Mr. Y of liability.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1958 judgment in this case involving pre-incorporation business preparatory acts remains a significant decision in Japanese company law. It clarified that such acts, undertaken by promoters before a company is formally established, generally do not automatically bind the subsequently formed company unless they meet very specific legal requirements (like those for zaisan hikiuke). More importantly, the decision established a vital mechanism for protecting third parties who deal with promoters acting in the name of a non-existent company. By applying the principles of unauthorized agency liability (Civil Code Article 117(1)) by analogy, the Court affirmed that promoters who create the appearance of representing an existing entity can be held personally responsible for the obligations arising from such pre-incorporation contracts. This underscores the importance of clarity and caution for promoters when entering into commitments before their company achieves legal personality, and provides a pathway for redress for third parties who might otherwise be left without a remedy.