Privatization Pitfall: Japanese Supreme Court Rules City's Rejection Notice to Operator Candidate Not an "Administrative Disposition"

Date of Judgment: June 14, 2011

Case Number: Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, 2010 (Gyo-Hi) No. 124

Introduction

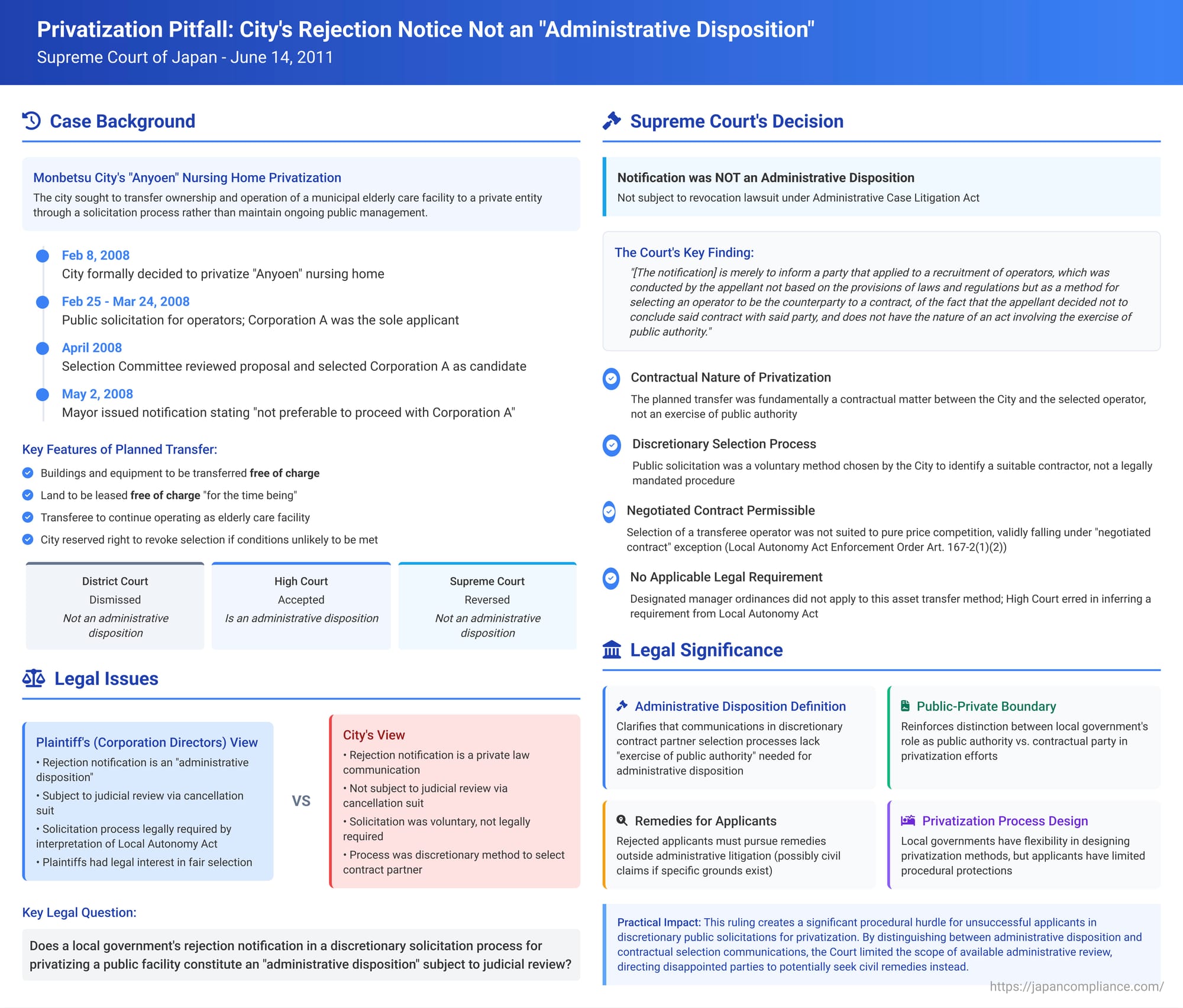

On June 14, 2011, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a judgment clarifying the legal nature of a notification issued by a city to an unsuccessful applicant in a public solicitation process for the privatization of a municipally-owned elderly care facility. The core issue was whether this notification—informing the applicant that a final decision to select them had not been reached—constituted an "administrative disposition" (gyōsei shobun) subject to a lawsuit for cancellation under administrative litigation procedures. The Court's decision to overturn the High Court and find that the notification was not an administrative disposition provides important guidance on the demarcation between administrative acts reviewable by courts and preparatory actions related to contractual matters by local governments.

The case involved prospective directors of a social welfare corporation who had applied to take over the operation of a nursing home in Monbetsu City. After being initially selected as a candidate, they received a notice from the Mayor effectively rejecting their bid. They challenged this notice, seeking its revocation.

Factual Background

The dispute arose from Monbetsu City's efforts to transfer a municipally-owned and operated elderly care facility to a private operator.

1. Monbetsu City's Privatization Plan for "Anyoen Nursing Home"

On February 8, 2008, Monbetsu City (hereinafter "the City") formally decided to privatize its elderly care facility, the Monbetsu Municipal Anyoen Nursing Home (hereinafter "Anyoen" or "the facility"). The City's objective was to ensure the long-term, stable operation of the facility by a single private entity. To achieve this, the City opted for an "asset transfer method" (施設譲渡方式 – shisetsu jōto hōshiki), where the facility's assets would be transferred to the chosen operator. This was preferred over a "designated manager system" (指定管理者方式 – shitei kanrisha hōshiki), under which a private operator manages a public facility for a fixed period while the local government retains ownership.

To select the private entity that would take over the facility's assets and operations (hereinafter "the Transferee Operator"), the City decided to conduct a public solicitation for proposals. It established the "Monbetsu Municipal Anyoen Privatization Transferee Operator Candidate Recruitment Guidelines" (hereinafter "the Recruitment Guidelines") to govern this process.

Key terms outlined in the Recruitment Guidelines included:

- The City would transfer the buildings and equipment of Anyoen (hereinafter "the Facility Assets") to the selected Transferee Operator free of charge.

- The land on which Anyoen was situated (hereinafter "the Land") would be leased to the Transferee Operator free of charge "for the time being."

- The Transferee Operator would be obligated to operate Anyoen as an elderly care facility in accordance with specific transfer conditions and to faithfully perform all terms of the contract to be concluded with the City.

- The City reserved the right to revoke its selection of a Transferee Operator, even after an initial decision, if it determined that the transfer conditions were unlikely to be met.

2. The Solicitation Process and Corporation A's Application

The City conducted the public solicitation for Transferee Operators from February 25, 2008, to March 24, 2008 (hereinafter "the Solicitation"). A social welfare corporation in the process of being established, known as "Corporation A," submitted a proposal on March 24, 2008. Corporation A was the sole applicant.

Following the application period, the "Transferee Operator Candidate Selection Committee," established by the City, reviewed Corporation A's proposal and conducted hearings with its prospective directors. The Selection Committee subsequently selected Corporation A as a candidate for becoming the Transferee Operator.

3. The Mayor's Notification of Non-Decision

Despite the Selection Committee's recommendation, on May 2, 2008, the Mayor of Monbetsu issued a formal notification to Corporation A (hereinafter "the Notification"). The Notification stated that, after consideration, the City had "judged it not preferable to proceed with the privatization procedures with Corporation A as the counterparty." Therefore, the Notification concluded, "a decision regarding [Corporation A's] proposal had not been reached." This effectively amounted to a rejection of Corporation A's bid.

Procedural History

The prospective directors of Corporation A (hereinafter "P" or "the Plaintiffs") challenged the Mayor's Notification.

- Lawsuit Filed: P filed an administrative lawsuit seeking, among other things, the cancellation (torikeshi) of the Notification, arguing that it was an illegal administrative disposition.

- First Instance Court (Asahikawa District Court): The District Court dismissed P's claim for cancellation. It reasoned that the planned transfer of Anyoen was essentially a matter of private law contract between the City and the chosen operator. Therefore, the Notification, being a communication related to the non-conclusion of such a contract, did not qualify as an administrative disposition subject to review in an administrative lawsuit.

- High Court (Sapporo High Court): P appealed to the Sapporo High Court, which reversed the District Court's decision. The High Court found that the Notification did constitute an administrative disposition. It reasoned that since Monbetsu City's own ordinances generally required a public solicitation process for selecting designated managers of public facilities (a system the City had considered but ultimately decided against for Anyoen), and given that an outright asset transfer was a more significant step, it could be inferred that a public solicitation process was also required by interpretation of the Local Autonomy Act for this "facility transfer method." Consequently, the High Court held that applicants like Corporation A had a legal interest in a fair and proper selection process conducted according to the Recruitment Guidelines, and that the Notification infringed upon this interest. The High Court therefore granted P's request and cancelled the Notification. (It dismissed P's separate claim for an order obligating the City to issue a notice of selection).

The City then appealed the High Court's ruling on the cancellation of the Notification to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision and Reasoning

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision regarding the cancellation of the Notification, ultimately agreeing with the first-instance court that the Notification was not an administrative disposition.

Main Decision:

- The part of the High Court judgment that had ruled in favor of P (cancelling the Notification) was quashed (reversed).

- The High Court appeal by P (against the first-instance judgment) was dismissed with respect to that part. (This effectively reinstated the District Court's dismissal of P's suit for cancellation).

- Litigation costs for both the High Court appeal and the Supreme Court appeal were ordered to be borne by P.

Core Reasoning: The Notification Was Not an Administrative Disposition

The Supreme Court's central reasoning was as follows:

- Nature of the Privatization Plan as a Contract: The Court first established that the intended method for the privatization of Anyoen was the conclusion of a contract ("the Contract") between the City and the selected Transferee Operator. This contract would involve the City transferring the Facility Assets (buildings and equipment) free of charge and leasing the Land free of charge, in return for the Transferee Operator committing to operate the facility as an elderly care home under specified conditions.

- Contractual Nature Unchanged by Reserved Rights: The Recruitment Guidelines included a clause allowing the City to revoke its selection of an operator if it deemed that the transfer conditions were unlikely to be fulfilled. The final Contract would likely contain similar clauses, such as rights for the City to terminate the land lease for public interest reasons (as permitted under Article 238-5, Paragraph 4, and Article 238-4, Paragraph 5 of the Local Autonomy Act) or to terminate both the lease and the asset transfer agreement for violations of use restrictions (as per Article 238-5, Paragraphs 6 and 7 of the Local Autonomy Act). However, the Supreme Court noted that the decision to enter into such a contract ultimately rests on the mutual consent of both parties. These reserved rights for the City, while significant, do not fundamentally alter the essential character of the intended transaction as a contract.

- Permissibility of Negotiated Contract: The Court observed that the selection of a Transferee Operator for Anyoen was not a matter that could be determined solely by comparing bid prices. The nature of the services and the long-term operational responsibilities involved qualitative assessments. Therefore, the Contract fell under the category of "other contracts whose nature or purpose is not suited to competitive bidding," as described in Article 167-2, Paragraph 1, Item 2 of the Local Autonomy Act Enforcement Order. This provision allows local governments to conclude such contracts through a negotiated process (zuii keiyaku) rather than being strictly bound by competitive bidding rules.

- Inapplicability of Designated Manager Ordinances: The Monbetsu City ordinances concerning the procedures for appointing "designated managers" for public facilities (under Article 244-2, Paragraph 3 of the Local Autonomy Act) were specific to that particular system of public facility management. They did not apply to the conclusion of the asset transfer Contract envisaged in the Anyoen privatization plan.

- Solicitation Process Was Discretionary, Not Legally Mandated: Based on the above points, the Supreme Court concluded that the public solicitation process (the Solicitation) undertaken by the City was not based on any specific legal requirement compelling such a process for this type of asset transfer. Instead, it was a method voluntarily chosen by the City as a means to identify and select a suitable private operator to be its contractual counterparty for the privatization of Anyoen.

- Nature of the Notification: Given that the Solicitation was a discretionary, non-legally mandated procedure for selecting a contract partner, the Mayor's Notification to Corporation A was merely a communication informing an applicant of the City's internal decision not to proceed to conclude a contract with that applicant.

The Court held that such a notification, in this context, "is merely to inform a party that applied to a recruitment of operators, which was conducted by the appellant not based on the provisions of laws and regulations but as a method for selecting an operator to be the counterparty to a contract, of the fact that the appellant decided not to conclude said contract with said party, and does not have the nature of an act involving the exercise of public authority." - Conclusion: Not an Administrative Disposition: Therefore, the Notification did not constitute an "administrative disposition" (gyōsei shobun) that could be the subject of a lawsuit for cancellation (kōkoku soshō). The Court cited its own precedents (Supreme Court, July 12, 1960, Minshu Vol. 14, No. 9, p. 1744; Supreme Court, Grand Bench, January 20, 1971, Minshu Vol. 25, No. 1, p. 1) to support this conclusion.

The High Court's contrary finding was thus deemed to be based on an error in the interpretation of law that clearly affected its judgment. The Supreme Court found that the first-instance judgment, which had dismissed P's suit for cancellation on the grounds that the Notification was not an administrative disposition, was correct.

Implications of the Judgment

This Supreme Court decision offers several important takeaways for local governments, private entities participating in public procurement or privatization initiatives, and legal practitioners:

- Defining "Administrative Disposition": The case provides a clear illustration of the criteria used to determine whether an act by a public authority constitutes an "administrative disposition" subject to administrative review. A key factor is whether the act involves an "exercise of public authority" that directly affects the rights and obligations of a party. Mere communications regarding internal decisions related to entering (or not entering) into contracts, especially within a selection process not strictly mandated by law, may not meet this threshold.

- Discretionary Nature of Non-Mandated Selection Processes: When a local government uses a public solicitation or tender process as a discretionary method to select a contractual partner (rather than being bound by specific competitive bidding laws for that particular type of contract), the communications made during that process (like a notice of non-selection) are less likely to be considered formal administrative dispositions.

- Distinction from Designated Manager System: The Court clearly differentiated the legal framework for selecting designated managers (which often involves more formalized, legally prescribed procedures including public solicitation requirements under local ordinances) from the process of selecting a counterparty for an asset transfer, which may allow for negotiated contracts.

- Avenues for Challenging Decisions: If a notification of non-selection in such a discretionary process is not an administrative disposition, parties who believe they have been unfairly treated may need to explore other legal avenues, if any. These might theoretically include civil claims (e.g., for damages based on tort if bad faith or a breach of legitimate expectation in the selection process could be proven, or potentially a claim to compel contract conclusion if very specific conditions are met), though the prospects for such claims are often challenging and were not the subject of this specific ruling. The PDF commentary accompanying the case text suggests that public law party lawsuits or civil lawsuits might be conceivable alternatives.

- Importance of Contractual Framework: The judgment underscores that when local governments engage in privatization through asset sales or similar contractual arrangements, the underlying relationship is often viewed through the lens of contract law, even if public policy objectives are involved.

This ruling provides important guidance on the procedural rights of applicants in public selection processes and clarifies the scope of judicial review available for decisions made by local governments in the context of privatizing public assets or selecting service providers through non-statutorily mandated solicitation methods.