Private Lives, Workplace Rules: Japan's Supreme Court on Disciplining Off-Duty Misconduct (July 28, 1970)

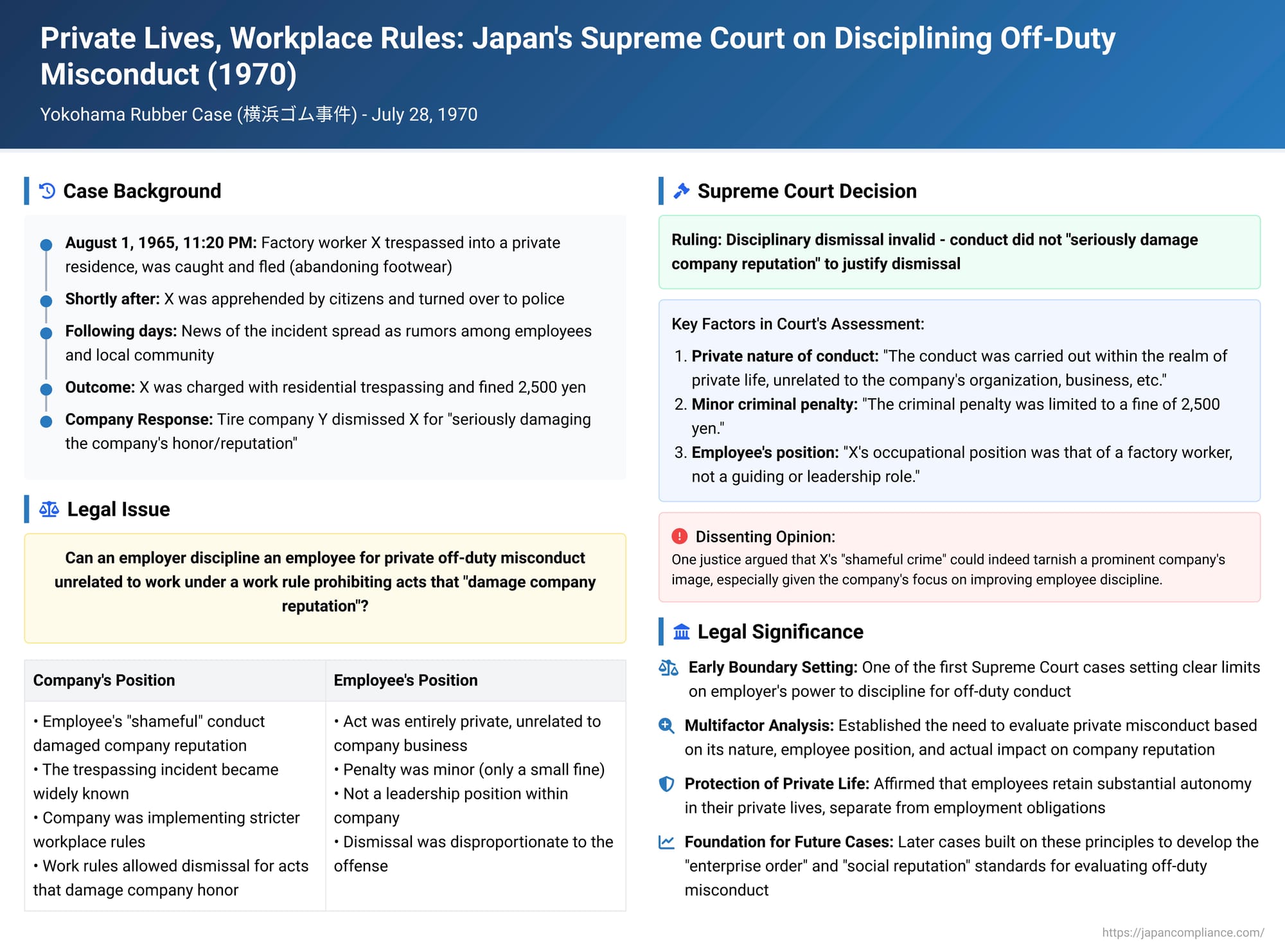

On July 28, 1970, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a judgment in a significant case commonly known as the "Yokohama Rubber Case" (横浜ゴム事件). This ruling was one of the earliest by Japan's highest court to address the complex issue of an employer's authority to discipline an employee for misconduct committed entirely within the employee's private life, outside of working hours and off company premises. The central question was whether such private actions could legitimately form the basis for a disciplinary dismissal under a work rule provision targeting conduct that "seriously damages the company's honor/reputation."

An Employee's Off-Duty Misstep

The plaintiff, X, was employed as a worker in the manufacturing section of a tire factory owned by Defendant Company Y. The incident that led to the dispute occurred in X's private time:

- On the night of August 1, 1965, around 11:20 PM, X trespassed into a private residence. X reportedly snuck into the home via its bathroom area. When confronted by a household member, X quickly fled the scene, even abandoning footwear in the haste to escape.

- Shortly thereafter, X was apprehended by private citizens and subsequently handed over to the police.

- News of X's offense and arrest quickly spread as a rumor within a few days, becoming known among residents living near Company Y's factory and also among Company Y's employees.

- As a result of this incident, X was charged with the crime of residential trespassing and was ultimately penalized with a fine of 2,500 yen.

Company Y's Disciplinary Dismissal

Following these events, Company Y decided to take severe disciplinary action. It dismissed X from employment, citing its internal "Rewards and Punishments Regulations." The specific ground for dismissal was a provision that allowed for disciplinary dismissal of an employee who "commits a wrongful or unjust act and seriously damages the company's honor/reputation" (不正不義の行為を犯し、会社の体面を著しく汚した者 - fusei fugi no kōi o okashi, kaisha no taimen o ichijirushiku kegashita mono).

X challenged the validity of this dismissal, leading to legal proceedings. Both the Tokyo District Court (first instance) and the Tokyo High Court (on appeal) ruled in favor of X, finding the disciplinary dismissal to be invalid. Company Y then appealed this outcome to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Dismissal Deemed Too Harsh

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby upholding the lower courts' decisions that the disciplinary dismissal of X was invalid.

In its reasoning, the Supreme Court acknowledged certain points in Company Y's favor:

- It recognized that X's conduct, considering the late hour and the nature of the trespass, was indeed of a "shameful nature" (恥ずべき性質の事柄 - hazubeki seishitsu no koto柄).

- It also noted that at the time of the incident, Company Y was reportedly engaged in efforts to improve its business operations, which included emphasizing strict adherence to workplace rules by its employees and a policy of consistently applying rewards and punishments.

- Furthermore, the Court acknowledged that the fact of X's offense and arrest had quickly become known within the local community and among the workforce.

Given these factors, the Supreme Court stated that there was "some understandable basis" (無理からぬ点がないではない - murikaranu ten ga nai dewa nai) for Company Y's decision to treat X's conduct seriously and resort to disciplinary dismissal.

However, the Supreme Court then critically evaluated whether X's actions truly met the threshold of "seriously damaging the company's honor/reputation" as stipulated in the disciplinary rule. It concluded that they did not, based on a comprehensive consideration of several key circumstances:

- Private Nature of the Conduct: "The conduct of [X] in question was carried out within the realm of what can be called private life, unrelated to the company's organization, business, etc."

- Minor Nature of the Criminal Penalty: "The criminal penalty [X] received was limited to a fine of 2,500 yen." This relatively small fine indicated the legal system viewed the offense as being on the lower end of the criminal spectrum.

- Employee's Position and Role: "[X's] occupational position within Company Y was that of a factory worker in charge of steam curing operations, which is not a guiding or leadership role."

Taking these factors together, the Supreme Court concluded: "Considering these various circumstances as found by the original judgment, it cannot but be said that it is inappropriate to evaluate X's said conduct as having 'seriously damaged [Company Y's] honor/reputation' to such an extent [as to justify dismissal]".

It is worth noting that one justice on the panel issued a dissenting opinion. The dissenting justice argued that X's "shameful crime" (破廉恥罪 - harenchizai) could indeed tarnish the image of a prominent company like Y, especially given the company's concurrent focus on improving employee morale and discipline. The dissent also contended that the distinction between a regular worker and a manager was less relevant in this context, as all employees contribute to the collective character of an enterprise.

The Evolution of Principles for Disciplining Private Misconduct

The Yokohama Rubber case was a significant early pronouncement by the Supreme Court on the sensitive issue of disciplining employees for their off-duty conduct. As noted by legal commentators, this specific judgment was more of a fact-centric ruling than one that laid down broad, abstract legal principles for all such future cases. It primarily focused on whether the specific facts met the high threshold of "seriously damaging the company's honor."

The broader legal framework for when and how employers can discipline employees for private life misconduct evolved more explicitly in subsequent Supreme Court decisions:

- The General Principle – Impact on "Enterprise Order" or "Social Reputation": Later landmark cases, such as the Kokutetsu Chūgoku Shisha Case (1974, involving a public corporation employee's conviction related to an off-duty demonstration), the Nihon Kōkan Case (1974, concerning factory workers disciplined for off-duty political activities leading to arrests), and the Kansai Denryoku Case (1983, involving off-duty leaflet distribution at company housing), established the general principle that private life misconduct can become a legitimate subject of workplace discipline if it:

- Has a "direct connection to enterprise order" (企業秩序に直接の関連を有するもの - kigyō chitsujo ni chokusetsu no kanren o yūsuru mono).

- Is "objectively recognized as likely to lead to the decline or damage of the company's [social] reputation" (その評価の低下毀損につながるおそれがあると客観的に認められるがごとき所為 - sono hyōka no teika kison ni tsunagaru osore ga aru to kyakkanteki ni mitomerareru ga gotoki shoi).

- "Severely negatively affects the company's social reputation" (会社の社会的評価に重大な悪影響を与えるような従業員の行為 - kaisha no shakaiteki hyōka ni jūdai na akueikyō o ataeru yōna jūgyōin no kōi).

- "Risks obstructing the smooth operation of the enterprise or otherwise relates to enterprise order" (企業の円滑な運営に支障を来すおそれがあるなど企業秩序に関係を有するもの - kigyō no enkatsu na unei ni shishō o kitasu osore ga aru nado kigyō chitsujo ni kankei o yūsuru mono).

- The Nihon Kōkan Criteria for Assessing Impact on Reputation: The Nihon Kōkan Case provided a more detailed set of factors for determining whether an employee's private act has "seriously damaged the company's honor/reputation." This requires a holistic assessment considering:

- The nature and circumstances of the employee's act itself.

- The type, mode, and scale of the company's business operations.

- The company's standing and position within the economic world.

- The company's prevailing management policies.

- The employee's specific position and job type within the company.

The act must be objectively evaluated as having a "considerably serious negative impact" on the company's social reputation to warrant discipline under such a clause. Applying these criteria in the Nihon Kōkan case itself, the Supreme Court found that the factory workers' off-duty political activities, which resulted in minor penalties and were not considered "shameful acts," did not meet this high threshold for dismissal, even if they might have slightly diminished the company's reputation.

- The Role of Media Coverage and Public Knowledge: Whether the employee's misconduct becomes publicly known, for instance through media reporting, is often a factor considered by courts. However, it is not necessarily decisive. In both the Yokohama Rubber and Nihon Kōkan cases, discipline was invalidated even though the incidents had become known to some extent. In later cases, significant negative media coverage impacting company credit has been a factor supporting the validity of disciplinary action for severe misconduct (e.g., the Nihon Yūbin Jigyō Kabushiki Kaisha Case, Tokyo High Ct. 2013). Conversely, discipline has been upheld for serious off-duty misconduct directly impacting company reputation even without media coverage (e.g., the Odakyū Dentetsu Case, concerning a railway employee's off-duty groping incident), while in other instances, discipline has been invalidated even with some public knowledge if the act was less severe and its impact on enterprise order was minimal (e.g., the Tokyo Metro Case, also involving a groping incident but with different circumstances).

- Nexus to Job Duties or Company Business: Courts tend to scrutinize private misconduct more strictly if it has a discernible connection to the employee's specific job responsibilities or the nature of the company's business. For example:

- In the Odakyū Dentetsu Case (Tokyo High Ct. 2003), the disciplinary dismissal of a railway company employee for an off-duty groping incident committed on a train was upheld. Aggravating factors included a prior similar offense by the employee, the company's active public campaign against sexual harassment on its trains, and the employee's inherent role in ensuring passenger safety.

- Similarly, in the Yamato Un'yu Case (Tokyo Dist. Ct. 2007), the disciplinary dismissal of a driver for a major transportation company who engaged in off-duty drunk driving was found valid. The court reasoned that such conduct by a professional driver, even in their private time, could severely undermine the company's social reputation and public trust, given the company's business and the strong societal expectation for transport companies to combat drunk driving.

The Balance: Employer Interests vs. Employee Privacy

This line of jurisprudence, starting with cases like Yokohama Rubber, reflects an ongoing effort by Japanese courts to balance the employer's legitimate need to protect its business interests, reputation, and internal order against the employee's fundamental right to a private life free from undue employer interference.

Academic commentators generally support the courts' cautious approach, often arguing that disciplinary power should primarily be confined to conduct directly related to the work performance process. While most now accept, in line with case law, that truly egregious private misconduct with a clear and substantial negative impact on legitimate company interests can be subject to discipline, there is a consistent call for this power to be exercised restrictively. This is particularly relevant today, as increasing corporate emphasis on compliance, ethics, and social responsibility could potentially lead to attempts to regulate a wider range of employees' off-duty behaviors, raising concerns about the encroachment on personal freedoms.

Conclusion: Early Recognition of Limits on Disciplining Private Conduct

The Supreme Court's 1970 decision in the Manufacturing Company YR (Yokohama Rubber) case was a significant early indicator from Japan's highest court that there are substantial limitations on an employer's authority to discipline employees for their actions in their private lives. While subsequent Supreme Court rulings have more explicitly articulated the general principle that private misconduct can be subject to discipline if it demonstrably harms legitimate company interests (such as enterprise order or social reputation), this foundational case emphasized that not all personal failings or minor legal infractions committed off-duty will justify severe disciplinary sanctions, particularly the ultimate penalty of dismissal for "damaging the company's honor." The Court's careful consideration of the private nature of the act, the minor legal consequences, and the employee's non-managerial status highlighted a protective stance towards employee autonomy outside the workplace, a principle that continues to inform the delicate balance between employer interests and employee privacy in Japanese labor law.