Preserving the State's Right to Collect: Japan's Supreme Court on Tax Collection Time Limits

Judgment Date: June 27, 1968

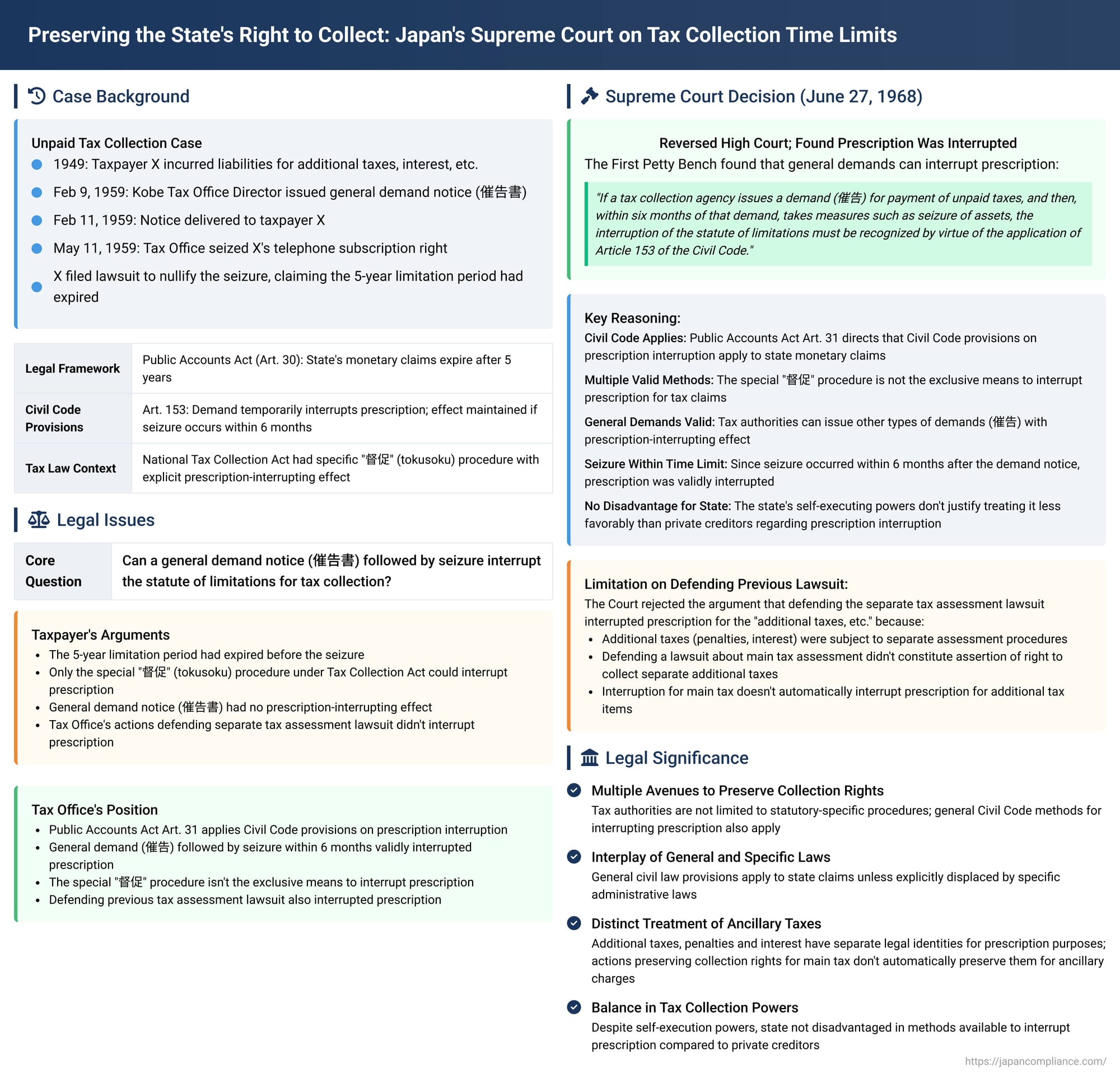

In a significant decision addressing the statute of limitations for the collection of national taxes, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan clarified how the government's right to collect can be preserved. The case delved into the interplay between the Public Accounts Act, the Civil Code's provisions on prescription (statute of limitations), and specific tax collection procedures, particularly concerning the effect of different types of demand notices issued by tax authorities. The ruling affirmed that general demands for payment, when followed by timely enforcement actions, can prevent the extinguishment of tax collection rights, even when specialized demand procedures also exist in tax law.

Background: A Taxpayer's Challenge to Seizure

The case originated from a dispute over unpaid taxes from the 1949 income tax year. The plaintiff, X (respondent on appeal), had accrued liabilities for various "additional taxes, etc." These included an additional tax (加算税 - kasanzei, typically a penalty for underpayment or failure to file), a supplementary collection tax (追徴税 - tsuichozei), interest tax (利子税 - rishizei), and a delinquency surcharge (延滞加算税 - entai kasanzei).

Due to X's failure to pay these amounts, Y, the Director of the Kobe Tax Office (appellant), issued a demand notice (saikokusho - 催告書) to X. Subsequently, as a measure to collect the delinquent taxes, Y seized X's telephone subscription right, a valuable asset at the time.

X initiated legal proceedings to have this seizure nullified. X's primary argument was that the government's right to collect these "additional taxes, etc." had been extinguished by the five-year statute of limitations prescribed by Article 30 of the Public Accounts Act.

The Kobe District Court (court of first instance) and the Osaka High Court (appellate court) both sided with X, finding that the tax collection right had indeed expired due to the passage of time. Dissatisfied with these outcomes, the Tax Office Director, Y, appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Central Legal Question: Interruption of the Statute of Limitations

The core issue before the Supreme Court was whether the statute of limitations for collecting the "additional taxes, etc." had been validly "interrupted" (中断 - chūdan), a concept under the then-existing Civil Code. (Under the Japanese Civil Code as amended in 2017, the concept of "interruption" has been replaced by "completion postponement" (完成猶予 - kansei yūyo) and "renewal" (更新 - kōshin) of prescription. However, the principles discussed in this 1968 case remain relevant to understanding how the running of the statute of limitations on tax claims can be affected by government action.)

Specifically, the Court had to determine:

- Whether a general demand for payment (saikoku) issued by the tax authority, followed by a seizure of assets within six months, could interrupt the statute of limitations for tax collection, by applying the provisions of the Civil Code.

- Whether the existence of a special type of demand notice called a "督促" (tokusoku) in the old National Tax Collection Act—which had its own statutory effect of interrupting prescription—precluded other forms of demand from having a similar effect under general Civil Code rules.

- Whether the tax authority's act of defending a separate lawsuit brought by X (challenging the underlying main income tax assessment) had interrupted the statute of limitations for the "additional taxes, etc." that were the subject of the current collection action.

The Supreme Court's Decision and Reasoning

The Supreme Court reversed the Osaka High Court's judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings. Its reasoning provided crucial clarifications on the application of prescription rules to tax collection rights.

1. Interruption of Prescription by Demand (saikoku) and Subsequent Seizure

This was the pivotal part of the ruling.

- Applicability of Civil Code Provisions: The Court affirmed that Article 31 of the Public Accounts Act was key. This article stipulated that for monetary claims of the State, if no other specific law provided rules for the interruption of the statute of limitations, the provisions of the Civil Code concerning such interruption should be applied. The Court stated it was "needless to say" that this provision applied to the right to collect national taxes.

- Effect of Demand Followed by Timely Action: Based on this, the Court reasoned that if a tax collection agency (徴税機関 - chōzei kikan) issues a demand (saikoku) for payment of unpaid taxes, and then, within six months of that demand, takes measures such as seizure of assets, the interruption of the statute of limitations must be recognized by virtue of the application of Article 153 of the (former) Civil Code. (Former Civil Code Article 153 effectively stated that a demand temporarily interrupts prescription, but this interruption loses its effect unless more definitive actions, like commencing judicial proceedings or, as in this case, seizure, are taken within six months. If such actions are taken, the prescription is more definitively interrupted, now understood as renewed by the seizure).

- Rejection of the Lower Courts' View on "督促" (tokusoku): The lower courts had adopted the view that the specific "督促" (tokusoku) procedure under the old National Tax Collection Act (Article 9, Paragraph 12 of which explicitly gave it prescription-interrupting effect irrespective of Civil Code Article 153) was the exclusive means by which a demand from a tax authority could interrupt prescription. They believed that because this special rule (tokusoku) existed, there was no room for applying Civil Code Article 153 to other, more general demands (saikoku). The Supreme Court found this interpretation to be unsupportable.

- Rationale for Disagreement: The Supreme Court explained that the tokusoku was incorporated into the National Tax Collection Act primarily as a formal procedural step. It served as a final warning and a prerequisite before the tax authorities could initiate compulsory collection measures like seizure (as stipulated in Article 10 of the old National Tax Collection Act), essentially setting one more defined due date for payment.

However, the existence of this specific tokusoku procedure did not mean that tax authorities were prohibited from issuing other types of demands, reminders, or urgings (saikoku shōyō - 催告慫慂) for payment. Even if such general demands did not carry any special independent legal weight within the formal collection procedure itself, there was no reason why the law could not attach the effect of interrupting prescription to the factual event of such a demand being made, recognizing it as a clear assertion of the right to payment. - No Basis for Less Favorable Treatment of the State: The Court also rejected the notion, seemingly underlying the lower courts' reasoning, that because the State's tax collection rights possess self-executing powers (自力執行性 - jiriki shikkōsei, meaning the tax authority can enforce collection without first obtaining a court judgment, unlike private creditors), the State should be treated less favorably than private creditors when it comes to the means of interrupting the statute of limitations. The Court saw no justification for such a disadvantageous interpretation against the taxing authority.

- Application to the Facts of the Case: In X's case, the Tax Office Director, Y, had issued a demand notice (saikokusho) on February 9, 1959, for the payment of the outstanding "additional taxes, etc." This notice was delivered to X on February 11, 1959. Subsequently, on May 11, 1959—well within the six-month period stipulated by former Civil Code Article 153—the seizure of X's telephone subscription right took place. The Supreme Court concluded that the lower court had erred in its interpretation and application of the law by not recognizing the interruption of the statute of limitations arising from these facts.

2. Interruption of Prescription by Defending a Lawsuit ("応訴行為" - ōso kōi)

The Court also addressed Y's argument that the statute of limitations for the "additional taxes, etc." had been interrupted because Y had defended a separate lawsuit previously filed by X. In that earlier lawsuit, X had challenged the validity of the underlying income tax assessment for the 1949 tax year. Y had argued that the assessment was not illegal and had sought the dismissal of X's claim. Y had won that lawsuit, and the judgment had become final and binding.

- Potential Interruption for the Main Tax: The Supreme Court acknowledged Y's argument that this act of defending the suit (ōso kōi) should be viewed as a form of judicial claim by the State, and thus should interrupt the statute of limitations for collecting the main income tax related to that assessment. The Court stated that such a line of reasoning was "not unpersuasive" (首肯できないものではない - shukō dekinai mono dewa nai), indicating a degree of receptiveness to the idea that defending a suit could, in substance, be equivalent to making a judicial claim for the purpose of interrupting prescription concerning the main tax.

- No Automatic Interruption for "Additional Taxes, etc.": However, the Court drew a crucial distinction when it came to the "additional taxes, etc." (penalties, interest, surcharges) that were the subject of the current seizure. It observed:

- While these additional levies were all related to the non-payment of the main income tax, under the tax laws applicable at that time, each of these "additional taxes, etc." was subject to separate assessment or determination procedures. They were ordered to be paid as liabilities distinct from the main income tax itself.

- Therefore, Y's act of defending the lawsuit concerning the main income tax assessment did not mean that Y had, within that specific lawsuit, judicially asserted the right to collect these distinct "additional taxes, etc."

- Furthermore, the Court held that an interruption of the statute of limitations for the main income tax collection right would not automatically or inherently interrupt the statute of limitations for the collection rights pertaining to these separately determined "additional taxes, etc."

On this point, the Supreme Court found that the lower court's conclusion—rejecting the argument that defending the suit about the main tax interrupted prescription for the ancillary "additional taxes, etc."—was not erroneous.

Outcome: Reversal and Remand

Given the lower court's error in not recognizing the interruption of prescription caused by the general demand (saikoku) followed by the timely seizure, the Supreme Court reversed the Osaka High Court's judgment.

The case was remanded for further proceedings. The remand was necessary because, even with the interruption, it was possible that the statute of limitations for some components of the "additional taxes, etc." (the Court specifically mentioned the interest tax) might have already expired before Y's demand notice was issued in February 1959. The lower court would need to re-examine the timeline for each specific tax component and determine the validity and appropriateness of the seizure concerning any remaining legally collectible amounts.

Significance of the Ruling

This 1968 Supreme Court decision has several important implications for understanding the statute of limitations in Japanese tax law:

- General Demands Can Preserve Collection Rights: It clarified that tax authorities are not limited to using only the specialized "督促" (tokusoku) procedure to interrupt (or, in modern terms, achieve completion postponement and renewal of) the statute of limitations. A general demand for payment (saikoku), if followed by legally prescribed actions like seizure within the statutory timeframe (formerly six months under Civil Code Art. 153), is also effective.

- Interplay of General and Specific Laws: The judgment illustrates the principle that general civil law provisions (like those in the Civil Code concerning prescription) can apply to State claims, including tax collection rights, unless specific administrative laws explicitly provide otherwise or create a system that fully displaces general law.

- Distinct Nature of Ancillary Taxes for Prescription: The decision underscored that, at least under the legal framework at the time, ancillary tax liabilities like penalties and interest were treated as distinct from the primary tax debt for the purposes of the statute of limitations. An action preserving the collection right for the main tax did not automatically preserve it for all related ancillary charges. (It is worth noting that legal commentary indicates that subsequent amendments to tax laws, particularly the General Act of National Taxes, have modified this aspect for certain types of ancillary taxes like delinquency tax and interest tax, linking their prescription more closely to the main tax).

- Fairness to the Taxing Authority: The Court's refusal to place the State in a more disadvantageous position than private creditors regarding the means to interrupt prescription, despite the State's self-execution powers, reflects a balancing approach to the rights and remedies available to parties in tax matters.

This ruling remains a key reference for issues concerning the timely enforcement of tax obligations and the measures available to tax authorities to prevent the expiry of their collection rights due to the passage of time.