Preserving Future Claims: Japanese Supreme Court on Provisional Attachment for Unmatured Child Support with Existing Enforceable Title

Date of Supreme Court Decision: January 31, 2017

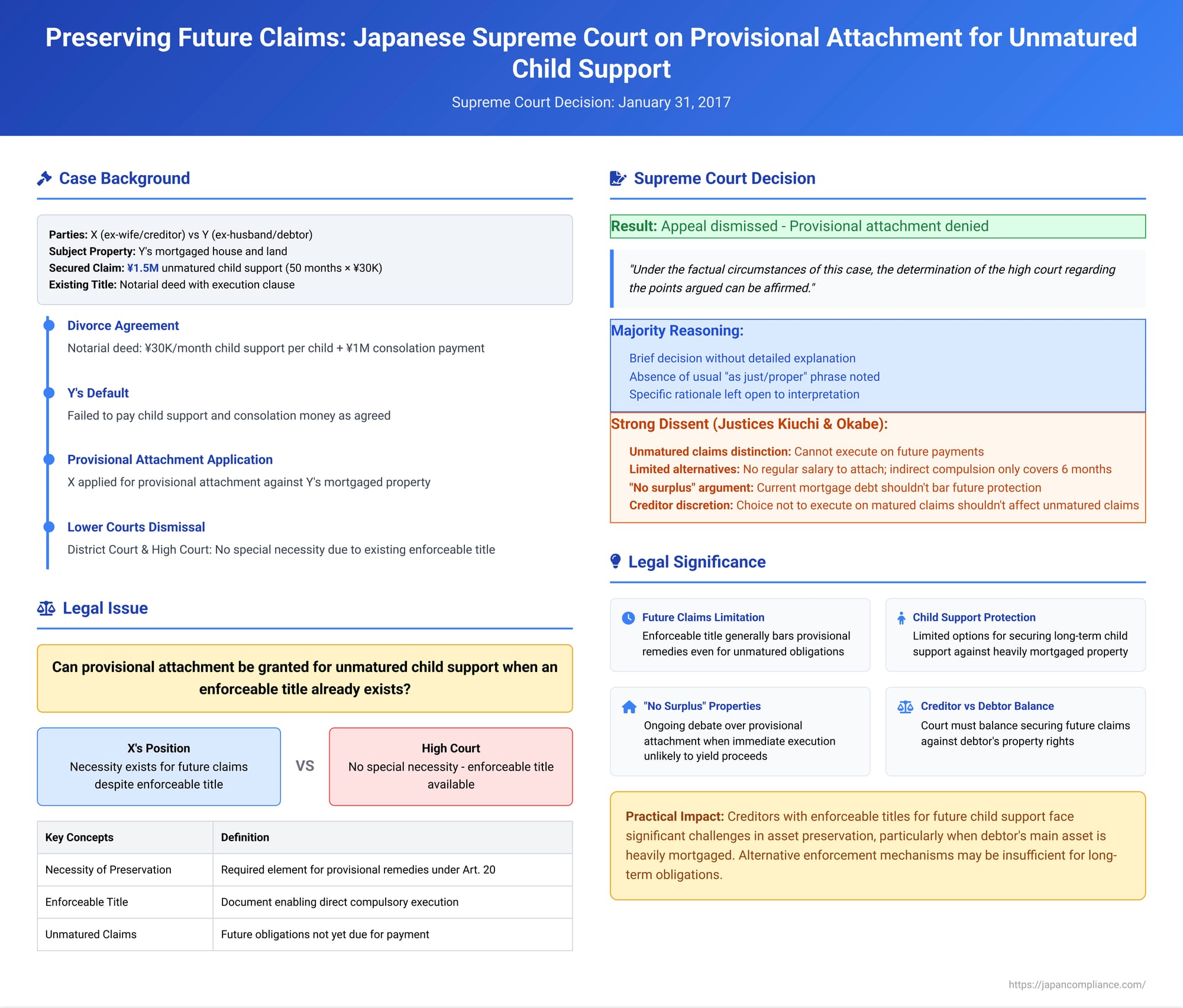

Civil provisional remedies, such as provisional attachment (仮差押え - karisashiosae), serve as crucial tools for creditors to secure assets before a final judgment or full enforcement is possible, preventing a debtor from dissipating property that might satisfy a future claim. However, a foundational principle dictates that if a creditor already possesses an "enforceable title" (債務名義 - saimu meigi), like a final judgment or a notarial deed with an execution clause, provisional remedies are generally deemed unnecessary because direct compulsory execution can be initiated. A 2017 Supreme Court of Japan decision (Heisei 28 (Kyo) No. 39) delved into a nuanced aspect of this principle: the availability of provisional attachment for unmatured future claims (specifically child support payments) when these are covered by an existing enforceable title, and where the debtor's only significant asset is already mortgaged.

The Factual Background: Unpaid Support and a Mortgaged Asset

The case involved X (the ex-wife and creditor) and Y (the ex-husband and debtor). Following their divorce by mutual agreement, they created a notarial deed with an execution clause. This deed stipulated Y's obligations to X, including:

- Child support payments of ¥30,000 per month for each of their two children, A and B.

- A one-time consolation payment (慰謝料 - isharyō) of ¥1 million.

Y subsequently defaulted on these payments. Meanwhile, Y had purchased a house and land (referred to as the "subject real property"), where he resided. This property was encumbered by a mortgage in favor of the Japan Housing Finance Agency.

X applied to the court for a provisional attachment order against Y's subject real property. The specific claim X sought to secure with this provisional attachment (the 被保全債権 - hihozen saiken) was the unmatured portion of child support for their son A, amounting to 50 months of payments from February 2016 onwards, totaling ¥1.5 million. It's important to note that at the time of this application, there were also already matured and unpaid child support installments for both children A and B, as well as the unpaid consolation money, all covered by the same notarial deed.

The court of first instance (Tokyo District Court, Tachikawa Branch) dismissed X's application for provisional attachment. X appealed, but the Tokyo High Court also dismissed the appeal. The High Court reasoned that X already possessed an enforceable title (the notarial deed) covering the claims. Therefore, it found no "special necessity to seek protection of rights by using the civil provisional remedy system". X then brought a permitted appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Core Legal Question: "Necessity of Preservation" with an Enforceable Title for Future Claims

The central issue was whether X demonstrated the "necessity of preservation" (保全の必要性 - hozen no hitsuyōsei), a key requirement for granting provisional remedies under Article 20 of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act. Generally, if a creditor can immediately initiate compulsory execution using an existing enforceable title, the necessity for a provisional remedy like attachment is considered lackin.

However, exceptions exist, primarily when immediate execution is not feasible despite the presence of an enforceable title. This case tested whether future, unmatured child support obligations, though covered by an enforceable notarial deed, fell into such an exceptional category, particularly when the debtor's main asset was heavily mortgaged.

The Supreme Court's Majority Decision (and its Brevity)

The Supreme Court, by a majority vote, dismissed X's appeal, thereby denying the provisional attachment. The majority opinion was remarkably brief, stating: "Under the factual circumstances of this case, the determination of the high court regarding the points argued can be affirmed. The arguments are not accepted".

Legal commentators have noted the absence of the usual phrase "as just/proper" (正当として - seitō to shite) in the affirmation, which might suggest that the Supreme Court, while upholding the outcome, did not necessarily endorse the entirety of the High Court's reasoning. The brevity leaves the precise rationale of the majority somewhat open to interpretation.

The Dissenting Opinion: A Strong Counter-Argument

Justice Michiyoshi Kiuchi, joined by Justice Kiyoko Okabe, issued a strong dissenting opinion, arguing that the provisional attachment should have been granted. Their reasoning provides valuable insight into the complexities of the case:

- Unmatured Claims are Distinct: The dissent emphasized that an enforceable title for claims not yet due is fundamentally different from one for claims already matured. Compulsory execution generally cannot be initiated for unmatured claims (as per Article 30 of the Civil Execution Act). Therefore, having an enforceable title for future payments doesn't automatically negate the need for provisional measures to secure them.

- Limitations of Other Enforcement Tools for Future Child Support:

- Attachment of Salary/Recurring Payments (Civil Execution Act Art. 151-2): While this article allows for the attachment of future installments of child support from sources like salary, the dissent noted that Y (the debtor) was not found to have such regular income, making this option unavailable to X.

- Indirect Compulsion (Civil Execution Act Art. 167-16): This article permits indirect compulsion (a court order compelling performance under threat of penalty) for unmatured child support, but it is restricted to claims maturing within six months. X's claim for future support for child A alone spanned 50 months (totaling ¥1.5 million), and for child B, it was 68 months (¥2.04 million), making a combined total of ¥3.54 million in unmatured claims at the time of the application. Indirect compulsion was thus not a comprehensive solution.

- Creditor's Discretion Regarding Matured Claims: The dissent argued that X's decision not to immediately initiate a compulsory auction of Y's property for the already matured arrears (which amounted to approximately ¥1.39 million for both children, plus the ¥1 million consolation money) should not negatively impact her ability to take preservative measures for the separate, unmatured future child support claims. A creditor might have valid economic reasons to hesitate before forcing an auction (e.g., high costs, risk of low sale price, especially if the property is already heavily mortgaged).

- The "No Surplus" (無剰余 - mujoyo) Property Argument:

- Y's property was mortgaged to the Japan Housing Finance Agency, and the dissent acknowledged a "considerable possibility" that an auction might yield no surplus after satisfying the mortgage and auction costs.

- However, the dissent contended that this should not automatically defeat the necessity for provisional attachment of future claims. Even when a creditor applies for provisional attachment before obtaining an enforceable title (i.e., in anticipation of a future lawsuit), provisional attachment is often granted despite a current risk of "no surplus." This is because the property's value might increase, or the mortgage debt might decrease by the time compulsory execution for the (then matured) claim becomes possible. The provisional attachment serves to secure the asset against disposal by the debtor in the interim.

- The dissent reasoned that this same logic should apply when the creditor already has an enforceable title for future claims but cannot yet execute on them. The current degree of "no surplus" possibility should not be a bar if a future surplus is not deniable.

- Furthermore, the dissent pointed out that if Y owned multiple properties, X could only levy execution on property proportionate to her matured claims. If other properties existed that could not be reached by the matured claims, a provisional attachment would be necessary for the unmatured claims to prevent Y from disposing of those other assets.

"Necessity of Preservation" vs. "Necessity for Protection of Rights"

Japanese legal scholarship and some court decisions distinguish between the "necessity of preservation" (hozen no hitsuyōsei) as a substantive requirement for provisional remedies under Article 20 of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act, and a more general concept sometimes termed "necessity for protection of rights" (kenri hogo no hitsuyōsei). The latter is often seen as analogous to the "benefit of suit" (uttae no rieki) required in full litigation. If a creditor already has an enforceable title and can proceed with direct execution, this broader "necessity for protection of rights" via provisional remedies is generally considered lackin. The High Court in this case framed its dismissal on X lacking the "special necessity for protection of rights".

It has been observed that a prior Supreme Court decision (September 6, 2012) affirmed a lower court's dismissal of a provisional attachment application (where an enforceable title existed for a damages claim) due to a lack of "necessity for protection of rights," using the phrase "can be affirmed as just/proper" (正当として是認することができる). The current decision's slightly different phrasing ("can be affirmed") might indicate a less complete endorsement of the lower court's specific reasoning, although the outcome was the same.

Exceptions: When is Provisional Attachment Permitted Despite an Enforceable Title?

The general rule is that an existing enforceable title negates the need for provisional attachment. However, exceptions are recognized, primarily when special circumstances prevent immediate and effective compulsory execution despite the title. Examples include:

- When the enforceable title is subject to a condition or pertains to a future due date (as was the case with X's unmatured child support claims).

- When the execution of the title has been stayed by a court order.

- When significant time is required for procedures like serving the title or obtaining further necessary writs (e.g., a succession execution writ for enforcing against an heir).

The High Court in X's case appeared to believe that because X could immediately sue for the matured child support and consolation money, no special circumstances warranted provisional attachment for the unmatured portion of the same overall child support stream. The dissent strongly contested this, arguing for the separate consideration of unmatured claims.

The "No Surplus" Property Issue in Provisional Attachment

The question of whether provisional attachment should be granted against a property likely to yield "no surplus" (i.e., where a forced sale wouldn't cover prior mortgages and costs) is a debated point in Japanese law:

- Affirmative View: Some argue for allowing it, especially if there's a risk of the debtor hiding or disposing of the asset, and if there's a possibility of a surplus emerging in the future (e.g., due to property value appreciation or mortgage paydown).

- Negative View: Others contend that since compulsory execution is technically still possible even in a "no surplus" scenario (e.g., the creditor can offer to buy the property themselves under Civil Execution Act Art. 63(2)), allowing a provisional attachment that might last indefinitely for an uncertain future surplus places an undue burden on the debtor and oversteps the intended role of provisional remedies.

- Eclectic View: A middle ground suggests that necessity might be found if there's a reasonable prospect of a surplus arising in the near future.

The High Court in X's case, while acknowledging a "considerable possibility" of no surplus, did not find this to be an absolute impediment because the situation was not as definitive as, for example, a previous auction attempt on the same property having already been cancelled for no surplus. The dissent, as noted, argued that the current possibility of no surplus should not be determinative if a future surplus cannot be ruled out, especially for securing long-term future claims. The Supreme Court majority did not explicitly engage with these varying views on the "no surplus" issue in its brief decision.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's majority decision in this case, by virtue of its brevity and fact-specific affirmation ("Under the factual circumstances of this case..."), offers limited general guidance beyond the outcome itself. It denied provisional attachment for future child support payments despite an existing enforceable notarial deed. However, the detailed and compelling dissenting opinion highlights the significant arguments in favor of allowing such provisional measures, particularly for long-term, essential obligations like child support where the debtor's financial stability can be precarious and immediate enforcement of the entire future stream is impossible.

The case underscores the ongoing judicial and academic deliberation in Japan regarding the precise scope of "necessity" for provisional remedies when an enforceable title exists, especially concerning future claims and properties with questionable immediate equity. It reflects the inherent tension in provisional remedy law: balancing a creditor's legitimate need to secure future payments against a debtor's right to be free from potentially long-lasting restrictions on their property, particularly when alternative, albeit partial or delayed, enforcement avenues might be available for matured portions of the debt. The debate over how to treat "no surplus" properties in the context of provisional attachments also remains a significant point of discussion in Japanese civil procedure.