Pregnancy, Lighter Duties, and Demotion: A Japanese Supreme Court Landmark on Worker Protection

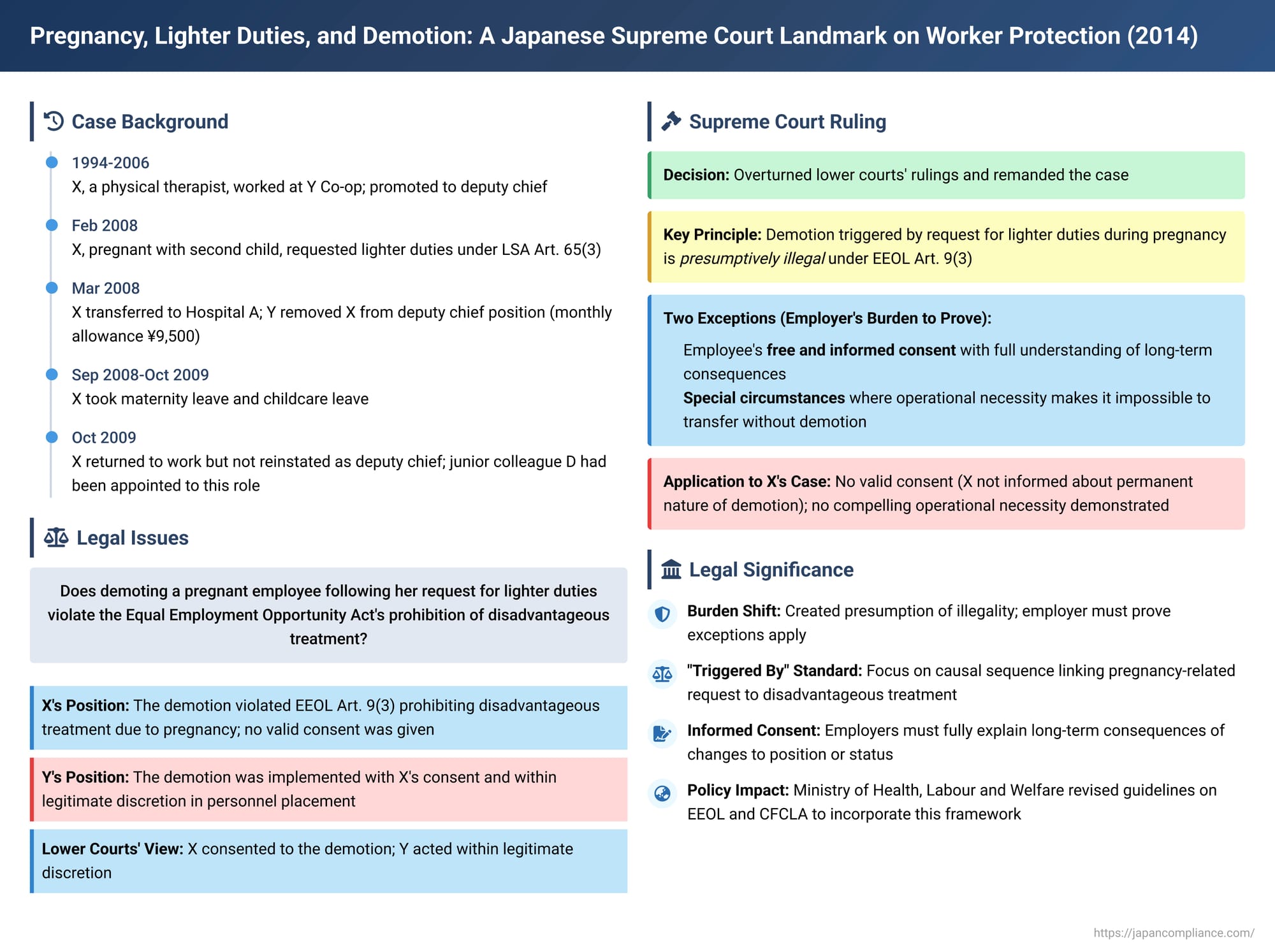

The journey of pregnancy brings with it unique joys and challenges, and for working women, one significant challenge can be navigating workplace accommodations and ensuring career continuity. Japanese law provides several protections for pregnant employees, including the right to request lighter duties under the Labor Standards Act (LSA) and prohibitions against disadvantageous treatment due to pregnancy or childbirth under the Equal Employment Opportunity Act (EEOL). A pivotal Supreme Court of Japan decision on October 23, 2014, in what is commonly known as the Hiroshima Chuo Health Co-operative Society case, profoundly clarified the extent of these protections, particularly when a request for lighter duties is followed by a demotion.

The Case Background: A Physical Therapist's Predicament

The plaintiff, X, was a dedicated physical therapist employed by Y, a healthcare and nursing care provider (referred to as "the Co-op") since March 1994. By April 2006, X had risen to the position of deputy chief, overseeing hospital rehabilitation services at Hospital A or leading home-visit rehabilitation services at Facility B.

In February 2008, X, then pregnant with her second child, was engaged in home-visit rehabilitation work based at Facility B. Citing Article 65, Paragraph 3 of the Labor Standards Act, she requested a transfer to lighter duties, specifically seeking a move to hospital-based rehabilitation work, which was considered less physically demanding. In response, Y transferred X from Facility B to the rehabilitation department at Hospital A on March 1, 2008. At Hospital A, a more senior employee, C, was already serving as chief and managing the department's operations.

Around mid-March 2008, Y informed X that it had overlooked issuing an order to remove her from the deputy chief position at the time of her transfer. X, though reluctant, acquiesced to this. Concerned that a demotion effective April 1st might be perceived by colleagues as resulting from a mistake on her part, X requested that the demotion be backdated to her transfer date of March 1st. Consequently, on April 2, 2008, Y issued a formal order transferring X to Hospital A and simultaneously relieving her of her deputy chief position, effective March 1, 2008 (this demotion is referred to as "the measure in question"). The deputy chief position carried a monthly allowance of 9,500 yen.

After taking maternity leave (September 1, 2008 - December 7, 2008) and subsequent childcare leave (December 8, 2008 - October 11, 2009), X prepared to return to work. Y, after consulting X about her preferences, assigned her back to Facility B on October 12, 2009. However, by this time, another employee, D, who had a shorter career history as a physical therapist than X, had been appointed deputy chief at Facility B shortly after X's demotion. As a result, X was not reinstated to her deputy chief role and had to work under D. X strongly protested this situation (the failure to reinstate her is referred to as the "measure at the time of return") and subsequently filed a lawsuit.

X claimed primarily that her demotion ("the measure in question") was void for violating the Equal Employment Opportunity Act (EEOL) or, secondarily, that the failure to reinstate her as deputy chief upon her return ("measure at the time of return") violated the EEOL or the Childcare and Family Care Leave Act (CFCLA). She sought payment of the deputy chief allowance and damages. The Hiroshima District Court and the Hiroshima High Court both ruled against X, finding that the demotion was implemented with her consent and fell within Y's legitimate discretion in personnel placement. X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Intervention: A New Framework

In its judgment on October 23, 2014, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan overturned the lower courts' decisions and remanded the case for further consideration, establishing a critical legal framework for such cases.

EEOL Article 9, Paragraph 3 as a Mandatory Provision:

The Court began by affirming the nature and purpose of Article 9, Paragraph 3 of the EEOL. This provision prohibits employers from dismissing or otherwise treating female workers disadvantageously on grounds of pregnancy, childbirth, requesting pre-natal leave, taking pre or post-natal leave, or other reasons related to pregnancy or childbirth as specified by Ministry ordinance (which includes transferring to lighter duties under LSA Article 65(3)). The Supreme Court unequivocally stated that EEOL Article 9(3) is a mandatory provision (強行規定, kyōkō kitei). This means its protections cannot be overridden by private agreement if doing so would contravene the law's purpose. Any employer action violating this provision is illegal and void.

The Core Principle: Presumptive Illegality of Demotion Linked to Lighter Duties:

The Court then laid down a crucial principle: an employer's measure to demote a female worker that is triggered by (契機として, keiki toshite) her transfer to lighter duties during pregnancy is, in principle, considered disadvantageous treatment prohibited by EEOL Article 9(3). This establishes a presumption of illegality.

The Two Exceptions (Employer's Burden of Proof):

However, the Court acknowledged two exceptional circumstances where such a demotion would not violate the EEOL. The burden of proving these exceptions lies squarely with the employer.

- Employee's Free and Informed Consent:

The demotion is permissible if "objectively reasonable grounds exist to recognize that the worker consented to the demotion based on her free will". This assessment requires considering:- The nature and extent of any advantageous effects for the worker (e.g., reduced workload from the lighter duties and the demotion itself) and disadvantageous effects (e.g., loss of status, pay).

- The content of the employer's explanation regarding the demotion and other circumstances leading to it.

- The worker's own intentions and preferences.

Critically, for consent to be deemed free and informed, the employer must have provided an adequate explanation of the demotion's impact, enabling the worker to fully understand the consequences before deciding. - Application to X's case: The Supreme Court found no such valid consent. While X transferred to lighter duties, it was unclear if the demotion itself further significantly reduced her workload beyond what the transfer already achieved. The disadvantages were substantial: loss of managerial status held for over 10 years and the associated allowance. Crucially, the demotion was not a temporary measure for the lighter-duty period but a lasting one, as Y did not plan to reinstate her as deputy chief after her childcare leave—a fact Y apparently failed to explain to X before she "reluctantly agreed" to the demotion. Without a full understanding of these long-term implications, X could not have given free and informed consent.

- Overriding Operational Necessity ("Special Circumstances"):

The demotion may be permissible if "there are special circumstances where, due to operational necessities such as ensuring smooth business operations or appropriate personnel allocation, it would be difficult for the employer to have the worker transfer to lighter duties without implementing the demotion, and in light of the nature and extent of such operational necessity as well as the nature and extent of the aforementioned advantageous or disadvantageous effects on the worker, the measure is found not to substantively violate the purpose and objective of Article 9(3) of the EEOL".- Application to X's case: The Court found that Y had not sufficiently demonstrated such "special circumstances". It was unclear what specific operational difficulties would have arisen if X had been transferred to lighter duties at Hospital A while retaining her deputy chief status, perhaps assisting the existing chief. Given that the demotion appeared to be long-term and contrary to X's career aspirations, and the actual reduction in burden due to the demotion (distinct from the transfer) was not clearly established, the Court could not find that the demotion was justified by overriding operational needs in a way that didn't violate the spirit of the EEOL.

The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court had failed to adequately examine these crucial points and had misapplied the law, thus warranting a remand for reconsideration based on this new framework.

The Rationale: Strengthening Protections for Pregnant Workers

This judgment marked a significant shift in the interpretation and application of EEOL Article 9(3). Previously, employees often faced an uphill battle to prove that such personnel actions were an abuse of the employer's discretionary power or were directly "because of" pregnancy-related events. The Supreme Court's 2014 ruling effectively reversed the onus: once an employee demonstrates that a demotion (or other disadvantageous treatment) was "triggered by" a pregnancy-related event like a request for lighter duties, the treatment is presumed unlawful. The employer must then robustly prove either genuine, informed consent or truly compelling operational necessities that meet the stringent criteria set by the Court.

The Court's framework seeks to strike a balance. It acknowledges that employers have legitimate operational needs, but these needs cannot automatically override a pregnant worker's statutory right to protection from disadvantageous treatment. The emphasis on "free and informed consent" ensures that any agreement to a potentially disadvantageous change is genuine and not a result of pressure or incomplete information. Similarly, the "special circumstances" exception demands a high threshold of proof, preventing employers from citing vague or minor inconveniences as justification for actions that could undermine a pregnant employee's career or working conditions.

Justice Sakurai's Supplementary Opinion

Justice Sakurai Ryuko offered a supplementary opinion, which, while not part of the main judgment binding the remand, provided further insights, particularly concerning X's secondary claim about the failure to reinstate her as deputy chief after her childcare leave. This aspect relates to Article 10 of the Childcare and Family Care Leave Act (CFCLA), which also prohibits disadvantageous treatment for taking childcare leave.

Justice Sakurai emphasized that:

- Article 10 of the CFCLA should also be considered a mandatory provision.

- When assessing whether a failure to reinstate after childcare leave constitutes a demotion or disadvantageous treatment, the comparison should be with the employee's position before the pregnancy-related lighter duties transfer, not with the (potentially temporary) status during that period. This is because the lighter duty transfer is inherently temporary for the duration of pregnancy.

- While exceptions similar to those under EEOL Art. 9(3) (free consent or special operational necessity) might apply, the CFCLA also places obligations on employers to endeavor to pre-determine and notify employees about their post-leave positions and working conditions, and to manage personnel considering the widespread practice of reinstatement to the original or an equivalent position.

- In X's case, Y appointed a less experienced employee to X's former deputy chief role at Facility B shortly after X was demoted and transferred. This action, making X's reinstatement to her original team and role difficult, would weigh heavily against Y in assessing whether "special circumstances" existed to justify not reinstating her. Furthermore, the lack of adequate explanation to X about her post-leave prospects before she took leave was problematic.

Implications and Significance of the Ruling

The Hiroshima Chuo Health Co-operative Society case has had a profound impact on employment practices in Japan:

- Strengthened Protections: It significantly bolstered legal protections for pregnant employees and those taking childcare leave by making it easier to challenge disadvantageous treatment.

- Burden of Proof Shift: The establishment of a presumption of illegality once a link between a pregnancy-related event and disadvantageous treatment is shown is a major jurisprudential development.

- Employer Responsibilities: Employers are now under greater pressure to:

- Handle requests for lighter duties with extreme care, ensuring that any associated changes to an employee's status or terms are genuinely consensual or absolutely necessary.

- Provide comprehensive and transparent explanations to employees about the potential impacts of any such changes, both short-term and long-term.

- Thoroughly document the objective operational necessities if they believe a demotion or other potentially disadvantageous measure is unavoidable.

- "Triggered By" Standard: The Court's use of the "triggered by" (keiki toshite) standard, rather than a stricter "reason for" (riyū toshite) standard, makes it easier for an employee to establish a prima facie case of discrimination. The focus is on the causal sequence: did the pregnancy-related request initiate the chain of events leading to the demotion?

- Administrative Guidance: Following this judgment, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare revised its interpretative circulars on the EEOL and CFCLA to reflect this new judicial framework, extending its principles to various forms of disadvantageous treatment related to pregnancy, childbirth, and childcare leave. While some legal scholars debate whether the "free consent" exception is universally applicable to all types of disadvantageous treatment or primarily suits situations like this case where there's a mix of potential advantages (lighter work) and disadvantages (demotion), the administrative stance has broadened its application.

Conclusion

The 2014 Supreme Court decision in the Hiroshima Chuo Health Co-operative Society case represents a significant advancement in Japanese labor law, reinforcing the nation's commitment to ensuring that pregnant employees are not unfairly penalized for exercising their statutory rights. It sends a clear message to employers that policies and practices must genuinely support pregnant workers and those on childcare leave. The ruling champions the idea that accommodating pregnancy-related needs should not come at the cost of an employee's career progression or status, unless truly exceptional and justifiable circumstances, proven by the employer, dictate otherwise. This case underscores the importance of fostering a workplace culture where legal protections are not viewed as mere compliance hurdles but as essential components of fairness, equality, and respect for all employees.