Powering Down Transparency? Japan's Supreme Court on Disclosing Factory Energy Use Data

Judgment Date: October 14, 2011

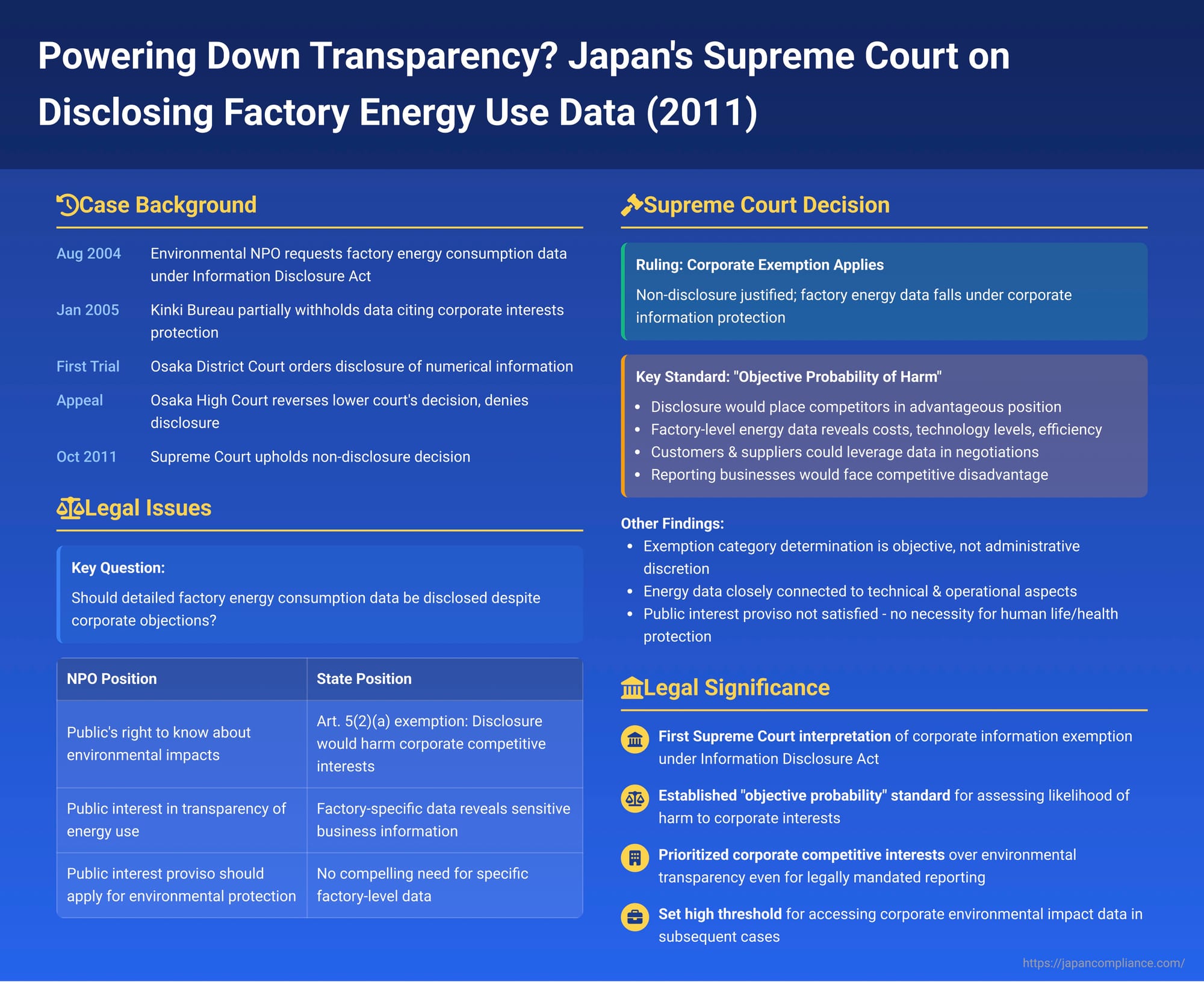

The disclosure of corporate information under freedom of information laws often ignites a debate between the public's right to know, particularly concerning environmental impact, and the protection of a company's competitive interests. A Japanese Supreme Court decision on October 14, 2011 (Heisei 20 (Gyo-Hi) No. 11), addressed this delicate balance in a case concerning the release of factory-specific energy consumption data. This ruling provided a significant interpretation of the corporate information exemption within Japan's Act on Access to Information Held by Administrative Organs.

The Data Request: An NPO Seeks Energy Consumption Details

The case was initiated by X, an environmental NPO (Non-Profit Organization), which, on August 6, 2004, filed a request under the Act on Access to Information Held by Administrative Organs (Information Disclosure Act) (prior to its 2005 amendment). The request was directed to the Kinki Bureau of Economy, Trade and Industry Director (the "deciding administrative agency"). X sought the disclosure of periodic annual reports for Fiscal Year 2003, which had been submitted by various business operators pursuant to the Act on the Rational Use of Energy (Energy Saving Act) (prior to its 2005 amendment). Specifically, X requested numerical information detailing the usage of fuel, electricity, and other energy sources at certain factories (this specific data is hereinafter referred to as "the numerical information").

On January 6, 2005, the deciding administrative agency issued a decision to partially disclose the reports. However, it withheld the numerical information for some factories, asserting that this data constituted non-disclosable information under Article 5, item 2(a) of the Information Disclosure Act. This provision exempts information concerning corporations or business-operating individuals if its disclosure is likely to harm their rights, competitive position, or other legitimate interests. X subsequently filed a lawsuit against the State (Y) seeking the cancellation of this non-disclosure decision concerning the numerical information and a court order compelling its disclosure.

The Legal Battle: From District Court to the Supreme Court

The Osaka District Court, at the first instance, ruled in favor of X regarding the numerical information, ordering its disclosure. However, the Osaka High Court, in the second instance, overturned the part of the District Court's decision that favored X, thereby rejecting X's claim for disclosure of the numerical information. Following this, X filed a petition for acceptance of a final appeal with the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (October 14, 2011): Protecting Corporate Interests

The Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, ultimately dismissed X's appeal, affirming the High Court's conclusion that the numerical information was indeed non-disclosable. The Court's reasoning was detailed and multi-faceted.

No Agency Discretion on Exemption Category

Firstly, the Supreme Court addressed the High Court's approach. The High Court had reviewed the agency's decision based on whether the agency had abused its discretion. The Supreme Court clarified that whether the numerical information falls under the non-disclosure category of Article 5, item 2(a) is a matter to be determined objectively based on the presence or absence of circumstances fulfilling the requirements of that provision. It is not a matter left to the discretionary judgment of the deciding administrative agency. While the High Court's reasoning on this point was deemed incorrect, its ultimate conclusion to deny disclosure was upheld by the Supreme Court on other grounds.

Characterizing the Energy Data

The Supreme Court then meticulously analyzed the nature of the numerical information in question:

- The data comprised specific figures for various types of energy used in particular factories during a specific fiscal year, including year-on-year comparisons. This information is typically managed internally by the respective business operators and is intimately connected to their technical and operational aspects as manufacturers.

- The Court drew a comparison with the disclosure regime under the Act on Promotion of Global Warming Countermeasures (Global Warming Countermeasures Act), as amended in 2005. This Act established a system for publishing and disclosing calculated greenhouse gas emissions. Even within this system—which deals with data at the business-site level (generally more abstract than the factory-level energy usage data at issue) and focuses on CO2 emissions derived from energy use—there are specific provisions designed to limit the scope of disclosure out of consideration for the rights and interests of business operators. The Supreme Court viewed this as indicative of the close relationship between such energy-related data and the legitimate interests of businesses.

- The purpose of the reporting system under the Energy Saving Act was identified as twofold: to encourage business operators themselves to meticulously track, organize, and analyze their energy usage, and to enable the government to grasp detailed, specific numerical data on energy use annually from each operator to provide appropriate guidance and instructions. The Supreme Court stated that any consideration of the scope of disclosure under the Information Disclosure Act must take into account the nature of such information and ensure consistency with the objectives of the Energy Saving Act's reporting system.

Assessing the "Likelihood of Harm"

The core of the Supreme Court's decision rested on its assessment of whether disclosing the numerical information would harm the legitimate interests of the reporting businesses.

- The Court noted the high degree of specificity in the numerical information: it was at the factory level, not merely company-wide; it consisted of detailed, raw, unprocessed data on items prescribed by law; and it inherently reflected the performance of energy-saving technologies at these factories. Given that these reports are submitted annually and include year-on-year comparative figures, comprehensive analysis of this data could enable highly accurate estimations of energy costs, manufacturing costs, levels of energy-saving technology, and their trends over time at each factory.

- Impact on Competitors: If disclosed, competitors could utilize this detailed information for their own strategic purposes, such as improving their equipment and technology development plans.

- Impact on Customers (Demanders): Customers purchasing products from these factories could analyze the data to estimate energy and manufacturing costs and their trends, potentially using this as objectively backed leverage in price negotiations.

- Impact on Suppliers: Suppliers of fuel and other energy sources could also use the disclosed data as objective information to strengthen their position in price negotiations with the business operators.

- Vulnerability of Reporting Businesses: The Court recognized that the business operators in question were private manufacturing enterprises. The specific items and details required in the energy usage reports are mandated by law, leaving these businesses with no discretion to modify their submissions or use carefully chosen language to mitigate potential negative consequences from future disclosure. Furthermore, compliance with these reporting obligations is enforced by penalties for non-submission. Consequently, if the numerical information were to be disclosed, the Supreme Court found it would be extremely difficult for these businesses to avoid being placed in a disadvantageous competitive or negotiating position.

Conclusion: Data Qualifies for Non-Disclosure under Article 5, item 2(a)

Based on a comprehensive consideration of the content, nature, and legal status of the numerical information, as well as the interplay of interests between the reporting businesses and their competitors, customers, and suppliers, the Supreme Court concluded:

- The numerical information is valuable and useful to competitors (for analyzing factory-level energy costs, technology levels, and planning improvements), and to customers and suppliers (as objectively supported material for price negotiations).

- Disclosure of this information would place these external parties in a more advantageous position in business competition or price negotiations, while conversely forcing the reporting businesses into more unfavorable conditions.

- The Court found an "objective probability" (kyakkanteki na gaizensei) that the competitive position and other legitimate interests of the reporting businesses would be harmed by such disclosure.

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the numerical information squarely falls under the category of non-disclosable information as defined in Article 5, item 2(a) of the Information Disclosure Act.

Public Interest Proviso Not Met

X had also argued, in the alternative, that even if the information fell under the exemption, it should be disclosed under the proviso to Article 5, item 2. This proviso mandates disclosure if it is deemed necessary for the protection of human life, health, livelihood, or property. The Supreme Court briefly dismissed this claim, stating that, considering the content and nature of the numerical information, it was not recognized as necessary for such protective purposes and therefore did not qualify for disclosure under the proviso.

Interpreting "Likelihood of Harm": The Key Precedent

Legal commentary accompanying the case highlights its significance as the first Supreme Court ruling specifically interpreting the corporate information exemption in Article 5, item 2(a) of the Information Disclosure Act, particularly the meaning of "likelihood of harm" (gai suru osore). A related case with nearly identical reasoning was also decided on the same day.

The legislative drafters of the Information Disclosure Act had indicated that "likelihood of harm" under this provision should be assessed comprehensively on a case-by-case basis. This assessment should consider the type and character of the corporation or business-operating individual, the nature of their rights and interests (including constitutional rights like freedom of religion or academic freedom, where applicable), and the relationship between the entity and the administration. They clarified that "likelihood" in this context implies "a legally protectable degree of probability," not merely a remote or statistical possibility.

Furthermore, an earlier Supreme Court decision (concerning a local information disclosure ordinance, not the national Act) had established that for information to be non-disclosable due to causing "clear disadvantage" to a corporation, it is insufficient that the information is merely something "one normally wouldn't want known". That ruling required a showing that disclosure would harm the corporation's competitive position or other legitimate interests, and that this harm was "objectively clear". This precedent underscored the need for an objective assessment of harm based on evidence, rather than subjective apprehensions. Prior to the 2011 ruling, lower courts generally considered both the "probability" and "objectivity" of harm when applying Article 5, item 2(a).

The 2011 Supreme Court decision aligns with and solidifies this approach. After its detailed analysis, the Court explicitly found an "objective probability" of harm. The commentary emphasizes that the Supreme Court's adoption and application of "probability" and "objectivity" as the key standards for assessing the "likelihood of harm" under Article 5, item 2(a) is the primary precedential value of this ruling, extending its relevance to other cases involving this exemption.

Critical Perspectives on the Ruling

Despite its significance, the Supreme Court's reasoning has drawn some critical observations from legal commentators:

- One point of discussion is the Court's reference to the 2005 amended Global Warming Countermeasures Act in its analysis of reports submitted for FY2003, raising questions about the appropriateness of using a subsequently amended law to contextualize the disclosure of earlier data.

- Another critique is that the Supreme Court appeared to focus on the typical or general nature of the numerical information in question. Some commentators have suggested that a more individualized assessment, considering the specific circumstances of each business operator whose data was requested, might have been warranted to determine the likelihood of harm accurately.

Regarding the public interest proviso (Art. 5, item 2, enabling disclosure for protecting life, health, etc.), X had argued for its application. The Supreme Court rejected this without extensive reasoning. Typically, applying this proviso involves a balancing act: comparing the benefits protected by disclosure against the interests protected by non-disclosure, with the former needing to outweigh the latter. It also generally requires a reasonable expectation that disclosure will concretely contribute to the protection of life, health, livelihood, or property. The Supreme Court, in this instance, seemingly assumed that the numerical information would not significantly contribute to such protective interests, or at least did not articulate a detailed balancing of these interests in its judgment, despite having thoroughly examined the interests supporting non-disclosure.

Implications for Environmental Transparency and Corporate Secrecy

The Supreme Court's 2011 decision has important implications for efforts to access corporate environmental data in Japan. By affirming the non-disclosure of detailed, factory-level energy consumption figures based on a finding of "objective probability" of harm to competitive interests, the ruling underscores the significant weight given to protecting businesses' commercial advantages, even when the information has potential environmental relevance. It highlights the challenges faced by environmental advocates and the public in obtaining granular data that could be used to assess environmental performance and hold corporations accountable for their energy use and associated impacts. The case illustrates the judiciary's role in drawing the line between the public's interest in transparency and the safeguarding of legitimate corporate interests as defined by the Information Disclosure Act.

Conclusion

The October 14, 2011, Supreme Court judgment concerning factory energy usage data provides a definitive interpretation of the corporate information exemption under Japan's Information Disclosure Act. By establishing the "objective probability of harm" as the standard for withholding such information, the Court has set a significant precedent that prioritizes the protection of companies' competitive positions and other legitimate commercial interests when faced with requests for detailed operational data. While affirming the principle that the applicability of such exemptions is a matter for objective judicial determination rather than administrative discretion, the ruling also signals the substantial hurdles that can exist in accessing specific corporate data, even when it pertains to areas of public concern like energy consumption and environmental impact. The decision continues to inform the ongoing discourse on how to appropriately balance transparency, public interest, and the protection of legitimate corporate rights in an information-driven society.