Power, Planes, and Public Duty: How Japan's Supreme Court Defined Bribery at the Highest Level

What are the official duties of a nation's prime minister? The question is vast, touching upon everything from constitutional authority to political influence. But in the context of criminal law, the answer can be critical. If a company bribes a prime minister to use their influence over a cabinet minister to secure a favorable outcome, is this an illegal act "in connection with the prime minister's duties"? Or does it fall into a "gray area" of political persuasion outside the scope of bribery law?

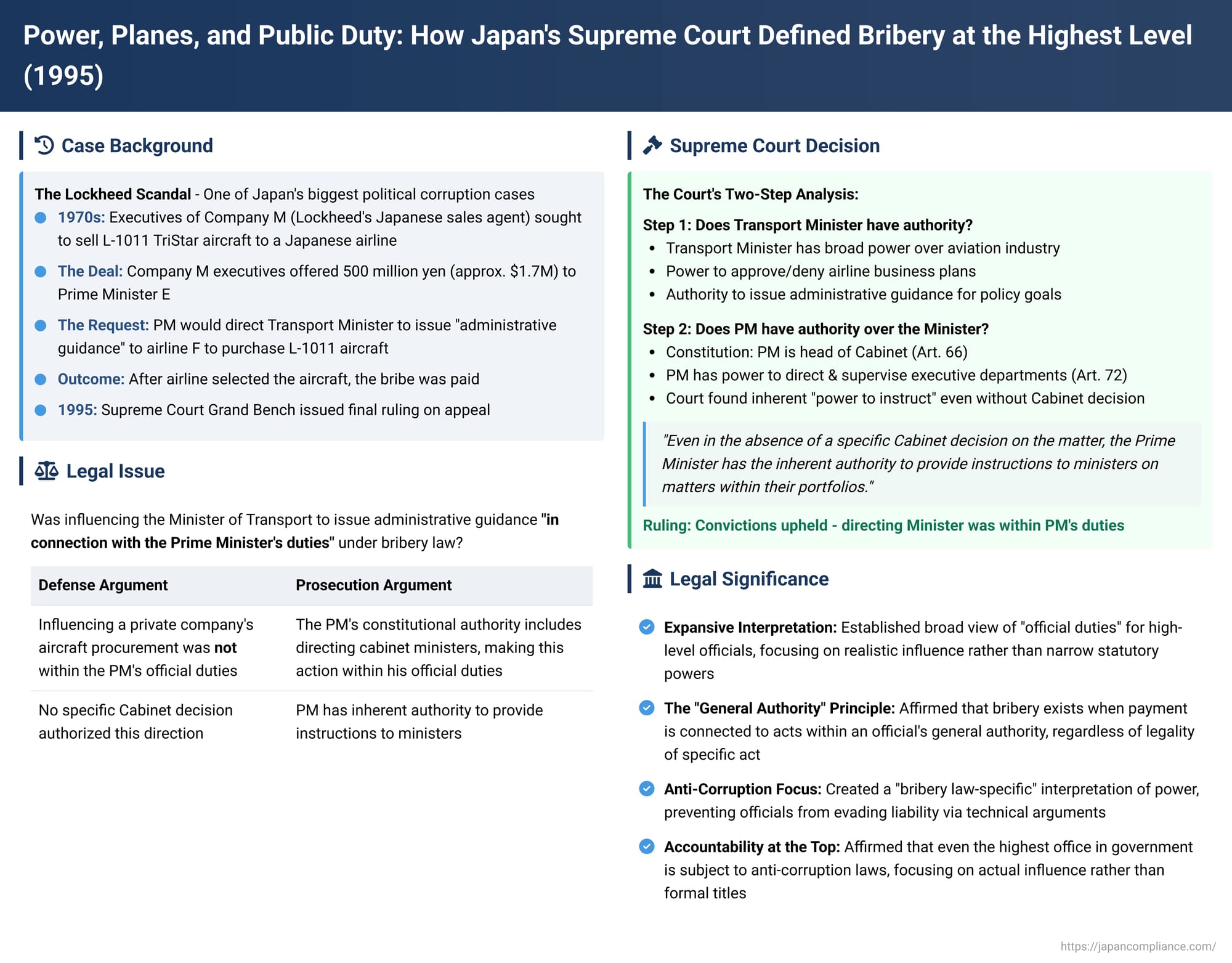

This fundamental question of power and public duty was at the center of one of the most significant legal rulings in Japan's post-war history: the Supreme Court Grand Bench decision of February 22, 1995. The judgment was the final word in the infamous Lockheed Scandal bribery trial, and in it, the Court provided an authoritative definition of the scope of a prime minister's duties for the purpose of combating corruption at the highest level of government.

The Facts: The L-1011 and the 500 Million Yen Bribe

The case was a chapter in the Lockheed Scandal, a massive political controversy that shook Japan in the 1970s.

- The Players: The defendants were executives of Company M, the Japanese sales agent for the American aerospace manufacturer, L Corporation. The public official at the center of the case was E, who was the Prime Minister of Japan at the time of the events.

- The Goal: The defendants were working to persuade a major Japanese airline, F, to purchase the L-1011 TriStar airliner, manufactured by L Corporation.

- The Bribe and the Request (Seitaku): To secure the deal, the defendants promised a bribe of 500 million yen to Prime Minister E. In exchange, they asked him to perform two key actions. The Supreme Court focused its legal analysis on the first of these:

- That Prime Minister E would direct his Minister of Transport to issue "administrative guidance" to Airline F, encouraging it to select and purchase the L-1011 aircraft.

- The Payment: After Airline F ultimately decided to purchase the L-1011, the 500 million yen bribe was paid. The defendants were charged with giving a bribe under Article 198 of the Penal Code.

The Legal Question: Was This the Prime Minister's "Duty"?

The core of the defense's argument was that influencing a private company's aircraft procurement decision was not part of the Prime Minister's official duties. They argued that since the requested favor fell outside his official authority, the payment could not legally be a bribe "in connection with his duties." The lower courts disagreed and convicted the defendants, leading to the final appeal before the Supreme Court's Grand Bench. The Supreme Court explicitly chose to base its ruling solely on the request for the Prime Minister to influence the Minister of Transport, declining to rule on the separate request for him to lobby the airline directly.

The Supreme Court's Two-Step Analysis

The Supreme Court upheld the convictions, laying out a meticulous two-step analysis to establish that the requested favor was, indeed, connected to the Prime Minister's official duties.

Step 1: Does the Minister of Transport have this authority?

The Court first had to determine if the act the Prime Minister was asked to instigate—encouraging an airline to buy a specific plane—was within the authority of the Minister of Transport.

- No Express Power: The Court acknowledged that no law explicitly grants the Minister of Transport the power to command a private airline to purchase a particular aircraft model.

- The Power of "Administrative Guidance": However, the Court affirmed the broad power of Japanese government agencies to issue "administrative guidance" (gyōsei shidō)—such as guidance, recommendations, or advice—to achieve administrative goals within their jurisdiction.

- The Minister's Broad Authority over Aviation: The Court noted that under the Ministry of Transport Establishment Act and the Civil Aeronautics Act, the Minister held vast power over the airline industry. This included the authority to license new airline routes and, crucially, to approve or deny any changes to an airline's "business plan" (jigyō keikaku). Introducing a new aircraft type requires a change to this plan, giving the Minister ultimate say based on criteria like public convenience, safety, and financial soundness.

- Conclusion for Step 1: Given this extensive approval power, the Court concluded that the Minister of Transport does have the general official authority to issue administrative guidance encouraging an airline to select a specific aircraft, particularly if there is a valid administrative purpose for doing so (e.g., if one model is deemed safer or more aligned with national transportation policy).

Step 2: Does the Prime Minister have authority over the Minister in this way?

Having established the Transport Minister's authority, the Court then addressed whether the Prime Minister had the authority to direct the Minister to use it.

- Constitutional and Legal Powers: The Court pointed to the Prime Minister's constitutional role as the head of the Cabinet (Constitution of Japan, Art. 66) with the power to direct and supervise all executive departments (Art. 72). It also referenced the Cabinet Act, which states that this direction should be "based on a policy decided in a Cabinet meeting" (Art. 6).

- The Inherent "Power to Instruct": This was the Court's most significant finding. It ruled that even in the absence of a specific, pre-existing Cabinet decision on the matter, the Prime Minister's position as the head of government gives him the inherent authority to provide "instructions" (including guidance and advice) to his ministers on how to handle matters within their portfolios. This power is necessary, the Court reasoned, to allow the government to respond effectively to fluid and diverse administrative needs, as long as the instruction does not contradict an explicit will of the Cabinet.

- Conclusion for Step 2: Therefore, the Prime Minister's act of directing the Transport Minister to issue guidance was generally within his official authority as an "instruction."

Analysis: A Broad Definition of Power for a Broad Anti-Corruption Purpose

This landmark decision affirmed an exceptionally broad view of a prime minister's official authority for the purposes of bribery law.

- The "General Authority" Principle is Key: The Court began its analysis by stating a core principle of Japanese bribery law: a bribe is illegal if it is connected to an act within the official's general official authority, regardless of whether the specific act would have been legal in that particular instance. The crime lies in the act of "selling the office" itself; paying an official to perform an illegal act is still bribery because it corrupts the public's trust in the fairness of that office.

- A "Bribery Law-Specific" Interpretation of Power?: The Court's decision to find an inherent "power to instruct" for the Prime Minister, separate from the Cabinet Law's more formal requirement of a prior Cabinet decision, has been a topic of much discussion. Some legal commentators suggest that the lower courts could have found sufficient grounds in existing general Cabinet policies. By choosing not to do so, the Supreme Court created a broader, more inherent source of authority. This can be understood as a purposive interpretation tailored to the context of bribery law. The rationale is that a powerful prime minister's influence over his cabinet is a political reality, and the law must be able to treat the corrupt selling of that influence as a crime, even if it is exercised through informal "instructions" rather than formal, cabinet-approved commands. This approach prevents a powerful official from arguing that since there was no formal Cabinet decision on a specific matter, they had no "duty" regarding it and thus could not be bribed.

Conclusion

The 1995 Grand Bench ruling in the Lockheed Scandal trial stands as the definitive statement on the scope of a prime minister's duties in bribery cases in Japan. It establishes that a prime minister's "duties" are not limited to formally executing cabinet decisions but also include the vast and powerful realm of providing instruction and guidance to cabinet ministers. The decision sends an unmistakable message that the highest office in the nation is not immune from the reach of bribery laws, and that the informal but immense power of that office cannot be sold for private gain. It defines the "duty" of a top official not by the narrow text of specific legal powers, but by the full, realistic scope of their influence over the entire machinery of government.