Power, Planes, and Payoffs: The Lockheed Scandal and the Scope of a Prime Minister's Duties

Judgment Date: February 22, 1995

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

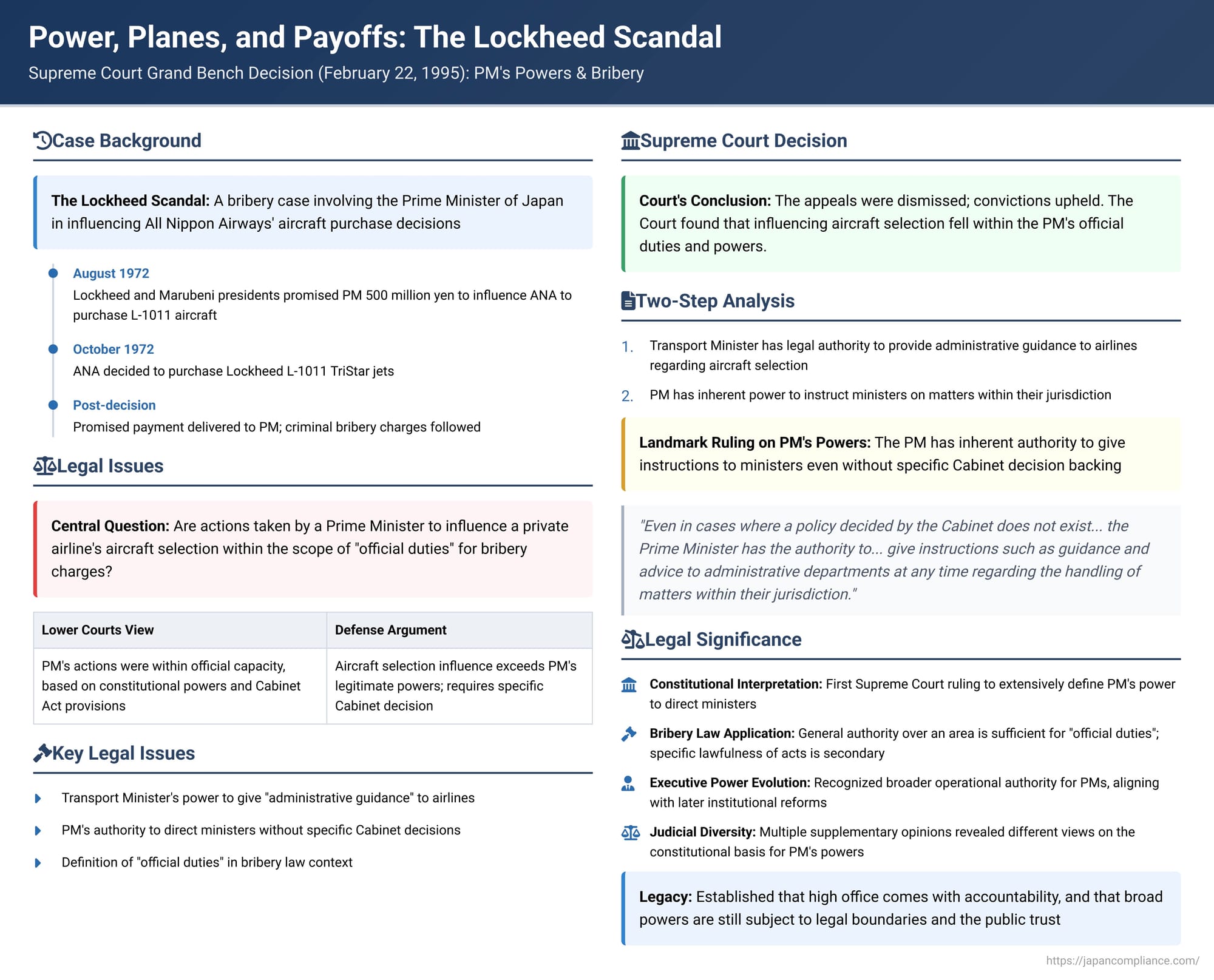

The Lockheed bribery scandal, which erupted in the 1970s, sent shockwaves through Japan's political landscape and led to a landmark 1995 Supreme Court decision. This ruling delved deep into the nature and scope of a Prime Minister's official duties and powers (shokumu kengen), particularly in the context of bribery charges. The case explored whether a Prime Minister's actions to influence a specific aircraft purchase by a private airline fell within the ambit of their official capacity, a crucial element for establishing bribery.

The Lockheed L-1011 Deal: A Prime Minister, an Airline, and a Bribe

The case revolved around efforts by the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation to sell its L-1011 TriStar passenger jets to All Nippon Airways (ANA). The facts, as established in lower courts, were that in August 1972, A, the president of Marubeni Corporation (Lockheed's sales agent in Japan), along with others, conspired with B, the president of Lockheed. They approached C, who was the Prime Minister of Japan at the time, requesting his cooperation in securing ANA's purchase of the L-1011 aircraft. A promise of 500 million yen was made to C as a success fee.

Following ANA's decision in October 1972 to purchase the L-1011s, the promised sum was indeed paid to C. This led to criminal charges, including bribery. A central legal question in the bribery trial was whether the actions C was asked to perform, and did perform, constituted acts within his official duties or powers as Prime Minister. (It should be noted that C passed away during the lengthy appeal process, and the public prosecution against him was subsequently dismissed. However, the legal principles established by the Supreme Court regarding the scope of a Prime Minister's powers, in the context of the remaining defendants' appeals, remain highly significant).

Lower Courts: Finding the PM's Actions Within Official Purview

Both the Tokyo District Court (First Instance), in its judgment on October 12, 1983, and the Tokyo High Court (Appeal Court), on July 29, 1987, found the defendants, including C (prior to his death), guilty of the charges relevant to this discussion. Their reasoning on the Prime Minister's powers included these key points:

- PM's Power of Direction: The Prime Minister's constitutional power (Article 72 of the Constitution) to direct and supervise the various administrative departments of the government, as implemented by Article 6 of the Cabinet Act, requires that such direction be based on a policy decided by the Cabinet. However, the lower courts held that a general, basic framework for such a policy would suffice; a highly specific, detailed Cabinet decision for every directive was not necessary.

- Minister of Transport's Authority: The Minister of Transport possesses the official authority to provide "administrative guidance" (gyōsei shidō) to private airline companies concerning their selection of specific aircraft models.

- PM's Influence as Official Duty: Given the Minister of Transport's authority, the Prime Minister, in turn, has the power to direct and supervise the Minister of Transport to issue such administrative guidance. This is because the content of the Prime Minister's direction (i.e., influencing aircraft selection) falls within the legitimate scope of the competent minister's (the Minister of Transport's) powers.

- Direct Approach as Related Act: Furthermore, any direct efforts by the Prime Minister to influence ANA's decision were considered acts closely related to his official duties.

The defendants appealed these rulings to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench Ruling: Affirming PM's Powers

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench dismissed the appeals of the remaining defendants relevant to the bribery charges, thereby upholding their convictions. In doing so, the Court provided a detailed exposition on the scope of a Prime Minister's official powers.

I. Bribery and Official Duties: A General Principle

The Court began by affirming a general principle in bribery law:

- The crime of bribery aims to protect the fairness of public duties and the public's trust in those duties.

- For an act to be the quid pro quo for a bribe, it is sufficient that the act generally falls within the public official's statutory official duties or powers.

- Whether the public official could have lawfully performed that specific act under the concrete circumstances of the case is not the determining factor for bribery. The receipt of money or benefit in exchange for performing such a generally authorized act, in itself, undermines public trust.

II. Two-Step Analysis for PM's Influence on a Minister

Regarding the Prime Minister's specific actions in this case—influencing the Minister of Transport to recommend that ANA purchase Lockheed aircraft—the Court laid out a two-step test to determine if these actions fell within the PM's official powers:

- The Minister of Transport's act of recommending to ANA the selection and purchase of a specific aircraft model must itself be within the Minister of Transport's official duties and powers.

- The Prime Minister's act of influencing the Minister of Transport to make such a recommendation must be within the Prime Minister's official duties and powers.

III. Minister of Transport's Power of Administrative Guidance

The Court affirmed the first condition:

- Administrative agencies generally have the authority, within the scope of their legally defined mission and jurisdiction, to offer guidance, recommendations, advice, etc., to specific persons or entities to achieve certain administrative objectives. Such "administrative guidance" is considered an official act stemming from the public official's duties and powers.

- Considering the then-existing Ministry of Transport Establishment Act (which tasked the Ministry with overseeing aviation) and the Aviation Act (which gave the Minister powers regarding airline licensing and approval of operational plans, including aircraft types), the Court concluded that the Minister of Transport's act of providing administrative guidance to ANA to recommend the purchase of specific aircraft models "falls within the Minister of Transport's official powers." The Court reasoned that such a recommendation could be a legitimate exercise of administrative guidance, for instance, if a particular aircraft model was deemed most suitable based on safety standards or route requirements, thus facilitating the smooth administration of aviation laws. Whether such guidance was actually appropriate or lawful in the specific instance was secondary to the general power existing.

IV. Prime Minister's Inherent Power to "Instruct" Ministers

The Court then turned to the second condition—the Prime Minister's power to influence the Minister of Transport. This was the most debated aspect:

- PM's Constitutional Role: The Constitution establishes the Prime Minister as the head of the Cabinet, which collectively exercises executive power (Article 66). The PM has the power to appoint and dismiss Ministers of State (Article 68) and the authority to, "representing the Cabinet, exercise control and supervision over various administrative branches" (Article 72). This places the PM in a paramount position to lead the Cabinet and coordinate the various administrative departments.

- Cabinet Act Provisions: The Cabinet Act further specifies that the PM presides over Cabinet meetings (Article 4), directs and supervises administrative departments "based on policies decided by the Cabinet" (Article 6), and can suspend the dispositions or orders of administrative departments pending Cabinet action (Article 8).

PM's Power Beyond Specific Cabinet Decisions: The Court acknowledged that Article 6 of the Cabinet Act links the PM's power of direction and supervision to "policies decided by the Cabinet." However, the majority opinion then made a crucial assertion:

"Even in cases where a policy decided by the Cabinet does not exist, considering the Prime Minister's aforementioned status and powers, in order to respond without delay to fluid and diverse administrative needs, the Prime Minister has the authority to, at least as long as it does not contradict the explicit will of the Cabinet, give instructions such as guidance and advice to administrative departments at any time regarding the handling of matters within their jurisdiction. This is to be considered appropriate."

This "Court Opinion" (法廷意見 - hōtei iken, or majority opinion) thus recognized an inherent power of the Prime Minister to issue "instructions" (指示 - shiji)— encompassing guidance and advice—to ministers even without a specific, pre-existing Cabinet decision directly authorizing that particular instruction.

A Spectrum of Judicial Views: The Supplementary Opinions

While the Grand Bench was unanimous in dismissing the appeals, various justices issued supplementary opinions or, in one instance, a distinct "opinion," revealing different nuances in their legal reasoning, particularly concerning the basis and scope of the Prime Minister's power to direct ministers:

- Supplementary Opinion ① (Justices Sonobe, Ohno, Chigusa, Kawai): Argued that the Prime Minister's power of direction and supervision under Constitution Article 72 is inherent and not created by Cabinet decisions. However, for this power to have compulsory legal effect upon a minister, Article 6 of the Cabinet Act requires the backing of a policy decided by the Cabinet. This opinion distinguishes between general guidance and legally binding directives.

- Supplementary Opinion ② (Justices Kabe, Onishi, Ono): Stated that, for the purpose of determining bribery, the High Court's original reasoning—which affirmed the Prime Minister's official powers based on Constitution Article 72 and Cabinet Act Article 6 (implying a broad interpretation of what constitutes a "policy decided by the Cabinet")—was also acceptable.

- Supplementary Opinion ③ (Justice Ozaki): Agreed that the Prime Minister's power of direction and supervision is granted by Constitution Article 72. When this power is exercised in accordance with Cabinet Act Article 6 (i.e., based on a Cabinet decision), it carries compulsory force.

- Opinion ④ (Justices Kusaba, Nakajima, Miyoshi, Takahashi H.): This group found that no specific Cabinet policy existed that could serve as a basis for the Prime Minister's direction in this particular instance under Cabinet Act Art. 6. However, they still found the Prime Minister's actions relevant for bribery. They reasoned that the Minister of Transport's administrative guidance to an airline is "an act closely related to the Minister of Transport's duties." Consequently, the Prime Minister giving instructions to the Minister of Transport regarding such an act is "an act closely related to the duties the Prime Minister inherently possesses." This approach relies on the established "closely related acts" doctrine in bribery law, rather than finding direct official power for the specific instruction.

Unpacking the Decision: Defining the Scope of Top Executive Power

This landmark judgment was the first time the Supreme Court extensively deliberated on the Prime Minister's official powers, especially the authority to direct individual ministers.

The "Closely Related Acts" Doctrine in Bribery:

In Japanese bribery law, a public official can be held liable not only for acts falling squarely within their formally defined duties but also for "acts closely related to their official duties" (shokumu missetsu kanren kōi). This doctrine recognizes that officials can exert influence even in areas not strictly within their direct authority. The High Court and Opinion ④ in the Supreme Court invoked this concept. The Supreme Court's main "Court Opinion" (and Supplementary Opinions ①, ②, ③), however, found it unnecessary to rely on this doctrine for the Prime Minister's influence over the Minister of Transport, as they located a more direct basis for the PM's general power to instruct.

The PM's Constitutional vs. Statutory Powers of Direction:

A central legal debate before this ruling was the relationship between the Prime Minister's broad supervisory power mentioned in Constitution Article 72 and the more specific wording of Cabinet Act Article 6, which requires direction to be "based on policies decided by the Cabinet."

- Traditional/Prevailing View (Pre-judgment): While acknowledging the PM's enhanced status under the post-war Constitution (no longer merely "first among equals" as under the Meiji Constitution), this view generally held that the PM's direction under Article 72 was exercised "representing the Cabinet." Thus, it was not a purely personal power of the PM but one rooted in the Cabinet's collective will, with Cabinet Act Article 6 seen as concretizing this principle.

- Minority View (Adopted by Court Opinion): Some scholars had argued that the PM's position as "head" of the Cabinet (Constitution Article 66) or the PM's power to dismiss other Ministers of State (Constitution Article 68) implicitly granted a more independent authority to issue "instructions" or guidance to ministers, even without a specific prior Cabinet resolution for each instance.

The Supreme Court's "Court Opinion" effectively adopted this minority view. It recognized the practical reality that Prime Ministers frequently issue directives and guidance to ministers without a formal Cabinet decision backing every such instruction. This interpretation grants the Prime Minister a constitutionally derived operational authority to instruct, while arguably limiting the scope of Cabinet Act Article 6 (requiring a Cabinet decision) to situations where more coercive or formally binding direction is intended.

The Evolving Understanding of Cabinet Governance:

Legal commentators have noted that the distinction between "coercive" direction (supposedly backed by a Cabinet decision) and non-coercive "instructions" might be more about the degree of political weight and factual influence than a clear difference in direct legal enforceability against a minister. Ultimately, a Prime Minister's strongest tool to ensure a minister's compliance is the power of dismissal.

Since this judgment, reforms in Japan's central government (e.g., strengthening the Cabinet Secretariat and Cabinet Office's coordination functions, establishing the Cabinet Bureau of Personnel Affairs) have institutionally enhanced the Prime Minister's ability to lead and coordinate. The "instruction" power recognized by the Supreme Court can be seen as fitting within this evolving model of stronger prime ministerial leadership. However, if such non-Cabinet-based instructions are considered to have constitutional and administrative legal validity (beyond just satisfying the general "official power" element for bribery), it raises questions about the need for appropriate legal control mechanisms, such as requirements for documentation and transparency of such instructions.

The Supreme Court's methodology—deriving a minister's official powers for bribery purposes from their ministry's organizational statutes, and the Prime Minister's powers from a combination of constitutional role, organizational statutes, and inherent directive authority—has influenced subsequent bribery cases involving other Ministers of State.

Conclusion: Implications for Political Accountability and the Definition of Official Duty

The 1995 Supreme Court decision in the Lockheed scandal case provided a pivotal interpretation of the Prime Minister's official powers. By recognizing a broad authority for the Prime Minister to "instruct" ministers even without specific, itemized Cabinet decisions for each such instruction, the Court acknowledged the operational realities of executive leadership. For the purposes of bribery law, this meant that a Prime Minister soliciting or accepting benefits in exchange for exercising such influence over a minister regarding matters within that minister's general competence could be held criminally liable. The ruling affirmed that the highest office in the land is not above the law and that its powers, however broad, come with accountability, especially concerning the public trust inherent in official duties. The varied opinions among the justices also highlighted the ongoing legal and constitutional dialogue about the precise balance of power within the Japanese Cabinet system.