Power, Pay, and Process: Key Japanese Labor Law Decisions in 2024

TL;DR

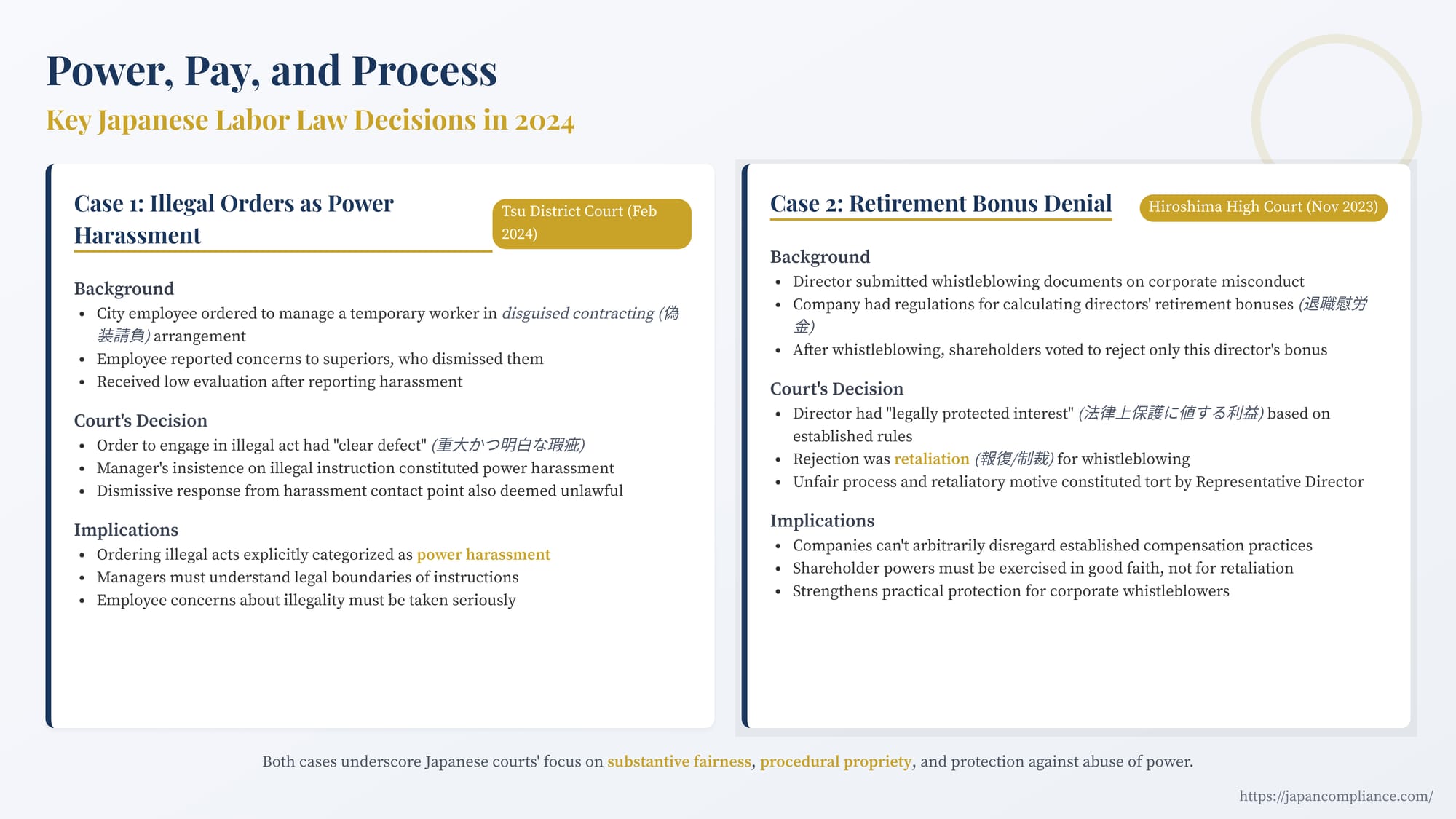

- A February 2024 Ōtsu District Court case held that ordering an employee to break the Worker-Dispatch Act is power harassment, awarding damages.

- A November 2023 Hiroshima High Court case deemed a retaliatory denial of a director’s retirement bonus unlawful, awarding the bonus as tort damages.

- Together the rulings stress that Japanese courts protect employees and directors from illegal orders and bad-faith retaliation; compliance processes and fair governance are essential.

Table of Contents

- Case 1: Ordering Illegal Acts as Power Harassment (Ōtsu District Court, Feb 2 2024)

- Case 2: Retaliation for Whistleblowing and Retirement Bonus Denial (Hiroshima High Court, Nov 17 2023)

- Conclusion

Staying abreast of labor law developments is essential for businesses operating in Japan. Recent court rulings offer valuable insights into how Japanese courts are interpreting employee rights, employer responsibilities, and corporate governance in the employment context. This post examines two noteworthy decisions from late 2023 and early 2024: one addressing power harassment involving illegal work orders, and another concerning director liability for the rejection of a retirement bonus payment.

Case 1: Ordering Illegal Acts as Power Harassment (Ōtsu District Court, Feb. 2, 2024)

This case (Ōtsu Chihō Saibansho, February 2, 2024) involved a public servant but illuminates principles applicable to private workplaces regarding illegal instructions and power harassment (pawā harasumento or pawahara).

Background:

A city employee (the plaintiff) was assigned to a new role where his predecessors had been involved in directly managing a temporary worker hired by an external association (the "Association") to which the city had outsourced a specific project. This arrangement raised concerns about being an illegal "disguised contract" (gisō ukeoi), where the city was effectively dispatching the worker in violation of the Worker Dispatch Act (労働者派遣法, Rōdōsha Haken Hō).

The plaintiff voiced these concerns to his superior, Manager A, who dismissed them and explicitly ordered the plaintiff to directly instruct and manage the Association's temporary worker (Worker C), stating, "You, Deputy Counselor X, will teach [Worker C] everything," and "The Lifelong Learning Division is the secretariat. You, Deputy Counselor X, an employee of the Lifelong Learning Division, will do it. You will instruct C."

The plaintiff reported this situation as harassment to another superior, Officer B, who served as a harassment contact point. Officer B acknowledged the arrangement was improper ("Everything you do is disguised contracting... The manager probably knows") but stated it was a necessary "transition period" for the fiscal year and made dismissive remarks, including implying the plaintiff should quit if he couldn't comply ("If you're prepared to quit, you can do anything"). Subsequently, the plaintiff received unusually low performance evaluations and was transferred. He sued the city for damages, alleging, among other things, that the orders constituted power harassment.

The Court's Decision:

The Ōtsu District Court found the superiors' actions constituted unlawful power harassment leading to damages under the State Redress Act (which applies to public entities but reflects tort principles).

- Illegality of the Order: The court first analyzed the duty of public servants to obey orders (Local Public Service Act, Art. 32). Citing precedent, it noted this duty applies unless the order has a "grave and clear defect" (jūdai katsu meihaku na kashi). The court found that ordering the plaintiff to directly supervise Worker C was an instruction to violate the Worker Dispatch Act (by engaging in disguised contracting). This illegality constituted a "clear defect," and compliance would lead to an unlawful situation. Therefore, the order itself was unlawful, and the plaintiff had no duty to obey it.

- Harassment Finding: Manager A's insistence on the plaintiff carrying out the illegal instruction, leveraging his position of authority, was deemed power harassment. Similarly, Officer B's dismissive comments, made against the backdrop of the power imbalance and exceeding the scope of necessary work communication, were also found to be unlawful harassment.

- Outcome: The court partially granted the plaintiff's claim for damages based on the harassment. (Notably, the court did not find the subsequent low performance evaluations or the transfer to be unlawful in themselves, treating them as separate issues based on the specific facts presented).

Analysis and Implications:

This decision is significant because it explicitly categorizes ordering an employee to perform an illegal act as a form of power harassment. While Japanese law, particularly following amendments to the Labor Measures Comprehensive Promotion Act (労働施策総合推進法, Rōdō Shisaku Sōgō Suishin Hō), mandates employers prevent power harassment (generally defined by leveraging workplace superiority to cause mental or physical distress beyond the necessary scope of work), this ruling clarifies that instructions compelling illegal conduct fall under this umbrella.

- Disguised Contracting (Gisō Ukeoi): The underlying issue of gisō ukeoi is crucial. It occurs when a company outsources work via a contract for services but then directs and controls the contractor's employees as if they were dispatched workers or direct employees, violating the Worker Dispatch Act. This is a compliance risk for companies utilizing contractors or outsourcing arrangements; they must ensure they do not exercise direct command authority over the contractor's staff.

- Managerial Responsibility: The case underscores that managers cannot hide behind "necessity" or "transition periods" to justify ordering illegal actions. Employers have a duty to ensure managers understand legal boundaries and provide lawful instructions.

- Handling Employee Concerns: The dismissive response by Officer B, despite being the designated harassment contact, highlights the importance of taking employee concerns about potential illegality seriously and investigating them appropriately, rather than pressuring compliance.

Case 2: Retaliation for Whistleblowing and Retirement Bonus Denial (Hiroshima High Court, Nov. 17, 2023)

This case (Hiroshima Kōtō Saibansho, November 17, 2023) dealt with the denial of a retirement bonus and established that interfering with a director's legitimate expectation of such a bonus can constitute a tort, especially when motivated by retaliation.

Background:

A director (the plaintiff, X) of a broadcasting company retired at the end of his term. The company had internal regulations (kitei) specifying the calculation method for directors' retirement bonuses (taishoku irōkin). The board initially resolved to propose the payment of X's bonus, calculated according to the regulations, at the upcoming general shareholders' meeting.

Before the meeting, however, X submitted documents to the Representative Director (Y2) alleging past corporate misconduct (essentially acting as a whistleblower, kokuhastu). Y2 did not substantively respond or investigate.

At the shareholders' meeting chaired by Y2, a motion was introduced by another executive to consider X's bonus separately from other retiring directors. Votes controlled by Y2 and affiliated insiders were then used to reject the payment of X's bonus specifically.

X sued the company and Y2, claiming the rejection was unlawful retaliation and seeking damages equal to the bonus amount plus costs. X argued Y2 committed a tort (under Company Act Art. 429(1) - director liability to third parties, or Civil Code Art. 709 - general tort) and the company was vicariously liable (Company Act Art. 350 or Civil Code Art. 715). The District Court dismissed the claim, finding shareholder resolutions are generally discretionary.

The High Court's Decision:

The Hiroshima High Court reversed the lower court's decision, finding Y2 and the company liable.

- Legally Protected Interest: The court acknowledged that retirement bonuses for directors generally require shareholder approval (under Company Act Art. 361) and are not an automatic right simply based on internal rules. However, it held that when a company has clear, established internal regulations for calculating such bonuses, a retiring director develops a "legally protected interest" (hōritsu jō hogo ni atai suru rieki) in the expectation of receiving that bonus.

- Tortious Infringement: While shareholders can reject a bonus proposal, doing so can become unlawful under "special circumstances" (tokudan no jijō) where the rejection illegally infringes the director's protected interest.

- Retaliation as Special Circumstance: The court found such circumstances existed here. X's whistleblowing was not proven to be a breach of his duties. Y2 and other insiders ignored the allegations, failed to give X a chance to be heard, and engineered the rejection at the shareholders' meeting without substantive deliberation. The High Court concluded this sequence of events constituted retaliation (hōfuku) or punishment (seisai) for X's whistleblowing. This retaliatory motive and the unfair process used to deny the bonus unlawfully infringed X's legally protected interest.

- Liability: Y2's orchestration of the rejection was deemed a tort. The company was held vicariously liable for the actions of its representative director. The court awarded damages equivalent to the calculated bonus plus attorney fees.

Analysis and Implications:

This ruling provides important clarifications regarding director compensation and shareholder meeting conduct.

- Retirement Bonuses (Taishoku Irōkin): These are common in Japan but legally complex. Typically treated as remuneration, their payment requires specific authorization (usually shareholder resolution) beyond just internal company rules. This case doesn't change that fundamental requirement but creates a pathway to liability if a rejection is improperly motivated or procedurally unfair when clear internal rules exist.

- Legitimate Expectations: The concept of a "legally protected interest" arising from established internal rules, even without prior shareholder approval for the specific payment, is significant. It suggests companies cannot arbitrarily disregard their own established compensation practices for departing directors, especially if the denial appears retaliatory.

- Process and Motive Matter: The decision emphasizes that even actions within the formal power of shareholders (like voting down a proposal) can be unlawful if executed in bad faith, for retaliatory purposes, or through unfair procedures that stifle deliberation. This aligns with broader principles of good faith and prevention of abuse of rights.

- Whistleblower Protection: While not strictly a whistleblower protection law case, the finding that retaliation for internal reporting constituted a tort strengthens the practical protection for directors and employees who raise concerns about corporate misconduct.

Conclusion

These two cases, while dealing with different specific issues – power harassment via illegal orders and director liability for bonus denial – both underscore the Japanese courts' increasing focus on substantive fairness, procedural propriety, and the protection of employee and director rights against arbitrary or abusive conduct by those in positions of power. They highlight the importance for companies in Japan to ensure not only formal compliance with labor and corporate laws but also adherence to principles of good faith, fair process, and respect for legitimate expectations created by internal rules and practices. Failure to do so can lead to significant legal liability.

- Job-Scope Agreements & Employee Transfers in Japan: When Contract Limits Override Employer Flexibility

- Shunto vs. Japan’s Minimum Wage System: Navigating Dual Wage-Setting Mechanisms

- Director Liability and Corporate Donations in Japan: Balancing Philanthropy and Fiduciary Duty

- MHLW Power Harassment Prevention Portal (Japanese)

- FSA Corporate Governance Code – 2021 Revision (PDF)