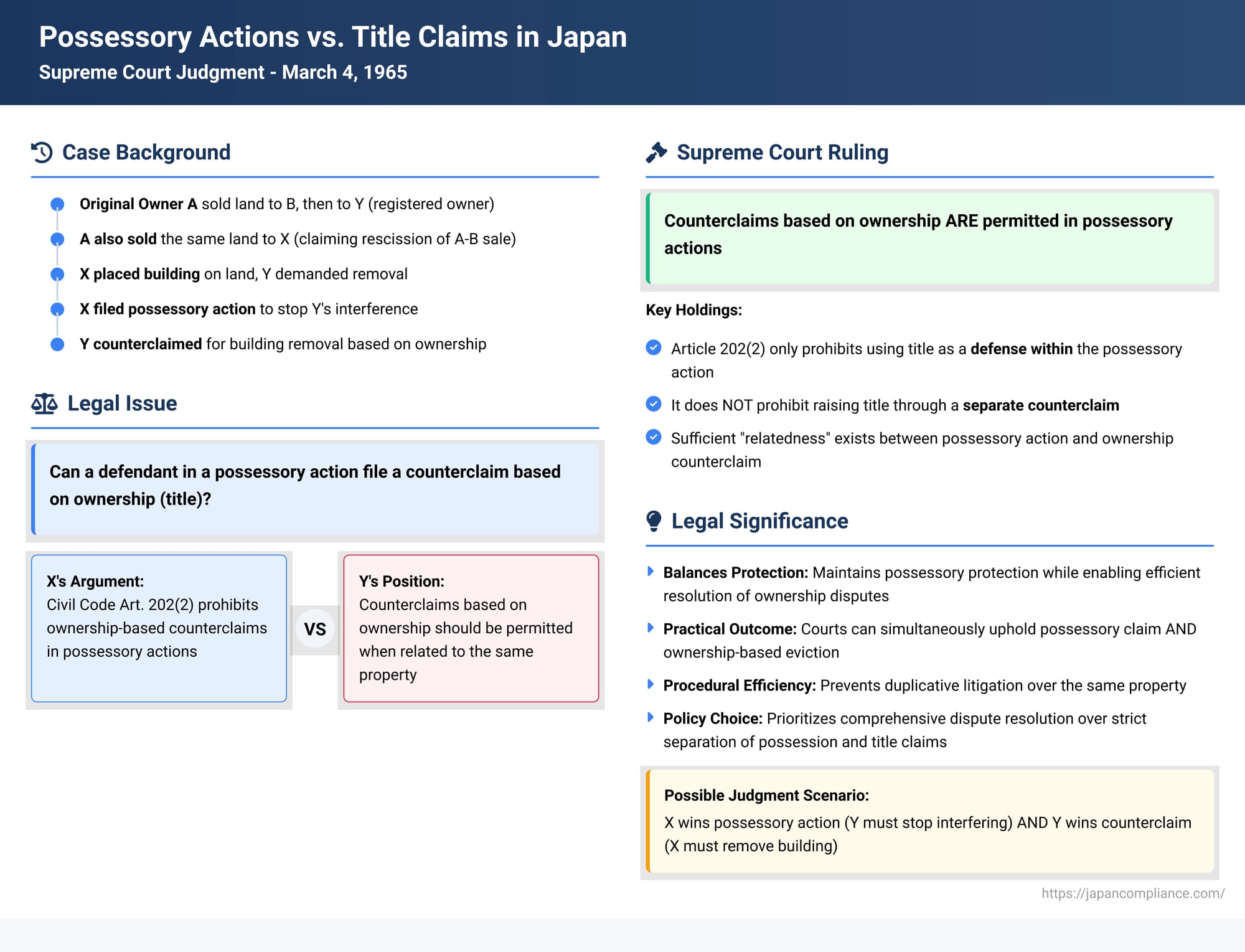

Possessory Actions vs. Title Claims in Japan: Can a Landowner Counterclaim for Eviction in a Possession Suit?

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of March 4, 1965 (Showa 40) (Case No. 654 (O) of 1963 (Showa 38))

Subject Matter: Main Claim for Maintenance of Possession and Counterclaim for Building Removal and Land Vacation (占有保持請求本訴ならびに建物収去土地明渡請求反訴事件 - Sen'yū Hoji Seikyū Honsō narabi ni Tatemono Shūkyo Tochi Akewatashi Seikyū Hanso Jiken)

Introduction

This article examines a 1965 Japanese Supreme Court judgment that addresses an important procedural intersection between possessory actions and claims based on underlying legal title. Specifically, the case clarifies whether a defendant, when sued in a possessory action (占有の訴え - sen'yū no uttae) – for instance, a claim for the maintenance of possession – can file a counterclaim (反訴 - hanso) seeking remedies such as building removal and land vacation based on their assertion of ownership (a superior underlying title, or 本権 - honken). The Supreme Court affirmed that such counterclaims are permissible, drawing a distinction between using underlying title as a defense within the possessory action itself (which is restricted) and raising it as a separate but related counterclaim.

The dispute involved X (appellant/plaintiff in the main possessory action) and Y (appellee/defendant in the main action and plaintiff in the counterclaim based on ownership).

Factual Background

The land in question was originally owned by A. A sold it to B, who then sold it to Y. An ownership transfer registration was completed directly from A to Y (an intermediate-omitted registration). Separately, A also purportedly agreed to rescind the A-B sales contract and then sold and delivered the same land to X. X subsequently moved her own building onto the Land and was undertaking repair work when Y interfered, demanding the removal of the building.

X filed a lawsuit (the main claim) based on her right of possession of the Land, seeking a judgment that Y must not interfere with X's possession. In response, Y filed a counterclaim against X. Y's counterclaim was based on Y's registered ownership of the Land, seeking an order for X to remove X's building from the Land and vacate the premises.

The lower courts (first instance and appellate) ultimately found that the alleged rescission of the A-B contract was not proven or could not be asserted against Y, and that Y's registered ownership took precedence over X's claim derived from the subsequent purchase from A. The appellate court, interpreting X's main claim as an action for preservation of possession (占有保全の訴え - sen'yū hozen no uttae under Article 199 of the Civil Code), found that there was a risk of Y interfering with X's possession and thus upheld X's main claim. Simultaneously, it fully upheld Y's counterclaim based on ownership, ordering X to remove the building and vacate the land.

X appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other things, that allowing a counterclaim based on underlying title (ownership) in response to a purely possessory action lacked the necessary "relatedness" (牽連性 - kenrensei, a requirement for counterclaims under the old Code of Civil Procedure, similar to current requirements) and violated Article 202, paragraph 2 of the Civil Code. This article stipulates that "a possessory action shall not be decided on the basis of reasons relating to the underlying title." X contended that adjudicating Y's ownership-based counterclaim within the same proceedings as X's possessory claim was legally impermissible.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, affirming the lower court's approach to the counterclaim.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Interpretation of Article 202, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code:

The Court clarified that Article 202, paragraph 2, prohibits the court from deciding a possessory action based on reasons related to the underlying title. This means that a defendant in a possessory action cannot use their underlying title (e.g., ownership) as a defense to defeat the plaintiff's possessory claim itself. Possessory actions are decided based on the facts of possession and its disturbance, separate from the ultimate question of who has the superior legal title. - Counterclaims Based on Underlying Title are Permissible:

However, the Court stated that this provision does not prohibit a defendant in a possessory action from filing a counterclaim based on their underlying title. The restriction in Article 202(2) applies to defenses within the possessory claim, not to separate, albeit related, counterclaims. - Relatedness (牽連性 - Kenrensei) of the Claims:

The Court then considered whether Y's counterclaim (for building removal and land vacation based on ownership) was sufficiently related to X's main claim (for non-interference with possession of the same land) to be permissible as a counterclaim. It concluded that when comparing Y's counterclaim with X's main possessory action, it cannot be said that relatedness is lacking. Both claims ultimately concern the right to use and occupy the same piece of land, stemming from the same factual dispute between the parties.

Therefore, the Supreme Court found no error in the appellate court's decision to allow and adjudicate Y's counterclaim based on ownership within the same proceedings as X's possessory action. The appeal was dismissed.

Analysis and Implications

This 1965 Supreme Court judgment is a significant decision clarifying the procedural relationship between possessory actions and actions based on underlying title in Japanese civil procedure.

- Separation of Possession and Title (in Principle): The core idea behind possessory actions (占有の訴え - sen'yū no uttae) is to provide a relatively quick and straightforward remedy to protect the factual state of possession, irrespective of who holds the ultimate legal title (本権 - honken). Article 202(2) of the Civil Code upholds this separation by preventing defenses based on underlying title from derailing the possessory claim itself. This is intended to maintain peace and order by preventing self-help and requiring disputes over title to be resolved in separate proceedings focused on title.

- Counterclaims as a Procedural Tool: However, this judgment confirms that the separation principle does not go so far as to bar a defendant from raising their own claims based on underlying title via a counterclaim in the same lawsuit. A counterclaim allows for the efficient resolution of related disputes between the same parties in a single proceeding.

- "Relatedness" Requirement for Counterclaims: The Court affirmed that the counterclaim based on ownership was sufficiently related to the possessory claim regarding the same property. This is generally accepted, as both claims stem from the conflict over who has the right to control and use the land. Resolving both together can prevent piecemeal litigation.

- Practical Effect:

- A plaintiff can succeed in their possessory action (e.g., to stop interference or recover possession) if they prove the elements of that claim, even if the defendant has superior underlying title. The defendant cannot simply argue "I'm the owner, so your possession claim fails" as a defense to the possessory claim.

- However, if the defendant (who claims to be the true owner) files a counterclaim based on their ownership, and proves their ownership, they can obtain a judgment for remedies like eviction against the plaintiff.

- This can lead to a situation where the court might issue a judgment upholding the plaintiff's possessory claim (e.g., ordering the defendant to stop interfering) and simultaneously upholding the defendant's counterclaim based on ownership (e.g., ordering the plaintiff to vacate the land and remove their building). This was the outcome in the appellate court in this case, which the Supreme Court did not disturb on this procedural ground.

- Efficiency vs. Purity of Possessory Protection:

The PDF commentary accompanying this case notes that this ruling was the first Supreme Court decision to explicitly address the permissibility of such counterclaims, and it aligned with what was becoming the majority view among scholars and some lower courts.- Arguments for Permitting Counterclaims: Focus on judicial economy and preventing contradictory judgments or repetitive litigation. If the defendant truly is the owner, it makes sense to resolve the entire dispute at once.

- Arguments Against (or for Limiting) Counterclaims in Possessory Actions (the "違法説 - ihōsetsu" - illegality theory, mentioned in PDF): Emphasize the unique purpose of possessory actions to provide swift protection to factual possession and deter self-help. Allowing counterclaims based on title might bog down the possessory aspect with complex title disputes, undermining its speed and simplicity. Proponents of this view might argue that the defendant should file a separate lawsuit for their title-based claims.

- Procedural Mechanisms for Managing Combined Claims: The PDF commentary also touches upon procedural tools that courts can use even if such counterclaims are allowed, such as restricting or separating oral arguments (Civil Procedure Act Art. 152) or issuing a partial judgment on the possessory claim first (Art. 243(3)). This could potentially preserve some of the speed and focus of the possessory action while still allowing for the eventual resolution of the title dispute. The extent to which these are (or should be) used is a matter of judicial discretion and ongoing discussion.

This Supreme Court judgment establishes that while the underlying title cannot be used as a direct defense within a possessory action, it can form the basis of a counterclaim if the claims are related. This approach seeks to balance the special nature of possessory protection with the goals of procedural efficiency and comprehensive dispute resolution. It affirms that Japan's modern civil procedure, unlike some historical systems, does not have a completely separate, expedited track for possessory actions that would entirely exclude simultaneous consideration of title if raised by counterclaim.