Political Strikes in Japan: The Y Corporation Case – Supreme Court, September 25, 1992

Case Reference: Disciplinary Action Invalidity Confirmation Claim

Court: Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench

Judgment Date: September 25, 1992

Case Number: (O) No. 1310 of 1992

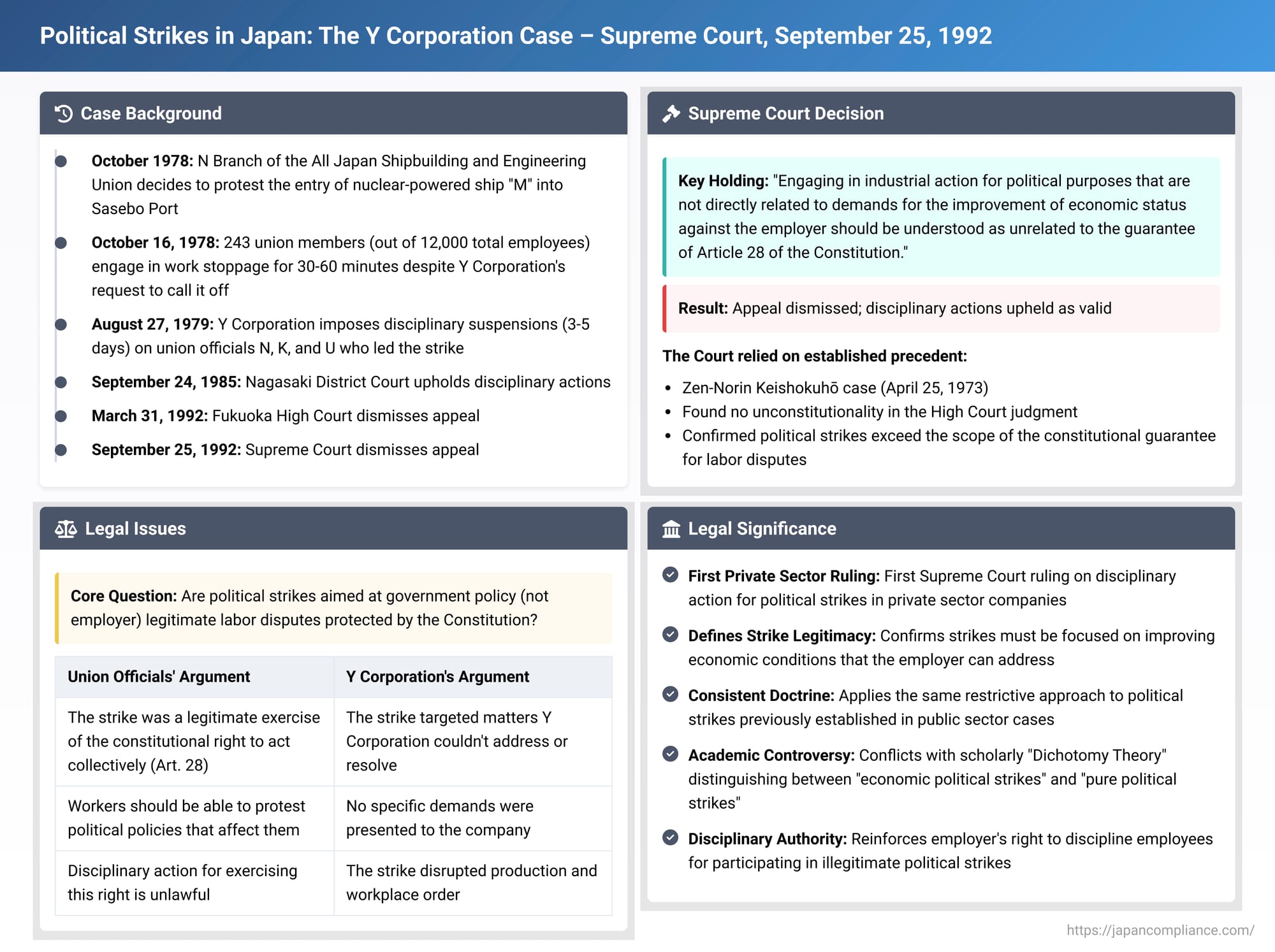

This blog post examines a significant ruling by the Japanese Supreme Court concerning the legality of "political strikes" undertaken by employees in the private sector and the validity of subsequent disciplinary actions by the employer. The case, commonly referred to as the Y Corporation, Nagasaki Shipyard case, provides crucial insight into how Japanese labor law treats industrial action aimed at political objectives rather than direct demands against the employer.

I. The Factual Matrix

The dispute originated from a short-term work stoppage at one of Y Corporation's major shipyards. The plaintiffs, Mr. N, Mr. K, and Mr. U (the appellants before the Supreme Court), were employees of Y Corporation (the respondent) and held leadership positions (Chairman, Vice-Chairman, and Secretary-General, respectively) within the N Shipyard Branch of the All Japan Shipbuilding and Engineering Union (hereinafter referred to as "N Branch").

In October 1978, the N Branch, aligning with the policy of the Nagasaki Prefectural Labor Union Council, decided to protest the entry of the nuclear-powered ship "M" into Sasebo Port. This protest also targeted the broader policies of the national government, Nagasaki Prefecture, and Sasebo City concerning the ship and related facilities.

Following a strike authorization vote among its members, the N Branch leadership, including Messrs. N, K, and U, directed 243 union members to engage in a work stoppage. This occurred on October 16, 1978, with employees leaving their workplaces for periods ranging from 30 minutes to one hour, starting from 4:30 PM. This action was taken despite Y Corporation's formal request to call off the strike. At the time, Y Corporation employed approximately 12,000 individuals in total, with the striking workers representing a small fraction of the workforce.

Nearly a year later, on August 27, 1979, Y Corporation imposed disciplinary sanctions on Messrs. N, K, and U. The company characterized the work stoppage as an illegal strike. Its rationale was that the strike concerned matters that the company itself could not address or resolve, and for which no specific demands had been presented to the company. Y Corporation deemed such a strike "unacceptable for the continuation of production and the maintenance of workplace order." Consequently, Mr. N, Mr. K, and Mr. U received suspensions from work, ranging from three to five days, for their roles in instigating and leading the strike.

The three union officials challenged the disciplinary measures, filing a lawsuit to confirm the invalidity of the sanctions. They argued that the strike was a legitimate exercise of the right to engage in industrial action and, therefore, the disciplinary measures were unlawful.

II. The Journey Through the Courts: Lower Court Decisions

The case progressed through the Japanese judicial system, with both the District Court and the High Court ruling in favor of Y Corporation.

- Nagasaki District Court (September 24, 1985): The first instance court upheld the validity of the disciplinary actions. It reasoned that a strike whose direct target is a state institution or state power, aiming to influence legislative or administrative trends, or to express protest, pertains to matters that an employer cannot legally or factually resolve. Such a strike, the court found, cannot be considered an exercise of the right to dispute conducted in the context of achieving objectives through collective bargaining with the employer. Therefore, it falls outside the scope of protection afforded by Article 28 of the Japanese Constitution (which guarantees the right of workers to organize, bargain, and act collectively) and does not constitute a legitimate industrial action.

- Fukuoka High Court (March 31, 1992): The plaintiffs appealed to the Fukuoka High Court, which also dismissed their appeal. The High Court concurred that the strike concerned matters not directly related to the working conditions of Mr. N, Mr. K, and Mr. U. It further stated that demanding collective bargaining with Y Corporation on such issues was out of the question, as was any expectation that Y Corporation could exercise influence over the political matters at hand.

Dissatisfied with the High Court's decision, the union officials escalated the case to the Supreme Court of Japan.

III. The Supreme Court's Stance

On September 25, 1992, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court delivered its judgment, dismissing the appeal lodged by Messrs. N, K, and U. The Supreme Court's reasoning was concise, primarily affirming the lower courts' decisions and relying on established precedent.

The Court stated: "Engaging in industrial action for political purposes that are not directly related to demands for the improvement of economic status against the employer should be understood as unrelated to the guarantee of Article 28 of the Constitution. This is in accordance with the precedent of this Court (Supreme Court Grand Bench judgment of April 25, 1973, in the Zen-Norin Keishokuhō case). The judgment of the court below, which is to the same effect, can be affirmed as correct, and the original judgment does not contain the unconstitutionality alleged by the appellants."

The Supreme Court found no errors in the High Court's fact-finding or legal application. Thus, the disciplinary actions taken by Y Corporation against the union officials were ultimately deemed valid.

IV. Understanding "Political Strikes" in Japanese Labor Law

The Y Corporation case is a pivotal decision regarding political strikes in the private sector. To appreciate its implications, it's essential to understand the concept of political strikes within the framework of Japanese labor law.

- Definition: A "political strike" is generally defined as an industrial action where the demands or protests are directed not at the employer (the counterparty in a labor-management relationship) but at governmental or state bodies in a broad sense. These can include the national government (and even foreign governments), the Diet (parliament), courts, or local public entities. While the term "strike" is used, it can encompass various forms of dispute tactics, such as picketing.

- Legitimacy of Industrial Action: Under Japanese labor law, the legitimacy of any industrial action is a critical factor. It is typically assessed based on three main aspects:If an industrial action is deemed "legitimate" (seitō), it enjoys certain protections. These include immunity from criminal liability (Article 1, Paragraph 2 of the Trade Union Act) and civil liability (i.e., claims for damages by the employer, Article 8 of the Trade Union Act). Furthermore, disciplinary action by an employer against employees for participating in a legitimate strike can constitute an unfair labor practice (Article 7 of the Trade Union Act). The "purpose" of the strike is a particularly crucial element, as it often defines the boundaries of the constitutionally guaranteed right to engage in industrial action. Political strikes, by their nature, directly challenge these boundaries.

- Purpose: The objectives the action seeks to achieve.

- Manner/Form (Taiyō): The methods and tactics employed.

- Procedure: The steps taken before initiating the action (e.g., strike votes).

- Significance of the Y Corporation Ruling: This judgment was the first instance where the Supreme Court directly addressed the validity of disciplinary measures imposed on union officials for leading a political strike within a private-sector company. The ruling demonstrated a consistent application of the Supreme Court's previously established views on political strikes, which had largely been developed in cases involving public sector employees.

V. Judicial Precedents and Trends

The Y Corporation decision did not emerge in a vacuum. It aligns with a broader, albeit not voluminous, body of case law concerning political strikes.

- Civil Cases:

- Historically, many political strikes have not resulted in legal disputes.

- In the All Japan Harbor Transport Workers' Union Nagoya Branch Case (Nagoya District Court, October 21, 1968; Nagoya High Court, April 10, 1971), a strike protesting the ratification of the treaty between Japan and South Korea, which involved refusal of overtime, led to the dismissal of union officials. The courts upheld these dismissals, with one judgment noting the strike lacked legitimacy "at least in relation to the employer," which some commentators suggest might imply that criminal immunity was not necessarily negated.

- A contrasting outcome was seen in the Seventy-Seventh Bank Case (Sendai District Court, May 29, 1970). Here, union officials were dismissed for participating in a strike against a proposed bill aimed at preventing political violence, which the union feared would infringe upon the right to organize. The court invalidated the dismissals, reasoning that actions necessary for the improvement of workers' social and economic status could be legitimate objectives for collective action, even if the specific aim of the union's protest did not constitute a direct matter for collective bargaining with the bank.

- In the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Hiroshima Precision Machinery Works Case (Hiroshima District Court, January 24, 1979), a short-duration strike protesting the US-Japan Security Treaty and the company's involvement in arms manufacturing was at issue. Disciplinary suspensions imposed on union leaders were upheld. The court reasoned that the company's arms manufacturing activities were not matters for negotiation with the local union branch.

- It is also common in civil cases dealing with dismissals or disciplinary actions arising from strikes that, irrespective of the strike's overall legitimacy, courts will examine whether the employer's exercise of disciplinary power constituted an abuse of rights (Labor Contract Act, Article 15) or if a dismissal lacked objectively reasonable grounds (Labor Contract Act, Article 16).

- Criminal Cases and Public Sector Precedents:

- While not directly applicable to private-sector disciplinary matters, criminal cases and public-sector precedents have shaped the Supreme Court's general stance on political strikes.

- The Kansai Electric Power Kyoto Branch Case (Kyoto District Court, February 14, 1957) suggested that if the primary aim of an industrial action is the improvement of working conditions, the presence of secondary, related political demands does not automatically render the action illegitimate.

- The Japanese National Railways (JNR) Higashi-Sanjo Station Case (Niigata District Court, October 26, 1964) posited that a political strike deemed illegal under labor law might still be considered lawful under criminal law in certain circumstances.

- The Supreme Court, particularly in cases involving public servants, has consistently held that industrial actions for political purposes lack legitimacy.

- In the Zentei Chuyu Case (All Japan Postal Workers' Union Central Post Office Case, Supreme Court Grand Bench, October 26, 1966), concerning charges under the Postal Act for disrupting mail services through politically motivated workplace rallies, the Court stated that industrial actions conducted for political purposes, rather than for the objectives stipulated in Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the Trade Union Act (i.e., maintaining and improving working conditions and raising economic status), exceed the legitimate bounds of Article 28 of the Constitution and are not immune from criminal sanctions.

- The Zenshiho Anpo Rokujuyon Case (All Japan Judiciary Employees' Union 1964 Security Treaty Case, Supreme Court Grand Bench, April 2, 1969), involved court employees participating in workplace rallies against the revised US-Japan Security Treaty. The Court found that political strikes by court employee organizations "deviate from the legitimate scope" and, even if brief and non-violent, pose a risk of disrupting duties and causing significant harm to public life.

- The Zen-Norin Keishokuhō Case (All Japan Agriculture and Forestry Ministry Workers' Union Police Duties Bill Case, Supreme Court Grand Bench, April 25, 1973), cited in the Y Corporation judgment, involved Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry employees who encouraged participation in workplace rallies protesting a proposed amendment to the Police Duties Execution Act. The Court ruled that public servants are inherently prohibited from engaging in industrial action by law (the National Public Service Act), and therefore, striking for political purposes is "impermissible in a dual sense."

VI. Diverging Perspectives: Judicial Doctrine vs. Academic Theories

The Supreme Court's approach in the Y Corporation case reflects a long-standing judicial tendency to deny legitimacy to political strikes, especially when their primary purpose is not directly tied to negotiable terms and conditions of employment. This judicial stance, however, is not universally shared, particularly within academic circles where various theories on the scope of the right to strike have been developed.

- The "Illegitimacy Theory" (Predominant Judicial View):

This theory, generally followed by Japanese courts including in the Y Corporation decision, posits that the right to engage in industrial action (dispute rights) is fundamentally linked to the process of collective bargaining. Its constitutional guarantee (Article 28) is seen as a means to empower workers to achieve a more equal footing with employers in negotiating their economic conditions. Strikes are legitimate when they serve as leverage within this bargaining framework.

Under this view, political issues that cannot be resolved or influenced by the employer through collective bargaining fall outside the intended scope of protected industrial action. As stated by some proponents, it is not considered appropriate for workers to be granted a superior right to strike over political matters—a right not available to ordinary citizens or other social groups—especially when such strikes impose burdens on employers who are essentially innocent bystanders with no power to address the political demands. This latter point is sometimes critiqued by opponents as the "sobazue-ron" (literally, "whacking the bystander" argument), questioning the fairness of allowing employers to suffer damages due to political protests directed elsewhere.

It's worth noting that even among scholars who generally support this restrictive view, some argue that if political demands are merely secondary or incidental to primary economic demands against the employer, the industrial action might still warrant protection. However, distinguishing between primary and secondary purposes can be practically challenging. - The "Legitimacy Theory" (Various Academic Stances):

A contrasting set of theories argues for a broader interpretation of the right to strike, potentially encompassing certain political strikes.- A minority view within this camp asserts that all political strikes, including those with purely political aims (such as protesting the Security Treaty), should be considered legitimate exercises of fundamental rights.

- The Political Strike Dichotomy Theory (Futatsu-wake-ron): This is reportedly the majority view among legal scholars in Japan. It differentiates between two types of political strikes:

- "Economic Political Strikes" (Keizaiteki Seiji Sutoraiki): These are strikes where the demands or protests relate to governmental policies that directly impact the economic interests of workers, such as policies on working conditions, wages, social security, or labor legislation. Proponents argue that such strikes are protected under Article 28 of the Constitution because they are ultimately aimed at improving workers' economic and social status, which is the core purpose of trade union activity.

- "Pure Political Strikes" (Junsu Siji Sutoraiki): These involve demands or protests on broader civic or political issues that do not have a direct bearing on workers' economic interests (e.g., foreign policy, peace movements). According to the dichotomy theory, these strikes are not protected by Article 28 but may find protection under Article 21 of the Constitution, which guarantees freedom of expression, assembly, and association. There is further debate among scholars regarding the precise legal effects and immunities (e.g., from civil liability or disciplinary action) that would attach to a "pure political strike" if it were protected under Article 21.

VII. Industrial Relations Context

The debate over political strikes in Japan is also influenced by the country's unique industrial relations landscape.

- Japanese labor law and industrial relations scholarship historically developed with reference to models in Western industrialized nations. However, Japanese labor-management practices have evolved along distinct paths, characterized by features such as enterprise-based unionism (where unions are typically organized at the company level rather than by industry or craft), the relative integration of blue-collar and white-collar workers within these unions, the prevalence of company-specific wage and promotion systems often linked to merit and seniority, and robust labor-management consultation systems.

- In an environment dominated by enterprise unions, demands concerning matters beyond the individual employer's capacity to resolve are often seen as less fitting or effective. Conversely, if industrial unions (which are less common as primary bargaining units in Japan) were the main negotiating entities, demands targeting broader industry-wide or national policies might be more conceivable.

- Thus, prevailing perceptions about the nature of labor transactions and the typical bargaining unit structure (enterprise-level vs. broader levels) inevitably color the interpretation of legitimate strike purposes.

- While enterprise-based unionism has its critics and proponents, there is a recognized need for ongoing theoretical refinement concerning the legal assessment of political strikes, informed by contemporary empirical research on both Japanese and international industrial relations.

VIII. Concluding Observations

The Supreme Court's decision in the Y Corporation case solidified the prevailing judicial view in Japan that political strikes undertaken by private-sector employees, where the objectives are not directly tied to improving their economic standing vis-à-vis their employer, fall outside the protective ambit of Article 28 of the Constitution. Consequently, participants in such strikes may not be shielded from disciplinary action by their employers.

This ruling underscores a cautious approach by the Japanese judiciary towards extending the scope of protected industrial action into the political realm, particularly when it imposes burdens on employers who have no direct control over the issues being protested. While academic debate continues to explore broader conceptualizations of workers' rights to collective action, the Y Corporation case remains a key reference point illustrating the more restrictive interpretation currently upheld by Japan's highest court for private-sector political strikes.