Policy Loans by Impersonators: 1997 Japanese Supreme Court on Insurer Liability and 'Apparent Authority'

Date of Judgment: April 24, 1997

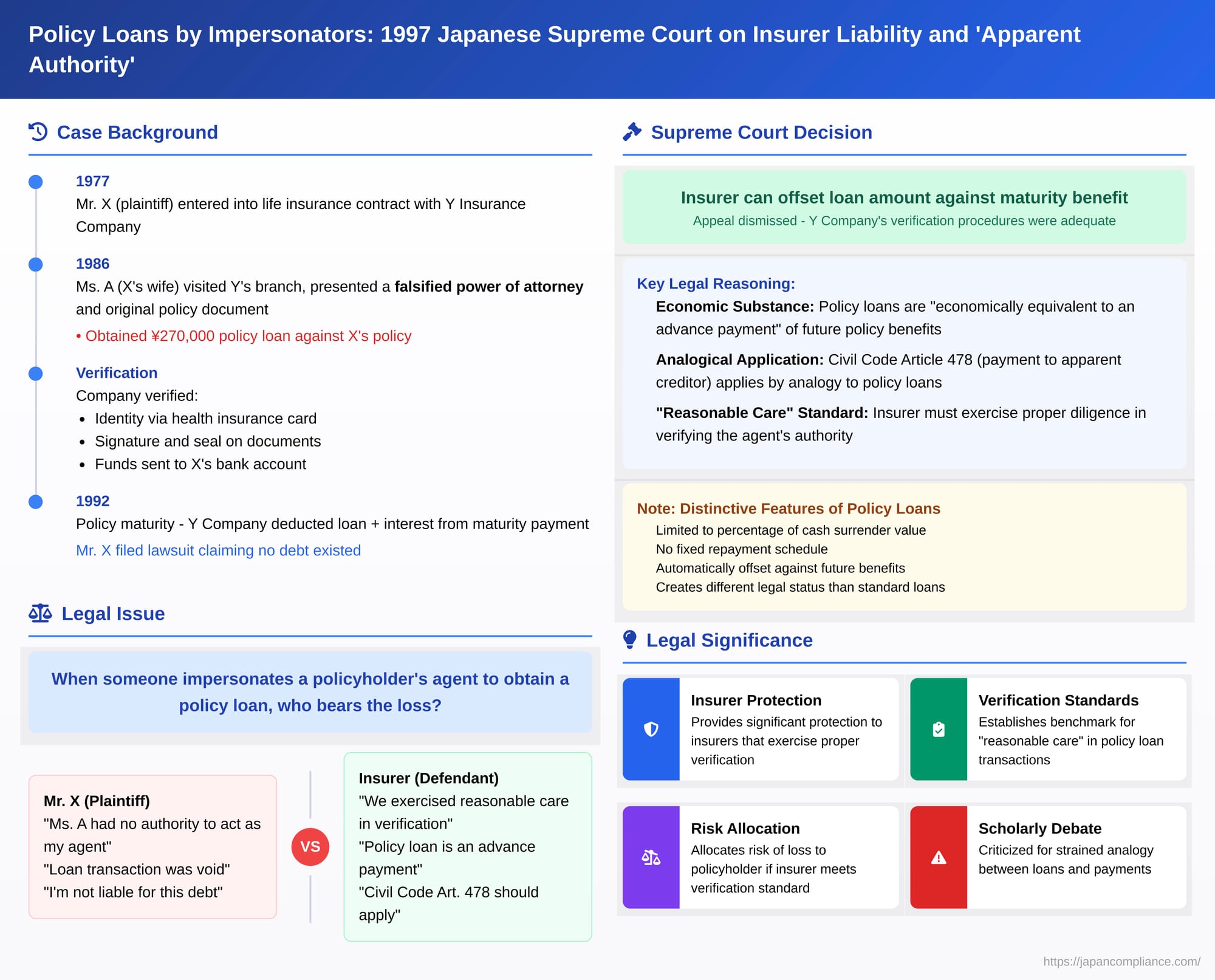

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Case No. 1951 (o) of 1993 (Action for Confirmation of Non-Existence of Debt)

Policy loans (契約者貸付 - keiyakusha kashitsuke) are a common feature of many life insurance contracts, allowing policyholders to borrow funds against their policy's accumulated cash surrender value (CSV). This provides a convenient source of liquidity. However, this convenience can be exploited. What happens if an unauthorized person, perhaps a family member impersonating the policyholder or falsely claiming to be their agent, fraudulently obtains such a loan? Who bears the loss—the duped insurer or the unsuspecting policyholder whose policy is now encumbered by an unauthorized debt? This question was central to a key decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on April 24, 1997.

The Deception: Facts of the Case

In 1977, Mr. X (the plaintiff and appellant) entered into a life insurance contract with Y Insurance Company (the defendant and respondent). Mr. X was both the policyholder and the insured, with an insurance amount of 8 million yen. His then-wife, Ms. A, was designated as the death beneficiary. Article 20, paragraph 1, of the policy terms stipulated that the policyholder could receive a "policy loan" from Y Insurance Company for an amount up to 90% of the policy's cash surrender value. It further provided that the principal and interest of any such loan would be offset against any insurance benefits (like death or maturity benefits) or cash surrender value paid out in the future.

In 1986, Ms. A, Mr. X's wife, visited a branch office of Y Insurance Company. Claiming to be acting as Mr. X's agent, she applied for and received a policy loan of approximately 270,000 yen. She subsequently spent most of these funds on living expenses and other personal costs. To facilitate this transaction, Ms. A had presented several documents to the insurer:

- A power of attorney form, ostensibly completed and signed in Mr. X's name.

- The original insurance policy document for Mr. X's contract.

- A personal seal (inkan) that was either identical or very similar to the seal Mr. X had used on his original policy application documents.

The employee of Y Insurance Company handling the transaction performed several verification steps. The employee confirmed Ms. A's identity as Mr. X's wife by checking her health insurance card. The employee also compared the signature purportedly of Mr. X on the power of attorney and the seal impression thereon with Mr. X's signature and seal impression on file from the original policy application, finding them to be consistent. Furthermore, the employee confirmed that the bank account designated for the deposit of the loan proceeds was indeed an account held in Mr. X's name. Based on these checks, Y Insurance Company's representative believed that Ms. A possessed the proper authority to act as Mr. X's agent and proceeded to disburse the loan.

Years later, in 1992, Mr. X's life insurance policy reached its maturity date. Y Insurance Company sent Mr. X a notice stating that the maturity benefit payable to him would be the total matured amount minus the outstanding principal and accrued interest of the policy loan taken out by Ms. A. Mr. X contested this. He argued that Ms. A's act of borrowing the funds was an unauthorized act by a non-agent and was therefore void as far as he was concerned. He subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y Insurance Company, seeking a legal declaration that no debt existed on his part with respect to this policy loan.

The Tokyo District Court, in the first instance, dismissed Mr. X's claim. It found that the circumstances supported the application of Civil Code Article 110, which deals with "apparent agency" (where a third party is led to believe someone has authority, even if they don't, due to the principal's conduct). However, on appeal, the Tokyo High Court took a different path. It denied the applicability of apparent agency, finding that Ms. A lacked the requisite "basic authority" from X that is usually a precondition for apparent agency. Despite this, the High Court still ruled against X. It reasoned that the policy loan, in its essence, could be viewed as a partial advance payment of the future insurance benefits or cash surrender value. On this basis, the High Court applied Article 478 of the Civil Code by analogy. Article 478 (in its then-current form) protected a debtor who, in good faith and without negligence, made a payment to a "quasi-possessor of a claim" (債権の準占有者 - saiken no jun-senyūsha)—that is, someone who outwardly appeared to be the rightful creditor or their authorized representative, even if they were not. The High Court held that Y Insurance Company, by analogy, could assert the validity of the loan repayment (via offset) against Mr. X. Mr. X then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, arguing primarily that a loan transaction could not be equated to a payment for the purposes of applying Article 478.

The Legal Conundrum: Unauthorized Loan and Insurer's Due Diligence

The central legal issue was whether an insurer, having disbursed a policy loan to someone who fraudulently purported to be the policyholder's agent, could nevertheless hold the actual policyholder liable for that loan if the insurer had exercised a certain degree of care in verifying the purported agent's authority. This involved considering the unique nature of policy loans and their relationship to general principles of agency and payment.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Insurer Protected by Analogical Application of Art. 478

The Supreme Court dismissed Mr. X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's conclusion that Y Insurance Company could offset the loan amount. The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Economic Substance over Form: The Court acknowledged the specific nature of the policy loan system as defined in the insurance contract: loans are granted as a performance of an obligation under the policy terms, the loan amount is limited by a percentage of the cash surrender value, and the principal and interest are ultimately offset against future policy payouts (like maturity benefits, death benefits, or the CSV itself). Considering these features, the Supreme Court stated that such a policy loan, "in its economic substance, can be deemed equivalent to an advance payment of the insurance money or cash surrender value."

- Analogical Application of Civil Code Article 478: Building on this "economic equivalence," the Court held that if an insurance company, operating under such a policy loan system, disburses a loan based on an application from a person claiming to be the policyholder's agent, the principles of Civil Code Article 478 can be applied by analogy.

- Condition for Insurer Protection – "Reasonable Care": The crucial condition for the insurer to be protected under this analogical application is that the insurer must have "exercised reasonable care (相当の注意義務 - sōtō no chūi gimu) in recognizing that person as the policyholder's agent." If the insurer fulfilled this duty of care (essentially acting in good faith and without negligence in believing the purported agent had authority), then it could assert the validity of the loan against the actual policyholder.

Since the High Court had found, as a matter of fact, that Y Insurance Company had exercised such reasonable care in verifying Ms. A's apparent authority, the Supreme Court concluded that the High Court's judgment was correct and affirmed it. This meant the loan was considered validly made in respect to X, and Y could offset the outstanding loan amount from the maturity benefit.

Unpacking "Policy Loan as Advance Payment" and the Art. 478 Analogy

The Supreme Court's characterization of the policy loan as "economically equivalent to an advance payment" was a key step in its reasoning, allowing it to bridge the gap to Civil Code Article 478, which deals with payments.

Legal Nature of Policy Loans:

The legal nature of policy loans has been a subject of debate among scholars. Theories include:

- Loan for Consumption (shōhi taishaku): This view, particularly in the form of a "loan for consumption with a set-off agreement" (sōsai yoyaku-tsuki shōhi taishaku), has been a majority opinion and is reportedly the basis upon which the insurance industry operates. It sees the transaction as a true loan, with an agreement that it will be offset against future policy proceeds.

- Advance Payment (maebarai): This theory views the funds provided not as a loan but as an early payment of a portion of the benefits the policyholder is already entitled to (e.g., the CSV).

- Hybrid or Sui Generis: Some argue that policy loans don't fit neatly into either category and should be interpreted based on the specific issue at hand.

The "loan for consumption" theory sometimes struggles to explain the typical lack of fixed repayment deadlines for policy loans. Conversely, the pure "advance payment" theory has difficulty rationalizing why interest is charged on what is essentially an early receipt of one's own money. The Supreme Court in this case did not definitively adopt the advance payment theory for all purposes but used the concept of "economic equivalence" specifically to justify the analogy to Article 478. Legal commentary suggests that interest on such "advances" could be justified as a fee for the insurer's risk and the administrative cost of providing funds immediately, rather than at a future contingent date.

Why the Analogy to Article 478?

Civil Code Article 478 (old version) protected a debtor who made a payment to a "quasi-possessor of a claim" if the debtor acted in good faith and without negligence. Applying this directly to a loan transaction is problematic because a loan creates a new debt, whereas a payment discharges an existing one. By framing the policy loan's "economic substance" as an advance payment, the Court made the analogy to Article 478 more tenable. This approach had precedents in lower court decisions concerning bank loans made against deposit accounts.

The "Reasonable Care" Standard:

The determination of whether the insurer exercised "reasonable care" is a factual one. It involves assessing the adequacy of the insurer's procedures for verifying the identity of the applicant and their authority to act for the policyholder. In this case, Y Insurance Company's actions—confirming Ms. A's identity as Mr. X's wife through her health insurance card, comparing the signature and seal on the power of attorney with those on file from Mr. X's original application, and ensuring the loan proceeds were directed to Mr. X's own bank account—were deemed by the lower courts to meet this standard. Subsequent case law has also considered similar verification steps, such as checking driver's licenses and印鑑登録証明書 (inkan tōroku shōmeisho - seal registration certificates), in assessing an insurer's due diligence.

Scholarly Reactions and Ongoing Debates

The Supreme Court's use of an analogy to Article 478 in a loan context has drawn criticism from some legal scholars, who argue that the distinction between a loan and a payment is fundamental and that the analogy is strained. They contend that these are distinct types of legal acts with different prerequisites and consequences.

However, the Court's emphasis on "economic substance" over strict legal form can be seen as a pragmatic approach aimed at achieving a fair outcome in a situation involving fraud. It recognized that policy loans, with their unique link to the CSV and automatic offset against future benefits, function differently from standard commercial loans. The decision effectively allocates the risk of loss due to such impersonation: if the insurer meets its duty of care in verification, the policyholder may bear the loss; if the insurer is negligent, it likely would.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1997 decision provides a significant measure of protection to insurance companies in Japan that disburse policy loans based on fraudulent representations of agency, provided they adhere to diligent verification procedures. By characterizing the economic substance of such policy loans as akin to advance payments of future benefits, the Court was able to apply by analogy the protective principles of Civil Code Article 478, which shield those who make payments in good faith and without negligence to apparent (but not actual) rights holders. This ruling highlights the judiciary's efforts to find practical and equitable solutions in complex cases of fraud, balancing the property rights of the insured policyholder against the operational realities faced by insurers and their duty to exercise reasonable care in transactions. It underscores the importance for financial institutions to maintain robust identity and authority verification processes.