Poison Pills in Japan: Supreme Court Upholds Discriminatory Share Rights as Takeover Defense

Judgment Date: August 7, 2007

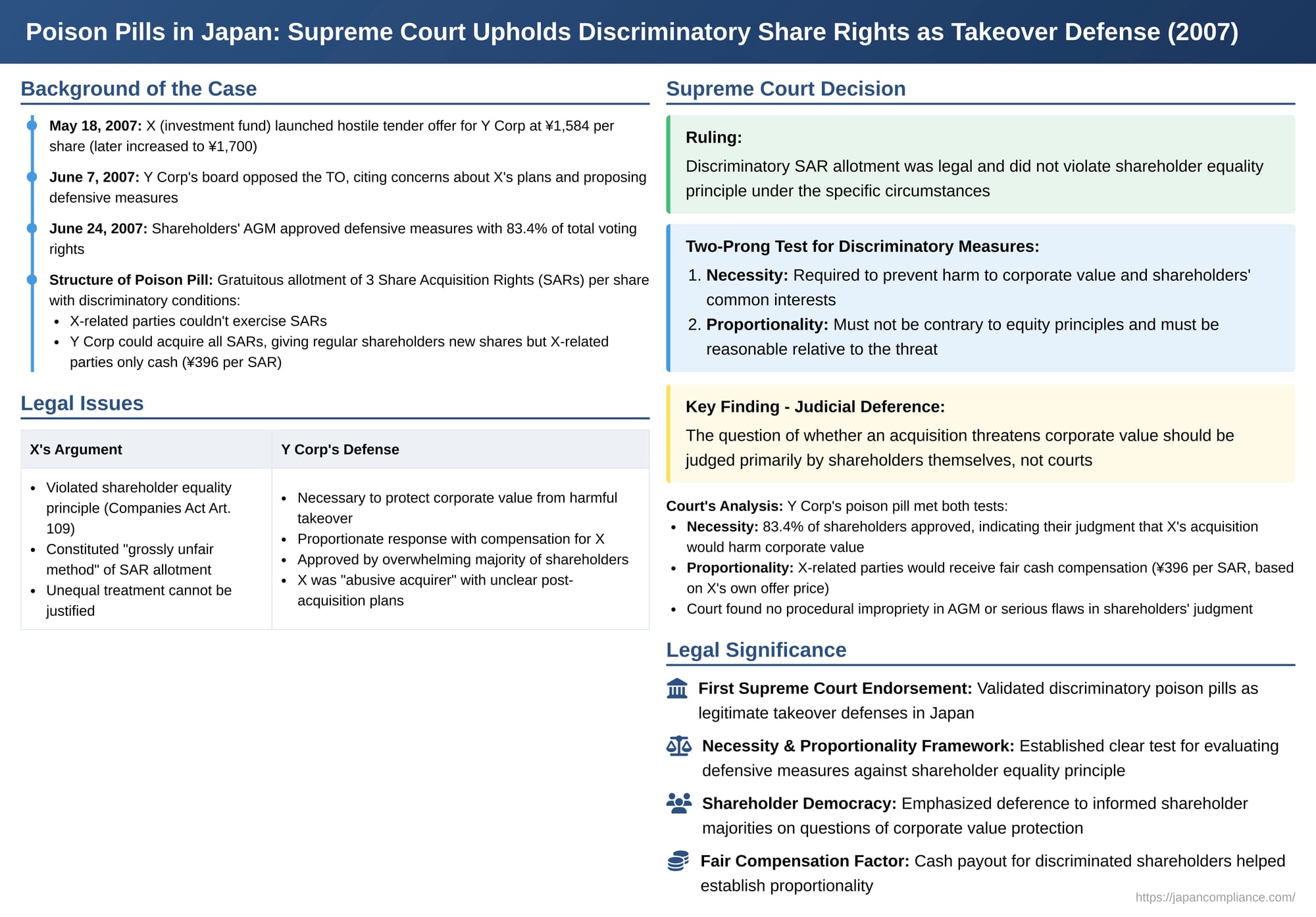

Hostile takeovers and the defensive measures companies employ to thwart them are complex areas of corporate law globally. In Japan, a landmark 2007 Supreme Court decision, often referred to in connection with Bull-Dog Sauce Co. (though we will use anonymized names here), provided significant clarification on the legality of a specific type of "poison pill" – a gratuitous allotment of share acquisition rights (SARs) with discriminatory conditions designed to dilute the hostile bidder's stake. The case grappled with fundamental principles of shareholder equality and the extent to which a company, with shareholder approval, can selectively disadvantage a perceived corporate raider.

The Hostile Tender Offer and the Target's Response

The dispute involved Y Corp, a publicly traded Japanese company, and X, an investment fund specializing in Japanese corporate investments. As of May 18, 2007, X, together with its affiliates, held approximately 10.25% of Y Corp's issued shares. A LLC, a U.S. limited liability company wholly owned by X and established for the purpose of acquiring shares on X's behalf, was the entity that launched the takeover bid.

- The Tender Offer: On May 18, 2007, A LLC announced a public tender offer (the "TO") with the objective of acquiring all outstanding shares of Y Corp. The initial offer price was ¥1,584 per share, which was later increased to ¥1,700 per share with an extended offer period.

- Target's Concerns: Y Corp's board of directors, upon reviewing the TO, expressed concerns. After submitting a list of questions to A LLC and receiving responses, Y Corp's board found A LLC's (and by extension, X's) plans lacking in clarity. Specifically, A LLC's responses indicated that X had no prior experience managing companies in Japan and no current intention to manage Y Corp directly. Furthermore, there was no concrete proposal on how Y Corp's corporate value would be enhanced post-acquisition, nor a clear policy regarding the recovery of X's invested capital.

- Board's Opposition and Defensive Proposal: Consequently, on June 7, 2007, Y Corp's board concluded that the TO, if successful, would be detrimental to Y Corp's corporate value and would harm the common interests of its shareholders. The board resolved to oppose the TO. More significantly, it decided to propose a series of defensive measures to its upcoming annual general shareholders' meeting (AGM) scheduled for June 24, 2007. These measures included:

- An amendment to Y Corp's Articles of Incorporation to stipulate that any gratuitous allotment of SARs containing certain discriminatory conditions would require approval by a special resolution of the shareholders' meeting.

- Contingent upon the approval of this amendment, a specific resolution for the gratuitous allotment of SARs with such discriminatory features – the "poison pill" itself.

The Poison Pill Mechanism

At the AGM on June 24, 2007, both the Articles of Incorporation amendment and the conditional SAR allotment (the "Allotment") were approved by a significant majority: approximately 88.7% of the votes cast by shareholders present and approximately 83.4% of Y Corp's total voting rights.

The approved Allotment of SARs (referred to as "the Share Acquisition Rights") was structured as follows:

- Allotment: On a specified record date (July 10, 2007), all shareholders listed on Y Corp's shareholder register would receive three Share Acquisition Rights for each share of Y Corp stock they held. This allotment was to be gratuitous (without payment).

- Exercise of SARs: Each Share Acquisition Right would entitle the holder to acquire one new common share of Y Corp.

- Exercise Price: The exercise price for each new share upon exercising a Share Acquisition Right was set at a nominal ¥1 per share.

- Discriminatory Exercise Condition (the "Non-Qualified Person" Clause): X, A LLC, and certain other parties related to X (collectively, "X-related parties") were designated as "non-qualified persons." This key provision stipulated that these X-related parties could not exercise their Share Acquisition Rights.

- Discriminatory Acquisition/Redemption by Y Corp (the "Acquisition Clause"): Y Corp's board was authorized to set a date (prior to the SAR exercise period) on which it could acquire all outstanding Share Acquisition Rights. The terms of this acquisition were also discriminatory:

- For all shareholders other than X-related parties, Y Corp would deliver one new common share of Y Corp as consideration for each Share Acquisition Right acquired.

- For X-related parties, Y Corp would pay ¥396 in cash as consideration for each Share Acquisition Right acquired. This cash amount was calculated based on X's initial TO price of ¥1,584 (¥1,584 / 4 = ¥396, effectively reflecting the value of one original share being diluted into four if non-X parties exercised their SARs, and giving X a cash equivalent for their SARs based on their own offer price for the underlying shares).

- Transfer Restriction: Transfer of the Share Acquisition Rights required Y Corp board approval.

The effect of this mechanism, if triggered by Y Corp acquiring the SARs, would be a massive dilution of X-related parties' shareholding in Y Corp (as they would receive only cash for their SARs, while other shareholders would receive new shares, effectively quadrupling their interest relative to X).

The Legal Challenge: Shareholder Equality and Fairness

Prior to the AGM, on June 13, 2007, X filed an application with the Tokyo District Court for a provisional disposition (an interim injunction) to prohibit Y Corp from proceeding with the Share Acquisition Rights Allotment. X argued that the Allotment was illegal, primarily contending that:

- It violated the shareholder equality principle (株主平等の原則 - kabunushi byōdō no gensoku) enshrined in Article 109 of the Companies Act.

- It constituted a "grossly unfair method" of allotting SARs, making it subject to injunction under Article 247 of the Companies Act (which deals with enjoining the issuance of new shares or SARs, applied here by analogy to a gratuitous allotment).

Both the Tokyo District Court and, on appeal, the Tokyo High Court dismissed X's application. They found that the Allotment did not violate the shareholder equality principle and was not a grossly unfair method, primarily because they deemed X to be an "abusive acquirer" and the defensive measure to be necessary and reasonable. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding the Defensive Measure

The Supreme Court, in its decision dated August 7, 2007, dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the legality of Y Corp's poison pill under the specific circumstances. The Court's reasoning was detailed:

1. Shareholder Equality Principle and SAR Allotments

- The Court acknowledged that Article 109, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act obligates a company to treat its shareholders equally according to the content and number of shares they hold.

- While a discriminatory SAR allotment doesn't directly alter the terms of existing shares, the Court reasoned that because shareholders receive SARs by virtue of their status as shareholders, and because the Companies Act (e.g., Article 278, Paragraph 2) generally presumes that SARs allotted to shareholders will have identical terms, the spirit and underlying policy of the shareholder equality principle extend to gratuitous allotments of Share Acquisition Rights.

- The Court recognized that the proposed Allotment, with its discriminatory exercise and redemption conditions, would indeed lead to a significant dilution of X-related parties' shareholding ratio if other shareholders exercised their SARs or had them redeemed for new Y Corp shares.

2. Permissible Differentiation: The Two-Prong Test

Despite the applicability of the shareholder equality principle's spirit, the Court held that differential treatment of a specific shareholder is not an automatic violation. It is permissible if a two-prong test is met:

- Necessity: The differential treatment must be aimed at preventing a situation where a specific shareholder's acquisition of management control would lead to harm to the company's corporate value, thereby damaging the company's interests and, consequently, the common interests of all shareholders. This could occur, for example, if the acquisition would jeopardize the company's continued existence or development.

- Proportionality/Reasonableness (相当性 - sōtōsei): The differential treatment itself must not be contrary to the fundamental principles of equity and must not lack proportionality or reasonableness in light of the threat posed.

3. Assessing "Necessity" – Judicial Deference to Shareholder Judgment

This was a crucial part of the ruling. The Supreme Court stated that the determination of whether a particular shareholder's acquisition of control would indeed harm corporate value and the common interests of shareholders is ultimately a matter to be judged by the shareholders themselves, as they are the beneficial owners of the company.

- Deference to AGM Vote: Consequently, the courts should respect the judgment reached by the shareholders at a general meeting, provided that:

- The shareholder meeting procedures were not themselves improper or unfair.

- The factual premises upon which the shareholders' judgment was based were not non-existent or false, or there were no other serious flaws that would negate the legitimacy of that judgment.

4. Application of "Necessity" to the Facts

- In this case, the defensive measures (the Articles of Incorporation amendment and the SAR Allotment) were approved at Y Corp's AGM by approximately 83.4% of the total voting rights (and about 88.7% of votes present). This, the Court said, indicated that almost all existing shareholders, other than X-related parties, had judged that X's acquisition of control would indeed harm Y Corp's corporate value and their common interests.

- The Court found no evidence of procedural impropriety in the AGM.

- It further noted that the shareholders' judgment appeared to be based on discernible factors, such as X-related parties' stated intention to acquire 100% of Y Corp while simultaneously indicating they had no plans to manage Y Corp directly, and their failure to provide clear post-acquisition management policies or strategies for recovering their invested capital.

- Therefore, the Court concluded that there were no serious flaws in the shareholders' judgment that would warrant overturning it. The "necessity" of the defensive measure, from the perspective of the majority of shareholders, was thus established.

5. Assessing "Proportionality/Reasonableness"

The Court then examined whether the discriminatory Allotment was a proportionate and reasonable response:

- It acknowledged the significant adverse impact on X-related parties: they could not exercise their Share Acquisition Rights to obtain new shares, nor could they receive shares if Y Corp acquired/redeemed the SARs, leading to a substantial dilution of their existing shareholding percentage.

- However, the Court weighed several countervailing factors:

- The Allotment was approved by an overwhelming majority of existing shareholders (excluding X-related parties) after X-related parties had an opportunity to state their views at the AGM. This approval was based on the shareholders' judgment that the measure was necessary to prevent harm to Y Corp's corporate value from X's potential takeover.

- Crucially, X-related parties were not left empty-handed. Under the Acquisition Clause, if Y Corp chose to acquire their Share Acquisition Rights, they would receive a cash payment. Furthermore, even if Y Corp did not formally execute this acquisition for X-related parties (e.g., due to potential adverse tax consequences for other shareholders), Y Corp's board had also passed a resolution offering to purchase the Share Acquisition Rights from X-related parties for the same cash amount (¥396 per SAR) in exchange for X-related parties relinquishing any claims.

- The Court found this cash consideration (¥396 per SAR) to be commensurate with the value of the Share Acquisition Rights, as it was calculated based on X's own initial tender offer price for Y Corp's shares (essentially giving X the per-SAR equivalent of what X itself valued the underlying equity at, divided by four due to the 1:3 SAR allotment).

- Considering these facts, even accounting for the dilutive effect on X-related parties, the Supreme Court concluded that the Share Acquisition Rights Allotment was not contrary to the principles of equity and did not lack proportionality or reasonableness.

- The Court also addressed a potential concern: that Y Corp paying a significant sum to X-related parties for their SARs might itself harm corporate value. It again deferred to the shareholder vote, stating that the vast majority of shareholders evidently judged this cash payment to be an acceptable cost to prevent the greater harm to corporate value perceived from X's acquisition of control, and this judgment should also be respected.

6. Not a "Grossly Unfair Method"

Finally, the Court determined that the Allotment was not undertaken by a "grossly unfair method." This conclusion flowed from its findings on the shareholder equality principle. The Court also noted that the fact Y Corp adopted this defensive measure on an ad hoc basis in direct response to X's tender offer, rather than having a pre-existing, publicly disclosed defense plan, did not, by itself, render the method grossly unfair. It was an emergency measure, approved by shareholders to protect corporate value against a perceived imminent threat, and its purpose was not found to be solely the entrenchment of existing management.

Analysis and Implications

This 2007 Supreme Court decision, often referred to as the "Bull-Dog Sauce case" after the target company's identity, was a landmark in Japanese M&A law:

- Validation of Discriminatory Poison Pills: It provided the first clear Supreme Court endorsement for the use of shareholder-approved, discriminatory Share Acquisition Rights allotments (poison pills) as a legitimate defense against hostile takeovers, provided certain conditions of necessity and proportionality are met.

- The "Necessity and Proportionality" Test: The decision established this two-prong test as the framework for evaluating whether a defensive measure that treats shareholders differently violates the spirit of the shareholder equality principle. This test is a common feature in takeover defense jurisprudence internationally.

- Judicial Deference to Shareholder Votes on "Necessity": A key and somewhat debated aspect of the ruling is the significant deference shown by the Supreme Court to the judgment of a well-informed shareholder majority (excluding the bidder) regarding whether an acquirer poses a threat to corporate value. While emphasizing the need for fair procedures and no fatal flaws in the factual basis of the shareholders' decision, this approach gives considerable power to the collective assessment of existing shareholders. Critics have raised concerns that this might not always protect the interests of all shareholders, especially if a large portion of votes is controlled by "stable shareholders" (such as allied companies in cross-shareholding relationships) who may have interests aligned with management rather than maximizing value for all. The Court, however, implicitly prioritized the AGM as the forum for expressing shareholder will over the potentially coercive environment of a tender offer.

- The "Cash-Out" for the Acquirer's Rights as a Factor in Proportionality: The fact that X-related parties were to receive cash compensation for their Share Acquisition Rights, at a value linked to their own tender offer price, was a significant factor in the Court's finding of proportionality. This suggests that completely disenfranchising a bidder without any compensation for the defensive rights they are also allotted might be viewed less favorably. However, some commentators have questioned whether this "pay-off" to the hostile acquirer for their SARs could, in some circumstances, resemble "greenmail" if the payment is not carefully calibrated or if the acquirer was not, in fact, a genuine threat to long-term corporate value. The Court, in this instance, appeared to accept the shareholder majority's judgment that this cost was acceptable.

- Ad Hoc Defenses Not Inherently Unfair: The ruling indicates that a takeover defense adopted on an ad hoc basis in response to a specific, unwelcome bid is not automatically deemed grossly unfair, provided it is approved by shareholders for legitimate defensive purposes (i.e., protecting corporate value) rather than solely for management entrenchment. Nevertheless, pre-disclosed, pre-approved defense policies generally offer greater transparency and predictability for the market.

Conclusion

The August 7, 2007, Supreme Court decision in this prominent takeover defense case established important principles regarding the use of discriminatory poison pills in Japan. It affirmed that such measures, while implicating the spirit of shareholder equality, can be legally permissible if they are deemed necessary by a well-informed and procedurally sound shareholder majority to protect corporate value from a perceived threat, and if the measures themselves are proportionate and not fundamentally inequitable—a standard that, in this case, was met partly by providing the hostile bidder with fair cash compensation for the defensive rights they were prevented from exercising. The case underscores the delicate balance courts must strike between facilitating legitimate corporate defense, respecting shareholder democracy, and upholding the underlying principles of fairness and equality among shareholders.