Point of No Return? Japan's Supreme Court on Resignation Acceptance and Retraction (September 18, 1987)

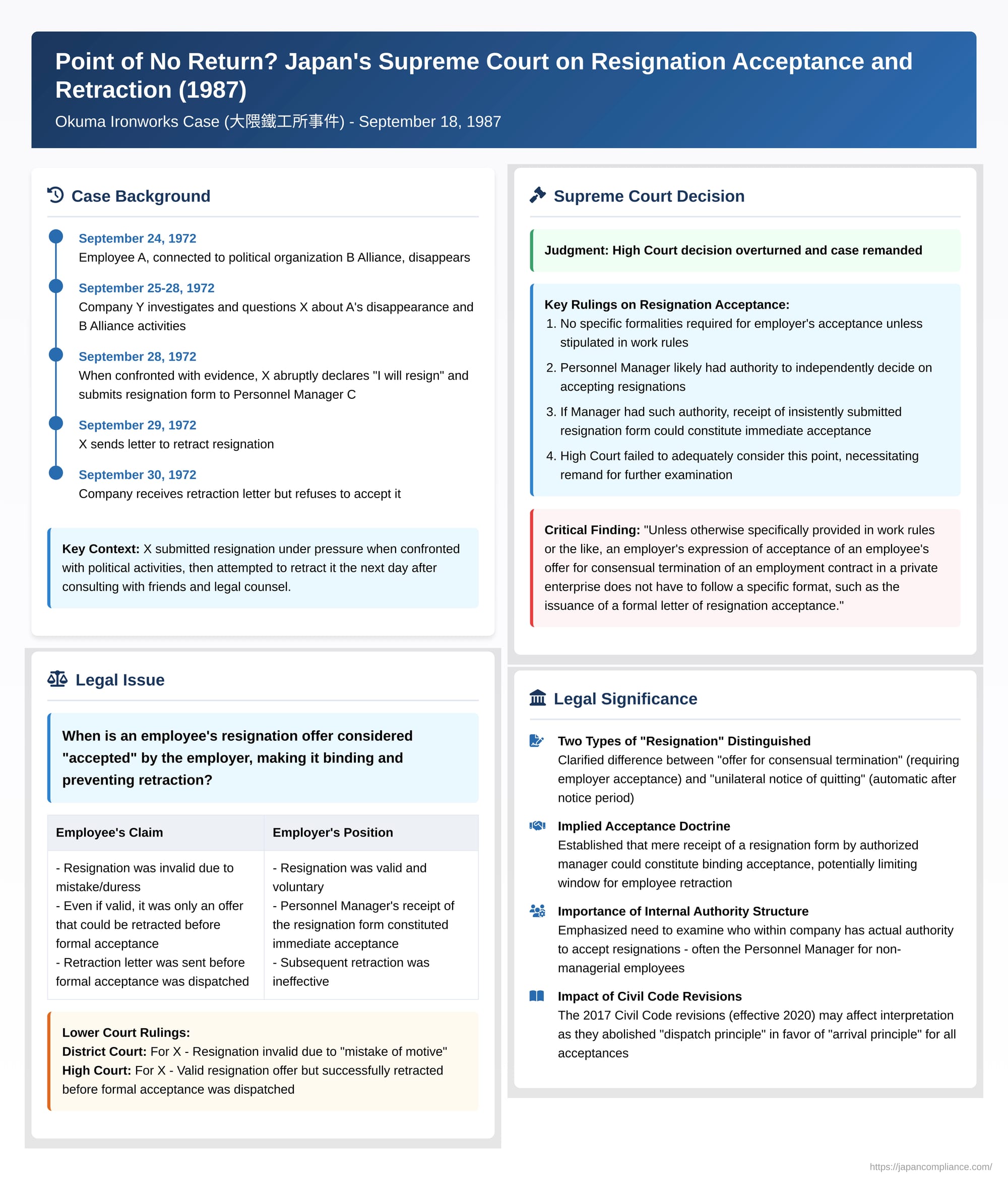

On September 18, 1987, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a case commonly known as the "Okuma Ironworks Case" (大隈鐵工所事件). This ruling addressed the critical question of when an employee's offer to resign from their employment becomes a binding agreement, thereby precluding subsequent retraction. Specifically, it examined what constitutes an employer's acceptance of such a resignation and whether formal procedures are always necessary for that acceptance to be effective.

An Abrupt Resignation Under Pressure

The plaintiff, X, a university graduate, had been employed by Defendant Company Y, an ironworks company, since the spring of 1972. X was covertly involved in activities related to an external political organization, the B Alliance, including attempting to recruit colleagues. Another employee, Colleague A, who was also involved in these activities with X, found himself in emotional turmoil over his affiliation with the B Alliance and his desire to leave it. On the evening of September 24, 1972, Colleague A disappeared.

Company Y launched an investigation into Colleague A's disappearance. Upon searching Colleague A's room in the company dormitory, management discovered materials related to the B Alliance, which implicated both Colleague A and Plaintiff X. The company also learned that X had been in contact with Colleague A shortly before the disappearance. Starting September 25, Company Y's personnel department repeatedly questioned X regarding Colleague A's whereabouts and reasons for disappearing. X consistently denied having any knowledge of the matter.

The situation came to a head on the afternoon of September 28, 1972. With no progress in locating Colleague A, C, Company Y's Personnel Department Manager, met with X in a company reception room, accompanied by two subordinates. During this meeting, Manager C presented X with the B Alliance-related documents that had been found in Colleague A's room.

According to the facts established by the lower court, X reacted with stunned silence for a moment, then abruptly declared, "I will resign. I have absolutely no connection to Mr. A's disappearance.". Despite Manager C's attempts to dissuade X, stating that affiliation with the B Alliance was not, in itself, a reason for resignation, X remained insistent. X then filled out a standard resignation form provided by Manager C, citing "personal reasons" as the cause for resignation, signed it, and submitted it to Manager C, who received it. X subsequently completed some initial departure procedures and left the company premises that evening.

The Attempted Retraction

After leaving the company, X consulted with friends and legal counsel. The very next day, September 29, X dispatched a registered letter to Company Y, which was received on September 30, formally stating an intention to retract the resignation submitted on September 28. Company Y refused to accept this retraction, maintaining that a valid resignation had already been accepted.

X then filed a lawsuit, arguing that the expression of intent to resign was invalid due to factors such as mistake of motive or duress, and sought confirmation of continued employment status with Company Y.

The Lower Courts: Differing Paths to a Similar Outcome for X

- Nagoya District Court (First Instance): The District Court ruled in favor of X, finding the resignation to be invalid. Its reasoning was based on the doctrine of "mistake of motive" (動機の錯誤 - dōki no sakugo) under Article 95 of the Civil Code, implying that X's decision to resign was based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the situation or its consequences.

- Nagoya High Court (Appeal): The High Court also found in favor of X, thereby upholding X's employment status, but on different legal grounds. It interpreted X's submission of the resignation form not as a void expression of intent, but as a valid offer to mutually terminate the employment contract (雇用契約を合意解約する申込みの意思表示 - koyō keiyaku o gōi kaiyaku suru mōshikomi no ishi hyōji). The High Court then reasoned that X had successfully retracted this offer before Company Y had formally dispatched its acceptance of the offer. This finding allowed X to withdraw the resignation.

Company Y appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Key Rulings and Remand

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Supreme Court found the High Court's reasoning regarding when an employer's acceptance of a resignation offer becomes effective to be flawed.

I. No Specific Formalities Required for Employer's Acceptance

The Supreme Court clarified a general principle regarding the acceptance of resignations: "Unless otherwise specifically provided in work rules or the like, an employer's expression of acceptance of an employee's offer for consensual termination of an employment contract in a private enterprise does not have to follow a specific format, such as the issuance of a formal letter of resignation acceptance (辞令書の交付 - jireisho no kōfu)". This means that formal documentation is not inherently necessary for an employer's acceptance to be legally valid.

II. Authority of the Personnel Manager and the Nature of Acceptance

The Court then focused on the role and authority of Personnel Manager C:

- It stated that it is "not unreasonable according to common experience" for a company to grant its Personnel Department Manager—who is typically in a position to assess employee capabilities, character, performance, and other relevant factors—the authority to "independently decide" on matters such as accepting employee resignations.

- The Supreme Court noted that evidence presented (including the format of Company Y's resignation forms and potentially its internal regulations) suggested that the Personnel Manager's approval might indeed be the final step in the resignation process for employees below a certain managerial rank.

- The Crucial Interpretive Point: "If [Personnel Manager] C had the authority to decide on the acceptance of X's resignation letter, then, under the factual circumstances described... it is rather natural to interpret that Company Y's immediate acceptance of the offer to terminate the employment contract was expressed when Manager C received X's resignation letter". The SC suggested that in such a situation, the act of the duly authorized manager receiving the resignation form, especially given X's insistence on resigning despite attempts at dissuasion, could itself constitute the company's acceptance, thereby forming a binding agreement for termination at that moment.

Conclusion and Remand for Further Deliberation

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded that the High Court's finding—that acceptance had not yet occurred when X attempted to retract—was potentially flawed because it did not adequately consider whether Manager C's receipt of the resignation, given C's potential authority, amounted to immediate acceptance. "For the reasons above, the original judgment... cannot escape being overturned," the Court stated. The case was remanded to the Nagoya High Court "for further deliberation on this point" —specifically, to determine more conclusively Manager C's actual authority to independently approve resignations and whether, under all circumstances, C's receipt of X's resignation form constituted an immediate and binding acceptance on behalf of Company Y.

Deeper Dive: The Legal Nuances of Resignation in Japan

This Supreme Court judgment touches upon several complex aspects of Japanese employment law regarding the termination of employment by employee initiative.

- Two Types of "Resignation":

- Offer for Consensual Termination (合意解約の申込み - gōi kaiyaku no mōshikomi): This is when an employee offers to end the employment contract by mutual agreement with the employer. It requires a clear acceptance from the employer to become legally effective. The Okuma Ironworks case was treated by the courts as falling into this category.

- Unilateral Resignation/Notice of Quitting (辞職の意思表示 - jishoku no ishi hyōji): Under Article 627, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code, an employee under an indefinite-term employment contract has the right to unilaterally resign by giving a specified period of notice (typically two weeks). This type of resignation does not require the employer's acceptance to take effect; the employment relationship terminates automatically after the notice period expires.

The commentary notes that in practice, it can often be difficult to distinguish whether an employee's "statement of resignation" constitutes an offer for consensual termination or a unilateral notice of quitting. Lower courts in Japan tend to interpret most employee-initiated resignations as offers for consensual termination.

- Challenging a Resignation: Defects vs. Retraction:

- Defects in Formation (欠缺・瑕疵 - kenketsu・kashi): An employee's expression of intent to resign can be challenged if its formation was flawed due to legal concepts such as mental reservation (Civil Code Art. 93), mistake (Art. 95), or fraud/duress (Art. 96). If such a defect is proven, the resignation may be deemed void or be voidable, potentially allowing the employee to maintain their employment status. The first instance court in the Okuma case had initially invalidated X's resignation based on mistake.

- Retraction (撤回 - tekkai): More commonly, disputes arise over an employee's attempt to retract their offer for consensual termination. The general rule, accepted by the Supreme Court in this case (based on prior lower court trends), was that an employee could retract their offer for consensual termination at any time before the employer dispatched its acceptance. This made the precise moment of the employer's acceptance critically important.

- Determining Employer's Acceptance:

- The Okuma Supreme Court judgment emphasized that the determination of who within a company has the authority to accept a resignation (the "final decision-maker") and when that acceptance is legally perfected often requires a close examination of the company's internal rules, procedures, and the customary handling of such matters (e.g., the routing of resignation forms, internal regulations on approval powers). This factual inquiry was central to the reason for remand.

- The Supreme Court's suggestion that acceptance could be implied by an authorized manager simply receiving an insisted-upon resignation, without further formal steps, was a significant point, potentially narrowing the window for employee retraction.

- Academic Criticism and the Impact of Civil Code Revisions (2017):

- Many legal scholars, as noted in the commentary, have criticized the Supreme Court's reasoning in Okuma, particularly the idea that mere receipt of a resignation by an authorized manager could immediately constitute binding acceptance. Such an interpretation makes it very difficult for employees to retract a resignation, even if made hastily or under pressure.

- The commentary highlights an important subsequent legal development: the 2017 revision of the Japanese Civil Code (which came into effect on April 1, 2020). This revision abolished the "dispatch principle" (発信主義 - hasshin shugi) for the acceptance of offers between distant parties (former Civil Code Art. 526(1)) and uniformly adopted the "arrival principle" (到達主義 - tōtatsu shugi) for all expressions of intent, including acceptance (new Civil Code Art. 97(1)). The Okuma judgment's reasoning on implied acceptance might have been influenced by the old dispatch principle. It remains to be seen how courts will interpret the timing and effect of an employer's acceptance of a resignation under the revised Civil Code, which now consistently requires the acceptance to reach the offeror (the employee) to be effective.

- The Broader Context of "Involuntary Resignations": The commentary also touches upon a wider concern in Japanese labor law: ensuring that an employee's decision to resign is genuinely voluntary and based on their free will, especially in situations where there might be employer pressure or difficult circumstances (these are sometimes termed "involuntary resignations" - 不本意退職, fuhon'i taishoku). Courts are increasingly expected to scrutinize the objective reasonableness of an employer's belief that an employee freely consented to terminate their employment.

Conclusion: Defining the Moment of Binding Resignation

The Supreme Court's 1987 decision in the Ironworks Company Y (Okuma Ironworks) case provided important, albeit debated, clarifications on the mechanics of resignation in Japan. It established that an employer's acceptance of an employee's offer to resign (construed as an offer for consensual termination) does not necessarily require specific formal procedures like a written letter of acceptance, unless stipulated by company rules. More controversially, it suggested that the act of an authorized manager receiving an insisted-upon resignation could, under certain circumstances, constitute immediate and binding acceptance by the company, thereby precluding the employee from subsequently retracting it.

The case underscored the critical importance of identifying who within a company holds the authority to accept resignations and precisely when their acceptance becomes legally effective. While the judgment aimed to provide clarity, its implications for an employee's ability to retract a hastily made resignation offer have been a subject of ongoing academic discussion, particularly in light of subsequent revisions to the Civil Code that emphasize the "arrival principle" for acceptances. The Okuma case remains a key reference point in disputes over the finality of an employee's decision to resign.