Pledgor's Dilemma: Duty to Preserve Value of Pledged Security Deposit Claim - A Japanese Supreme Court Analysis

Date of Judgment: December 21, 2006

Case Name: Claim for Damages

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

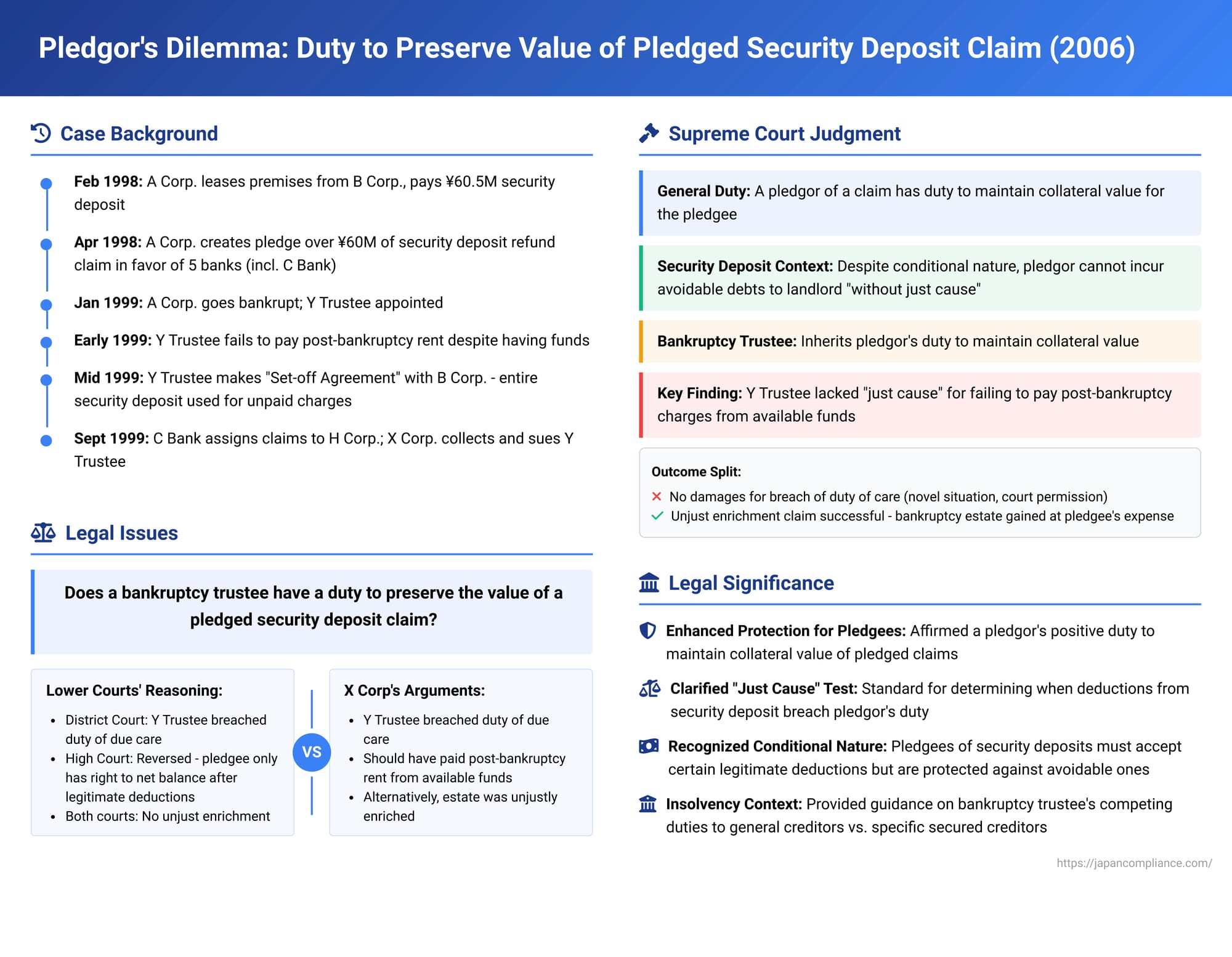

In finance and commerce, a "pledge of a claim" (saiken shichi) is a common form of security where a debtor (pledgor) grants a security interest over a claim they hold against a third party, in favor of their creditor (pledgee). A frequently pledged asset in Japan, particularly in real estate leases, is the lessee's "security deposit refund claim" (shikikin henkan seikyūken) against the lessor. This claim, however, is conditional by nature. A pivotal Supreme Court of Japan judgment on December 21, 2006, delved into the obligations of a pledgor (the lessee) towards the pledgee concerning the preservation of the value of such a uniquely conditional pledged claim, especially in the complex context of the pledgor's bankruptcy.

The Intricate Factual Background: A Lease, A Pledge, A Bankruptcy

The case arose from a series of commercial arrangements involving A Corp., its landlord B Corp., and its lenders.

- The Lease and Security Deposit: On February 13, 1998, A Corp. leased four distinct sections of a building (an office, a residential unit, a parking area, and a warehouse – collectively, "the Leased Premises") from B Corp., a real estate company. Upon entering into these leases and taking possession, A Corp. paid B Corp. a substantial total security deposit (shikikin) amounting to over ¥60.5 million.

- The Pledge: On April 30, 1998, A Corp. created a pledge (shichiken) over ¥60 million of its security deposit refund claim against B Corp.. This pledge was established in favor of a consortium of five financial institutions, including C Bank, to secure all existing and future debts A Corp. owed to them. B Corp. (the lessor and debtor of the security deposit refund claim) acknowledged and consented to this pledge by way of a notarized document bearing a certified date (kakutei hizuke), a formality that helps establish the timing of the consent against third parties. The agreement among the pledgee banks stipulated that if the pledge were enforced, C Bank would be entitled to receive 87/262 of any proceeds.

- Bankruptcy and the Trustee's Actions: On January 25, 1999, A Corp. was declared bankrupt, and Y Trustee was appointed to manage the bankrupt estate. Despite the bankruptcy estate reportedly having sufficient cash reserves in bank accounts, Y Trustee failed to pay certain post-bankruptcy rents and common service fees due to B Corp. for the Leased Premises. Subsequently, Y Trustee, having obtained permission from the bankruptcy court for most parts, entered into an agreement (the "Set-off Agreement") with B Corp.. Under this agreement, the lease agreements for the Leased Premises were mutually terminated, A Corp. (via Y Trustee) vacated the premises, and the entire security deposit was applied to cover B Corp.'s claims against A Corp., which included unpaid rent, unpaid common service fees, and costs for restoring the premises to their original condition.

- Assignment and Lawsuit: On September 20, 1999, C Bank assigned its claims against the bankrupt A Corp., along with all associated security rights including its share of the pledge over the security deposit, to H Corp., a Dutch entity. H Corp. then engaged X Corp., a licensed Japanese debt collection agency, to collect on these claims. X Corp., acting on behalf of H Corp., initiated a lawsuit against Y Trustee. X Corp. argued that Y Trustee's Set-off Agreement, particularly the use of the security deposit to cover post-bankruptcy charges when other funds were available, constituted a breach of the trustee's duty of due care as a good manager (zenkan chūi gimu) owed to creditors, including the pledgees. This breach, X Corp. contended, effectively rendered the pledge over the security deposit worthless and improperly undermined the pledgee's priority right to be satisfied from those funds. X Corp. sought, alternatively, damages for this breach of duty or restitution for unjust enrichment of the bankruptcy estate.

The Legal Path to the Supreme Court

The lower courts had differing views on Y Trustee's liability:

- The District Court: Found that Y Trustee had indeed breached the duty of due care by not paying the post-bankruptcy rent and common service fees from available estate funds and instead offsetting them against the security deposit, which was subject to the pledge. It thus awarded damages to X Corp.. However, it denied X Corp.'s alternative claim for unjust enrichment, reasoning that while the bankruptcy estate avoided paying certain expenses, it also "lost" the security deposit refund claim asset, resulting in no net gain to the estate.

- The High Court: Overturned the District Court on the damages claim. It held that a pledgee of a security deposit refund claim inherently only has a priority right over any net balance of the deposit remaining after the landlord has deducted all legitimate claims. Therefore, Y Trustee's actions in allowing such deductions were not a breach of the duty of due care. The High Court agreed with the District Court in denying the unjust enrichment claim, based on similar reasoning that the estate experienced no net benefit.

X Corp. then sought and was granted leave to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment (December 21, 2006): Key Principles

The Supreme Court partially reversed the High Court's decision, notably finding in favor of X Corp. on the unjust enrichment claim. The judgment laid down several important principles:

- Pledgor's General Duty to Maintain Collateral Value of a Pledged Claim: The Court affirmed a fundamental principle: when a claim (an intangible asset) is pledged as security, the pledgor (the one who grants the pledge) owes a duty to the pledgee (the one who receives the pledge) to maintain the collateral value of that pledged claim. Consequently, any actions by the pledgor such as waiving, releasing, setting off, or novating the pledged claim, or any other conduct that extinguishes, alters, or otherwise impairs its value as collateral, are considered a violation of this duty and are not permissible.

- Application to Pledged Security Deposit Refund Claims: The Court then specifically applied this duty to the context of a pledged security deposit refund claim. It acknowledged the nature of such a claim: it is a conditional right that materializes only upon the termination of the lease and the vacation of the leased premises, and only for the amount of the security deposit that remains after the landlord has deducted all outstanding claims arising from the lease (such as unpaid rent, damages for breach, restoration costs, etc.). This characterization of a security deposit refund claim as conditional was based on an earlier Supreme Court precedent (Supreme Court, February 2, 1973).

Despite this conditional nature, the Court ruled that if a lessee (who is the pledgor of their security deposit refund claim) without just cause incurs unpaid debts to the landlord (e.g., by failing to pay rent), thereby preventing the security deposit refund claim from arising or reducing its potential amount, such conduct constitutes a breach of the duty owed to the pledgee to maintain the collateral value of the pledged claim. - Bankruptcy Trustee Inherits the Pledgor's Duty: The Supreme Court stated that when a pledgor (like A Corp.) enters bankruptcy, their bankruptcy trustee (Y Trustee) succeeds to the duties the pledgor owed to the pledgee, including this duty to maintain collateral value. A pledge is recognized as a "right of separation" (betsujoken) in Japanese bankruptcy law, meaning it allows the secured creditor to seek satisfaction from the collateral outside the normal bankruptcy distribution process, and its validity is generally not affected by the bankruptcy proceedings themselves.

- Y Trustee's Actions and "Just Cause":

- Restoration Costs: The Court found that applying the security deposit to cover the costs of restoring the Leased Premises to their original condition was generally permissible and supported by "just cause." This is because such deductions are a common and widely accepted practice in leases, and a pledgee of a security deposit refund claim would typically anticipate such deductions when assessing the collateral's value.

- Post-Bankruptcy Charges (Rent and Common Service Fees): However, regarding the application of the security deposit to cover post-bankruptcy rent and common service fees, the Court found Y Trustee's actions to lack "just cause". The facts established that the bankruptcy estate possessed sufficient liquid funds (bank deposits) to pay these charges as they fell due. Choosing not to pay them from these available funds and instead using the pledged security deposit, even if intended to preserve assets for general bankruptcy creditors, was not justifiable. Post-bankruptcy administrative expenses, such as rent for premises occupied by the trustee, are considered "estate claims" (zaidan saiken), which have priority over general bankruptcy claims and should be paid from the estate as they arise. Therefore, Y Trustee's failure to pay these charges and instead allowing them to deplete the security deposit was a breach of the inherited duty to maintain collateral value owed to the pledgees.

- Trustee's Liability – Damages vs. Unjust Enrichment:

- Damages for Breach of Duty of Due Care: Despite finding that Y Trustee had violated the duty to maintain the collateral value (which is a specific duty owed to the pledgee), the Supreme Court did not hold Y Trustee liable for damages under the general framework of a bankruptcy trustee's breach of their duty of due care as a good manager. The Court reasoned that the issue involved a complex balancing of a trustee's duty to the general body of creditors (to preserve the estate) and the specific duties inherited from the bankrupt pledgor towards a secured creditor (the pledgee). Given the scarcity of established legal precedent and academic opinion on this precise conflict at the time, and the fact that Y Trustee had obtained bankruptcy court permission for the Set-off Agreement (for most of the leased portions), the Court concluded that Y Trustee's conduct, while ultimately found to be a breach of the specific value-maintenance duty, did not sink to the level of breaching the general standard of care expected of an "average" bankruptcy trustee in such a novel and difficult situation.

- Restitution of Unjust Enrichment: However, the Supreme Court found that X Corp.'s claim for unjust enrichment was valid. The Court noted that the pledged security deposit refund claim was, in this case, almost entirely "captured" by the pledge, as the amount pledged was nearly the full deposit and the secured debts far exceeded this amount. When the bankruptcy estate (managed by Y Trustee) avoided paying the Post-Bankruptcy Charges out of its ample free cash and instead used the security deposit via the Set-off Agreement, the estate effectively gained by the amount of expenses it didn't pay. This gain came directly at the expense of the pledgees, who lost their ability to receive priority satisfaction from that portion of the security deposit. The High Court's reasoning that the estate suffered an equivalent loss (the extinguishment of the security deposit refund claim as an asset) was deemed flawed because that particular asset was already fully encumbered by the pledge and thus not truly available for the general creditors. The bankruptcy estate was therefore unjustly enriched by the pledgees' loss. X Corp. was awarded its pro-rata share (87/262) of the amount of Post-Bankruptcy Charges (excluding restoration costs and a small sum applied before the pledge was assigned to H Corp.) that had been improperly offset against the security deposit.

Deep Dive: The Pledgor's Duty to Maintain Collateral Value of a Claim

This Supreme Court judgment robustly establishes that a pledgor of a claim has a positive duty to the pledgee to maintain the collateral value of that pledged claim. While the Japanese Civil Code does not explicitly detail such a comprehensive duty for pledgors of claims (unlike some provisions for pledges of tangible assets), it is derived from the fundamental nature of the pledge as a security right. The pledgee is understood to have an exclusive right to the economic value of the pledged claim. Consequently, the pledgor is not permitted to undertake actions that would undermine this security. Prohibited acts include:

- Waiving or releasing the pledged claim.

- Entering into a set-off concerning the pledged claim with the debtor of that claim.

- Novating the pledged claim (replacing it with a new one).

- Any other conduct that extinguishes, alters, or otherwise impairs the pledged claim's value as collateral for the pledgee.

This principle finds support in earlier, though less direct, case law. For instance, an old Great Court of Cassation decision (March 18, 1926) held a pledgor's attempt to set off the pledged claim to be invalid against the pledgee, reasoning that the pledgor no longer possessed the right to collect the claim. Another Supreme Court decision (April 16, 1999) ruled that a pledgor could not file for the bankruptcy of the third-party debtor of the pledged claim if doing so would significantly prejudice the pledgee's ability to realize their security.

The Unique Nature of a Pledged Security Deposit Refund Claim

A security deposit refund claim is a peculiar asset to pledge because its existence and amount are conditional. It only comes into being as a definite monetary claim for any remaining balance of the deposit after the lease ends, the tenant vacates, and the landlord deducts all amounts legitimately owed by the tenant under the lease (e.g., unpaid rent, damages, restoration costs). This inherent contingency means its value as collateral is not fixed.

The High Court in this case had partly reasoned that a pledgee accepts this inherent uncertainty. However, the Supreme Court clarified that while the conditional nature is recognized, it does not give the pledgor (lessee) carte blanche to actively and unjustifiably diminish the potential refund by incurring avoidable debts to the landlord.

Defining "Just Cause" for Diminishing the Security Deposit

The Supreme Court's criterion for whether a lessee-pledgor breaches their duty to the pledgee is whether they incurred debts to the landlord (which then deplete the security deposit) "without just cause". The judgment provided guidance on what might constitute "just cause" in the context of the bankruptcy trustee's actions, which can be extrapolated to the pledgor themselves:

- Deducting Restoration Costs: Applying the security deposit to cover reasonable costs for restoring the leased premises to their original condition is generally considered to have "just cause." Such deductions are a standard feature of commercial leases, and a pledgee would typically anticipate this when evaluating the security deposit as collateral.

- Deducting Unpaid Rent/Fees Despite Solvency: Conversely, if the lessee (or, as in this case, the bankruptcy estate) has sufficient funds to pay rent and other lease-related charges but deliberately fails to do so, allowing these unpaid amounts to be offset against the security deposit, this would generally lack "just cause". This is especially true if the non-payment appears to be a strategic choice to, for example, preserve unencumbered cash at the expense of the pledgee's security.

This implies that while a pledgee of a security deposit refund claim must accept the risk of legitimate deductions by the landlord, they are protected against the pledgor unjustifiably manufacturing or inflating such deductions through avoidable defaults.

Consequences of a Pledgor Breaching the Duty

The judgment primarily dealt with the consequences for a bankruptcy trustee and focused on unjust enrichment rather than damages for breach of a general duty of care in that specific context. For a pledgor directly breaching this duty to maintain collateral value, legal commentators suggest potential consequences:

- The pledgor's actions that diminish the collateral's value (e.g., an improper set-off or waiver) might be deemed ineffective against the pledgee, perhaps by analogy to Civil Code Article 481(1) (which restricts a debtor from acts impairing an assignee's rights after consenting to a pledge on the claim they owe) or Civil Execution Act Article 145(1) (regarding effects of attachment).

- If the pledgor acted with intent or negligence in breaching this duty, they might also face tort liability for damages caused to the pledgee.

A complex issue arises if the consequence of the pledgor's breach is that the landlord's ability to set off claims against the deposit becomes subordinate to the pledgee's rights, especially if the pledgor is insolvent. Given that the security deposit primarily serves as security for the landlord (a point affirmed in other Supreme Court cases, e.g., Supreme Court, March 28, 2002), a careful balancing act is required when determining the effects of a pledgor's breach of duty to the pledgee.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of December 21, 2006, provides a vital clarification regarding the duties of a pledgor, particularly when the pledged asset is a conditional security deposit refund claim. It establishes that pledgors must act to preserve the value of this collateral for their pledgees and cannot, without just cause, take actions (such as incurring avoidable rent defaults) that would diminish or extinguish the pledged claim. While the Court was cautious in finding a breach of a bankruptcy trustee's general duty of due care under the specific complex circumstances and limited precedents, it clearly recognized the underlying breach of the specific duty to maintain collateral value and provided a remedy through the doctrine of unjust enrichment. This decision reinforces the integrity of pledges over claims and offers important guidance for lessees, lessors, and financial institutions involved in such security arrangements.