Gig-Economy Workers in Japan: What the Nov 2022 Tokyo Ruling Means for Platforms

TL;DR

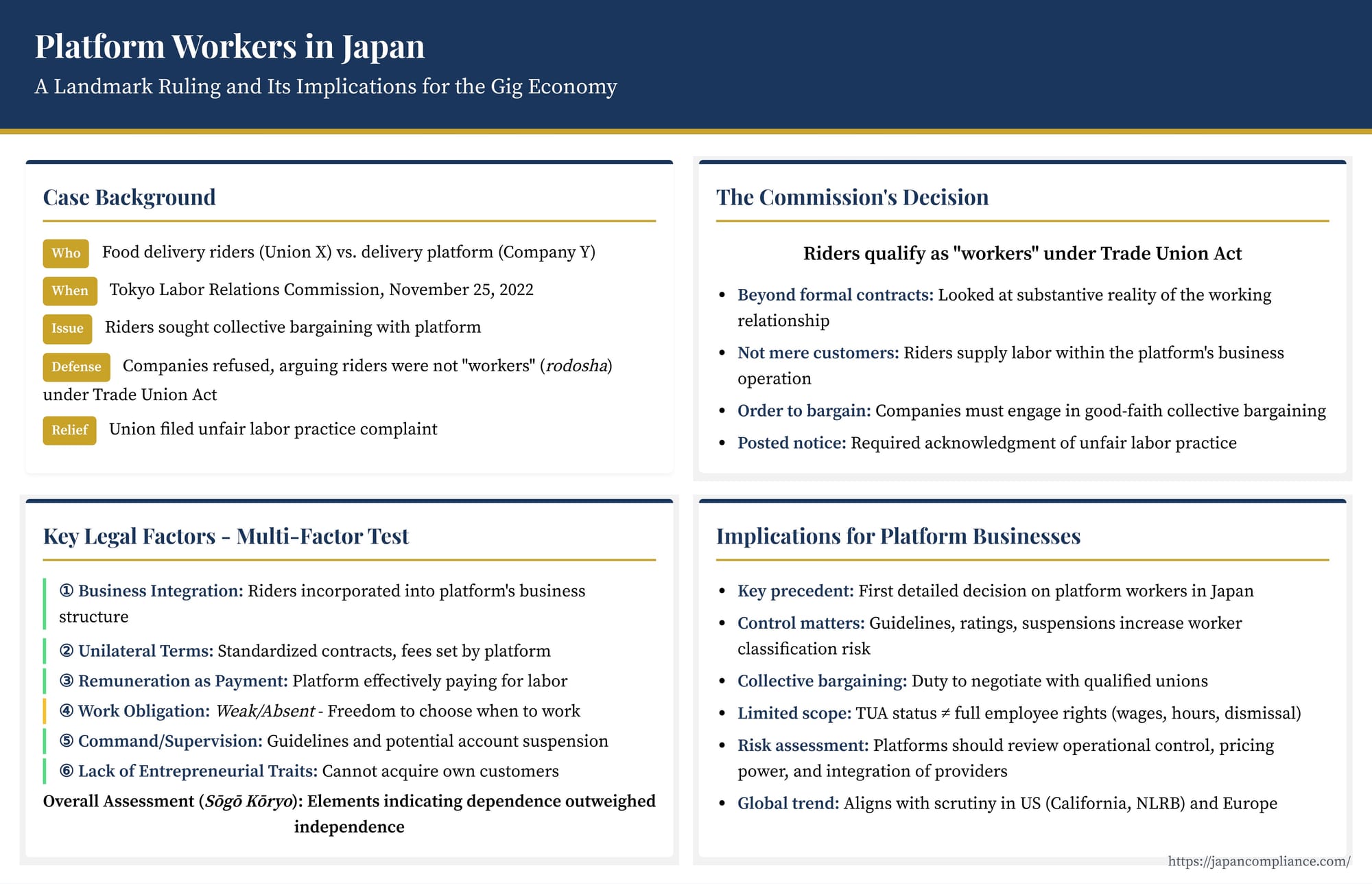

A November 25 2022 Tokyo Labor Relations Commission decision held that food-delivery riders are “workers” under Japan’s Trade Union Act, despite flexible hours, because the platform sets pay, enforces rules, and integrates riders into its core service. Platforms that exert similar control now face collective-bargaining duties, though full employee status under other labor laws remains a separate test.

Table of Contents

- The Tokyo Labor Relations Commission Case (November 25 2022)

- Legal Framework: Who is a "Worker" under Japan's Trade Union Act?

- The Commission's Reasoning: Applying the Multi-Factor Test

- Significance and Implications for Platform Businesses

- Conclusion

The rise of the gig economy, facilitated by digital platforms, has presented legal systems worldwide with a fundamental challenge: how to classify the individuals providing services through these platforms. Are they independent entrepreneurs, traditional employees, or something in between? This classification carries significant consequences for labor rights, social security contributions, and the platform companies' obligations. Japan is actively confronting this issue, and a notable decision by the Tokyo Labor Relations Commission on November 25, 2022, involving food delivery riders, offers crucial insights into how Japanese labor law might apply to the platform-based workforce.

The Tokyo Labor Relations Commission Case (November 25, 2022)

Background

The case involved a labor union ("Union X") formed by delivery partners ("riders") engaged by an international food delivery platform company ("Company Y"). Company Y utilized an app to connect three parties: restaurants, customers ordering food, and the riders delivering the food. A Japanese subsidiary ("Company Z") managed rider registration, onboarding, support, and other related operations under contract with Company Y.

In October and November 2019, Union X sought to engage in collective bargaining with Company Z and Company Y, respectively, concerning issues such as compensation for accidents occurring during deliveries and reductions in delivery fees. Both companies refused to bargain, primarily arguing that the delivery riders were not "workers" (労働者 - rodosha) as defined under Japan's Trade Union Act (労働組合法 - Rodo Kumiai Ho, hereinafter "TUA") and therefore lacked the right to collective bargaining. Consequently, Union X filed an unfair labor practice complaint with the Tokyo Labor Relations Commission (東京都労働委員会 - Tokyo-to Rodo Iinkai), seeking an order compelling the companies to bargain.

The Commission's Decision

The Commission ruled entirely in favor of Union X . It determined that the delivery riders did qualify as "workers" under the TUA and ordered Company Y and Company Z to engage in collective bargaining with the union in good faith. The Commission also mandated the posting of a notice acknowledging the refusal to bargain was an unfair labor practice (a standard remedy known as a "post-notice").

Legal Framework: Who is a "Worker" under Japan's Trade Union Act?

It is essential to understand the specific legal context. The TUA grants individuals defined as "workers" the rights to organize, bargain collectively, and engage in collective action. This definition is distinct from and generally considered broader than the definition of "employee" (also often translated as "worker") under other core labor statutes like the Labor Standards Act (労働基準法 - Rodo Kijun Ho), which governs minimum wages, working hours, paid leave, and dismissal protections.

Whether an individual qualifies as a TUA "worker" is determined not merely by the formal contractual arrangement but by the substantive reality of the working relationship . Japanese labor commissions and courts have developed a multi-factor test to assess this reality, focusing on the degree of economic dependence of the individual on the hiring entity and their level of integration into the entity's business operations. While TUA status grants collective bargaining rights, it does not automatically confer all the protections afforded to employees under the Labor Standards Act.

The Commission's Reasoning: Applying the Multi-Factor Test

The Tokyo Labor Relations Commission meticulously applied the established multi-factor test to the relationship between the delivery platform and its riders.

1. Looking Beyond Contractual Form: The Commission acknowledged that the contracts framed the platform as merely providing a connection service for independent users (restaurants, customers, riders), implying no direct employment or service provision relationship between the platform and the riders . However, citing the purpose and nature of the TUA, the Commission emphasized the need to look beyond such formalities and assess the objective reality of the situation .

2. Riders as More Than "Mere Customers": The platform argued riders were simply "customers" using its app. The Commission rejected this, finding it difficult to view riders solely as customers . It pointed out that the platform actively engaged in various ways to ensure the smooth and stable execution of delivery services – a function deemed indispensable to the platform's overall business of getting restaurant food to consumers. This engagement included:

* Setting guidelines for rider conduct (e.g., prohibiting detours).

* Threatening or implementing account suspension for guideline violations.

* Operating support centers to handle issues arising during deliveries.

This level of involvement strongly suggested, in the Commission's view, that riders were supplying labor within the platform's broader business operation .

3. Analysis of Specific Factors: The Commission then assessed the relationship against the key factors typically used to determine TUA worker status :

- ① Integration into the Business Organization (事業組織への組入れ): Factor Present. The Commission found the riders were incorporated into the platform's business structure. The platform relied on securing a large number of riders for its business model and revenue. It controlled rider behavior through performance evaluations (based on customer/restaurant feedback), adherence to guidelines, and the potential for account suspension. It also used financial incentives to effectively encourage a certain level of exclusive engagement from riders. These elements indicated riders were not operating wholly independently but were managed components of the platform's service delivery system.

- ② Unilateral/Standardized Contract Terms (契約内容の一方的・定型的決定): Factor Present. Riders had no ability to negotiate the terms of their service agreements; the platform used standardized contracts. Critically, delivery fees were determined by the platform, and riders had no practical means to negotiate these fees individually. The platform retained the discretion to change the fee structure and had done so without prior consultation with riders.

- ③ Remuneration as Payment for Labor (報酬の労務対価性): Factor Present. Although contracts might have stipulated that restaurants paid the delivery fees, the Commission looked at the reality. The platform determined the fee amounts. Even during promotions where the platform offered "free delivery" to customers, the platform itself paid the riders their fees. Combined with the platform's operational involvement (guidelines, suspensions etc.), the Commission concluded that, in substance, the platform was paying the riders for the labor they provided within its business operation.

- ④ Obligation to Accept Work Requests (業務の依頼に応ずべき関係): Factor Weak/Absent. The Commission found this factor did not strongly indicate worker status. Riders retained significant freedom regarding whether and when to work (by choosing whether to be online) and substantial freedom to accept or reject specific delivery requests offered through the app.

- ⑤ Work Under Command/Supervision; Time/Place Constraints (指揮監督下の労務提供、時間的場所的拘束): Factor Present (in a broad sense). While riders were not subject to direct constraints on their working hours or specific locations imposed by the platform, the Commission found they operated under a broad form of command and supervision. This was exercised through the platform's operational guidelines and the enforcement mechanism of account suspension, which effectively compelled compliance with the platform's prescribed work procedures.

- ⑥ Notable Entrepreneurial Characteristics (顕著な事業者性): Factor Absent. The Commission determined that the riders lacked significant characteristics of independent entrepreneurs. They could not independently acquire their own customers, nor could they typically hire others to perform deliveries on their behalf (use substitutes). Their income depended directly on performing deliveries requested via the platform according to its system.

4. Overall Assessment (総合考慮 - Sogo Koryo): Weighing all these factors together, the Commission concluded that the elements indicating dependence and integration (①, ②, ③, ⑤) substantially outweighed the elements suggesting independence (primarily ④), and that the riders lacked key entrepreneurial characteristics (⑥). Therefore, in their relationship with the platform companies, the delivery riders qualified as "workers" under the Trade Union Act .

Significance and Implications for Platform Businesses

This decision by the Tokyo Labor Relations Commission is a significant development with considerable implications for gig economy platforms operating in Japan.

1. A Key Precedent: While an administrative decision (potentially subject to challenge in court), it represents one of the first and most detailed official judgments in Japan on the TUA status of platform-based service providers in the prominent food delivery sector. It sets a benchmark and provides a clear analytical framework that other platforms and labor authorities will likely reference.

2. Focus on Operational Control and Integration: The ruling underscores that the assessment of worker status under the TUA goes far beyond the contractual label. Platforms that exert significant control over how work is performed (through detailed guidelines, rating systems, disciplinary measures like suspension), deeply integrate providers into their core service delivery, and unilaterally set compensation terms are at higher risk of having those providers classified as TUA workers, even if the providers retain flexibility over working hours and location.

3. Potential for Collective Bargaining: The immediate consequence of TUA worker status is the right to organize and the obligation for the company (or companies, as found here) to engage in collective bargaining upon request from a qualified union. Platforms operating in Japan must now factor in the potential for unionization among their contractors and the associated duty to negotiate over terms and conditions.

4. Distinction from Broader Employee Status: It bears repeating that this decision specifically addresses status under the Trade Union Act. It does not automatically classify the riders as "employees" under the Labor Standards Act or other laws governing minimum wage, overtime pay, dismissal protection, etc. Establishing full employee status requires meeting a different, generally stricter, set of criteria focused more heavily on direct command relationships and time/place constraints. However, achieving TUA worker status is often seen as a potential stepping stone toward broader recognition of employment rights.

5. Alignment with Global Scrutiny: The Japanese Commission's substance-over-form, multi-factor analysis resonates with global trends. Jurisdictions in the US (like California with its ABC test, and evolving federal NLRB standards) and Europe are increasingly scrutinizing the classification of gig workers, often using similar tests focused on control, integration, and economic reality rather than just contractual designation. This ruling shows Japan is part of this international conversation.

6. Need for Platform Risk Assessment: Companies utilizing platform models in Japan, whether in delivery, ride-sharing, freelance work, or other sectors, should proactively assess their operational models in light of this decision. Key areas for review include:

* How much control is exercised over the manner in which services are performed (guidelines, scripts, required equipment)?

* How are performance standards monitored and enforced (ratings, suspensions, deactivations)?

* Who sets the price for the service, and can providers negotiate it?

* Are providers restricted from working for competing platforms (multi-homing)?

* Can providers genuinely use substitutes or delegate work?

* How essential and integrated are the providers to the platform's core business offering?

Addressing these questions can help platforms understand their potential exposure under the TUA and consider whether model adjustments might be necessary or prudent.

Conclusion

The Tokyo Labor Relations Commission's decision classifying food delivery riders as "workers" under the Trade Union Act marks a significant moment for Japan's gig economy. It demonstrates that flexibility in hours and location does not preclude worker status if the platform exercises substantial operational control and integrates providers deeply into its business model. While not equating these workers with traditional employees for all purposes, the ruling firmly establishes their right to organize and bargain collectively under Japanese law. Platform companies operating in Japan must now carefully consider the implications of this decision, evaluate the structure of their relationships with service providers, and prepare for the potential rise of collective bargaining in the platform sector.

- Perfecting Claim Assignments in Japan: Is the “Certified Date” or Actual Arrival Time Decisive for Priority?

- Director Liability in Japan: A Case Study Involving Attorney Directors and M&A

- Double Assignment of Claims in Japan: Who Wins and Why?

- デジタルプラットフォームとプラットフォームワーカーをめぐる状況(厚生労働省資料)

- プラットフォーム労働における労働条件改善に関するEU指令案 解説資料(厚生労働省)

- Labor Union Act – English Translation (japaneselawtranslation.go.jp)