Japan’s Algorithm-Change Antitrust Case: How Platforms Risk “Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position”

TL;DR

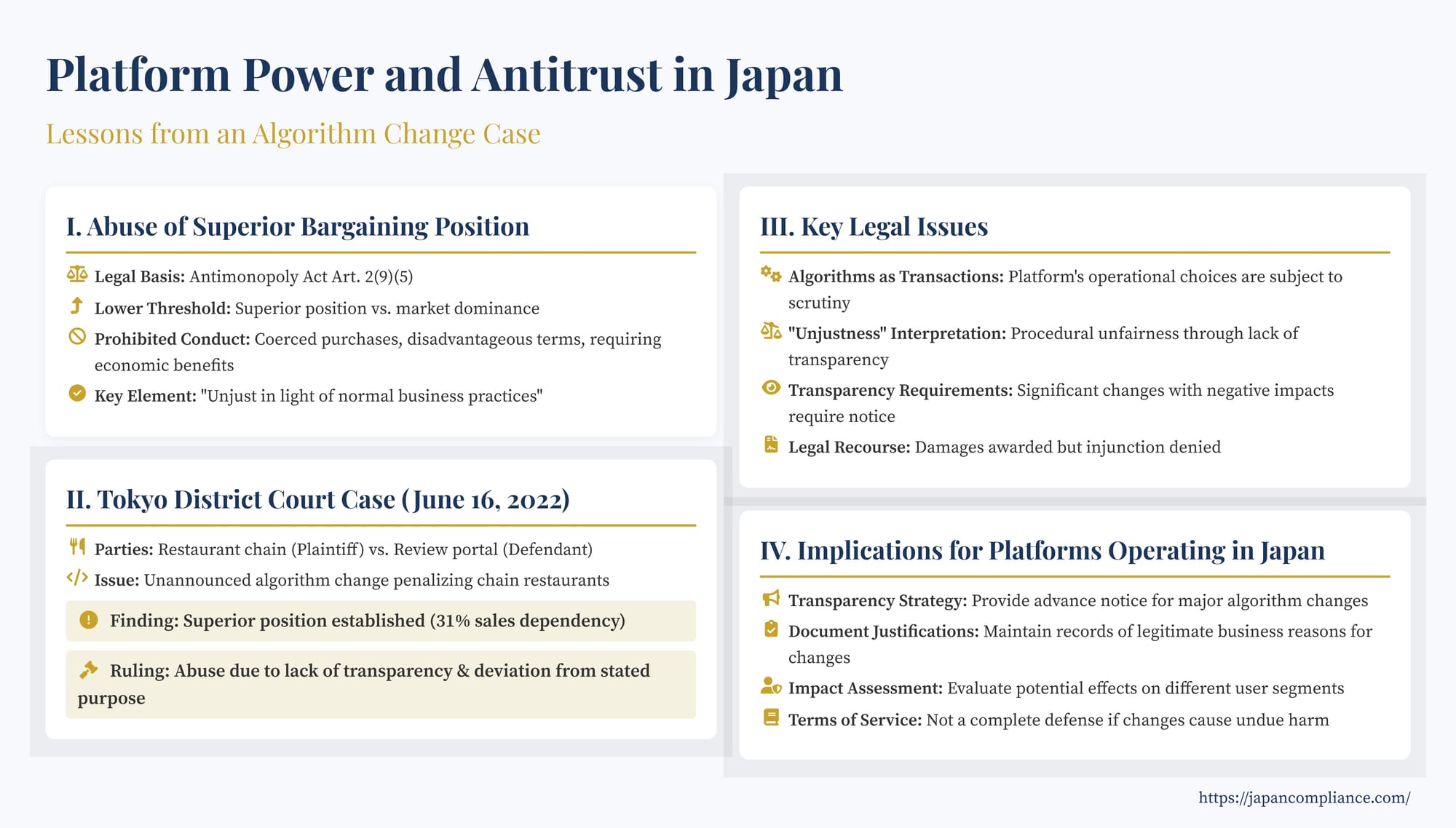

- Tokyo District Court (16 Jun 2022) found a restaurant-rating platform abused a Superior Bargaining Position by secretly tweaking its algorithm to penalise chains.

- Key factors: platform dependence (31 % of sales), no prior notice, deviation from stated anti-manipulation purpose.

- Damages awarded despite injunction denial—“unjust” implementation under Japan’s Antimonopoly Act.

- Platforms must assess impact, document justifications, and provide notice for major ranking changes to avoid AMA liability.

Table of Contents

- Understanding Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position (Yūetsuteki Chii no Ranyō)

- The Case: Restaurant Portal Algorithm Change (Tokyo District Court, June 16 2022)

- Key Legal Issues and Analysis

- Implications for US Businesses

- Conclusion

Digital platforms have become integral to the modern economy, connecting businesses with consumers and facilitating vast amounts of commerce. However, their growing influence raises significant competition law questions worldwide. How should antitrust regulators address the immense power wielded by dominant platforms? Japan offers a unique perspective through its Antimonopoly Act (AMA), particularly the prohibition against "Abuse of a Superior Bargaining Position" (優越的地位の濫用 - Yūetsuteki Chii no Ranyō). This provision allows the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) and courts to address conduct that might fall outside the scope of traditional monopolization or collusion frameworks seen in the US or EU.

A Tokyo District Court decision from June 16, 2022 (Reiwa 2 (Wa) No. 12735), provides a compelling example of how this doctrine applies in the digital age, finding that an unannounced algorithm change by a major online platform constituted an abuse of its superior position relative to a business user. This case offers valuable lessons for platforms operating in Japan and businesses reliant upon them.

Understanding Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position (Yūetsuteki Chii no Ranyō)

Before examining the case, it's essential to grasp the concept of Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position under the AMA. Codified in Article 2, Paragraph 9, Item 5, it prohibits an enterprise from unjustly, in light of normal business practices, engaging in certain types of conduct by taking advantage of its superior bargaining position over a counterparty. The specified conduct includes:

- Forcing the purchase of unrelated goods/services.

- Coercing the provision of economic benefits (money, services, etc.).

- Setting or changing transaction terms disadvantageously.

- Modifying or implementing transactions disadvantageously.

- Requesting actions detrimental to the counterparty's management.

Key elements distinguish this from other antitrust regimes:

- Superior Bargaining Position, Not Necessarily Dominance: The threshold is lower than market dominance required under EU Article 102 or US Sherman Act Section 2. A "superior bargaining position" exists if one party (A) finds it significantly difficult to maintain stable business operations should the other party (B) make it difficult or impossible to continue transacting with B. This often depends on factors like the degree of reliance on the transaction, the counterparty's market position, the ability to switch counterparties, and other concrete facts indicating dependence.

- Focus on Unfairness in Vertical Relationships: While traditional antitrust often focuses on horizontal collusion or monopolization harming market-wide competition, Yūetsuteki Chii no Ranyō directly addresses potentially exploitative or unfair conduct within a vertical buyer-seller or platform-user relationship.

- "Unjust in Light of Normal Business Practices": The conduct must be deemed unfair when compared to established, fair business customs (正常な商慣習 - seijō na shōkanshū). This introduces a degree of flexibility but also requires careful consideration of industry norms and reasonableness.

The JFTC has issued guidelines clarifying the application of this provision, including specific guidance for digital platforms, recognizing their potential to hold superior positions over business users reliant on their ecosystems.

The Case: Restaurant Portal Algorithm Change (Tokyo District Court, June 16, 2022)

This case involved a legal battle between a restaurant chain operator (Plaintiff) and the operator of a major restaurant review and booking portal (Defendant Platform).

The Facts:

- The Defendant Platform operated a highly influential portal ("Site A") listing virtually all restaurants nationwide, offering both free listings and paid memberships for enhanced features.

- Site A displayed user-generated ratings (評点 - hyōten) for restaurants, calculated via a proprietary algorithm. This algorithm considered factors like user scores and reviewer influence (based on dining history etc.) and heavily influenced restaurant search rankings on the site.

- The Defendant Platform stated its policy was to keep the algorithm confidential and periodically review it solely to prevent manipulation (e.g., fake reviews, artificial inflation of reviewer influence). No other reasons for changes were publicly communicated.

- On May 21, 2019, the Defendant Platform implemented a significant change to its rating algorithm ("the Change"). Critically, affected restaurants, including the Plaintiff, were not notified of this Change either before or after its implementation.

- The Plaintiff, operating a chain of yakiniku (Japanese BBQ) restaurants, experienced a noticeable drop in the ratings for its various locations following the Change.

- The Plaintiff alleged that the Change specifically incorporated a factor that penalized restaurants belonging to a chain (i.e., multiple outlets under the same operator) and argued this constituted either discriminatory treatment or an Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position under the AMA. The Plaintiff sought an injunction to stop the use of the modified algorithm and claimed damages for lost profits resulting from decreased visibility and customer traffic.

Establishing Superior Bargaining Position:

The court first determined that the Defendant Platform indeed held a superior bargaining position over the Plaintiff restaurant chain. The reasoning included:

- Significant Dependence: The Plaintiff derived an average of 31% of its sales through Site A, indicating substantial reliance.

- Difficulty Switching: The Plaintiff felt compelled to remain a paid member even after the detrimental Change, suggesting a lack of viable alternatives or high switching costs.

- Platform's Market Power: The court acknowledged the Defendant Platform's powerful standing within the Japanese restaurant portal market.

Finding of Abuse (Yūetsuteki Chii no Ranyō):

Having established the superior position, the court found that the algorithm change constituted an abuse:

- Disadvantageous Implementation: The court broadly interpreted the AMA provision prohibiting "implementing transactions... in a way disadvantageous to the counterparty." It held that displaying algorithmically generated ratings on a restaurant's page on Site A was part of "implementing the transaction" for paid members. The unannounced Change, which lowered the Plaintiff's ratings and subsequent traffic/sales, was therefore a disadvantageous implementation.

- "Unjust in Light of Normal Business Practices": This was the crucial finding. The court deemed the Change unjust primarily because:

- Lack of Transparency/Notice: The Defendant Platform failed to notify affected restaurants before making a change with significant negative consequences.

- Unforeseeability: The disadvantage imposed (lower ratings due to being part of a chain) was not something the Plaintiff could reasonably anticipate based on the Defendant Platform's prior communications, which only mentioned changes aimed at preventing manipulation.

- Deviation from Stated Purpose: The court implicitly found that the Change went beyond merely preventing manipulation and introduced a new, undisclosed factor (penalizing chains), deviating from the platform's own stated rationale for algorithm adjustments.

Injunction Denied, Damages Awarded:

- The court denied the Plaintiff's request for an injunction. It reasoned that the Plaintiff had not demonstrated a risk of "significant harm" (著しい損害 - ichijirushii songai) as required by AMA Article 24. The court felt the Change didn't immediately threaten the Plaintiff's business survival and suggested that if the platform were to disclose the change, consumers could simply adapt their choices, mitigating ongoing damage.

- However, the court acknowledged that the Plaintiff had suffered actual harm (lost profits) directly caused by the ratings drop resulting from the unjust algorithm change. It therefore awarded partial damages, recognizing the established causal link between the Defendant's abusive conduct and the Plaintiff's financial losses.

Key Legal Issues and Analysis

This judgment offers significant insights into how Japanese competition law grapples with platform power:

1. Algorithms as Part of the "Transaction":

The court's willingness to classify the display of algorithmically generated ratings as part of "implementing the transaction" is important. It signals that platforms' ongoing operational choices and the outputs of their systems, not just explicit contractual terms, can fall under the scrutiny of the Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position doctrine. This broad interpretation means platforms cannot easily claim that algorithm outputs are merely neutral background conditions separate from their dealings with business users.

2. The Meaning of "Unjust in Light of Normal Business Practices":

This case highlights that "unjustness" can arise from procedural unfairness, particularly a lack of transparency and predictability. While the substance of the algorithm change (penalizing chains) was likely a factor, the court heavily emphasized the manner in which it was implemented – unannounced and deviating from previously stated policies. This suggests that even if a platform has legitimate reasons for an algorithm change, implementing it abruptly and without notice, causing foreseeable harm to reliant business users, can render the action "unjust" under the AMA. It underscores the importance of legitimate business expectations in the platform-user relationship.

3. The Role of Transparency and Notification:

The lack of prior notification was central to the finding of abuse. This raises critical questions for platforms: What level of transparency is required? Does every minor algorithm tweak need disclosure? Probably not. However, changes that are likely to have a significant, potentially negative, impact on specific categories of business users (like penalizing chains in this case) appear to carry a higher burden regarding transparency under Japanese law. Failing to notify users in such circumstances significantly increases the risk of the change being deemed an "unjust" abuse. The platform's stated purpose for making changes also becomes relevant; deviating from that stated purpose without explanation or notice weakens the platform's position.

4. Platform Justifications:

As noted in commentary surrounding the case, the Defendant Platform's specific justification for penalizing chains was likely redacted from the public judgment. Potential justifications might include improving overall user experience (if data showed users preferred independent restaurants), combating specific manipulation tactics perceived as more common among chains, or promoting diversity in search results. Under an Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position analysis, such justifications would need to be weighed against the harm caused to the disadvantaged party and the fairness of the implementation process (including transparency). A lack of transparency makes it harder for a platform to convincingly argue its justification was reasonable and the action fair.

5. Global Context:

Japan's focus on Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position provides a different lens for platform regulation compared to the dominance-focused approaches of traditional EU/US antitrust law (though newer regulations like the EU's Digital Markets Act also address fairness issues). Yūetsuteki Chii no Ranyō allows intervention based on bargaining power imbalances and specific unfair practices, potentially offering a more flexible tool to address platform conduct that harms business users even if it doesn't rise to the level of market-wide monopolization.

Implications for US Businesses

This case holds important lessons for US companies interacting with the Japanese market, whether as platform operators or business users:

For Platforms Operating in Japan:

- Scope of AMA: Recognize that the Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position doctrine can apply even if your platform isn't traditionally "dominant" in the market. Focus on dependencies created in your relationships with Japanese business users.

- Algorithm Change Management: Implement processes to assess the potential impact of significant algorithm changes on different user segments. Changes likely to cause substantial disadvantage warrant careful consideration.

- Transparency Strategy: Develop a clear strategy regarding transparency for algorithm changes. While full disclosure is often impractical, providing advance notice for major changes that deviate from established ranking factors or introduce new penalties could mitigate AMA risks. Clearly articulating the purpose of changes and adhering to those stated purposes is crucial.

- Justification and Documentation: Ensure legitimate business justifications exist for significant algorithm changes and document the reasoning. Be prepared to explain why the change was necessary and proportionate.

- Terms of Service: While helpful, simply stating in terms of service that algorithms can change at any time may not be a complete defense if a specific change is implemented unfairly and without notice, causing undue harm.

For Businesses Using Japanese Platforms:

- Know Your Rights: If you rely heavily on a major Japanese platform and suffer significant, unforeseeable disadvantage due to unilateral actions like unannounced algorithm changes, you may have recourse under the AMA's Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position provisions.

- Document Everything: Keep records of your reliance on the platform (e.g., percentage of revenue derived), communications with the platform, and any negative impacts (e.g., drops in visibility, traffic, sales) following platform actions. This data is crucial for demonstrating harm and potential abuse.

Conclusion

The Tokyo District Court's decision in the restaurant portal case marks a significant application of Japan's Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position doctrine to the complex world of digital platform algorithms. It sends a clear message that platforms holding a position of significant influence over their business users cannot implement major, disadvantageous changes – particularly to core functions like ranking algorithms – with impunity and without transparency. The ruling underscores that under Japanese competition law, the fairness of the process, including predictability and adequate notification, is paramount in the platform-business user relationship. While the global landscape of platform regulation continues to evolve, this case highlights the unique considerations and potential liabilities platforms face under the specific framework of Japan's Antimonopoly Act. Both platforms entering the Japanese market and businesses utilizing them need to be acutely aware of these dynamics.

- Understanding Exclusionary Practices Under Japan’s Antimonopoly Act

- Playing a Leading Role? Japan’s Antitrust Surcharge Enhancements for Cartel Facilitators

- Japan Targets Mobile Ecosystems: Inside the Smartphone Software Competition Promotion Act

- JFTC Guidelines on Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position (2010, general) :contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}

- JFTC Guidelines on Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position by Digital Platforms (2019) :contentReference[oaicite:1]{index=1}

- JFTC Report “Algorithms/AI and Competition Policy” (2021) :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}