Piercing the Corporate Veil in Japan: A Doctrine of Substantive Liability, Not Direct Judgment Enforcement

The foundational principle of corporate law is that a company is a legal entity separate and distinct from its shareholders and directors, possessing its own rights and liabilities. However, courts in various jurisdictions, including Japan, have developed the doctrine of "disregard of corporate personality" (法人格否認 - hōjinkaku hinin), often known internationally as "piercing the corporate veil." This equitable doctrine allows courts to look beyond the corporate facade and hold individuals or affiliated companies liable for the corporation's obligations in specific circumstances, typically involving fraud or abuse of the corporate form.

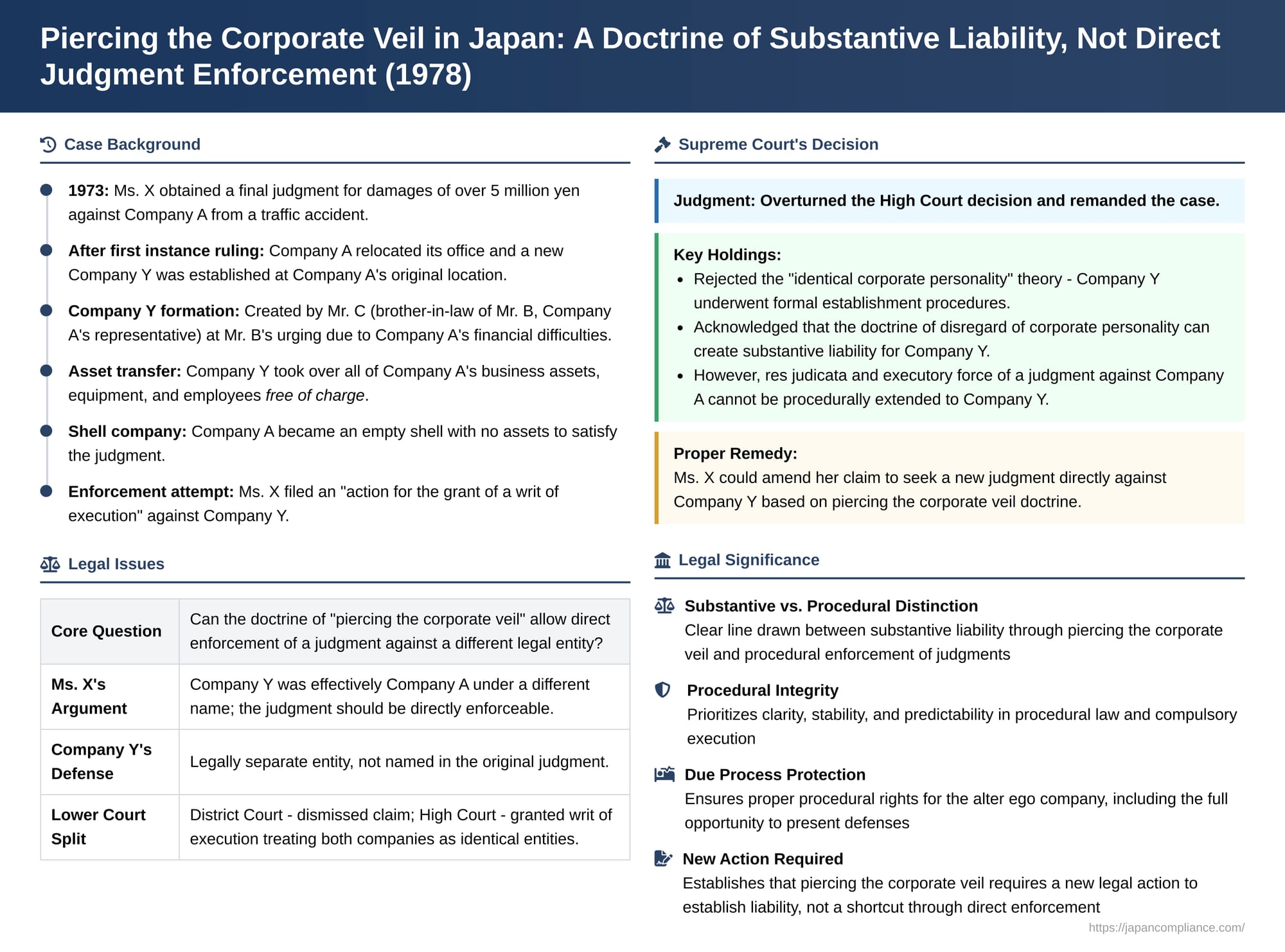

A critical question that arises is how this doctrine interacts with the enforcement of judgments. If a creditor obtains a judgment against one company (Company A), and another company (Company Y) is later found to be an alter ego or a vehicle established to evade Company A's liabilities, can the creditor directly enforce the judgment against Company A upon Company Y? A significant 1978 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan addressed this precise issue, clarifying that while the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality can establish substantive liability for the alter ego company, it does not permit the direct extension of the executory force of a judgment obtained against the original company.

Background of the Dispute

The plaintiff, Ms. X, had secured a final judgment in 1973 for damages amounting to over 5 million yen against Company A (a pig farming business, hereinafter "Company A") arising from a traffic accident.

Two years prior to this final judgment, and tellingly, just after the court of first instance had initially ruled in Ms. X's favor against Company A, significant changes occurred. Company A's registered head office was relocated to an adjacent district. Simultaneously, a new company, Company Y (using a strikingly similar name, "A Yōton Kabushiki Kaisha," hereinafter "Company Y"), was established at the original head office location of Company A.

The formation of Company Y was orchestrated under circumstances strongly suggesting an attempt to shield assets from Company A's creditors:

- Mr. C, the brother-in-law of Mr. B (the representative director of Company A), invested 10 million yen to establish Company Y and became its representative director. This was reportedly done at Mr. B's urging, as Mr. B sought financial assistance for Company A, which was facing financial difficulties and the prospect of a large damages award to Ms. X. Due to Company A's existing debts, Mr. C was reluctant to invest directly in it.

- Company Y then took over all of Company A's business assets—including pig farming facilities, equipment, vehicles, and all existing pigs—free of charge.

- Company Y also absorbed all of Company A's employees.

- Company Y commenced the same pig farming business using Company A's former premises and assets.

- As a result of these transfers, Company A was reduced to an empty shell, a mere nominal entity.

While Mr. B, the representative of Company A, was not formally a director of Company Y, the directorships of both companies showed some overlap and were largely composed of family members. Mr. C, Company Y's representative, had no prior experience in pig farming, and the actual management of Company Y was effectively in the hands of those who had previously managed Company A.

Facing an insolvent Company A, Ms. X sought to enforce her judgment. She filed an "action for the grant of a writ of execution" (執行文付与の訴え - shikkōbun fuyo no uttae) against Company Y, arguing that the judgment against Company A should be directly enforceable against Company Y.

The Kyoto District Court (court of first instance) dismissed Ms. X's claim. While it acknowledged that Company Y's establishment was likely intended to help Company A evade its debts and could be considered an abuse of corporate personality (meaning Company Y could not, in substance, claim to be entirely separate from Company A for liability purposes), it held that the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality does not apply in the realm of procedural law, such as the issuance of a writ of execution.

The Osaka High Court (appellate court), however, reversed this decision. It granted Ms. X's request, reasoning that Company A and Company Y were, in reality, the same corporate personality merely appearing under dual registrations. The High Court concluded that a judgment against the "old" company could therefore be enforced against the "new" company and that the issue of their identical personality was appropriately determined within the action for the grant of a writ of execution. Company Y appealed this ruling to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court of Japan overturned the Osaka High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Supreme Court's judgment drew a clear line between the substantive effects of the disregard of corporate personality doctrine and its procedural application in judgment enforcement:

- Rejection of the "Identical Corporate Personality" Theory:

The Court first addressed the High Court's finding that Company A and Company Y were "entirely the same corporate personality." It stated that since Company Y had undergone the formal procedures for establishment and was registered as a legal entity separate from Company A, it could not be immediately concluded that they shared the same corporate identity based solely on the described factual interconnections. Such a conclusion, the Court reasoned, would be difficult to reconcile with provisions of the Commercial Code (now the Companies Act) which stipulate that the invalidity of a company's establishment can only be asserted through a specific lawsuit for nullification of formation (under then Article 428 of the Commercial Code; now equivalent to Article 828(1)(i) of the Companies Act). It also cited the need for "legal stability" as a reason to reject this approach. - Doctrine of Disregard of Corporate Personality Applicable for Substantive Claims:

The Supreme Court then acknowledged the potential applicability of the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality in a substantive sense. It stated that if Company Y's establishment was indeed carried out with the intent to enable Company A to evade payment of its debts, and if this conduct amounts to an abuse of the corporate personality, then it would be appropriate to conclude that Ms. X could, by invoking the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality, assert her damages claim (which was the basis of her judgment against Company A) directly against Company Y. This means Ms. X could potentially file a new lawsuit against Company Y, seeking payment of the same debt. - Non-Extension of Res Judicata and Executory Force in Procedural Law:

This was the crucial part of the ruling. The Supreme Court held that even if the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality applies substantively (allowing Ms. X to sue Company Y anew), in the context of litigation procedure and compulsory execution procedure—which prioritize clarity and stability for the authoritative determination and swift and certain realization of rights—the res judicata (binding effect of the judgment) and the executory force (enforceability) of the judgment against Company A cannot be extended to Company Y.

In reaching this conclusion, the Supreme Court explicitly referenced its own 1969 First Petty Bench decision (Showa 44.2.27, Minshu Vol. 23, No. 2, p. 511), which had previously indicated (albeit in obiter dictum, or a non-binding judicial comment) that the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality should not lead to the extension of a judgment's effects to a separate entity not named in the original judgment. - Remand for Potential Amendment of Claim:

While the Supreme Court denied Ms. X's attempt to directly enforce the judgment against Company A upon Company Y, it did not leave her without a potential remedy. Recognizing the strong factual basis suggesting an abuse of corporate personality, the Court remanded the case to the Osaka High Court. It noted that, based on the established facts, Ms. X might have grounds to amend her claim during the remanded appellate proceedings to seek a new judgment for damages directly against Company Y, based on the same underlying tort that led to the judgment against Company A. This would allow the courts to adjudicate Company Y's liability under the disregard doctrine in a procedurally proper manner.

Significance and Analysis of the Decision

This 1978 Supreme Court decision is a cornerstone in Japanese law concerning the procedural implications of the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality.

- Clear Line Drawn: The judgment firmly establishes that while piercing the corporate veil can create substantive liability for an alter ego company (making it responsible for the debts of another), it cannot be used as a procedural shortcut to directly enforce a judgment obtained against the original company upon the alter ego company without a new, separate adjudication against that alter ego.

- Procedural Integrity Prioritized: The Court's rationale emphasized the importance of maintaining clarity, stability, and predictability in procedural law, especially in the context of compulsory execution. Allowing the executory force of a judgment to be extended to a company not named in the original title of obligation, based on a complex, fact-intensive inquiry into whether the corporate veil should be pierced, would introduce significant uncertainty and potential for delay into the enforcement process. Such a substantive determination, the Court implied, is best made in a full adjudicative proceeding against the company whose veil is sought to be pierced.

- Protection of the "New" Company's Due Process Rights: By requiring a new lawsuit (or an appropriately amended claim) against Company Y, the decision ensures that Company Y receives full procedural due process, including the opportunity to present its own defenses against the claim that it should be held liable for Company A's debts. This is a fundamental aspect of procedural fairness.

- Rejection of "De Facto Identity" for Enforcement Purposes: The Supreme Court explicitly rejected the High Court's approach of treating the two separately registered companies as a "single corporate personality" for the purpose of extending judgment enforceability. This reaffirms the formal separation of legal entities unless specific legal grounds (like a formal merger or a successful nullification of formation) dictate otherwise.

- The 1969 Precedent Solidified: The 1978 decision builds upon and solidifies the stance indicated in the 1969 Supreme Court case, making it clear that the disregard of corporate personality doctrine operates primarily within substantive law to establish liability, rather than within procedural law to expand the direct effects of an existing judgment to non-parties.

- Academic Debate and Basis of the Doctrine: The Supreme Court has never explicitly pinpointed a single statutory basis for the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality, though the principle of "abuse of rights" (Civil Code, Article 1, Paragraph 3) is considered a key foundation. The commentary also delves into the academic debate about whether and how the doctrine should apply in procedural contexts. The prevailing view, supported by this judgment, is against direct procedural extension.

- Alternative Avenues for Relief: While denying direct enforcement of the existing judgment, the Supreme Court's remand offered Ms. X a path to pursue Company Y through a new substantive claim.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1978 ruling in this case provides a critical clarification on the limits of the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality within the Japanese legal system. It establishes that piercing the corporate veil is a tool to assign substantive liability to an otherwise separate entity that has abused the corporate form, typically requiring a new legal action to establish that liability. It is not, however, a mechanism for summarily extending the executory force of a judgment obtained against one corporation to another, even if they are closely related or one was formed to evade the debts of the other. This decision underscores the Japanese legal system's commitment to procedural regularity and the due process rights of all named parties, even in the face of attempts to misuse the corporate structure. Creditors facing such situations must typically initiate fresh legal proceedings against the entity whose veil they seek to pierce.